Introduction

The Roman bath-house at Prestatyn, discovered in the 1930s, is located in a rather nice little housing estate on the edge of Prestatyn, which hems it in but does not overshadow it. Today the site is pleasantly presented in its own space, accessed via a gate. There are two information posters, and a raised area from which one can look down into the site before walking in and on it. There has been a lot of work carried out to stabilize and preserve it with concrete and mortar, so it is a distinct mix of old and new, but the essential layout has been preserved. On the day that we were there, a blue tarpaulin was lying over a small part of the walkway around the site, presumably either due to unsecured damage or to protect repairs.

The Roman bath-house at Prestatyn, discovered in the 1930s, is located in a rather nice little housing estate on the edge of Prestatyn, which hems it in but does not overshadow it. Today the site is pleasantly presented in its own space, accessed via a gate. There are two information posters, and a raised area from which one can look down into the site before walking in and on it. There has been a lot of work carried out to stabilize and preserve it with concrete and mortar, so it is a distinct mix of old and new, but the essential layout has been preserved. On the day that we were there, a blue tarpaulin was lying over a small part of the walkway around the site, presumably either due to unsecured damage or to protect repairs.

Excavations in the 1930s (Professor Robert Newstead), the 1970s and again in the 1980s (Kevin Blockley for CPAT) revealed an Iron Age farmstead (to be described on a future post) and a Roman and Romano-British (indigenous) settlement dating from the late 1st century AD, some time soon after AD 70. The combined excavations revealed a Roman complex of structures over a number of periods. The main period of Roman and Romano-British activity, spanned two periods, defined by Blockley as IIA and IIB. This included eleven timber buildings, seven in Phase IIA and four in IIB, a water well, and three stone-built buildings, including the bath-house with its furnace and its water management system. The bath-house itself was built in around AD 120, quite late into the history of the site, and was extended in AD 150. The entire group of buildings appears to have gone out of use towards the end of the 2nd century. Originally it was thought that the bath-house and other buildings may have been outliers of a fort. There is no known fort in north-east Wales in spite of the existence of other Roman sites and three Roman roads, and it was hoped that this might fill a gap in the data.

The Bath House

Today all that remains visible of this complex of buildings is the bath-house. When it was found, much of the bath house and surrounding area were covered with c.60cm (2ft) of rubble, described by Newstead as: “tumbled masonry, broken roof tiles, bricks and quantities of tile-cement flooring etc” a well as box tiles and ridge tiles.

The foundations of the bath-house preserve the main features of a very small but classic Roman bath house, the plan of which is clearly visible on the ground. It measures c.11.7m x 4.5m (c.38 x c.15ft). What you can see today was the under-floor part of the bath-house. Over the top of most of these features, except for the D-shaped plunge pool, would have been a tiled floor. The bath-house was built in two phases.

The bath-house in AD 120

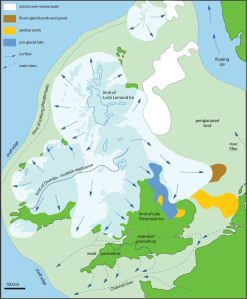

The walls of the building consisted of three courses of ashlar (dressed stone, to present an attractive appearance) filled with rubble and mortar to create the thick walls visible today. The rubble within the outer walls was locally sourced, probably picked out of glacial soils near the site. Of the exterior ashlar, Newstead found purple micaceous sandstone blocks in situ along the base of the northern wall of the bath house, the nearest source of which was around 6 miles away (and can be seen in use today at Rhuddlan Castle and St Asaph’s Cathedral). Broken roof tiles were also used in the construction. Inner walls might have been plastered and could have been decorated. The roof was tiled, and provided with decorative triangular antefixes showed LEG XX V V legend as well as the legion’s wild boar emblem, which like the tiles were provided with stamps identifying them as work of the 20th Legion. The 20th Legion’s tile-works at Holt near Chester clearly provided the tiles and bricks required or the bath-house in AD 120, and it is possible that they assisted with the construction works, but there is no sign that this was a legionary base, or that the 20th Legion controlled whatever activities took place at the site. Apart from the tiles and bricks, all of the stone used at the site was sourced within a few miles of the site.

The first phase of the bath-house with the hot room and warm room in Period IIA. Source: Blockley 1989

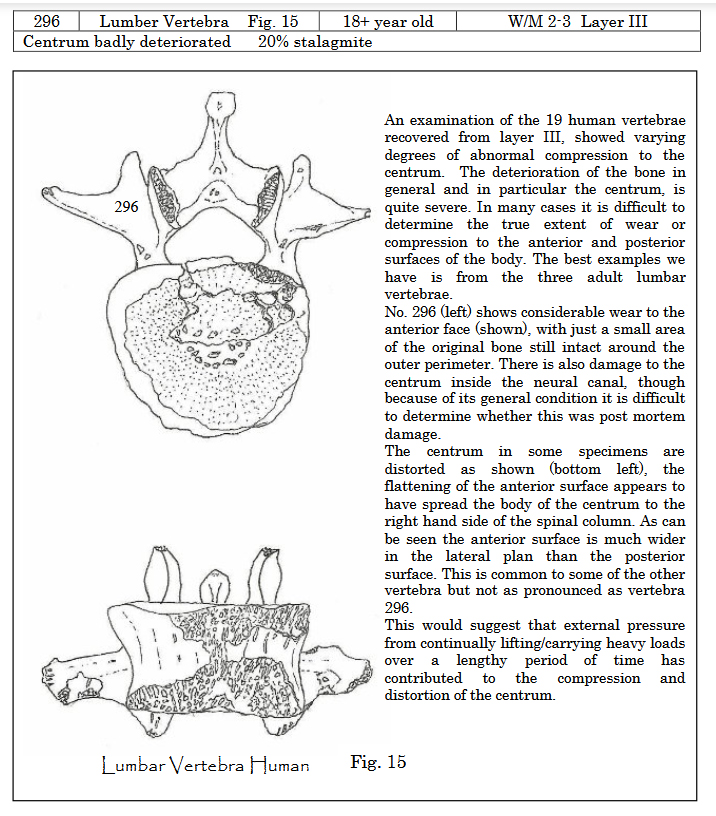

The plan to the left excludes the later cold room (frigidarium) with the D-Shaped plunge bath, showing the stone-built components of the bath-house in AD 120, when the bath house was built. There is no sign of a stone-built cold room, which was was either missing, which would be very unusual, or was built of wood. The two rectangular rooms, both of which sat over two hypocausts were both built in this first phase. Hypocausts are artificial floors set on small pillars made of bricks and tiles (pilae) into which hot air, supplied by a furnace, is channelled.

In the tepidarium, Room B, Newstead found only two of the short hypocaust pillar bases, each bearing the stamp of the 20th Legion. An internal doorway gave access to the Room C, the hot room or calidarium which was nearest to the furnace, where the remains of another fourteen pillars (pilae) survived. The pillars were made of a c.28 x 28cm (11 x 11 inches) brick stamped with the 20th Legion’s name: LEG XX V V (an abbreviation of Legio XX Valeria Victrix: 20th Legion, Valiant and Victorious). These were placed face down into the floor. These was then topped with tiles c.19 by 19cm (7.5 x 7.5 inches) set into clay, none of which were stamped. The hypocaust bricks and tiles were sourced from the specialist tile and brickworks at Holt on the Dee just south of Chester.

Illustration of a 20th Legion stamp on one of the bath house tiles. Source: Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB-2463_29_xiv)

The technical challenge for the builders came in the heating process, which required a furnace to provide the required heat to the two rooms. The remains of the furnace were found by Newstead, built into the centre of west end of the building and projecting 1.4m (4ft 6inches) beyond it, providing heat via a channel known as a praefurnium. Its floor was originally flagged with large blocks of purple sandstone. You can still stand in the praefurnium, shown left, to look into the hot room (caldarium, room C) and the warm room (tepidarium, room B) room beyond. Ducts or flues conveyed heat from Room C to Room B.

Like feeding a steam engine, this furnace would have required a considerable amount of fuel to keep the heat supplied, and this would have required manpower both to collect the right sort of wood and to feed it into the furnace. There would have been storage nearby to dry and store wood.

The video below is a 3-D animation of how the hypocaust at Brading Villa on the Isle of Wight functioned, which gives a good idea how the smaller example at Prestatyn worked too:

Also see the excellent video at the end of the past where the Roman hypocaust at the bath house at Bath are described.

Beyond the bath-house, to its east, was a stone-lined well, and a drain that was also partially stone-lined. The well was 1.6m deep and 1.1m sq at its base, flaring to 2.5m wide at its top. It was probably used to supply the bath-house and the two nearby buildings R4 and R5, both of which were copper-alloy workshops dating to IIA.

AD 150 – the extension of the bath-house

The Bath house as it was found when Newstead excavated it. Rooms B and C were included in the original building of AD 120; Room A, the D-shaped plunge-pool, and the masonry drain under the cold-room floor and a drain out of the plunge-pool were added in AD 150. Source: Newstead 1937 (National Library of Wales)

As already mentioned above, there is no sign that a cold room was included in the first phase of the bath house. It may have been built in timber, now lost, or it may not have been built at all. Perhaps given the climate, a rectangular cold room and accompanying apse-shaped cold plunge pool, Room A, were not considered necessary, although this is not true for other bath-houses in Britain. The stone-built cold room was only built 30 years after the original construction of the bath house, measuring 32m by 4m (104 x 13ft). A new entrance was presumably provided in the cold room, with an internal doorway into the warm room.

Plan and hypothetical elevations of bath-house water supply. Source: Blockley 1989, fig.28 p.51. Click image to enlarge.

The accompanying D-shaped plunge pool was lined with a 12cm (c.4.5ins) thick layer of opus signinum (a type of waterproof pink mortar) on a base of limestone and mudstone fragments set in to clay. It was around 1.4m (4.5ft) deep. Blockley describes the water supply to this plunge-pool as the “most completely recovered layout known in Britain,” which included a stone and timber drainage channel, an aqueduct fed by a natural spring, and possibly water tanks.

The diagonal drainage channel crosses the cold room, originally under the floor of the cold room. Blockley believes that this was probably connected to an internal basin. A second drain leads from the apex of the D-shape as shown on the diagram above, the first 1.6m (c.5ft) within the bath-house had a floor of 40cm sq (c.15.5cm) bricks and was lined with limestone. South of the masonry section it was made of wood, and extended for 14m (c.46ft). The wooden uprights survive along one section, probably used to hold planks in place along the sides of the drain, which was 25cm deep and 70cm wide with stakes at c.20cm (c.8ins) intervals.

The line of the aqueduct, found in the 1980s excavations, was indicated by a row of parallel postholes. It ran from the east of the bath-house into the plunge-room, running over the top of the external drain. Nine of the postholes had timbers of alder-wood in situ, up to 65cm long and 35cm (c.13.5ins) diameter. The distances between timbers varies along the route, between 1m (c.3ft) and 1.5m (c.5ft). A water tank may have been sited part way along. It is thought that a spring further up the slope would have taken the aqueduct over a gradient of some 3m.

Using the Roman bath-house

A section of one of the information boards at the site showing the hot room, far left next to the furnace, the warm room in the middle and the later cold room and plunge pool. Click to expand and see the text clearly.

Had you been lucky enough to be a Roman official with access to a local bath house, bathing followed a sequence of steps that was imported from the core of the Roman Empire. Movement was through a sequence of warming and cooling experiences.

Roman bathing followed a specific process. Bathers would get changed, and in bigger bath-houses there was a room put aside for this. They would then progress from the unheated cold room (frigidarium) to the warm room (tepidarium) to acclimatize and then to the hot room (caldarium) before heading back to the cold room to cool down and take a cold dip in the plunge-pool. All well and good in southern Italy during a balmy Mediterranean summer, and perhaps even in a good Welsh summer, but that cold pool really didn’t look that appealing to me on a chilly day in April! A bathhouse was often accompanied by an outside, walled exercise area, but there is no indication that the Prestatyn bathhouse offered such a facility.

The Melyd Avenue complex of buildings

1930s survey of the masonry buildings at the site, showing the stone buildings including the bath house (B3 near the bottom of the image) and the trial cuts cut across the site. Source: Newstead 1937 (National Library of Wales)

The bath house was part of a bigger complex of buildings, only some of which have survived. The site was discovered and informally investigated in 1933 by Mr F. Gilbert Smith, who noted objects and carried out surveys. It was thought that it might have been a component of a Roman fort. It was excavated between 1934 and 1937 by Professor Robert Newstead, who found both the bath house (his Building 3) and two other stone-built buildings (Buildings 1 and 2). He also investigated a section of “paved causeway” found by Smith, and made 9 “cuts” (investigative trenches) at other parts of the site. The bath house has been described above. Building 1 consisted of three rooms in a line, with what had once had a tiled floor at one end, and measured c.19 x c.7m (62ft 6ins by 23ft). It produced a coin of Vespasian dating to c. AD 71, as well as pieces of a Samian ware platter also dating to the late 1st century. Samian ware (terra Sigillata) is a bright, glossy red high-status pottery often highly decorated in relief, which is often stamped with the manufacturer’s mark, and is very useful for dating (see image further down the page, and the excellent video at the end of the post by Guy de la Bédoyère). Building 2 was less clearly defined and far less informative, at least c.11m long (36ft), producing a single undated piece of amphora, and had been damaged by fire.

The cut through the section of “paved causeway” identified by Smith and shown on the above plan revealed that it was made of flat sandstone slabs over large pine logs on top of “a mess of brushwood in a peaty matrix.” Within these layers there were Roman potsherds and pieces of window glass as well as animal bones. The other cuts revealed no features but the one in front of building 3 produced a piece of millefiori glass, 7 pieces of window glass, some fragments of a glass flask and a small black counter as well as some samian ware. In 1938 further excavations produced no more buildings, and consisted mainly of taking sample cuts through the site, and these produced Roman levels that contained fragments of Roman objects. All of the data from the site over the years of excavation placed it within the later 1st to the later 2nd centuries AD. As well as tiles and antefixes stamped with 20th Legion stamps, diagnostic finds included a Vespasian coin, some distinctive pieces of samian, other dateable types of pottery and fragments of decorative and glass as well as some fittings for horses and some jewellery.

The 1972-73 rescue excavations followed another building development in nearby Prestatyn Meadows, during which Roman materials were found, including a column base and tiles stamped with LEG XX VV. Excavations could not take place at the precise location of the discovery due to building regulations, and were therefore carried out a little to the south, with three trial trenches opened to sample the area. No structural remains were found, but there were plenty of objects dating to the late 1st and 2nd centuries AD, consisting of building fragments and domestic rubbish including samian, coarse ware, window glass, flint, animal bones and coal.

The 1984-5 excavations, undertaken and published by Kevin Blockley in 1989 on behalf of the Clwyd and Powys Archaeological Trust (CPAT), considerably expanded the view of what was going on at the site. Excavations took place over two seasons, or 47 weeks, and uncovered 1544 sq m (c.5065) sq ft). As well as both pre-Roman and post-Roman discoveries, he found eleven timber-built buildings over two phases of Roman occupation, most of them with both postholes and stakeholes, indicating a probable timber frame with wattle-and-daub wall construction. Over 2000 small-finds were excavated. Blockley and his team were also responsible for the discovery of the well and the water supply to the new cold room and plunge pool added in c.AD 150, described above. Most importantly, the excavations were able to make more sense of the chronology of the site, making use primarily of pottery types to derive date-ranges for different buildings and phases.

Sequence diagram for Period II, and location plan. Source: Blockley 1989, fig 31 p.54. Click image to enlarge.

Blockley concludes that the earliest phase of the site was building R1, which, judging by Flavian date pottery and Vespasianic coins, both of which showed significant use-wear, suggest a start date somewhere in the AD 70s. The bronze-smith workshops were first established in around AD 90-100 with buildings R3 and R4, and the site continued to develop until around AD 160, when it was abandoned. The bath-house, established in AD 120, was therefore built when the site was already some 50 years old.

The data in the timber-built buildings included features (like postholes, wall trenches, hearths and floors) and finds (industrial tools, industrial waste, and manufactured objects like horse-ware fittings, whetstones, querns, millstones, spindle whorls, pestles and mortars, brooches and finger rings, tableware glass, window glass, both fine and coarse pottery, ceramic crucibles and moulds, items made of bone, leather, wood and clay, and bricks and tiles). Pulling all the data from all of the timber buildings together, Blockley found that a picture of a copper-alloy works emerged, an industrial site that was producing goods that were probably purchased both locally and sent further afield, making use of the Roman communication network.

The metalwork, including some lead (including weights and pot rivets) and heavily corroded iron, was dominated by copper-alloy, a form of bronze. This was used to make brooches, studs, plates, simple finger rings, pins, needles and shield-bindings. Of particular interest are the enamelled brooches, with coloured enamel inlays in different patterns, of which a number of complete or near-complete examples were found. These include Colchester, Headstud, trumpet, plate and penannular types, all popular fashion items in late 1st and 2nd century Britain, and some unclassified types. Only one of the finger-rings stood out, and this was a copy, in tin, of a 2nd century Roman type of silver ring using yellow glass in place of a precious or semi-precious stone.

The glass includes 600 fragments, 377 of which were table- and kitchen-ware (the bulk of which were bottles) and 159 from window glass. It all falls within the time-range of the first half of the 1st century AD to the end of the 2nd century. Some of the table-ware was brightly coloured and highly prestigious, but most of it was blue-green. The window glass is thought to have come mainly from the bath-house, and was notably smooth and of very high quality.

The pottery assemblage, consisting of broken pieces, included both fine wares and coarse wares. It ncluded items made of local raw materials, making up 44% of the assemblage, and imports. The imports included black-burnished ware from Dorset (10%), samian (14%) and amphorae from Spain and Italy (19%). A small number of white-ware flagons from Mancetter were also found (1%). Some were manufactured from the Holt kilns, near Chester, and others were probably made on the Cheshire plains.

Spelt. Source: Wikipedia

Botanical and faunal remains give some indication of diet. Although botanical remains tend to be fairly rare, the waterlogged conditions in the well preserved 13 samples of plant remains that were sent for analysis, and included carbonized grain, chaff and seeds. The well was abandoned after Period IIA, so these survivors probably belong to IIB, contemporary with the second phase of the bath-house. Of the grain remains, spelt was the dominant species, followed by emmer wheat and small amounts of barley and oats, probably all crop-processing waste. Spelt is particularly resistant to cold, wind, diseases and pests, so would have been the most suitable crop for an exposed area without good quality soil. Weeds found in the samples represent those that grow in amongst crops, and are well adapted to disturbed conditions.

Animal remains, some of which retained butchery marks, include sheep, the dominant species, cattle and pig remains. Some fowl were kept and horse bones were found in small numbers. Wild species include red and roe deer, goose, duck and hare.

Interpretation – what did these buildings represent?

Although this all suggested a well-built if fairly modest settlement, neither Newstead nor Blockley discovered any indications of a potential fort. A ditch with a clay “rampart” was found, but this was later interpreted as an enclosure for the settlement. However, the idea that there may have been a fort at Prestatyn continued to linger, as this could have been a civilian settlement on the outside of a fort. In 1973 Roman building rubble was found c. 30 to 40m south of the bath-house, and judged to date to not later than c. AD 150. This rubble included a column base, some 20th Legion roof tiles, and fragments of building stones, pottery, window glass, fine and coarse pottery and flint, all dating to the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. When planning permission was granted for the housing estate, it was excavated by archaeologists in the 1980s, published in 1989, discussed below, producing numerous timber buildings of 1st-2nd century Roman date. Geophysical survey in the grounds of Ysgol y Llys in the mid-1980s and further evaluations in 2001 and 2003 failed to provide any Roman features or material. Overall, the idea that the bath house was associated with a fort has now been rejected.

So what was the bath house doing in this particular location? It so often happens that prominent Roman sites lie in unexpected places. The one that springs to mind is Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum) which was once a bustling walled town in Hampshire, an administrative capital with all the buildings, facilities and services that Roman Chester once had, but is now just a set of fields and ruined walls in agricultural land, which requires (and has received) research and explanation. The Prestatyn settlement is very small by comparison, but equally requires contextualization and explanation.

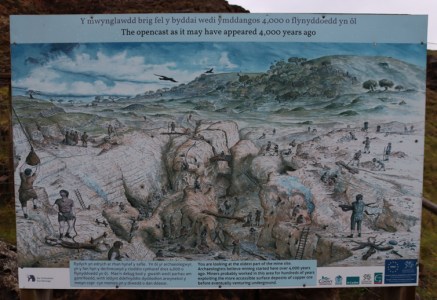

Detail from one of the information boards, showing the relatve locations of the bath house and its associated buildings, the nearby lead mines and St Asaph, which may have been Roman Varis.

The buildings themselves and the objects found suggest that the site probably represents an industrial site with a Roman lead-mining operation and harbour, which attracted Romano-British metallurgists who set up workshops nearby. There was certainly a lead ore mining operating dating to the Roman period in nearby Meliden, and this seems like a good match for the location the site, sitting between the mines and the sea. It is not the only lead-mining operation in northeast Wales. The best known source of lead locally in the Roman period was Halkyn Mountain, which had rich veins of lead ore (galena). Another site exploited by Roman miners was in the Pentre-Oakenholt area of Flint, accompanied by a number of masonry buildings, and another was found at Pentre Farm, where timber structures and 20th Legion stamped tiles were found.

David Mason has described the Prestatyn site as “most likely a transhipment centre if not the actual focus of ore-smelting.” He believes that one of the ingots of lead found in Chester, dated to AD 74, probably originated in Prestatyn (see image below). It was marked with the word “DECEANGL,” meaning “mined in the land of the Deceangli tribe,” in whose territory it was found. According to Roman records, at the time of the Roman conquest, most of Britain was divided into tribal areas, and the Deceangli were based in northeast Wales, giving the area a geographical as well as a tribal identity. The ingot (or pig) was discovered in 1886 in the remains of what is thought to have been a Roman timber quayside on the Dee in Chester. This quayside location for the ingot, together with the 20 ingots of lead found in the river at Runcorn, thought to have been lost in a shipwreck, underline the importance of moving lead by boat.

Lead ingot from a river jetty site at the edge of Chester racecourse dating to 74AD. Source: David Mason’s “Roman Chester. The City of the Eagles,” p.45

In fact, given the sheer quantities that David Mason estimates would have been needed for the building of the fort at Deva (Chester), it is difficult to imagine the significant amounts being moved any other way: 39 tons or 50 wagon-loads for water pipes, and 34 tons or 43 wagon-loads for reservoir linings.

Lead stamp used to mark bread. The abbreviated inscription reads “Made by Victor of the Century of Claudius Augustus”

The Coflein report suggests that “a vicus-like settlement associated with a harbour installation designed for the shipment of lead and silver from nearby the mines, though its precise nature is unclear.” A vicus was a small settlement (plural vici), usually rural, that springs up on the edges of a centre of Roman activity such as a fort or mining or quarrying operation in order to sell goods and services. It has been suggested that some of those connected with larger military forts were established intentionally, but at smaller military and industrial sites there may have been a more spontaneous development of such vici.

The mixture of Romano-British timber buildings and more official stone-built structures argues for a pragmatic working relationship between the Roman military, the Roman industrial team operating at Prestatyn and local metallurgists, each benefiting from the resources, skills and knowledge of the other, as well as the potentially extensive through-traffic – although whether a British copper-alloy worker ever had the opportunity to test out the joys of the bath-house is an other matter!

A Roman Road?

Information board at the site showing linkages between different sites in the Roman period. Click image to expand to read clearly.

Most of these proposals would make sense if the bath house and the related structures that must have accompanied it were on a road that connected into the road network; or that it was associated with a port, or both. The Antonine Itinerary lists a route in north Wales as Iter IX, which ran between the legionary fortresses at Chester (Roman Deva) and Caernarfon (Roman Segontium) at the crossing to Anglesey. This bypassed the north coast in favour of a more direct route, which still, however, had to skirt the Clwydian Range, nearing the coast at the northern end of the range, which would not have been too far from Prestatyn . As the CPAT report puts it:

It is assumed that a major Roman road ran the length The Vale of Clwyd, linking military sites at Caer Gai near Bala and an assumed fort in the Corwen area with sites in the neighbourhood of Ruthin and St Asaph. The course of this road and its relationship with Roman settlements and possible military activity in the vale will no doubt be discovered in the future.

The Roman fort of Canovium at Caerhun with St Mary’s Church in one corner. Copyright Mark Walters, Skywest Surveys, CC BY-NC-DD 4.0. Source: Vici.org

The route is presumed to have proceeded to the fort at Caerhun (Roman Canovium) in the Vale of Clwyd before heading towards Segontium and Anglesey. A bath house with a hypocaust was found in the Canovium fort, which was built in c.75 AD and destroyed in c.200, with tiles similarly stamped with Legio XX markings. The Antonine Itinerary’s description of Iter IX mentions a Roman way station named Varis. Although its precise location is unknown, and there were suggestions that this might have been located at Prestatyn, the most likely candidate at the moment is thought to be St Asaph. It is possible that a branch road could have connected a settlement at Prestatyn to this route, possibly at St Asaph, particularly if it was being used as a coastal port. Looking at a map, Rhyl might seem a better choice for a port, but there may have been political as well as economic reasons why Prestatyn could have been more suitable.

A Roman milestone was found at Gwaenysgor in 1956, dated to AD 231-5. The nearest known Roman road was 6km away, so it was either brought from there or an as-yet undiscovered off-shoot of that road.

The site and its objects in the 20th and 21st Centuries

The bath-house site

Although the site was opened up for excavation in 1937 and 1938, it was covered over afterwards to protect it. When planning permission was granted for the building of the housing estate, which began in the 1980s, archaeologists were allowed in to excavate, after which the site was left uncovered and preserved for visits by the general public.

Screen grab of part of Steve Howe’s Chester Walls page showing what Melyd Avenue looked like on one of his visits, as well as one of the stamped tiles in situ. Source: A Virtual Stroll Around the Walls of Chester website . Click to expand.

The modern story of the Prestatyn Roman baths as a visitor attraction is described by Steve Howe on his A Virtual Walk Around The Walls website here. Steve Howe visited in 1998, when the hypocaust was in good condition, preserving tiles stamped with the name and symbol of the 20th Legion. In subsequent visits in 2001 and 2008, Steve Howe talks about the the deterioration of the site, the absence of the stamped tiles and the general state of degradation. Writing in 2022, in County Voice (a Denbighshire County Council newsletter), Claudia Smith outlined a series of works being proposed in order to repair the site and to improve its public appeal.

At the end of the 1984-5 report, published in 1989, Blockley suggested that looking for the postulated harbour would be a logical follow-up project, in the Fforddisa area of Prestatyn, but this has not yet taken place.

In 2018 the Daily Post reported that an area of land earmarked for a housing development near Dyserth (to the south of Prestatyn) was under assessment by the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust with a view to excavating it to attempt to find the elusive section of Roman road that it is thought must have connected Prestatyn with the wider world, but I have not yet tracked down any follow-up to this story.

Artefacts

Professor Newstead describes, in his 1937 publication, how some objects remained in the private collection of Mr Smith, the discoverer of the site, and how those that Newstead himself had excavated were removed to the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. The Roman Inscriptions of Britain website mentions that many of the inscribed objects from Prestatyn were in the Prestatyn Museum, but also notes that this appears to have closed down. There is no note of where either Mr Smith’s collection or the Prestatyn Museum’s objects (perhaps one and the same) may have ended up. I cannot find a record in Kevin Blockley’s account of the 1984-84 excavations of where the artefacts from that excavation were eventually sent.

Final Comments

Although the bath-house, built in around AD 120, was small, by AD 150 it contained the three main components required for a bath-house: the hot room, warm room and cold room with plunge pool. This required two technical elements – a means of heating the two heated rooms (furnace, flues and hypocausts) and a means of channelling cold water to and from the cold room (aqueduct and drains, and possibly water tanks). A store for wood would have been required adjacent to the bath-house. The bath-house was the leisure-centre for a settlement dominated by industrial workshops, notably for the manufacture of objects made of copper-alloy (bronze).

Although the bath-house, built in around AD 120, was small, by AD 150 it contained the three main components required for a bath-house: the hot room, warm room and cold room with plunge pool. This required two technical elements – a means of heating the two heated rooms (furnace, flues and hypocausts) and a means of channelling cold water to and from the cold room (aqueduct and drains, and possibly water tanks). A store for wood would have been required adjacent to the bath-house. The bath-house was the leisure-centre for a settlement dominated by industrial workshops, notably for the manufacture of objects made of copper-alloy (bronze).

The site is a bit like a glacial erratic – something unexpected left during a substantial invasion and after a substantial retreat. There is not a great deal of Rome surviving above the ground in northeast Wales, and that gives the Prestatyn Bath House all the more kudos. As more sites are discovered and more stretches of road revealed, the picture should become clearer. In spite of neglect in the past, during which some of the stamp-marked tiles were apparently removed, it is a great little site to visit, for which details are provided below.

Visiting

As mentioned above, this is right in the middle of a small housing estate, a cul-de-sac. It is just off the A547 (Meliden Road) to Prestatyn on Melyd Avenue. Its What3Words location is ///unfocused.detective.jetting. There are two car parking spaces at the site, and a limited amount of on-road parking, but this is not a busy destination. It was nice that we were not the only people there when we arrived, and I am sure that there are occasional school trips to a local heritage celebrity, but it was a quiet visit whilst we were there.

The two information boards at the site were helpful, and each of them had a QR code. Very sadly it comes up with a “404 Page Not Found” message. Always a disappointment when this happens and a good idea to provide additional information is allowed to lapse.

Always thinking about people with unwilling legs, I would give this a thumbs-up based on my Dad’s experiences (walking with a stick due to a dodgy leg, but okay for the three steps at the site if there was an arm to lean on). There are no handrails accompanying the steps, and part of the circuit around the site was blocked by repair works.

If you are coming at it from Chester, and want a day trip, it is worth coming off the A55 at Junction 31 and taking the opportunity to visit Gop Cairn, Gop Cave (see details on the Coflein website – parking in Trelawnyd and reached via public footpath, and about which much more on a future post) and the stunning Dyserth waterfall as well, which is just a few seconds from the road (operating a 50p per person honesty payment system, with a small car park next door). Take a raincoat or hat – the spray from the waterfall is considerable and we got quite a good soaking!

There seem to be plenty of places to stop for a coffee in the villages, and we had a very good lunch at the newly renovated The Crown public house in Trelawnyd after walking up to Gop cairn and cave.

Sources

Books and papers

The site under excavation by Newstead in the 1930s. Source: Newstead 1937 (National Library of Wales)

Arnold, Christopher J. and Jeffrey L. Davies, 2000. Roman and Early Medieval Wales. Sutton Publishing

Blockley, Kevin. 1989. Prestatyn 1984-5. An Iron Age Farmstead and Romano-British Industrial Settlement in North Wales. BAR British Series 210

de la Bédoyère, Guy, 2001. The Buildings of Roman Britain. Tempus Publishing

de la Bédoyère, Guy, 1988. Samian Ware. Shire

Dark, Ken and Dark, Petra 1997. The Landscape of Roman Britain. Sutton Publishing

Mason, David J.P. 2001, 2007. Roman Chester. The City of the Eagles. Tempus Publishing

Newstead, Robert 1937. The Roman Station, Prestatyn. First Interim Report. Archaeologia Cambrensis vol.92), p.208-32

Newstead, Robert 1938. The Roman Station, Prestatyn. Second Interim Report. Archaeologia Cambrensis vol.93), p.175-91.

Websites

Coflein

Prestatyn Roman Site

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/306722?term=prestatyn%20roman%20bath%20house

Clwyd and Powys Archaeological Trust (CPAT)

Historic Landscape Characterization. The Vale of Clwyd. Transport and Communications

https://www.cpat.org.uk/projects/longer/histland/clwyd/cltransp.htm

A Virtual Walk Around the Walls of Chester

The Roman Bath House near Prestatyn, North Wales by Steve Howe

Part 1, 1998

https://chesterwalls.info/baths.html

Part 2, 2001 and 2008

https://chesterwalls.info/baths2.html

County Voice, Denbighshire County Council

The Roman Baths: A Roman Mystery in Prestatyn? December 2022

https://countyvoice.denbighshire.gov.uk/english/county-voice-december-2022/countryside-services/the-roman-baths-a-roman-mystery-in-prestatyn

Roman Britain

Caerhun (Canovium) Roman Fort

https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/canovium/

St. Asaph (Varis) Roman Settlement. Possible Roman Fort and Probable Settlement

https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/st_asaph/

Ruthin Roman Fort

https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/ruthin/

The Roads in Roman Britain

Roman Roads in Cheshire > The Roman Road from Chester to North Wales

Margary Number 67a. By David Ratledge and Neil Buckley

https://www.romanroads.org/gazetteer/cheshire/M67a.htm

Deganwy History

Roman Roads in North-West Wales. A talk by David Hopewell (Gwynedd Archaeological Trust (GAT), October 17th 2019. Written up by Lucinda Smith.

https://www.deganwyhistory.co.uk/roman-roads-in-north-west-wales/

Roman Insciptions in Britain

RIB II.2404.31-2 lead ingot found in Dee at RooDee in 1886

https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/2404.31

Leg XX VV inscriptions found in Prestatyn both at the Baths and beyond

https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/search?qv=prestatyn&submit=

Wales Live (The Daily Post)

Archaeological dig could unearth Roman road on site earmarked for new homes. October 16th 2018. By Gareth Hughes

https://www.dailypost.co.uk/news/north-wales-news/archaeological-dig-could-unearth-roman-15285372

Vindolanda Charitable trust

A closer look at Samian pottery

https://www.vindolanda.com/blog/a-closer-look-at-samian-pottery

English Heritage

Baths and Bathing in Roman Britain

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/story-of-england/romans/roman-bathing/