Introduction

Chester Cathedral from the south-east. Photograph by Stephen Hamilton. Source: Wikipedia

First, my sincere thanks to Katie Crowther Chester Green Badge tourist guide, who initiated me into the multi-layered and complex history of the cathedral and its environs. On holidays in the past I have experienced horrible tour guides, primed to stuff visitors to the eyebrows with indigestibly voluminous facts and figures, until the will to live id vanishing fast, sanity is being eroded by the nanosecond, and absolutely nothing sticks. Katie, by contrast, imparted exactly the right amount of information to make sense of how the building had evolved and how it had functioned in the course of its daily existence, pointed out unmissable features from every period, talked through key figures in the cathedral’s distant and more recent past, and answered all my questions., It was not a wall of sound. It was a relaxed stroll, not a route march, and I came away feeling bright, alert and informed, rather than resentfully crushed and exhausted 🙂 Needless to say, any opinions and any errors below are my own, and nothing to do with Katie’s excellent narrative.

It is quite impossible to do justice to Chester Cathedral in a single blog post, so I have had to cherry-pick just a handful of features. There is so much to see, and it is a place that rewards repeat visits.

Although the title of the post refers to this being my first visit, I had in fact visited the cathedral many years ago, but I had no clear recollection of the appearance of the interior which is infinitely more impressive then I remembered. The red sandstone, beautifully carved and finely finished, gives it a warmth and personality that I had forgotten, and there were features like the the utterly superb quire and misericords (mercy seats) and the consistory court that were so surprisingly original and unique that I blush for the fact that I had failed to appreciate it all on my previous visit.

We arrived at the cathedral on Friday 25th February, a bright and sunny day that filled the place with light. I had a head stuffed with a complete tangle of questions. Who was the cathedral dedicated to? Who was St Werburgh and why is she featured so strongly in the cathedral’s iconography? I remember being surprised some time ago that she was female. Her name is clearly Anglo-Saxon, so how does that fit in to a Christian context? The cathedral was previously an abbey, and most monastic houses were dissolved by Henry VIII, so how did it survive to become the most important ecclesiastical establishment in Chester? And, in passing, why on earth is the south transept so ridiculously enormous? Katie explained all.

St Werburgh

7th Century Britain. Source: Wikipedia

The story starts not in Cheshire, but Mercia. Mercia no longer exists, but what we call Cheshire today is a small northern part of the vast Mercian hegemony, which peaked during the 8th Century, when it covered a huge portion of England south of the line of the Mersey. Christianity had not replaced older religious beliefs at this time, but it was making inroads. Pope Gregory the Great had sent a mission to convert England in the 6th century, and his envoy Augustine was given permission by the King of Kent, whose wife Bertha was Christian, to establish himself in Canterbury and to preach the Christian message. The message was slowly disseminated throughout England, and the monastic tradition began to gather real momentum during the 7th century.

Werburgh, or Werberga, was a royal princess, born in Stone in today’s Staffordshire in the mid 7th century at around 650. Her parents were King Wulfhere and Queen Ermenilda, herself daughter of King Eorcenberht of Kent, where Augustine had first established himself. Werburgh’s maternal aunt was Etheldreda, Abbess of the Abbey of Ely. Options were limited for an aristocratic woman in the 7th century, and rather than chosing marriage Werburgh opted for the conventual life, following in her aunt’s footsteps and eventually rising to the position of Abbess of all the nunneries in Mercia.

Lovely pilgrim badge showing the geese of St Werburgh, probably bought in the 14th century by a pilgrim to the abbey. Source: British Museum

Saints, as part of their job description, perform miracles, evidence of being touched by God. Werburgh’s main miracle is somewhat unusual. As well as the usual miracles “to alleviate sickness, trouble, pain or personal problems” (Nick Fry 2009), her main claim to miraculous fame was the episode with the goose. When Werburgh heard that geese were attacking attacking the abbey’s fields, she asked a servant to round them up and secure them. He was unable to resist temptation, and cooked and consumed one of them. When Werburgh returned and set about releasing the geese, its companions asked for their missing friend to be returned to them. Touched by their pleas, she gathered up the carcass and feathers of the eaten goose, and brought the bird back to life. This story may incorporate the reality of flocks of migratory geese devastating crops, with placatory sacrifices made to prevent such devastation. These, when combined with ideas of resurrection, were all folded into the interface between the still partially pagan community and the Christian church, formalized in communal secular rites of gleaning (leftover crops collected by the poor) and the Christian celebration of the harvest (in which fruit, vegetables and grain crops were donated to the poor), which Thomas Pickles refers to as “the moral economy.”

Werburgh died on February 3rd in 706 and was buried at Hanbury in Staffordshire. This was not, however, her final resting place. Viking incursions in the 9th Century led to the decision to move Werburgh to greater safety. When her tomb was opened, she was found to be perfectly preserved, absolute confirmation that she was indeed a saint. Werburgh was brought to Chester, a fortified and much more secure urban location than Hanbury. It is thought that there was a wooden church dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul founded here by Wulfhere, which would have housed her remains, and over which the abbey was later built. When the abbey was erected, she was rehoused within its walls and remained safe until Henry VIII’s suppression of the monastic houses, when her shrine was destroyed and her remains lost. The remnants of her shrine were reconstructed in the 19th Century, and remain today within the cathedral, but Werburgh’s remains were never recovered. Werburgh continues in her role as the patron saint of Chester, which is one of a handful of English cities to have a female patron saint (including Ely, whose patron saint is Werburgh’s aunt Etheldreda).

Hugh “Lupus” d’Avranches and the Benedictine Abbey

Coat of arms of Hugh d’Avranche. Source: Wikipedia

The history of any ecclesiastical establishment is greatly influenced by its patrons and by the aristocracy that owned the land on which it was built. Early pre-Norman monasteries were dependent upon initial royal patronage and ongoing interest.

After the Norman conquest under William in 1066, Norman aristocrats were put into positions of power, particularly along the Welsh borders, and they too began to found monastic houses. In Chester, which had given William considerable trouble in the 1070, William installed his nephew Hugh d’Avranches (1047-1101), as Earl of Chester, an immensely powerful position with powers second only to the king. He was known as Hugh Lupus (Hugh the Wolf) in earlier life, and later on (and much less flatteringly) Hugh the Fat. His first major investment was the building of Chester Castle. Having already founded two Benedictine monasteries in Normandy, in 1092 Hugh set about creating a new abbey in Chester, inviting the great theologian and philosopher Anselm (Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109) to advise him. The new Abbey of Saint Werburgh provided a new home for the saint, whose remains had attracted pilgrims from the moment of her death, and gave Hugh Lupus the hope not only that monastic prayers would ensure his salvation, but that pilgrims would help to support the abbey’s upkeep. In tones of some austerity and disapproval, John Hicklin summarizes his final years:

Hugh Lupus, following the example of most of his predecessors, lived a life of the wildest luxury and rapine. At length, falling sick from the consequence of his excesses, and age and disease coming on, the old hardened soldier was struck with remorse; and—an expiation common enough in those days—the great Hugh Lupus took the cowl, retired in the last state of disease into the monastery, and in three days was no more.

Plan of Chester Cathedral, showing how the layout is arranged around the abbey cloister, and providing an idea of how the building developed from the Norman period onwards. Click to expand, but also have a look at the source page, where the numbers are tied in to a key. Source: Wikipedia

An abbey, headed by an abbot or abbess and occupied by monks or nuns, is a monastic establishment, incorporating a church, chapels, administrative and domestic buildings, all arranged around a covered walkway that encloses a square garth, or garden. This walkway and garth, the cloister, was the focal point of British Benedictine and St Benedict-inspired monasteries. Chester’s abbey gave its character to the subsequent cathedral, with the abbey church forming one side of a four-sided architectural complex that surrounded a square cloister and “garth” or garden. The early abbey church was built along traditional lines, in the form of a cross. The long part of the cross was the nave, where the lay brothers (and later the general public) sat. This terminated at a stone screen (now a 19th century wooden screen), on the other side of which was the crossing, the section immediately under the tower. On either side of the crossing were the two short arms of the cross, called transepts. Beyond was the chancel, the private area where the monks performed their liturgies. As time went on, this basic plan became more elaborate as suggested on the above multi-period plan.

Interestingly, the abbey’s plan is, like Tintern in south Wales, flipped, counter to the Benedictine plan. In an ideal world the abbey church was built to the north of the cloister, putting the administrative and domestic buildings of the monastery around the cloister facing south, into the sun and warmth, the tall church building providing some shelter from the wind and rain. At Chester, however, the church was built to the south, and the other cloister buildings to the north. I can’t see any reason why this should be so, but sometimes the practicalities of sourcing water or building drainage caused this type of inversion where no topographical reason was obvious. The conventional arrangement of the abbey church has been retained, with an east-west axis in which the nave at the west end.

Although the Gothic style, first introduced into the monastery in the 13th century dominates today, early Norman Romanesque features are found at various points throughout the Cathedral. The most substantial and most arresting can be seen in the north transept, a great chunk of wall and arches thought to incorporate earlier Roman building materials. The Norman abbey church’s floorplan was big. Built in the shape of a cross, the long section, the nave, is thought to have been the size that it is today. The walls were shorter in height than the current cathedral, probably little more than half the height, and the east end was probably apsidal (semi-circular). The north transept (the left arm of the cross) sits on the original footprint of Hugh’s abbey church and retains some of its Romanesque features, with the rounded rather than pointed arches, with a row of small arched arcades perched on top of the great arch, representing the top level of the Norman abbey. The little row of arches may be Roman in origins. At the west end of the nave, the baptistry also features some superb Romanesque arches. The present day refectory dates mainly to the late 13 or early 14th century, but the arch leading into it from the cloister is Norman, its arch featuring scalloped shaping.

I thought I should say, before proceeding, that when I went back to take photographs on another day, the nave was filled with a purple light, and there was a raised platform, presumably for some upcoming event. Apologies, therefore, for the slightly surreal purple lighting in one or two of the shots that follow.

The Gothic Abbey

Although the Norman abbey defined the layout of the cathedral complex, it grew upwards and outwards as new demands were made of it and new abbots (and restorers) wanted to put their own stamp on it. The abbots and patrons of Chester, confronted with new abbeys being built all over England and Wales in the newly fashionable Gothic style with its soaring, upwardly mobile character, must have looked at their short walls and Norman curves and found them very dated. Major programmes of modernization began in the 12th Century and carried on throughout the abbey’s life until the late 1530s, not in a smooth programme of architectural revision, but in fits and starts as energy and funds permitted. One of the earliest of these transformations was the arch and window that accompanied the day stairs (leading from the former monks’ dormitory) in the east walkway, which are probably 12th century and are decorative but bold and unfussy. In 1282 the abbey remarkably introduced running water, which was piped from Christleton, two miles away.

Although the Norman abbey defined the layout of the cathedral complex, it grew upwards and outwards as new demands were made of it and new abbots (and restorers) wanted to put their own stamp on it. The abbots and patrons of Chester, confronted with new abbeys being built all over England and Wales in the newly fashionable Gothic style with its soaring, upwardly mobile character, must have looked at their short walls and Norman curves and found them very dated. Major programmes of modernization began in the 12th Century and carried on throughout the abbey’s life until the late 1530s, not in a smooth programme of architectural revision, but in fits and starts as energy and funds permitted. One of the earliest of these transformations was the arch and window that accompanied the day stairs (leading from the former monks’ dormitory) in the east walkway, which are probably 12th century and are decorative but bold and unfussy. In 1282 the abbey remarkably introduced running water, which was piped from Christleton, two miles away.

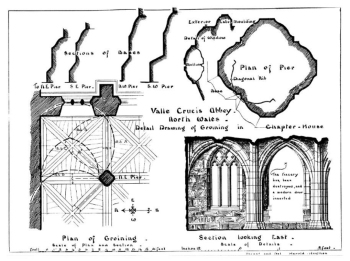

The mid 13 century remodelling of the important chapter house, where the monks met daily to discuss their work, address disciplinary matters and to hear a reading of a chapter from the Rule of St Benedict, included an impressive rib-vaulted roof, each vault slender and elegant. The vestibule, the approach to the chapter house, has a lower and less elegant still very impressive stone rib-vaulted ceiling as does the neighbouring slype (a passageway, which acted as a meeting place for the monks, sometimes referred to as a parlour).

From the earliest history of the abbey, those who were important to the abbey were buried there. An example is Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester, descendant of Hugh Lupus, and the builder of Beeston Castle. He died at Wallingford on 26 October 1232. According to one of his biographers, Iain Soden, Ranulf’s remains were divided between different places. His viscera were buried at Wallingford Castle, and his heart was taken to and buried at the abbey he had founded, Dieulacres, near Leek in Staffordshire. The remainder was carried to St Werburgh’s. Today this seems bizarre, but it was not at all unusual in the 13th century. (See my post about Ranulf here). The abbots of the abbey had the right to be buried at the site, and some of them were buried under the arches along the wall shared between the cloister and the church. This cloister was used for reading and writing, and it must have been unnerving for the monks to be watched over in their work by the former abbots.

The Lady Chapel was one of the first major additions to be completed during the abbey’s reinvention of itself, completed in the late 13th century, providing a new eastern extension of the south aisle. The “Lady” refers to the Virgin Mary, for whom a Mass was dedicated daily. George Gilbert Scott had a hand in its 19th century modernization, but the colours date to a sympathetic 1969 restoration of the chapel and are designed to replicate the types of colours that would have been used in in the medieval period. One of the surviving ceiling bosses is an usual and terrific scene showing the murder of Thomas Becket. Henry VIII ordered most of the scenes showing this event to be destroyed, making it a very rare survivor. All of these roof bosses, showing some similarly fascinating scenes, are well worth taking the time to appreciate.

The Lady Chapel was one of the first major additions to be completed during the abbey’s reinvention of itself, completed in the late 13th century, providing a new eastern extension of the south aisle. The “Lady” refers to the Virgin Mary, for whom a Mass was dedicated daily. George Gilbert Scott had a hand in its 19th century modernization, but the colours date to a sympathetic 1969 restoration of the chapel and are designed to replicate the types of colours that would have been used in in the medieval period. One of the surviving ceiling bosses is an usual and terrific scene showing the murder of Thomas Becket. Henry VIII ordered most of the scenes showing this event to be destroyed, making it a very rare survivor. All of these roof bosses, showing some similarly fascinating scenes, are well worth taking the time to appreciate.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the Gothic abbey is the quire area at the east end of the abbey church, where the monks delivered their liturgies, their songs and delivered their prayers, the opus dei (God’s work) laid down by St Benedict in his monastery in Monte Cassino, Italy, in the 6th century, which were performed seven times during the day and once at night. The Rule of St Benedict century states clearly that the opus dei should be delivered standing, which was a challenge for the elderly or otherwise impaired.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the Gothic abbey is the quire area at the east end of the abbey church, where the monks delivered their liturgies, their songs and delivered their prayers, the opus dei (God’s work) laid down by St Benedict in his monastery in Monte Cassino, Italy, in the 6th century, which were performed seven times during the day and once at night. The Rule of St Benedict century states clearly that the opus dei should be delivered standing, which was a challenge for the elderly or otherwise impaired.

From the 12th century onwards a small ledge began to be added to cathedral quires, providing support for the monks, particularly valuable for the elderly or infirm. Not a chair, more a prop to rest on, the misericords were the perfect opportunity to add decorative flourishes, and those at Chester are particularly splendid featuring scenes from a number of sources. They were constructed in around 1380, probably by the craftsmen who were responsible for the quire stalls in Lincoln Cathedral. It is worth taking some time to explore them. The elephant with horse’s hooves and a castle on his back is a particularly well known favourite, but all of them have massive charm and merit. If you are interested in the quire sculptures, a leaflet in the gift shop has an amazingly useful site plan of the quire, showing where to find each of the most interest corbels, misericords and bench ends.

The enormous south transept of the church, complete with side aisles, was a mid 14th century extension of the original south transept. Originally the south and north transepts, the short arms of the cross, will have mirrored one another. The extension was built to incorporate four new chapels for ordained monks to practise masses for the souls of the dead. In the mid-14th century, the time of the Black Death and subsequent phases of plague, the subjects of death and the reception of the dead were very much on the minds of all people.

Another feature of the abbey that survives today is the refectory, where the monks gathered to eat, most of which dates to the late thirteenth or early 14th century. One of my favourite details in the cathedral is the magnificent pulpit, built into the wall in stone, and reached via a stone staircase fronted by a row of five arches and itself framed by a pair of arches. The arches, although clearly gothic in inspiration, also appear to echo the scalloping of the Norman archway that opens into the refectory from the cloister. Meals were eaten in silence but, much like Cuban cigar factories, the silence was alleviated by readings. Religious texts and hagiographies (biographies of saints) were favourite subjects. The roof dates to 1939, and should not be missed.

As with the rest of Europe, the 14th century was scarred by successive plagues, the city was in crisis, labour was difficult to secure, the economy was under enormous strain. There was a hiatus in work in the abbey between 1360 and 1490.

Chester Cathedral garth. Photograph by Jeff Buck. Source: Geograph.

The garth, which would have been used for growing medicinal plants and herbs, is framed by a stone arcade, that today is sheltered by much later glass, about which more below. The cloister, its rib-vaulted arcade, with ornamental bosses where the ribs meet, and its arcade are very fine indeed, and although built first in the late 11th century, it was modified several times over the centuries, including the 19th and early 20th centuries. In spite of the different styles and ideas, it still manages to provide a sense of peace and orderliness. All the walkways were used for processional purposes, but each of the walkways could be used for different activities. In the north walkway, the lavatorium was located, a water trough in which the monks washed their hands before entering the refectory to eat.

In this cloister walkway, between the columns on the left, there were desks called carrels where the monks wrote and copied from other texts. A modern version has been placed there as an example. The arches on the right mark the burial places of former abbots.

During the medieval period, the role of literature became important in monastic establishments. The copying of books, both religious and historical, to build libraries and to disseminate knowledge, was an important part of many abbatial activities, carried out in the south walkways of the cloister, between its pillars, at desks called carrels. It is thought that the Chester “mystery plays” (dramatizations of episodes from either Old or New Testament) were written here and enacted by the monks up until the 14th century, when the Chester Guilds, of which 23 survive, took over, each performing a different play in the streets of Chester. The Ironmongers Guild performed The Crucifixion, for example, whilst the Guild of Grocers, Bakers and Millers performed The Last Supper. Opposite the carrels are arched recesses, which once housed tombs.

There are two pieces of glass thought to be original are fragments, tiny details. One shows a resurrected figure on Judgement Day, which is quite frankly the stuff of nightmares, and the other a man, crowned and bearded with a halo. The light was too dim for me to even make the attempt to photograph, so the two below are by Jeff Buck, from the Geograph website.

Medieval glass fragments incorporated into a modern design with plain glass. Photograph by Jeff Buck. Source: Geograph

Originally the abbey was supposed to have two big towers at the west front, in the style of Notre Dame in Paris or Kölner Dom in Cologne, but the early stump of the southwest tower, started at around 1508, was blocked off. It is interesting that ambitious construction was carrying on so late. Not only was the wealth to do this available, but there appears to have been no sense, at least at Chester, that the monastic system was under any threat, a threat that became a reality only 30 years later. The consistory court (see later) sits under the proposed site of the southwest tower and the baptistry under the northwest.

The abbey occupied 6 hectares of the town’s land, and was enclosed by walls with access controlled by gatehouses. This was a source of ongoing dispute between the abbey and the town, and as late as 1480 seems to have resulted in something of a brawl between monks and tradesmen. Greene comments that “the wall failed to prevent the monks from going out into the town to frequent taverns and consort with prostitutes,” behaviour that would not have endeared the monks to either the Church or to the townspeople.

The original monastic structure may have been quite neatly planned, but its growth over the centuries was clearly organic, responding to specific needs and ambitions, and even today continues to be modified as restoration and conservation require ongoing modifications.

Henry VIII’s new England and the founding of the Cathedral

What children of my generation all knew about Henry VIII was that his physical appearance was quite unmistakeable, and that he chopped off the heads of his wives. I am sure that our teachers tried to stuff us full of more relevant information, such as the importance of Henry’s decision to establish the Church of England, but rolling heads have a way of grabbing the attention in ways that ecclesiastical reform does not. I confess that the chopped heads still horrify me, but history turns its attention to the consequences of one particular beheading, that of Catherine of Aragon, who failed to deliver an heir to the crown. Henry wanted to divorce her but was denied permission by the Pope. In order to legalize his marriage to Anne Boleyn, he pushed through the Act of Supremacy, putting himself and his heirs at the head of the Church of England. Looking back at the earlier legacy of Henry I, whose only male heir had drowned, plunging the country into civil war on the king’s death, it was perfectly clear to kings that a legitimate male heir was essential for succession. Elizabeth I proved them wrong, but the legacy of the civil war between Henry I’s chosen successor, his daughter Matilda (often referred to as the Empress Maud), and Henry’s nephew Stephen, who took the throne on Henry’s death, would not have encouraged anyone to have high hopes of a stable country under parentally-sponsored female succession.

What children of my generation all knew about Henry VIII was that his physical appearance was quite unmistakeable, and that he chopped off the heads of his wives. I am sure that our teachers tried to stuff us full of more relevant information, such as the importance of Henry’s decision to establish the Church of England, but rolling heads have a way of grabbing the attention in ways that ecclesiastical reform does not. I confess that the chopped heads still horrify me, but history turns its attention to the consequences of one particular beheading, that of Catherine of Aragon, who failed to deliver an heir to the crown. Henry wanted to divorce her but was denied permission by the Pope. In order to legalize his marriage to Anne Boleyn, he pushed through the Act of Supremacy, putting himself and his heirs at the head of the Church of England. Looking back at the earlier legacy of Henry I, whose only male heir had drowned, plunging the country into civil war on the king’s death, it was perfectly clear to kings that a legitimate male heir was essential for succession. Elizabeth I proved them wrong, but the legacy of the civil war between Henry I’s chosen successor, his daughter Matilda (often referred to as the Empress Maud), and Henry’s nephew Stephen, who took the throne on Henry’s death, would not have encouraged anyone to have high hopes of a stable country under parentally-sponsored female succession.

Valle Crucis Abbey near Llangollen, founded in 1201, was dissolved in 1536 and thoroughly pillaged by Henry VIII, as well as being robbed for building stone by local people, and is now a ruin. This postcard shows it in 1905.

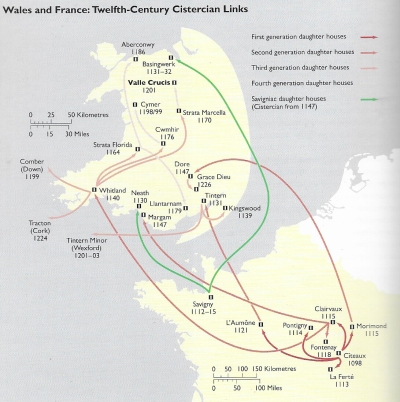

Henry VIII, now freed from Papal obligations, took the opportunity to “suppress,” or eliminate the monasteries. He saw them on the one hand as a disruptive legacy of the Papal regime, potentially undermining his new order, and on the other as a source of much-needed wealth. Some abbeys were merely pillaged for their leaded roofs, their valuable fittings and their treasures before everything else was auctioned off. Some were converted into parish churches, and still others were gifted to Henry’s followers and became elaborate homes. Other abbeys were less fortunate, and were razed to the ground. Chester Abbey experienced none of these humilities, being one of the rare ecclesiastical survivals of Henry VIII’s rampage of pillage and, in some cases, persecution.

As part of Henry’s reorganization of his lands, central England was divided into new regions. Whereas formerly Chester had been part of the enormous diocese of Lichfield (a diocese being an ecclesiastical unit, including parishes, over which a bishop had authority), Chester became a diocese in its own right, and it needed a cathedral of its own with a bishop at its helm. The former abbey was the perfect choice for fulfilling the role of an icon of Henry’s Church of England, stamping out the old and ushering in the new with the same sweeping wave of the royal hand in 1541. It became the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary

Chester Cathedral in 1656. Source: British History Online

The post-monastic cathedral in the later 16th century to the beginning of the 19th century is worthy of more than a small section on a single post. Chester Cathedral is so big and there is so much to see that it is difficult to pick out just a couple of features to talk about, but here are some that seem important to its role and its development. Interestingly, most of the cathedral’s footprint belongs to the abbey, and only a few extensions were made. That surprised me, but it is possible that an abbey that was home to an entire community of monks was more than enough for a non-residential cathedral.

The only Consistory Court to have survived history in Britain is now at the west end of the nave, a truly remarkable thing. It was originally built in the late 16th century, and located in the Lady Chapel. It was moved to the end of the nave in 1636, losing part of the canopy over the main chair in order to fit it in. Although tiny by modern court standards, there is something about it that remains seriously intimidating. The diocese had a significant role in legal issues, not merely wills and probate as one might expect, but also dealt with libel, witchcraft and heresy. They were also responsible for fining those who failed to attend church. It was a time-consuming role, and the chancellor was supported by to clerks, who flanked him, and an apparitor who sat in the seat raised at the corner to oversee the paperwork on the table below.

The only Consistory Court to have survived history in Britain is now at the west end of the nave, a truly remarkable thing. It was originally built in the late 16th century, and located in the Lady Chapel. It was moved to the end of the nave in 1636, losing part of the canopy over the main chair in order to fit it in. Although tiny by modern court standards, there is something about it that remains seriously intimidating. The diocese had a significant role in legal issues, not merely wills and probate as one might expect, but also dealt with libel, witchcraft and heresy. They were also responsible for fining those who failed to attend church. It was a time-consuming role, and the chancellor was supported by to clerks, who flanked him, and an apparitor who sat in the seat raised at the corner to oversee the paperwork on the table below.

A splendid memorial dating to 1602 is still in situ between the south transept and the crossing, brightly coloured and completely engaging. It depicts Thomas Greene, Sheriff of Chester in 1551 and mayor in 1569, with both of his wives, both of whom he outlived. All of their hands were originally clasped before them in prayer, but during the Civil War in the middle of the 17th century, the hands were chopped off because they were considered to be popish, and it is something of a miracle that the rest of the memorial survived.

A splendid memorial dating to 1602 is still in situ between the south transept and the crossing, brightly coloured and completely engaging. It depicts Thomas Greene, Sheriff of Chester in 1551 and mayor in 1569, with both of his wives, both of whom he outlived. All of their hands were originally clasped before them in prayer, but during the Civil War in the middle of the 17th century, the hands were chopped off because they were considered to be popish, and it is something of a miracle that the rest of the memorial survived.

The Civil War had a serious impact on Chester, culminating with the Siege of Chester that took place over 16 months between September 1644 and February 1646. It must have been a time of great trauma for the cathedral, which must at the same time have supported the local community to the beast of its abilities. The cathedral’s medieval windows, deemed to be idolatrous, were all smashed. A tragedy. It was all replaced with plain glass until modern stained glass was added.

Nick Fry tells how the huge south transept effectively became a church in its own right towards the end of the 15th century, a story of some perseverance by the parishioners of the collegiate church of St Oswalt who had been given the right to use the south transept in the 11th century. In the 13th century, the abbey decided to usher them into their own premises very close to the cathedral, in what is now Superdrug, but they managed to reclaim the south transept in the late 15th century, coming full circle. Wooden screens were erected between the south transept and the rest of the church, effectively segregating it, and these were only removed in the late 1880s, when the south transept resumed its role as a component part of the cathedral proper.

Another, very fine feature of the cathedral, is an ornamental lantern dating to the 17th century that hangs in the baptistry over the 19th century font. Both lantern and font are framed between two lovely Norman arches.

afafafd

The 19th Century Cathedral

The 19th century modifications are pretty much as you would expect. There are some rather unlovable features like some of the mosaics and some of the highly coloured stained glass windows that are teetering right on the perilous edge of being a step too far. These are very consistent with a society that often valued lavishly rich and romanticized themes. But there is also much to admire. There are some imitation medieval windows, that capture at least something of the essence of the earlier periods, and there are some unexpectedly attractive ceilings.

There are several mosaics from this period in the cathedral, some better than others. Most are contained within relatively limited spaces, but the north aisle of the nave has an entire sequence dedicated to scenes from the Old Testament. The one shown here from the 1880s shows the Pharaoh’s daughter finding the baby Moses in his basket on the Nile. Others, behind the High Altar (showing the Last Supper showing Judas, isolated from the group and minus a halo) and the ones in the St Erasmus Chapel, patron saint of sailors and also known as St Elmo, which was co-opted as a memorial to Sir Thomas Brassey by his family, were designed by J.R. Clayton and feature a lot of gold and very bright colouring.

Thomas Brassey was an important personality in Britain’s head over heals expansion of the railways. He was a civil engineer and railway entrepreneur who was such a prolific investor that by the time of his death in 1870 he is credited with having built one in every twenty miles of railway in Britain. He had worked under Thomas Telford when he was young, on the London to Holyhead Road, and he later became a major investor in the company that was formed to rescue Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s enormous ship, Great Eastern after she was launched having bankrupted her owners (see my post about Great Eastern here). He was born in Aldford, south of Chester, and the chapel of St Erasmus, includes a marble bust of Brassey by M. Wagmiller.

Not part of the aesthetic design but unmissable and absolutely endearing in the unfathomable way that so much 19th century engineering is, is the 19th century heating system. In 1999 underfloor heating was installed in the cathedral, but it was not the first heating to be installed. In the 19th century circular cast iron Gurney stoves were added, manufactured by The London Warming and Ventilating Company who bought the patent registered in 1856 by Goldsworth Gurney, surgeon turned engineer. The stove looks like the filter in my wet-and-dry vacuum cleaner, with ribs standing out from a central cylinder, distributing heat in a full circle. It was fired by anthracite, and the entire thing sat in a trough of water, helping to add humidity to the air. The cathedral retains severalof them, and they are in at least 22 other cathedrals too. One wonders what the monks would have made of it. A smaller but still sizeable version was installed in Captain Scott’s hut in Antarctica, carried there by ship. The mind boggles. An interesting modification of Scott’s was the addition of a water tank about the radiator, to heat water, vital for the freezing conditions (for photos see the page dedicated to the stoves on the Antarctic Heritage Trust website).

Not part of the aesthetic design but unmissable and absolutely endearing in the unfathomable way that so much 19th century engineering is, is the 19th century heating system. In 1999 underfloor heating was installed in the cathedral, but it was not the first heating to be installed. In the 19th century circular cast iron Gurney stoves were added, manufactured by The London Warming and Ventilating Company who bought the patent registered in 1856 by Goldsworth Gurney, surgeon turned engineer. The stove looks like the filter in my wet-and-dry vacuum cleaner, with ribs standing out from a central cylinder, distributing heat in a full circle. It was fired by anthracite, and the entire thing sat in a trough of water, helping to add humidity to the air. The cathedral retains severalof them, and they are in at least 22 other cathedrals too. One wonders what the monks would have made of it. A smaller but still sizeable version was installed in Captain Scott’s hut in Antarctica, carried there by ship. The mind boggles. An interesting modification of Scott’s was the addition of a water tank about the radiator, to heat water, vital for the freezing conditions (for photos see the page dedicated to the stoves on the Antarctic Heritage Trust website).

The most irritating aspect of the 19th century work was George Gilbert Scott, who clearly loved medieval architecture and sculpture, but could not prevent himself making what he believed were improvements on the original conceptualization. Scott was given a regrettably free hand with the renovation work, and reimagined much of the original architecture with his own vision. One cannot argue that he was attempting to do anything but good, albeit with a lot of self-indulgence coming into play, but he often got it rather dreadfully wrong. On the other hand, I am a pushover for 19th century floor tiles, and he produced some rather good ones, including the rectangular section of the Crossing (beneath the tower). He was also responsible for the current organ, which incorporated elements from an earlier 19th Century organ, and has been extended since. It sounds marvellous.

The most irritating aspect of the 19th century work was George Gilbert Scott, who clearly loved medieval architecture and sculpture, but could not prevent himself making what he believed were improvements on the original conceptualization. Scott was given a regrettably free hand with the renovation work, and reimagined much of the original architecture with his own vision. One cannot argue that he was attempting to do anything but good, albeit with a lot of self-indulgence coming into play, but he often got it rather dreadfully wrong. On the other hand, I am a pushover for 19th century floor tiles, and he produced some rather good ones, including the rectangular section of the Crossing (beneath the tower). He was also responsible for the current organ, which incorporated elements from an earlier 19th Century organ, and has been extended since. It sounds marvellous.

Located next to the Romanesque arch in the north transept is a tiny and extraordinary back-lit copy of a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder. What makes it extraordinary is that it was painted onto a caterpillar net, like a cobweb. I had never heard of this 19th century tradition, but it apparently became very popular in Austria and there are only around 60 examples remaining in existence.

Located next to the Romanesque arch in the north transept is a tiny and extraordinary back-lit copy of a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder. What makes it extraordinary is that it was painted onto a caterpillar net, like a cobweb. I had never heard of this 19th century tradition, but it apparently became very popular in Austria and there are only around 60 examples remaining in existence.

There are a lot of sculptural memorials to the deceased hanging from the walls, most of them relating to tombstones below, under the cathedral floor. All of them are interesting, but some of them have slightly unusual inscriptions, of which three are shown below, and are side by side in the cathedral, all in the north quire aisle (number 15 on the plan at the top).

The Cathedral in the 20th – 21st Centuries

There was no sudden break between the 19th and 20th centuries, but the onset of war in 1914, and then again in 1936, must have raised the cathedral’s role as a place of solace and support. In the south transept there are a number of memorials commemorating military sacrifice from various periods, but those from the two World Wars are characterized by a brevity and understatement that makes them particularly touching.

At the same time, the cathedral continued to be developed architecturally. One of the most remarkable innovations of the early 20th century, and one of its best, was the glazing of the cloister arcades the personal mission, in 1920, of the new Dean, Frank Bennett. As well as the main window lights, which show saints, including St Werburgh and her aunt St Ethelreda, archbishops of Canterbury, holy days or important festivals, there are also little memorials that are far more personal and provide a link with some of the people who were part of Chester’s everyday life: one commemorates the Cheshire mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew Irvine. Another is dedicated to John Elliott “Physician of this City.”

dfasdaf

Moving more firmly into modern times, more recent experiments with modern sculpture and stained glass are worth thinking about. How you feel about any of the modern contributions to Chester Cathedral is a very personal thing. Some of the modern stained glass is inoffensive, some of it is a lot less successful. The garth has been beautifully planted with spring bulbs, but its dominating feature is a substantial modern sculpture in the centre, and I would have preferred the monastic peace without the contrived intrusion, although I loved the sound of the fountain. I could also seriously live without the big flat-screens, which show as white rectangles in the photograph on the left at the top of this section. I mentioned above that there was purple lighting in the nave when I returned to take photographs on March 3rd. The overall impact was distinctly weird, but probably had relevance to an upcoming event, and was only temporary.

Moving more firmly into modern times, more recent experiments with modern sculpture and stained glass are worth thinking about. How you feel about any of the modern contributions to Chester Cathedral is a very personal thing. Some of the modern stained glass is inoffensive, some of it is a lot less successful. The garth has been beautifully planted with spring bulbs, but its dominating feature is a substantial modern sculpture in the centre, and I would have preferred the monastic peace without the contrived intrusion, although I loved the sound of the fountain. I could also seriously live without the big flat-screens, which show as white rectangles in the photograph on the left at the top of this section. I mentioned above that there was purple lighting in the nave when I returned to take photographs on March 3rd. The overall impact was distinctly weird, but probably had relevance to an upcoming event, and was only temporary.

One of the modern touches does a good job of linking past and present, and draws some attention from visitors, a fascinating American quilted representation of the Mystery Plays. Katie says that it was once kept in an inlet at the approach to the main entrance, and that it was stolen. The police were involved and it was eventually returned and is now safely installed in the body of the cathedral. We stood and looked at it for a while, picking out scenes that are particularly intriguing or amusing. The Mystery Plays are still enacted today every five years, and are coming up again in 2023.

One of the modern touches does a good job of linking past and present, and draws some attention from visitors, a fascinating American quilted representation of the Mystery Plays. Katie says that it was once kept in an inlet at the approach to the main entrance, and that it was stolen. The police were involved and it was eventually returned and is now safely installed in the body of the cathedral. We stood and looked at it for a while, picking out scenes that are particularly intriguing or amusing. The Mystery Plays are still enacted today every five years, and are coming up again in 2023.

The former monks’ dormitory is now the Song School. The dormitory had been replaced by a concrete roof by the time that the decision was made to build the Song School over the rib-vaulted chapter house vestibule, the slype and the song practise room, and is accessed from the day stairs, by which the monks entered the cloister when it was still an abbey. It has been very sympathetically done from the outside view. The red sandstone is very new and clean, but will weather in time and I like that it is differentiated from the older stone, not pretending to be something that it is not.

Addleshaw Tower. Photograph by Mike Peel. Source: Wikipedia

Not part of the cathedral building, but in its surrounding gardens and best seen from the Chester Walls is the Grade II-listed standalone bell tower, the Addleshaw Tower, something that is likely to divide opinion. I rather like it, although a lot of people don’t. It was built to house the bells after they had been renovated, and when the original bell tower was deemed to be rather too fragile to support the weight without additional structural work that could have been excessively intrusive. The idea of an external bell tower was a neat solution, but of course the design was controversial. The design by George Pace was displayed at the Royal Academy of Art’s annual Summer Exhibition in 1969, and the foundation stone was laid by Lord Leverhulme in 1973. The main external building materials are pink sandstone and Welsh slate, which hide a reinforced concrete frame. It has been well maintained and still looks brand new.

asfadsfasf

Those who are working behind the scenes today to sustain Chester Cathedral for the modern world have done an excellent job of making the transition from place of worship to tourist attraction, whilst ensuring that there are still spaces available for private prayer, with plenty of quiet areas in which to light candles. I was particularly touched by the prayer for Ukraine placed in St Werburgh’s Chapel at the east end of the north aisle (number 16 on the plan above).

Those who are working behind the scenes today to sustain Chester Cathedral for the modern world have done an excellent job of making the transition from place of worship to tourist attraction, whilst ensuring that there are still spaces available for private prayer, with plenty of quiet areas in which to light candles. I was particularly touched by the prayer for Ukraine placed in St Werburgh’s Chapel at the east end of the north aisle (number 16 on the plan above).

Chester Cathedral works, and it is a good example of how to get it right. I have always struggled a little with churches and cathedrals, mainly because the blend of old and new is often (but not at Chester) so jarring, and so difficult to process. Tatty vestries, rows of plastic chairs, and aged sun-bleached pinboards with dog-eared notices often make for a dismal experience. In spite of modern seating, there is nothing remotely dismal about Chester Cathedral, which balances modern lighting (not usually purple) and underfloor heating with daily services, and a nice blend of dignity, heritage, practicality and the divine, celebrating its more remote past and retaining a sense of purpose. I’m not quite sure how it has been pulled off.

At the moment the far west end of the name is being restored, and that is one of the most notable and admirable signs of modern activity, but although this is just one restoration project, this is probably a never-ending story with small pockets and larger programmes of of work being undertaken all the time, and there are probably many more underway out of sight of the public.

Final Comments

Later pillar somewhat ruthlessly positioned in front of one of the Norman archways in the cloister. My favourite bit of the cathedral, because it is so human

It is interesting that when it comes to describing the cathedral today, it is the abbey that stands out as the main influence on everything that happened subsequently, even the 19th century attempts to give it a new touch. I was expecting more 16th-18th century interventions, but even though the Norman has largely been eliminated by the abbey’s Gothic phases, it is the pre-Dissolution abbey that still speaks out, even through a veil of 19th century and even more recent modifications.

I tend to bang on about multi-layered experiences when talking about enduring archaeological and historical buildings, because the sense of time being both visible and concealed, thick and thin, horizontal and vertical, subtle and brash usually hits me like a tidal wave. Chester Cathedral, incorporating the remains of the 7th Century shrine and remains of Saint Werburgh, was built, rebuilt, renovated and reinvented over 600 years, and is still in use today as both a place of worship and a tourist resort. It fills the head with temporal chaos, but it’s a good chaos because it represents the accumulation of history, and even though it scrambles the brain, that historical scramble has an awful lot to say. The challenge is to get to grips with the narrative.

I am colossally aware of the futility of making the attempt to do justice to the cathedral in a single post. The guide books help enormously, doing an excellent job of trying to compress a staggering amount of information into something digestible, but it’s still a big ask to contain centuries of change within a restricted format. If you are are going, I recommend either booking a tour or buying a guide book online before you go and reading it first.

The organ, which dates to the 19th century, was being played whilst I was there to take photos, a stunning sound, and if you want to get a sense of how wonderful it is, have a look and listen at this YouTube video of an hour-long concert held in Chester Cathedral, beginning with the Overture to Mozart’s Magic Flute, in which the cathedral’s is being played by the remarkable Jonathan Scott, who talks about how the organ delivers its sound via keys, pedals and stops. There is some great footage of Jonathan Scott’s finger work on all four tiered keyboards, and for me it was a particular revelation to see the amazing foot work required. I had no idea. There are also some great internal views of the cathedral on the video. It lasts for an hour, and is a truly illuminating insight into organ music.

Visiting and accessibility

We drove in to Chester, and parked at the Little RooDee car park on Grosvenor Road, just round the back of Chester Castle. It is a long-term car park, £5.00 for the whole day, and worth it for a visit to the cathedral, where there is so much to see, particularly when you are planning on lunch as well.

We drove in to Chester, and parked at the Little RooDee car park on Grosvenor Road, just round the back of Chester Castle. It is a long-term car park, £5.00 for the whole day, and worth it for a visit to the cathedral, where there is so much to see, particularly when you are planning on lunch as well.

Full details of the cathedral’s opening times etc are at www.chestercathedral.com, and should be checked in case things change. Photography is permitted, although lighting is very low. I didn’t check about flash and cannot find any reference to it on the website. Access is currently free, but suggested £4.00 donations are very much appreciated and deserved – you can donate in the reception area by popping money into an enormous glass coffer, by handing it to the person on the till, or by buying Lego blocks of the superb Lego cathedral in the nave, which is such fun (a pound a block) and very useful for getting a birdseye view on the cathedral buildings. All the contributions go to repairs, conservation and restoration.

Regarding accessibility, there is not much to worry about. It has not been converted throughout for wheelchair access, at the time of writing, but there is a ramp from the reception area into the main cathedral and there is still a lot to be seen without tackling steps. For those on foot, there are only a few stone steps here and there, and for most people these are too few to worry about. Most are very shallow and easy to tackle, and those that are likely to trip you up in the low light are painted white along the edges. Like all old buildings, however, keeping an eye on where your feet are going is a very good idea.

If you are keen on stained glass, be warned that nearly all of it is 19th Century and modern, and that if you want to get a good idea of it, a bright day helps.

If you are keen on stained glass, be warned that nearly all of it is 19th Century and modern, and that if you want to get a good idea of it, a bright day helps.

On both visits I was very lucky to be trdated to live music. There was choral singing in the south transept when I was there with Katie, the singers informal in jeans and comfy clothes, filling the entire cathedral with a gentle but lovely sound. This happens between 10.30 and 12.00 on Fridays in the south transept, led by Ella Speirs. According to her website, sing.dance.love., the music was developed by Taize, an ecumenical community in France founded after the Second World War, which creates a harmony in song using short phrases from scripture. It was a fabulous accompaniment to the visit, for which my thanks to those who took the trouble to lend their voices to the morning. On the day when I was taking photographs, the following week, an organist was playing, and the sound was glorious.

Our final stop was the monastic refectory, a tall, light-filled space, now a really good coffee shop/café where we had lunch. Very appropriate. As you wait for your food to arrive you can admire the glorious 1939 hammer-beam ceiling, the Gothic architecture, the modern stained glass window, and soak up the atmosphere. I had latte and a Welsh rarebit, the latter served with a gorgeous coleslaw that tasted anything but synthetic and a light and ultra-fresh salad with crispy oak-leaf lettuce, crunchy cucumber and firm but juicy little cherry tomatoes, all tossed in just the right amount of balsamic dressing. The cheese was golden, perfectly melted, deliciously browned in places and gorgeous. I’ll be stopping there again.

The garth within the cloister, a completely secluded area. The Water of Life sculpture is in the foreground, and the new sandstone of the Song School is clearly visible behind the cloister arcade. Photograph by Harry Mitchell, Source: Wikipedia

We exited through the gift shop, as you do, where there are postcards, books, booklets, choral music, DVDs, jewellery, games and other items. If you are interested in exploring the subject of the cathedral’s stained glass, you can buy a booklet about it, and the same with the misericords. The shop is very nicely done, and you can buy your stamps for postcards at the same time. I came away clutching postcards, stamps, a guide book and the little leaflets about the misericords and the cloister windows.

There are “Cathedral at Height” tours that take you to upper layers in the cathedral, all the way to the top of the tower, and although I haven’t yet done this, Katie says that a reasonable amount of fitness is required (216 steps), and anyone suffering from claustrophobia or vertigo may want to think twice. I suffer from neither, and am seriously looking forward to the experience and the views from the top of the tower. Find out more on the Chester Cathedral website.

fasfasfasd

Sources

When the bells were removed, George Pace designed a ceiling decoration in gold on wood in 1973, to seal the bell tower, that still draws the eye and looks stunning

For the first time, my main source cannot be pinned down to a publication. Thanks very much again to Katie Crowther, Chester Green Badge tourist guide for introducing me to Chester Cathedral, who says that Nick Fry’s generous contribution of his expertise on the cathedral’s history was a great source of information for all those on the Green Badge course. His guide book is listed below. I did not take notes, and the following sources helped me to nail down facts that I had half-remembered. Any errors in the above are, as usual, all my own work 🙂

fdasfsdafasf

Books and papers

Burton, J. and Kerr, J. 2011. The Cistercians in the Middle Ages. The Boydell Press

Fry, N. 2009. Chester Cathedral. Scala

Greene, J.P. 1992. Medieval Monasteries. Leicester University Press

Hiatt, C. 1898. The Cathedral Church of Chester. A Description of the Fabric and A Brief History of the Episcopal See. George Bell and Sons. Available on the Internet Archive

Hodge, J. 2017. Chester Cathedral. Scala

Smalley, S. 1994. Chester Cathedral. Pitkin Guides

Soden, I. 2021 (second edition). The First English Hero: The Life of Ranulf de Blondeville. Amberley

Pamphlets

Brooke, J., Fry, N., Ingram, B., Moncreiff, E. and Thomson, J. (no date). The Windows of the Cloister. Chester Cathedral

Brooke, J., Fry, N., Ingram, B., Moncreiff, E. and Thomson, J. (no date). The Windows of the Cloister. Chester Cathedral

Smalley, S. (additional research, Fry, S.) 1996. Chester Cathedral Quire Misericords. The Pitkin Guide. Chester Cathedral.

Uncredited 2010, with an introduction by the Dean of Chester. Refectory Treasures. Chester Cathedral

Websites

Antarctic Heritage Trust

The Gurney Stove in Antarctica

https://nzaht.org/gurneystove/

British History Online

Chester Cathedral

A History of the County of Chester: Volume 3. Originally published by Victoria County History, London 1980, pages 188-195

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/ches/vol3/pp188-195

Chester Cathedral

https://chestercathedral.com

Historic England

Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1376398?section=official-list-entry

Chester Mystery Plays

About the Plays. Keeping History Alive and Well

https://chestermysteryplays.com/discover/history/

Earls of Chester Family Tree

Chester ShoutWiki http://chester.shoutwiki.com/wiki/File:EarlsTree2.jpg

Dr Thomas Pickles

Why did St. Werburgh of Chester Resurrect a Goose?

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GhWq2ZS3XkE

Historic England

Official list entry

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1376398?section=official-list-entry

JPP (CDM) Ltd

Song School, Chester Cathedral

https://jppcdm.co.uk/project/new-song-school-constructed-on-medieval-cloisters-at-chester-cathedral/

Sing.Dance.Love

Fridays 10.30-12 at Chester Cathedral in the South Transept

https://www.singdancelove.co.uk/taize-at-st-peters