Introduction

Gop Hill in northeast Wales, a few miles southeast of Prestatyn, and just above the village of Trelawnyd (formerly Newmarket from 1710 to 1954) is home to Gop Cave and Gop Cairn, just a few minutes apart from one another. Gop Cairn has the distinction of being the largest man-made prehistoric mound in Wales, and when approached from a distance, its size really is impressive. Although the cairn was investigated in the 19th century, with a vertical shaft sunk from the top to the level of the floor, and a “drift” tunnelled outward from the base of the shaft, no burial chamber or human remains were found.

Gop Hill in northeast Wales, a few miles southeast of Prestatyn, and just above the village of Trelawnyd (formerly Newmarket from 1710 to 1954) is home to Gop Cave and Gop Cairn, just a few minutes apart from one another. Gop Cairn has the distinction of being the largest man-made prehistoric mound in Wales, and when approached from a distance, its size really is impressive. Although the cairn was investigated in the 19th century, with a vertical shaft sunk from the top to the level of the floor, and a “drift” tunnelled outward from the base of the shaft, no burial chamber or human remains were found.

The south-facing limestone cave was also investigated, producing Pleistocene zoological remains, Mesolithic stone tools and Neolithic human burials and contemporary artefacts and the bones of both domesticated and wild animals. In 1868 Boyd Dawkins excavated pre-glacial animal species such as woolly rhino and steppe bison in the cave deposits, which provided significant data about local ecological conditions. Excavations by T. Allen Glenn in the early 1920s discovered Mesolithic remains on the platform outside the cave. Although this was a small assemblage, it is an important contributor of knowledge about the poorly understood North Wales Mesolithic. The Boyd Dawkins excavations also produced an unusual and very important Neolithic burial chamber. It was found in one of the upper layers, with walls made of layers of stone containing at least 14 burials. Pottery and stone tools found with them were sufficiently distinctive to provide a chronological range, placing the burials within the Neolithic period. Excavations conducted by John H. Morris and T.A. Glenn between 1908 and 1914 found another six burials in a previously undiscovered passageway, including two children as well as a Neolithic axe-head from the nearby Graig Lywyd axe factory and are considered to lie within the same date range as those found by Boyd Dawkins, taking the total count of individuals found up to 20. It did not take a great leap of imagination to speculate that the Neolithic date for the cave could suggest a similar date for the cairn, although this remains unverified.

The south-facing limestone cave was also investigated, producing Pleistocene zoological remains, Mesolithic stone tools and Neolithic human burials and contemporary artefacts and the bones of both domesticated and wild animals. In 1868 Boyd Dawkins excavated pre-glacial animal species such as woolly rhino and steppe bison in the cave deposits, which provided significant data about local ecological conditions. Excavations by T. Allen Glenn in the early 1920s discovered Mesolithic remains on the platform outside the cave. Although this was a small assemblage, it is an important contributor of knowledge about the poorly understood North Wales Mesolithic. The Boyd Dawkins excavations also produced an unusual and very important Neolithic burial chamber. It was found in one of the upper layers, with walls made of layers of stone containing at least 14 burials. Pottery and stone tools found with them were sufficiently distinctive to provide a chronological range, placing the burials within the Neolithic period. Excavations conducted by John H. Morris and T.A. Glenn between 1908 and 1914 found another six burials in a previously undiscovered passageway, including two children as well as a Neolithic axe-head from the nearby Graig Lywyd axe factory and are considered to lie within the same date range as those found by Boyd Dawkins, taking the total count of individuals found up to 20. It did not take a great leap of imagination to speculate that the Neolithic date for the cave could suggest a similar date for the cairn, although this remains unverified.

Plan of Gop Cave. Source: Cambrian Caving Council Survey 2013 (Cris Ebbs)

Over three posts, the Gop Hill sites are described and the work carried out summarized. This post, Part 1, looks at the 19th century excavation of Gop Cave by Sir William Boyd Dawkins, a really rather remarkable early investigator of prehistoric habitats and fauna as well as archaeological remains. Visiting details are provided towards the end of Part 1, after which there is a list of references. Part 2 looks in detail at the Neolithic burial within the cave, and part 3 looks at the cairn.

Sir William Boyd Dawkins, excavating 1886-1887

When I was working in caves with archaeological deposits in the mid- to late-1980s, 100 years after William Boyd Dawkins was excavating at Gop Cave, he was a very well-known name, and a respected one. It is easy to be frustrated with the quality of the work carried out in those early investigations, some of which were far from systematic, and caves have some particular quirks of their own to contend with, but a few of these early investigators were impressive and Sir William Boyd Dawkins was one of them.

Born near Welshpool in 1837 Sir Wiliam Boyd Dawkins (1837-1929), developed a keen interest as a child in collecting fossils. His initial field of interest was primarily geology, natural history and palaeontology, all of which have in common with archaeology a focus on stratified sequences and the relative positioning of fossils, bones and objects within those sequences. Just as early archaeologists were interested in building up sequences of artefacts so that they could understand how human technology developed, early palaeontologists were interested in the developmental sequence of prehistoric animal and plant species. In 1860 he graduated in Natural Sciences and Classics from Oxford and in 1861 he was appointed to the Geological Survey of Great Britain. Fortunately, because Sir William found many archaeological remains during his investigations, he treated these more recent discoveries with equal interest and respect. His earliest archaeological excavations were at Wookey Hole in Somerset where he discovered some of the first evidence of Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) occupation. These discoveries helped him to develop methodologies for excavating cave sites and to build up a good understanding of the type of environmental and human data that he was likely to encounter within particular geological and geomorphological contexts. He wrote a number of important articles about extinct sub-species of rhinoceros that had once inhabited Britain. He became the first President of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society and President of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. He excavated at a number of cave sites in north Wales.

Born near Welshpool in 1837 Sir Wiliam Boyd Dawkins (1837-1929), developed a keen interest as a child in collecting fossils. His initial field of interest was primarily geology, natural history and palaeontology, all of which have in common with archaeology a focus on stratified sequences and the relative positioning of fossils, bones and objects within those sequences. Just as early archaeologists were interested in building up sequences of artefacts so that they could understand how human technology developed, early palaeontologists were interested in the developmental sequence of prehistoric animal and plant species. In 1860 he graduated in Natural Sciences and Classics from Oxford and in 1861 he was appointed to the Geological Survey of Great Britain. Fortunately, because Sir William found many archaeological remains during his investigations, he treated these more recent discoveries with equal interest and respect. His earliest archaeological excavations were at Wookey Hole in Somerset where he discovered some of the first evidence of Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) occupation. These discoveries helped him to develop methodologies for excavating cave sites and to build up a good understanding of the type of environmental and human data that he was likely to encounter within particular geological and geomorphological contexts. He wrote a number of important articles about extinct sub-species of rhinoceros that had once inhabited Britain. He became the first President of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society and President of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. He excavated at a number of cave sites in north Wales.

The four phases of Gop Cave deposits

When Boyd Dawkins first encountered Gop Cave, it was full to the brim with glacial, post-glacial and more recent debris and rock fall:

While the cairn was being explored my attention was attracted to a fox-earth at the base of a low scarp of limestone 141 feet to the south-west of the cairn. It occupied a position which I have almost invariably found to indicate the presence of a cavern used by foxes, badgers, and rabbits as a place for shelter. I therefore resolved to explore this, with the assistance of Mr. P. G. Pochin. The fox-earth led us into a cave completely blocked up at the entrance by earth and stones and large masses of limestone, which had fallen from the ledge of rock above. This accumulation of debris occupied a space 19 feet in width, and extended along the whole front of the cavern

Nothing loth, he set about clearing it in a top-down methodical way that would allow him to assess the chronological composition of the deposits. It was a remarkable achievement, given the incredibly limited head space and the absence of more than a thin envelope of natural light.

Figure 4 showing the excavations of the cave in horizontal plan, with the sections through the deposits both outside and within the cave. Feature B is the Neolithic burial chamber. Source: Boyd Dawkins 1901, p.325

Boyd Dawkins identified four distinct phases within the cave. These are shown in the table below and discussed beneath. The terms Pleistocene and Holocene used in the table below refer to consecutive periods in the geological timescale. The Pleistocene begins at around , when the last glacier retreated and the planet entered its present inter-glacial phase, the Holocene. The Holocene levels at Gop Cave, which include the 14 burials (thought by Boyd Dawkins to be Bronze Age but now reassigned to the earlier Neolithic), will be discussed in Part 2. Below is a discussion of the Pleistocene levels.

Geological Table Source: USGS

Boyd Dawkins noted that the layers were not as they would have been originally deposited: “They appear to have been washed out of the original hyaena floors by the action of water, and to have been redeposited at a time later than the occupation of the cave by hyaenas.” The presence of stone of non-local origin also argues for different phases of water and glacial activity entering the cave, scouring the deposits and replacing them.

Boy Dawkins identified the Pleistocene fauna from the surviving bones and antlers found in the cave as follows.

- Cave hyaena – Hycena spelaea

- Bison – Bison priscus

- Red deer – Cervus elaphus

- Reindeer – Cervus tarandus

- Roe deer – Cervus capreolus

- Horse – Equus caballus

- Woolly rhinoceros – Rhinoceros tichorhinus

Woolly Rhino. Source: Science

Woolly rhino (now designated Coelodonta antiquitatis), cave hyaena (now referred to as Crocuta crocuta , and sometimes Crocuta crocuta spelaea) and Bison priscus (steppe bison) are now extinct. The steppe bison was the species painted in famous Upper Palaeolithic caves like Lascaux in France and Altamira in France. Although Boyd Dawkins identified horse as Equus caballus, if the identification of horse was correct, it would probably have been the wild ancestor of caballus, Equus ferus. Reindeer are no longer found wild in Britain. Of the species on his list, red deer and roe deer and horse are the only wild species that remain in Britain. Boyd Dawkins observed that some of the remains, and particularly the antlers of “the reindeer, bore the teeth marks of hyaenas, and had evidently belonged to animals which had fallen victims to those bone-eating carnivores.”

20th Century Excavations

Further excavations took place during the earlier part of the 20th Century, contributing more information.

Between 1908 and 1914 John H. Morris and T. Allen Glenn investigated the northwest passage of the cave system, sometimes. This was missed by Boyd Dawkins because it was hidden behind a blockage of clay and stalagmite. This passage produced an additional six skeletons, two of which were children. Glenn describes an excavation “carried out with extreme care and by modern methods” but says that due to burrowing animals there was no recognizable stratification byond determining Pleistocene and Neolithic levels. The floor was covered to a depth of between 18 inches and 2ft “with cave earth and pieces of limestone over a hard floor of clay mixed with stalactite fragments and limestone rubble” over bedrock. There is some indication that limestone slabs had been used to build low walls around some of these skeletons. Finds within the cave, at the new entrance and near the cave between 1911 and 1917 were collected by Morris. Neolithic human remains and artefacts were found, and will be discussed in Part 2. Animal remains found were horse, sheep/goat, ox, pig, wolf, fox, bear, lynx, badger, fowl, hare, rabbit, frog, watervole, mole, stoat and fieldmouse. The mixture of Pleistocene and Holocene species suggests that these were highly disturbed layers, probably due to the activity of burrowing animals mentioned by Allen.

The excavations linked the passage in which they were working to the second entrance, the very small opening for which is a little further along the ridge to the west, and shown on the plan at the top of this post. This is sometimes referred to as the North-West Cave, although it is part of the same cave system as the main Gop Cave.

T. Allen Glenn returned to the site between 1920 and 1921, funded by the National Museum of Wales. He excavated the platform in front of the cave, which was largely untouched by Boyd Dawkins and found more human and animal remains, as well as Mesolithic stone tools, described below. Glenn wrote up both his own and Morris’s excavations in one 1935 report.

In 1956 William H. Stead excavated at the site and amongst other animal remains found a lion tibia. The reports are in the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, nos 23 (1957), 28 (1958) and 29 (1960). Although I have listed them in the bibliography, I don’t have access online via the University of Chester, and the library does not have these volumes on the shelves, so I have been unable to read up on the findings. If I get hold of them (please give me a yell if you have access to them!), I’ll update this section.

Dating the animal remains in the Pleistocene cave

There were only certain periods when Britain was actually habitable. One reason is that harsh climatic conditions during glacial periods forced most life to leave all but the most southern areas. For example, between c.160,00 and 80, 000 years ago the environment was too hostile for human occupation and for most animals. Another reason is that, after 130,000 years ago the permanent chalk land-bridge between Britain and Europe was destroyed, and after this time Britain and Europe were only connected during glacial periods when the water level dropped sufficiently for land-bridges to be revealed, which enabled animal and human migratory movement. Modern research into the climatic and environmental past has helped to clarify when land bridges between Europe and Britain enabled animals and humans to wander freely. With the final retreat of the ice sheets at around 10,000 BC the land bridges were permanently submerged. De Groote et al explain this very clearly:

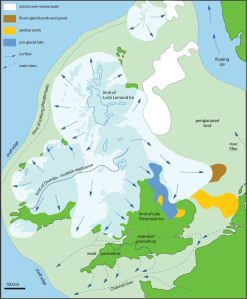

Generalised reconstruction of the land surface and the extent of ice sheets of the British Isles. Source: De Groote et al 2017, fig.1 p.3

From the early Pleistocene, Britain was connected to main-land Europe by a land-bridge that enabled humans and fauna to migrate in and out (Fig. 1A). Until about 130,000 years ago, this narrow chalk isthmus, separating the north (North Sea) and southwest (English Channel) marine embayments, kept Britain connected to varying extents even when sea-levels were high during the warm interglacial periods; the eventual complete breaching of this chalk barrier was crucial in forming the island and the Dover Strait. During glacial periods, much of the earth’s water would have been trapped in the ice caps and when, during the later Pleistocene, the bed of the North Sea was exposed, a large land area known as Doggerland, created by geological uplift and sedimentation from rivers, also provided a route into the British Isles and fauna, including hominins, would have entered this way. The flooding of the shallow shelf areas of the English Channel and the North Sea are the consequence of the current high interglacial sea levels.

Even without modern scientific dating methods, reliable time-ranges can be assigned to animal bone assemblages on the basis of which species were found together in a certain place during a certain period. Boyd Dawkins had already assembled a considerable amount of data on the subject, some of which was published in his earlier work Early Man in Britain published in 1880.

AHOB time chart showing periods of human absence and occupation. Click to enlarge or see original on the AHOB website

Improvements in palaeo-zoology have helped to clarify which species were present during which periods. Some animals that are now either completely extinct or permanently migrated out of Britain provide a latest possible date for their presence. Studies of prehistoric assemblages of fauna have also helped to fix date ranges for the presence of certain species, assigning them to marine isotope stages (also known as oxygen isotope stages). Marine isotope stages measure oxygen isotopes in sea water that is absorbed into the skeletons of tiny single-celled organisms called foraminifera, which are preserved in sediments on the sea floor. The oxygen isotopes contain information about the volume of ice present globally, and therefore provide a record of alternating glacial and interglacial periods. The faunal assemblage corresponds well to MIS 3, which falls into the Middle Palaeolithic archaeological period. Woolly rhino, for example, had left Britain by around 30,000 years ago. The entire assemblage probably puts Gop Cave in Marine isotope stage 3 (MIS 3). MIS 3 lasts from between 60,000 and 25,000 years ago. The conditions were ideal for woolly rhinoceros, horse, bison, hyaena, and reindeer, which inhabited temperate but cold semi-arid steppe-like conditions with often hot summers and very cold winters. Steppes are characterized by wide open treeless grasslands, with small shrubs, ideal for grazing species, and for carnivores preying on the grass-loving herbivores.

Pontnewydd Cave entrance. Source: National Museum of Wales

Even though the idea of woolly rhino, bison and hyaena roaming the hills of north Wales, all of them now extinct, may seem distinctly exotic, these time ranges are not particularly early for Britain. Not far away, near St Asaph, the cave site of Pontnewydd produced stone tools and human remains in association with animal species for which sound scientific dates were obtained during modern excavations. The human remains found in association with stone tools belonged to the branch of hominid known as Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis, named for the type site in the Neander Valley in Germany) and the dates cluster around 225,000 years ago. If correct, the Gop Cave date ranges are relatively recent by comparison.

Although MIS 3 corresponds to periods of human occupation in Britain during the Middle Palaeolithic there was no human habitation identified within the Pleistocene levels of the cave. Boyd Dawkins was experienced at identifying human artefacts and would almost certainly have recognized them had any been there to be found. a number of brief occupations of the country, Britain would have been occupied intermittently during this time, depending on the environmental conditions, and probably only by small groups. The most probably candidate for any humans dodging lions and woolly rhinos and competing with hyaenas for dining on deer, may have been Homo Neanderthalensis (Neanderthals). The oldest Neanderthal find in Britain was from Swanscombe in Kent, where a skull dates to c.400,000 years ago, a warm interglacial period. Neanderthals left and re-entered Britain numerous times, their movements determined by glacial and interglacial conditions, until around 40,000 years ago when the Neanderthals became extinct.

The Mesolithic

The Mesolithic, corresponding to the geological Holocene, represents settlement during the earliest post-glacial period. Although the site was small, the Gop artefacts are very typical of Mesolithic finds in the area. The stone tools found included 6 microliths (tiny stone tools usually 3cm or less long), a scraper, two other tools of undetermined types, possibly waste flakes, and twenty three microlith and blade cores. A core is the original piece of stone after it has been worked. When microliths, flakes and blades have been struck from it it is discarded, but still bears the marks of the tools that were removed from it. Of the microliths, Geoffrey Wainwright describes two were obliquely blunted, two lanceolate, and four scalene triangles. There was also one broad point retouched on both sides and a section of a bone pin.

Distribution of Mesolithic sites in Wales. Source: Heneb Dyfed

The earliest known Mesolithic site in Wales dates to c.8600 BC (some 10,500 years ago) at The Nab Head in southwest Wales (no.5 on the map to the right). In 2021 a 9000 year old site was found on Castle Hill, off Hylas Lane in Rhuddlan, where over 13,000 stone tools and five decorated stone pebbles were found. Another well known site is at Trwyn Du on Anglesey where a Mesolithic occupation dates to between 8,000- 9,000 years ago, and was preserved beneath Bronze Age burial mound excavated when it was threatened by coastal erosion in 1974 (no.9 on the map).

With the withdrawal of the ice sheets, vegetation re-established itself, and whilst the land-bridge remained in tact, animals once again drifted across the land, with humans in their wake. Once the ice had fully retreated, the land-bridge was submerged and Britain and Ireland became separated both from the continent and from each other. The island was soon occupied by many small groups exploiting inland and coastal resources, hunting, collecting plant resources, fishing and collecting shellfish.

Decorated stone pebble from the Mesolithic deposits at Rhuddlan. Source: Dyfed Archaeology

Warmer and wetter than today, with a deciduous woodland landscape, the environment favoured different wild animal populations from the pre-glacial period, which required different hunting techniques. Particularly characteristic of the Mesolithic toolkit was the microlith, a catch-all term for a large number of varieties of tiny stone artefact that could have been hafted into wood, bone or antler to make arrows, spears, harpoons and scythes. Many Mesolithic communities were located on or near the the seashore. The seashore was a movable feast at this time as a) the ice continued to melt, raising sea levels, and b) land, which had been compressed under the pressure of the ice, began to rise. The exploitation of marine resources included both fish and shellfish. It was these settlers who, stranded on an island when the land-bridge was lost, were sufficiently stable and persistent to contribute to modern DNA.

Although permanent amelioration of the climate provided the ability to develop new patterns of living eventually lead to the expansion of populations and the modification of landscape, sites are difficult to locate, some were submerged during rising sea levels, and many are often highly disturbed, meaning that the period is still poorly understood. Each new site therefore contributes important data to the overall picture, and Gop Cave contributes information about where such sites were to be found in north Wales and what sort of activities were pursued.

The location of the finds today

Davies, writing in 1949, says that most of the animal and human bones from the Dawkins excavations were stored at the pigeon house belonging to Gop Farm, but that some of these were sold in around 1912 to an archaeologist in Wrexham. Davies himself saw “great quantities of bone” in the pigeon house in 1913 but in the same year, although T. Allen Glenn, who had excavated at the cave, had received permission from the estate manager to remove the archaeological remains, the tenant threw all of it “down an open mine-shaft nearby.” He goes on: “In a letter dated, ‘The Manchester museum, The University, Nov.19, 1937,’ the keeper, Mr. R.U. Sayce, M.A., supplied the information that there were in the museum several of the remains from the cave; they included animal bones, human skulls, and limb bones; also some sherds of Neolithic ‘B’ pottery. The long flint implement and the Kimmeridge clay links have not been traced.” The pottery, the flint implement and the Kimmeridge objects relate to the cairn and will be discussed in part 2. Davies also says that the finds from the objects retained by Morris at his home in Rhyl (where Davies was able to inspect them) were bequeathed to the National Museum of Wales. Those from the subsequent Glenn excavations in 1920-21 were also deposited in the National Museum of Wales, who had funded Glenn’s work.

According to Cris Ebbs, on the Cambrian Caving Council website, other zoological and archaeological remains that were not disposed of are now in the collections of Aura Museums Service, Grosvenor Museum in Chester.

Conclusions

Although there were no human remains in the Pleistocene levels of Gop Cave, the faunal remains provide a fascinating insight of their own into the environmental conditions of north Wales, suggesting that a steppe environment prevailed, possibly at some stage between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago. Understanding of the palaeozoology, palaeoecoloy and archaeology of the Pleistocene are all dependent on the work of palaeanthropologists, geologists, geomorphologists and climatologists, and many other specialists, all contributing very specialized research about how and when animals and humans would have been able to migrate to and from what is today an island.

Although there were no human remains in the Pleistocene levels of Gop Cave, the faunal remains provide a fascinating insight of their own into the environmental conditions of north Wales, suggesting that a steppe environment prevailed, possibly at some stage between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago. Understanding of the palaeozoology, palaeoecoloy and archaeology of the Pleistocene are all dependent on the work of palaeanthropologists, geologists, geomorphologists and climatologists, and many other specialists, all contributing very specialized research about how and when animals and humans would have been able to migrate to and from what is today an island.

The Mesolithic remains are the earliest evidence of human settlement in the immediate vicinity of the cave. Although they represent a small group of people probably passing through, with no signs of seasonal returns to the site, this helps to contribute to the fragmentary picture of what was happening in Wales in the post-glacial period. Both tools and tool cores were found, suggesting that tools were manufactured during the short stay at the site.

Visiting Details

When packing your rucksack or stuffing your pockets, do be sure to take a torch with a good, strong beam, and wear some solid footwear that will cope both with slippery mud and some very irregular stones and sharp rocks underfoot in the cave itself. Caves are nearly always dripping with water, so unless it has been a very dry period, you may want to have a waterproof ready to drag on. You cannot stand upright in the entrance of the cave, so you enter bent over, but it does open out so that you can explore some of the cave upright. It is a good idea to get a sense of the internal plan before you go, because the dark is very disorientating and it is quite difficult to make out what is where.

When packing your rucksack or stuffing your pockets, do be sure to take a torch with a good, strong beam, and wear some solid footwear that will cope both with slippery mud and some very irregular stones and sharp rocks underfoot in the cave itself. Caves are nearly always dripping with water, so unless it has been a very dry period, you may want to have a waterproof ready to drag on. You cannot stand upright in the entrance of the cave, so you enter bent over, but it does open out so that you can explore some of the cave upright. It is a good idea to get a sense of the internal plan before you go, because the dark is very disorientating and it is quite difficult to make out what is where.

The village of Trelawnyd showing the locations of the car park (red rectangle), and the small lane that leads to the footpath (red arrow). Click to expand. Courtesy Apple Maps.

Gop Cave is a short walk from the village of Trelawnyd on the A5151 (itself a short drive from junction 31 on the A55). It is a two-for-one scenario, as immediately above Gop Cave and only a minute or two away, and visible for miles around, is Gop Cairn. I forgot to to take a What3Words reading for the cave, but the cairn is at ///searcher.sprint.wins, Both are on public footpaths and are free of charge to access. There is a car park on the little High Street in Trelawnyd, just off the A5151, or there is a limited amount of on-street parking a bit closer to the start of the small lane that leads to the footpath on the hillside, just up the slope from the car park. The footpath is clearly marked, as shown in the photograph below.

The first part of the footpath is a small lane that takes you past a couple of houses, until it reaches a narrow path that makes its way along the side of a tall garden fence to your right. This turns abruptly right and slightly uphill, leading to a low stone-built stile which takes you on to the hillside. I was with Helen Anderson (well-known on Twitter as @Helenus_) and we were busy nattering and wild-flower spotting (complete with wild orchids) so weren’t paying too much attention to the pathway markers, but they are there if you keep an eye open.

The first part of the footpath is a small lane that takes you past a couple of houses, until it reaches a narrow path that makes its way along the side of a tall garden fence to your right. This turns abruptly right and slightly uphill, leading to a low stone-built stile which takes you on to the hillside. I was with Helen Anderson (well-known on Twitter as @Helenus_) and we were busy nattering and wild-flower spotting (complete with wild orchids) so weren’t paying too much attention to the pathway markers, but they are there if you keep an eye open.

We followed the well-worn track, which leads at this time of year, late April / early May, through bright yellow gorse until it opens onto higher ground, which is completely open, with stunning views over the surrounding valley to Iron Age hillforts on the Clwydian range and to the sea to the west. You need to turn left beneath a shallow pale grey limestone ridge to reach the main cave entrance. A very tiny secondary entrance is a little further along. Retrace your steps to go up to the cairn, through a gate in a drystone wall. For anyone wanting to stop for a breather, there’s a bench near the gate, somewhat bizarrely looking like an escapee from a Victorian arcade or promenade.

We followed the well-worn track, which leads at this time of year, late April / early May, through bright yellow gorse until it opens onto higher ground, which is completely open, with stunning views over the surrounding valley to Iron Age hillforts on the Clwydian range and to the sea to the west. You need to turn left beneath a shallow pale grey limestone ridge to reach the main cave entrance. A very tiny secondary entrance is a little further along. Retrace your steps to go up to the cairn, through a gate in a drystone wall. For anyone wanting to stop for a breather, there’s a bench near the gate, somewhat bizarrely looking like an escapee from a Victorian arcade or promenade.

Although the walk is slightly steep for a short section, it is a mellow walk, and far from strenuous and there are some great views across the valley. It took perhaps 10 minutes from the road to the cave, 15 minutes maximum, and another five minutes or so from the cave to the cairn. The cave itself requires you to duck down and be very careful both to watch your footing on a very uneven and rocky surface, and to mind your head. Best to leave your rucksack outside after liberating your torch.

If you are interested in the Iron Age heritage of the Clwydian Range, Moel Hiraddug is beautifully clear to the southwest, and other hillforts of the Clwydian Range, fading into the distance when we were there, are easily visible on a clear day,

The wildflowers were an added bonus, with a classical karst mix of tiny hardy species clinging to the almost non-existent topsoil above the limestone bedrock, including some really pretty succulents and lichens. The Early Purple Orchids (Orchis mascula) were a particular bonus, and apparently fairly common in early spring in the general area. As well as the miniature slipper-orchid shaped flowers clustering at the top of the stems, their long pointed green leaves often have dark aubergine-coloured spots along them. Read more about them on the Woodland Trust website.

The wildflowers were an added bonus, with a classical karst mix of tiny hardy species clinging to the almost non-existent topsoil above the limestone bedrock, including some really pretty succulents and lichens. The Early Purple Orchids (Orchis mascula) were a particular bonus, and apparently fairly common in early spring in the general area. As well as the miniature slipper-orchid shaped flowers clustering at the top of the stems, their long pointed green leaves often have dark aubergine-coloured spots along them. Read more about them on the Woodland Trust website.

Having visited, there’s the option of a very good lunch at The Crown Inn in Trelawnyd, which was filling up rapidly during our visit. After lunch we went on to see the gorgeous Dyserth waterfall only a few miles away, which is very close to the road (a 50p honesty fee was required for access), and then went on to visit the small but fascinating Prestatyn Roman bath-house, which was again nearby. I have posted about the bath-house here.

If you want to incorporate Gop Hill into a much longer walk (4-7 hours over 5miles / 10.5 kilometers) the Clwyd and Powys Archaeologial Trust has published what looks like an excellent one: https://www.cpat.org.uk/walks/gopcairn.pdf

Sources for parts 1 – 3

Books and Papers

N.B. The reports by Stead and Bridgewood in the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society are highlighted in green because although they are the record of the 1950s excavations, I have been unable to get access to them so I have not actually used them in this post. I have included them for the sake of completeness. If you do have access to them and don’t mind scanning them, I’d be really grateful so that I can add them to the post!

Barton, Nicholas 1997. Stone Age Britain. English Heritage / B.T, Batsford.

Barton, Nicholas 1997. Stone Age Britain. English Heritage / B.T, Batsford.

Brace, Selina, et al 2019. Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain – Supplementary Material. Nature Ecology and Evolution

https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/sites/reich.hms.harvard.edu/files/inline-files/2019_Brace_NatureEcologyEvolution_Supplement.pdf

Brady, James E. and Wendy Ashmore 1999. Mountains, Caves and Water: Ideational Landscapes of the Ancient Maya. In (eds.) Wendy Ashmore and A. Bernard Knapp. Archaeologies of Landscape. Contemporary Perspectives. Blackwell Publishers.,. p.124-145

Britnell, William J. 1991. The Neolithic. In (eds.) John Manley, Stephen Grenter and Fiona Gale. The Archaeology of Clwyd, 9.55-64

Brown, Ian. 2004. Discovering a Welsh Landscape. Archaeology in the Clwydian Range. Windgather Press

Burrow, Steve. 2011. Shadowland. Wales 3000-1500BC. Oxbow / National Museum of Wales

Crumley, Carole, L. 1999. Sacred Landscapes: Constructed and Conceptualized. In (eds.) Wendy Ashmore and A. Bernard Knapp. Archaeologies of Landscape. Contemporary Perspectives. Blackwell Publishers., p.269-276

Davies, Ellis. 1925. Hut circles and ossiferous cave on Gop Farm, Gwaunysgor, Flintshire. Archaeologia Cambrensis, 7th series, vol.5, p.436-438

Davies, Ellis 1949. The Prehistoric and Roman Remains of Flintshire with a Shotr Appendix to “The Prehistoric and Roman Remains of Denbighshire” (1929). Cardiff

Dawkins, Sir William Boyd 1874. Cave hunting, researches on the evidence of caves respecting the early inhabitants of Europe. Macmillan

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52424/52424-h/52424-h.htm

Dawkins, Sir William Boyd 1886. Early Man in Britain. Macmillan

Dawkins, Sir William Boyd 1901. On the Cairn and Sepulchral Cave at Gop, near Prestatyn. Archaeological Journal, Vol.58, vol.1

Dawkins, Sir William Boyd 1901. On the Cairn and Sepulchral Cave at Gop, near Prestatyn. Archaeological Journal, Vol.58, vol.1

De Groote, I., Lewis, M. & Stringer, C. 2017. Prehistory of the British Isles: A tale of coming and going. Bulletins et mémoires de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13219-017-0187-8

Dinnis, R. & Cris Ebbs. 2013. Cave deposits of North Wales: some comments on their archaeological importance and an inventory of sites of potential interest. Cave and Karst Science 40(1): 28-34.

https://www.academia.edu/5157200/Dinnis_R_and_Ebbs_C_2013_Cave_deposits_of_North_Wales_some_comments_on_their_archaeological_importance_and_an_inventory_of_sites_of_potential_interest_Cave_and_Karst_Science_40_1_28_34

Glenn, T. Allen, 1925. Distribution of the Graig Lwyd Axe and its Associated Cultures. Archaeologia Cambrensis vol 90, p.190-218

Jenkinson, Rogan D.S. 2023. A North-Western Habitat: the Paleoethology and Colonisation of a European Peninsula. Internet Archaeology 61

https://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue61/1/full-text.html

Lynch, Frances 2000. The Earlier Neolithic. In (eds) Frances Lynch and Stephen Aldhous-Green. Prehistoric Wales, Sutton Publishing, p.42-78

Marsolier-Kergoat M-C, Palacio P, Berthonaud V, Maksud F, Stafford T, Bégouën R, et al. 2015. Hunting the Extinct Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) Mitochondrial Genome in the Trois-Frères Paleolithic Painted Cave. PLoS ONE 10(6)

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0128267

Parker-Person, Mike 1999, 2000. The Archaeology of Death and Burial. Texas A&M University Press

Ray, Keith and Julian Thomas. 2018. Neolithic Britain. The Transformation of Social Worlds. Oxford University Press

Shanks, Michael and Christopher Tilley 1982. Ideology, symbolic power and ritual communication: a reinterpretation of Neolithic mortuary practices. In (ed.) Ian Hodder, Symbolic and Structural Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, p.129-50

Sheriden, J.A. and Davis, M. 1998. The Welsh Jest Set in Prehistory: A case of keeping up with the Joneses? In (eds.) Gibson, Alex and Derek Simpson. Prehistoric Ritual and Religion. Sutton Publishing, p.148-162.

Stead, W.H., and Bridgewood, R., 1957. Gop Cave, Newmarket and Nant-y-fuach,

Dyserth, Flintshire, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 23, p.228

Stead, W.H., and Bridgewood, R., 1958. Gop Cave, Newmarket and Nant-y-fuach,

Dyserth, Flintshire, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 24, p.219

Stead, W.H., and Bridgewood, R., 1959. Gop Cave, Newmarket and Nant-y-fuach,

Dyserth, Flintshire, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 25, p.280

Tilley, Christopher 2004. The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology: 1. Berg

Wainwright, Geoffrey J. 1961

The Mesolithic Period in South and Western Britain. Unpublished PhD, UCL April 1961

Volume 1

https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1317731/1/282048_Vol_1.pdf

Volume 2

https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1317731/2/282048_Vol_2.pdf

Westbury, Michael V. et al. 2020. Hyena paleogenomes reveal a complex evolutionary history of cross-continental gene flow between spotted and cave hyena. Science. Vol.6, No.11.

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aay0456

White, Mark J. and Paul B. Pettitt 2011. The British Late Middle Palaeolithic: An Interpretative Synthesis of Neanderthal Occupation at the Northwest Edge of the Pleistocene World. Journal of World Prehistory 24, p.25-97

Wymer, John. (ed.) 1977. Gazetteer of Mesolithic Sites in England and Wales. CBA Research Report no.20. GeoAbstracts and The Council for British Archaeology.

Websites

Ancient Human Occupation of Britain

https://ahobproject.org/

Archaeology Data Service

A database of Mesolithic Sites based on Wymer JJ and CJ Bonsall, 1977

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/mesgaz_ma_2008/

Cambrian Caving Council

Gop Cave by Cris Ebbs. Based on “An Introduction to the Caves of Northeast Wales (2000, ISBN 0 9522242 1 6)) by Cris Ebbs, which is no longer available.

https://www.cambriancavingcouncil.org.uk/registry/CoNW/CoNW_04.htm#Gop

Dafyd Archaeology (Heneb)

Mesolithic

https://www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk/wp/mesolithic-main-page/

Derbyshire County Council

William Boyd Dawkins – Chronology

https://www.derbyshire.gov.uk/site-elements/documents/pdf/leisure/buxton-museum/permanent-collections/dawkins-jackson/sir-william-boyd-dawkins/william-boyd-dawkins-chronology.pdf

Dictionary of Welsh Biography

Sir William Boyd Dawkins

https://biography.wales/article/s-DAWK-BOY-1837

Dyfed Archaeology

Mesolithic Wales

https://www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk/lostlandscapes/trwyndu.html

A Maritime Archaeological Research Agenda for England

The Mesolithic. By Martin Bell and Graeme Warren with Hannah Cobb, Simon Fitch, Antony J Long, Garry Momber, Rick J Schulting, Penny Spikins, and Fraser Sturt

https://researchframeworks.org/maritime/the-mesolithic/

Natural History Museum

First Britons

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/first-britons.html

Nation Cymru

Unearthed 9,000 year-old encampment ‘on a par with the oldest mesolithic site’ in Wales. By Jez Hemming, 17th February 2021

https://nation.cymru/news/unearthed-9000-year-old-encampment-on-a-par-with-the-oldest-mesolithic-site-in-wales/

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales

Key Sites: Northeast Wales – Palaeolithic and Mesolithic 22/12/2003

https://www.archaeoleg.org.uk/pdf/paleolithic/KEY%20SITES%20NE%20WALES%20PALAEOLITHIC%20AND%20MESOLITHIC.pdf

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales: Palaeolithic and Mesolithic, version 04 – October 2022. By Dr Elizabeth A. Walker, (Co-ordinator), Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

https://www.archaeoleg.org.uk/pdf/review2024/VERSION%2004%20Palaeolithic%20and%20Mesolithic.pdf

Science

The Rise of the Woolly Rhino. New fossil discoveries may explain origin of several Ice Age creatures. 1st September 2011, by Sid Perkins.

https://www.science.org/content/article/rise-woolly-rhino

Smithsonian Magazine

An Evolutionary Timeline of Homo Sapiens

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/essential-timeline-understanding-evolution-homo-sapiens-180976807/

South Yorkshire Historic Environment Research Framework

Palaeolithic. By Paul Pettitt

https://researchframeworks.org/syrf/palaeolithic/

Mesolithic. By Penny Spikins with a contribution by Ellen Simmons

https://researchframeworks.org/syrf/mesolithic/

UCL Blogs – Research in Museums

Migration Event: When did the first humans arrive in Britain? By Josie Mills, 24th February 2019

https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/researchers-in-museums/2019/02/24/migration-event-when-did-the-first-humans-arrive-in-britain/

University of Manchester, Science and Engineering

Sir William Boyd Dawkins – An Extraordinary Study. By Joe Shervin, 28th January 2019

https://www.mub.eps.manchester.ac.uk/science-engineering/2019/01/28/sir-william-boyd-dawkins-an-extraordinary-study/