Whether the visitor is an adult or a child, the prehistoric copper mine on the Great Orme’s Head next to Llandudno in northwest Wales is one of the best days out in Wales, and not only for those with a love of prehistory. A visit carries with it a real sense of adventure and discovery, and it is an almost unique experience.

Whether the visitor is an adult or a child, the prehistoric copper mine on the Great Orme’s Head next to Llandudno in northwest Wales is one of the best days out in Wales, and not only for those with a love of prehistory. A visit carries with it a real sense of adventure and discovery, and it is an almost unique experience.

The Great Orme mines, which became one of the most successful mining operations in Bronze Age Britain, were worked at the mine-face by both adults and children. Metallurgy revolutionized many aspects of industry and society in later prehistory before the arrival of the Romans. As the use of bronze (a mixture of copper and tin) spread throughout Britain and Europe the Great Orme became part of a European network of metal distribution. Objects made with raw materials from the site were found not merely in Britain but as far away as the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland and France, indicating how important this supply of copper became be when combined with tin from southwest England to make bronze.

Some prehistoric copper mines in Britain have only been recognized in the last few decades, partly because they were worked in more recent times, disguising earlier mining operations, and partly because they do not stand out as obviously as other archaeological sites. By contrast, the most familiar Bronze Age sites in north Wales are those that stand out clearly in the landscape, including round barrows (earth mounds) and cairns (stone mounds) in their 100s. Stone circles, stone rows and menhirs (standing stones) are also found, and occasionally a lucky find will produce a settlement site. Thanks to a number of research projects, four major concentrations of copper mines have now been identified, one of which is in Ireland, two of which are in Wales, and one in northwest England. These are now adding to the body of data not merely about copper mining but about the Bronze Age as a whole. Many are still the subject of ongoing investigation.

The Great Orme. Llandudno is clearly visible where the Great Orme begins, forming a crescent, the end of which is marked by the Little Orme to the east. On the right, heading west, is the opening of the river Conwy. By Jay-Jerry. Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC_2.0_Generic.

The Great Orme mining enterprise, which operated from around 1700-900BC (Early Bronze Age to Early Iron Age), was at its busiest for a period of over 200 years between 1600 and 1400 BC (c.3600 to 3400 years ago). In order to sustain itself for that long, the mines required, as an absolute minimum: a) a food-producing economy that could sustain a large group of miners on a permanent or semi-permanent basis, b) the knowledge, technical ability, and labour to tunnel through limestone, c) the technical ability and skills to process the ore, d) a long-term supply of wood for fire-setting and furnaces, e) a market for its products, and f) the development of long-distance connections to acquire the tin that was needed to make bronze and to distribute the finished product to its purchasers. There was also certainly a requirement amongst the miners and smelters, just as there were amongst other members of society, to address their religious needs and their sense of identity. These issues will all be touched on briefly below.

This post will cover the following topics, all very briefly

Vital Statistics

Vital Statistics- The earliest British copper mining

- Discovery and excavation at the Great Orme

- Why copper and bronze?

- The geological source of the Great Orme copper

- Mining the ore

- Processing the ore

- Manufacture of copper and bronze tools

- The development of the Great Orme Copper mines over time

- The miners of the Great Orme

- The copper and bronze trade in Britain

- The end of Bronze Age copper mining in Britain

- Final comments

- Visiting

- Sources

Some of the vital statistics

Part of the opencast mines and, at the base of the steps, access into the tunnels of the underground mines

The vital statistics for the Great Orme copper mines are sufficiently eye-popping to give a sense of how remarkable the mines were during the 500 years in which they were operational. Bearing in mind that they are still under investigation, and will be for years to come, the following figures, summarized by Steve Burrow of the National Museum of Wales in 2011, are merely guidelines, as they will have shifted upwards since then. Burrow refers to the development of the bronze industry out of the beginnings of the copper industry “the first Industrial revolution,” and when you consider the figures for the Great Orme alone you can see why this claim can be made, as they represent a considerable demand for a new product.

The opencast mines were dug from above, top-down, rather than horizontally through tunnels. This left great upright remnants of hard rock behind, now rather eerily resembling some devastated dystopian city. The soft rock could be removed with simple bone picks and hand-held hammers and it is estimated that using this tools the mine eventually covered an area 55m long, 23m wide and 8m deep. It has been estimated that 28,000 tonnes of rock had been removed from it, in order to gather the copper ore it contained, before it was exhausted.

A simplified plan of the mines in 1992, before further investigations took place. Source: Burrow 2011, p.86

In the underground mines where miners tunnelled through the rock horizontally following seams of ore, 6.5km of tunnels had been investigated by 2011, with 8-10km more anticipated, and it had been discovered that the mines reached a depth of 70m over 9 separate levels. An estimated 12,600 tonnes of ore-bearing rock were removed from them (on top of that removed from the opencast mines). The illustration on the right provides an impression of how the mines were understood in 1992 and although this picture has been considerably expanded in the last 32 years, it demonstrates very nicely how the vertical shafts and horizontal tunnels were connected and how ambitious the tunneling was.

Of the tools found, over 33,00 either whole or fragmentary bone objects were found, used as picks and shovels, and over 2400 stone hand-hammers and mauls were discovered, some of which can be seen on display at the site in the Archaeology Store. The smallest of these could be hand-held, but the largest at over 20kg would have to have been incorporated into some sort of swinging device in order to smack it into the rock. See below for details of these and other tools.

The magnificence of these numbers becomes entirely plausible on a visit to the mine when something of the extent of both opencast and underground mining operations can be experienced in person.

The earliest British copper mining

Neal Johnson’s useful visual timeline of the Early Metal Age, showing how bringing together excavated data can help archaeologists to understand when and how technological, economic and social changes occurred. Source: Neal Johnson 2017, p.7, fig.2 (in Sources at the end of Part 1). Click to enlarge and read clearly.

In the 19th century Three Age system, the Stone Age is followed by the Bronze Age, which is followed in turn by the Iron Age. The Three-Age System was devised in 1836 by Christian Thomsen, Danish archaeologist and curator of the National Museum of Denmark who developed the scheme for his guidebook to the museum’s archaeology collection. The scheme was very influential, and Thomsen can be commended for attempting to make chronological sense of an archaeological record that had was poorly understood at this time. Although these are now recognized as very crude categorizations, which exclude certain vital components of material data, they continue to be used and do represent the basic chronological truth that for hundreds of thousands of years utilitarian tools were made of stone and only then, in quick succession, by copper, bronze and iron.

In more recent systems, a Copper Age, or Chalcolithic, is inserted between the Neolithic (New Stone Age) and the Early Bronze Age and as Neal Johnson’s helpful timeline above shows, a far more nuanced understanding of this period of prehistory is now possible, incorporating pottery and the soft metals gold and silver. There has also been a shift away from materials and objects towards understanding the people and the behaviours that they they help to represent. The Bronze Age itself has been subdivided into three main phases, which reflects social and economic differences as well as changes in raw material usage and tool types. Richard Bradley assigns the dates shown in the table to the right, above, to the various sub-periods of the Bronze Age, and in regional schemes these can be modified to suit local findings.

The Moel Arthur axehead hoard. Source: Frances Lynch, The Later Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age in Prehistoric Wales, p. 101, figure 3.7

Copper mining was introduced from Europe. Two possible sources are viable for its arrival in Ireland and England. One is central Europe which was a major early producer, and the other is the Atlantic coast, with Iberia a plausible source of copper working to Killarney in southwest Ireland, where the earliest Irish and Britsh mines are found. The early Ross Island copper mine was in use from around 2400BC, and is the earliest of the Irish and British copper mines, whilst Mount Gabriel was in use from around 1700BC.

Copper halberd from Tonfanau near Aberdyfi, mid-west Wales. Source: National Museum of Wales

In Wales the earliest copper objects to be found in Britain are axes, but they were not made in Wales. A broken copper axe thought to be from south Gwynedd, and a collection of three copper axes from Moel Arthur are well known examples. On the basis of metallurgical analysis they are thought to have been imported from southwest Ireland. Copper axes were modelled on stone tools but were soon followed by an entirely new form, for which no precedent in stone is known, called a halberd. It is thought that it may have been designed as a weapon, either actual or symbolic, but what is of primary interest here is that the value of copper for inventing new and special designs was being recognized at this time.

Chronology for Bronze Age mines in Britain. Source: Williams and de Veslud, 2019. Click image to enlarge to read more clearly

Dates for the Great Orme extend from c.1900 to 400 BC (Early Bronze age to Early Iron Age) but the main activity took place towards from the middle of the Early Bronze Age until towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age. The phases described by R.Alan Williams in 2019 identify a main period of activity between c.1600 and 1400BC. This “mining boom” peak coincides with the well-known Acton Park phase of metal production, first identified at Acton Park in Wrexham, which will be discussed on a future post. The decline of metal working at Great Orme began to take place between 1400 and 1300 BC. A “twilight period” lasted into the Early Iron Age. Note that that Ross Island had already gone out of use by the time the Great Orme was opened, and that many of the other Early Bronze Age mines in mid-Wales and northwest England were also coming to an end by this time. Some of the Irish mines survived into the Middle Bronze Age, but the Great Orme was he only site to continue into the Late Bronze Age.

Discovery and excavation of the Great Orme mines

Today it is recognized that Welsh copper mines are to be found concentrated in mid- and north Wales, the biggest of which were the Great Orme and Parys (Anglesey) mines, just 20 km apart. Both were exploited for copper during the 18th and 19th centuries, and it is at this time, both in Wales and at Alderley Edge in Cheshire, that the earlier mines were first recognized and recorded when the miners found that their new shafts were colliding with pre-existing ones. Antiquarian interest in some of these much earlier mine shafts resulted in some speculative reports about how old they might be.

Today it is recognized that Welsh copper mines are to be found concentrated in mid- and north Wales, the biggest of which were the Great Orme and Parys (Anglesey) mines, just 20 km apart. Both were exploited for copper during the 18th and 19th centuries, and it is at this time, both in Wales and at Alderley Edge in Cheshire, that the earlier mines were first recognized and recorded when the miners found that their new shafts were colliding with pre-existing ones. Antiquarian interest in some of these much earlier mine shafts resulted in some speculative reports about how old they might be.

In the case of the Great Orme, the first modern excavations took place in 1938-1939 when Oliver Davies, an expert on Roman mining in Europe, headed up a committee for The British Association for the Advancement of Science. The remit of the committee was to investigate early metal mining. In mid and north Wales it investigated mines on Parys (Anglesey), Cwmystwyth (Ceredigion), Nantyreira (Gwynedd) and the Great Orme’s Head. Although their attempts to date the mines assumed that they were probably “Celtic” (i.e. more recent than they actually are) the project successfully raised an awareness of prehistoric copper mining in Wales.

Archaeological excavations on the Great Orme in around 1900. Source: Peoples Collection Wales

Building on this initial research, the amateur archaeologist Duncan James carried out some excavations in the Great Orme area in the 1970s, and was able to obtain an radiocarbon date that indicated a Bronze Age date. In the 1980s Andrew Lewis for the Great Orme Exploration Society and Andrew Dutton for the Gwynedd Archaeological Trust both undertook survey and excavation work that made considerable advances in knowledge about the copper mines. Work by Simon Timberlake and the Early Mines Research Group greatly expanded knowledge of copper mining in the north- and mid-Wales area as a whole. Since the 1980s work has continued to be carried out at the Great Orme and elsewhere, and a number of post-graduate research projects, some of which are available for download on the Research page of the Great Orme official website, have focused on particular aspects of the mines and related topics. Most recently, the important PhD research undertaken by R. Alan Williams at the Great Orme was published by Archaeopress in 2023, and contains the most up to date information.

Why copper and bronze?

Before the introduction of copper, the main materials for making tools were stone, wood and bone. Whereas these were worked by reduction (knapping pieces of stone off a core or carving wood and bone to make shaped tools), copper was created by melting well-ground malachite using a pestle and mortar until it underwent a process of change, becoming molten. This was poured into a mould to cool and create an object. This is discussed further below. It was not an entirely alien production process, having something in common with kiln-fired pottery, which had been made since the Neolithic, but it was a new approach to tools-making.

Copper was not as strong or resilient as stone, and its primary value was the production of a particularly thin and very sharp blade. Although stone tools could be very sharp, it was impossible to achieve the thin edge of a cast metal. This edge was particularly useful for tree felling and branch cutting, as well as the shaping of wood. Although it would blunt quickly, because the metal was so soft, the blade could be easily sharpened after use. When damaged, it could be recast with other broken objects and used to create new tools. However, because of its softens its uses continued to be limited. In some cases, its value as a prestige item may have exceeded its value as a functional tool.

Copper came into its own when blended with 10% tin to make bronze, which represented a new world of possibility and innovation. By lowering the melting point of copper, the addition of tin made copper easier to handle and the resulting bronze was harder and stronger than copper, just as sharp, and less prone to damage. Although the earliest bronze forms copied copper objects, designs soon emerged that represented significant departures from stone and copper antecedents, including adzes, halberds, knives, pins, ornaments and in the later Bronze Age swords and shields. Like copper it could be recast and moulded into new shapes, providing them with a very long-term life cycle that outlived the lives of individual tools, conferring a particular and unique value on metal tools. Where a stone tool would be reworked so many times that it had to be discarded, and a pot once broken could not be safely mended, metal could achieve a form of eternal life. Many of the hoards of broken tools that have been found in Britain were clearly grouped together and retained in order to be recycled in this way, although others were clearly deposited in special locations for more spiritual purposes, perhaps partly because of this unique quality.

Bronze Age stone arrowheads from Merthyr Mawr Warren, Bridgend, Wales. Source: National Museum of Wales

Stone, wood and bone continued to be important in the Bronze Age. Stone tools in particular, became the heavy-duty implements that complemented the new metal equipment. Pestles and mortars continued to have an important role in the processing of cereals, pigments and ores, and small arrowheads continued to have a value in hunting during the Early Bronze Age. Bone was still used for small, thin needles and pins, and wood was still vital for hafting tools of bone and stone. In the longer term, although stone retained a role in many parts of life, copper and bronze took over many of the roles that many organic materials had previous had for the manufacture of tools.

The source of the Great Orme copper

The Great Orme is a grey limestone promontory surrounded on three sides by the sea. It emerges from the main coastline of north Wales at Llandudno, and is the same rock system that sits so dramatically along the western edge of the Clwydian Range above Llangollen. In a paper on the Great Orme research page, Cathy Hollis and Alanna Juerges explain some of the processes that took place to produce the mines on the Great Orme, of which the following summary is a much-simplified version. Go to the above link to see the detailed overview.

The Great Orme is a grey limestone promontory surrounded on three sides by the sea. It emerges from the main coastline of north Wales at Llandudno, and is the same rock system that sits so dramatically along the western edge of the Clwydian Range above Llangollen. In a paper on the Great Orme research page, Cathy Hollis and Alanna Juerges explain some of the processes that took place to produce the mines on the Great Orme, of which the following summary is a much-simplified version. Go to the above link to see the detailed overview.

The Great Orme limestone is a sedimentary rock formed of the accumulated remains of billions of calcium carbonate-secreting organic sea creatures that died and were laid down with rock salts in warm, shallow tropical seas during the Lower Carboniferous (c.335-330 million years ago). These include shellfish, foraminifera and corals, some of which can be seen as fossils in sections of the limestone on the Great Orme. There are multiple layers of the limestone on the Great Orme, often clearly visible, and each represents different phases of sediments as they were laid down. Around 330 million years ago this deposition of carbonates stopped, and the landmass of which the Great Orme was a part was eventually buried beneath a kilometer of other materials. In the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods, a collision between two shifting tectonic plates lead to folding and uplift of the landscape in north Wales, with faults torn across the Great Orme.

The faults allowed molten rocks, minerals and gases to escape. Amongst these escapees was dolostone, which in some places on the Great Orme altered the character of the limestone, becoming dolomite,or dolomitic limestone. The copper ores for which the miners were searching were found in veins that cross-cut the dolostone, meaning that they formed after it. This formation probably occurred during a new period of tectonic activity that was responsible for the uplift of The Alps and other European landmasses, including the Great Orme. The ores found their way into these new faults, and as this period of tectonic activity ended, and the atmosphere began to cool the molten materials, they slowly solidified where they lay. On the Great Orme, chalcopyrite was the copper ore that had inserted itself into seams of the limestone, and this was oxidized and became malachite. It was the malachite that was used for the manufacture of copper objects. Because much, but by no means all, of the limestone on the Great Orme was dolomitized, this created conditions that were favourable for mining. This new rock was much softer than the parent rock and some of it was highly friable and quite easily removed by bone tools.

The faults allowed molten rocks, minerals and gases to escape. Amongst these escapees was dolostone, which in some places on the Great Orme altered the character of the limestone, becoming dolomite,or dolomitic limestone. The copper ores for which the miners were searching were found in veins that cross-cut the dolostone, meaning that they formed after it. This formation probably occurred during a new period of tectonic activity that was responsible for the uplift of The Alps and other European landmasses, including the Great Orme. The ores found their way into these new faults, and as this period of tectonic activity ended, and the atmosphere began to cool the molten materials, they slowly solidified where they lay. On the Great Orme, chalcopyrite was the copper ore that had inserted itself into seams of the limestone, and this was oxidized and became malachite. It was the malachite that was used for the manufacture of copper objects. Because much, but by no means all, of the limestone on the Great Orme was dolomitized, this created conditions that were favourable for mining. This new rock was much softer than the parent rock and some of it was highly friable and quite easily removed by bone tools.

A further relevant process was the geomorphological activity that took place during the last Ice Age, the Devensian. The Irish Sea ice sheet that covered North Wales during the Devensian dragged down the surface of the Great Orme’s Head, scouring it of its upper surfaces as the ice sheet made its relentless way south. When the ice sheets finally retreated at around 11,000 years ago, Wales had been reshaped and re-profiled, and the the copper-bearing seams of the Great Orme had been exposed. The horizontal and vertical cracks in and fissures the limestone were further expanded by the subsequent action of rainwater erosion, groundwater and ice as the rock was subject to continual weathering.

For anyone interested in a full understanding of the geology, there are references at the end of this post in Sources.

Mining the ore

The copper mining process on Mount Gabriel at a similar date, by William O’Brien 1996, p.32 (see Sources at end).

As an industrial process, malachite had to be extracted first and then processed. Malachite is not the only ore that can be used to make copper metalwork and bronze, but is one of the simpler ones to process. As William O’Brien discusses, following his excavations at the Mount Gabriel copper mine in southwest Ireland, this requires prospecting, organizing mining teams, collecting raw materials and applying existing skills for the manufacture of tools to enable the extraction of ore and the specialized conversion of that ore to metal. O’Brien has put some elements of these workstreams into a diagram shown right, which gives a good sense of some of the processes involved (click image to enlarge). Although there are differences at the Great Orme, what this demonstrates very effectively is that there are three connected flows involved. The first, on the left of the diagram, is the collection of raw materials and the preparation and manufacture of tools and equipment. The second is the extraction cycle, and the third, in two stages, is the processing of ore.

Mining tools

The tools left behind in the Great Orme mines were mainly made of bone and stone, but there is evidence in the form of markings in the stone of bronze picks and chisels. Metals were almost certainly recycled rather than abandoned. Pottery was probably used for some tasks, although not much evidence of it is found at the mines, which suggests that other, more lightweight, less fragile and larger forms of carrier were preferred, made of basketry, leather or textile (such as sacking). All organic materials that are vulnerable to decay over time and are only very rarely found on archaeological sites and usually only in exceptional environmental conditions.

The tools left behind in the Great Orme mines were mainly made of bone and stone, but there is evidence in the form of markings in the stone of bronze picks and chisels. Metals were almost certainly recycled rather than abandoned. Pottery was probably used for some tasks, although not much evidence of it is found at the mines, which suggests that other, more lightweight, less fragile and larger forms of carrier were preferred, made of basketry, leather or textile (such as sacking). All organic materials that are vulnerable to decay over time and are only very rarely found on archaeological sites and usually only in exceptional environmental conditions.

By far the greatest number of tools, over 33,000 of whole and fragmentary pieces, were made of bone. Over half of these were cattle bone, and the rest were a mix of sheep, goat, deer and wild boar or pig, mainly ribs, limbs and shoulder blades. The long thin bones were used as picks, whilst the wide-based shoulder blades were used as shovels. Many of them were bright green when they were found, stained by the malachite.

Some of the stone hammers and mauls used in the mines, held today in the archaeological store on the site.

The majority of the stone tool collection is represented by over 2400 vast stone hammers with have been battered into their present shape by usage. At least some of them were thought to have fallen from nearby harder outcrops that were more durable than the softer local sedimentary rocks. Many of these were found on the local beaches, where they had been rolled and rounded. They varied in size from pieces that could be held by hand to enormous “mauls” that could be up to 20lbs in weight and would have been employed using some form of sling so that the stone could be swung into the rock face.

Possible reconstruction of the hafting of a Copa Hill maul from mid Wales showing how it may have been used in a sling. Source: Burrow 2011, p.90

Opencast shaft mining

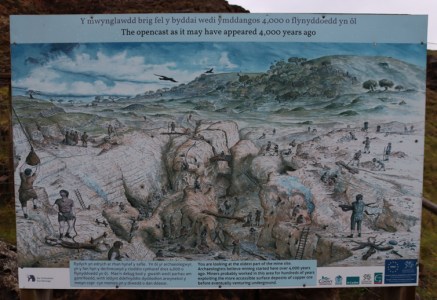

Helpful artist’s impression from the Great Orme mines of what the opencast mine would have looked like.

The earliest phase of Great Orme mining was opencast mining that took place in the Pyllau valley, as shown in the artist’s reconstruction left, on one of the information boards. The scoured landscape that the retreating ice-sheets had revealed permitted the prospectors to recognize the malachite-rich seams in the limestone, and to access it with relative ease by open cast mining. The techniques was to mine from the top down, removing the soft dolomitic limestone from in between the pieces of harder original limestone, creating the bizarre-looking landscape that remains today. This could be done using picks and shovels manufactured from bone, aided with hand-held hammerstones. A series of ladders, lifts and pulleys were probably required as the mines shafts became deeper, ready for copper processing on the surface. Eventually these stone shafts were exhausted and if the mines were to continue to provide copper, underground mining was the only solution.

Underground tunnel mining

Underground mining would have been very hard. Over the centuries eventually nine levels were excavated out of the limestone (of which two are included on the visit).

Some of the tunnels, like most of those shown in this post were tall and thin, allowing people to move down them upright in single-file. Some were significantly smaller, long and thin that could only be mined lying down by the smallest members of society – perhaps women and certainly, given how tiny the passages were, children. Others were opened out into large galleries like caverns, one of which is thought to be the largest surviving prehistoric man-made underground excavation in the world. One of the hollowed out galleries on the visit is filled with what are known as “deads,” the large fragments of waste rock left behind after ore had been extracted. It made more sense to backfill exhausted tunnels and galleries with waste then to remove it laboriously to the surface, where disposal would still have been a problem.

There were three methods of excavating malachite in the underground mines. The first continued to be bone picks for softer rock, the dolomitic limestones, but harder rocks eventually had to be mined as well. Harder rocks were excavated by a combination of fire-setting and stone tools. Stone tools, described above, included hand-held hammers and large mauls that would have been fixed in a sling in order to swing it at the mine face, both requiring the the input of energy and strength in a very difficult environment filled with stone dust and sharp fragments.

Simulation of a fire in one of the narrow shafts that head off horizontally from the bigger tunnels, thankfully without the smoke

Fire-setting added to the discomfort and raised the risk of serious injury. It consists of gathering a large pile of dead wood, which was placed against rock faces to be mined in order to make them more brittle and easier to work. Sometimes water could be added to the hot rock to help with the fragmentation process. The smoke created by the fire in such small spaces with no ventilation carried the risk of suffocating anyone in the vicinity, as well as the possibility of lung disease. Presumably the mines were vacated during this process, but the risk must still have been high for those who set the fires. In the long term, lung damage both from the smoke and the dust and fragments of stone must have been an ongoing problem.

Processing the ore

Cleaning the ore

In order to ensure that few impurities entered the smelting process, and that a good quality copper was obtained, the ore mined from the Great Orme had to be separated from the general waste material around it, called gangue. This stage in copper manufacturing is called beneficiation. When an ore was mined it was still attached to bits of rock and dust, and this had to be removed. This involved grinding, cleaning and sorting. Pestles and mortars were used to grind down the ore, and examples have been found at the Great Orme. Once it had been reduced, the mixture of rock and ore had to be sorted both by hand and eye, and usually by straining through running water. Once the cleaning process had been completed, it might be re-ground into a powder that could then be smelted. On the Great Orme a cleaning site was discovered and excavated at Ffynnon Rhufeinig, a natural spring that was run into a series of channels and ponds. the site was a kilometer away from the mines themselves, and it is suggested that the wider landscape was used during the Early Bronze Age phase of the site for processes connected with the mines, other than mining itself.

Copper smelting

Once the ore was sorted and cleaned, it underwent a process called smelting. Smelting is a term that refers to an ore being converted to a metal by the application of heat up to and beyond melting point. This took place above ground, and required specialized skills and equipment. So far only one smelting site has been identified at the Great Orme, dating to around 900BC, well after the copper mine’s main period of maximum exploitation, at a location some distance from the mine itself at Pentrwyn on the coast. Copper can be found in a number of different forms, some more difficult to process than others, but the malachite (copper carbonate) at the Great Orme required a relatively simple production methodology.

Display of prehistoric smelting equipment in a shelter on the pathway at the top of the opencast mine at the Great Orme.

After the ore had been cleaned, a furnace had to be built and prepared. The furnace was often formed by a pit with short walls. To this a clay tuyère was fitted, which was a tube that interfaced between the furnace and a pair of bellows. The bellows helped to raise the heat by blowing oxygen to feed the flames. This was an important factor because malachite needs to be between heated to between 1100 and 1200ºC before it will become molten. It runs the risk of mixing with the copper ore to become copper oxide, which cannot be used for metal production, so charcoal was also added into the furnace. The charcoal burns much hotter than wood, so contributed additional aid to the heating process but at the same time releases carbon dioxide as it burns, which helps to neutralize the impact of the oxygen on the ore, enabling it to become copper. The ore was heated in the furnace within a crucible, which is a vessel that will handle the high temperatures required for melting metals. The melted metal was then poured into a mould made of stone, pottery or bronze.

Bronze smelting

Bronze was a transformation of copper and tin into something entirely stronger and more resilient than either. It usually consisted of 90% copper and 10% tin, although later cocktails produced slightly different results. Tin lowers the melting point of copper, making it easier to convert the copper ore to liquid form. There were two methods used at the Great Orme. The first was by combining both copper and tin ore in a single smelting process. The second was adding tin or or to copper that had already been melted. As with copper, the Bronze was then moulded to form different tools and weapons.

The excellent video below shows a copper palstave under construction from the crushing of the ore using a pestle and mortar, via the smelting of the ore, to the moulding of the molten metal to the trimming of the final tool.

The manufacture of metal tools

Copper axe and stone mould from Durham. British Museum WG.2267. Source: British Museum

The earliest casting moulds in which the tools were formed were made of stone, and were open, with no top half. An example of an open stone mould from north Wales was found at Betws y Coed. The making of moulds became in itself a skilled task, creating the exact shape in stone that was required in the finished metal object, and they could create much more complex forms. Later,moulds could be made of clay or bronze. Once the copper or bronze had been poured into the mold and allowed to cool slowly, the object hardened and could be removed from the mould, to be finished by breaking off any excess metal and sharpening the blade. Initially only solid items like flat axes and more complex palstaves (such as the one shown below) were made.

Two parts of moulds for a palstave were found in three miles from the Great Orme in 2017 by a metal detectorist, shown below

Palstave moulds found near the Great Orme in 2017. Source: BBC News

Soon hollow or socketed objects were made as well, with the use of double-moulds and by inserting cores made of clay or other materials, which created a new way of hafting tools. and as these and the the socketed axe below shows, additional features like functional loops and decorative components could be added if required.

Bronze socketed axe head from Pydew, in the hills above Llandudno Junction, to the southeast of the Great Orme north Wales.

The copper miners

The early opencast miners would have been fit enough to undertake physical labour, and the first open cast mining required both knowledge and some basic skills, but once the knowledge was acquired, the rest would have been well within the capability of a farming or herding community. The veins of malachite sandwiched within soft limestone had to be recognized, and a strategy for extracting it and processing it had to be learned, but the ores could be excavated from soft dolomitized limestone using bone picks. The use of bone for tools rather than stone means that although it would have been a laborious task, it was not as back-breaking as tunnelling through solid rock.

This clearly changed. As the mining activities plunged underground and tunnels had to be excavated in the limestone to give access to the malachite, the miners must have been selected for more than merely strength and fitness. As stated above, it is entirely likely that women were employed in the task, being smaller than most men, and it is unquestionable that children were employed to excavate the slender warrens that only such small bodies could excavate and navigate. The community must have been in a position to replace its miners, because this was not merely back-breaking work, but dangerous too.

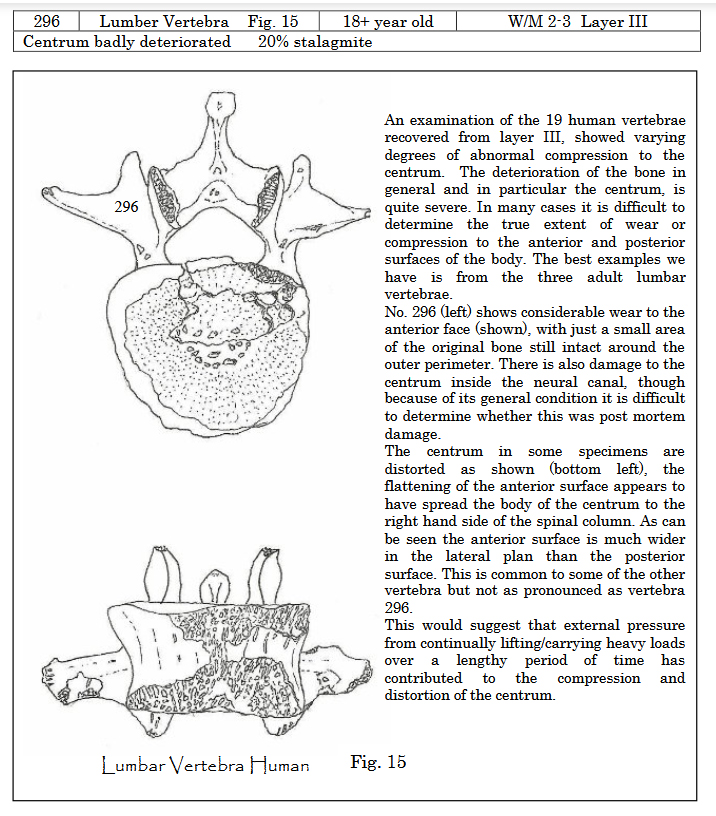

Damaged vertebra from the skeleton of an 18-year old found in a cave burial on the Little Orme. Source: John Blore 2012.

The risk to lungs and life from smoke, dust and rock particles has already been mentioned. Other dangers potentially included the collapse of walls and roofs, poor ventilation and the difficulties of lighting. No evidence has been found so far to show how the mines were illuminated, although there are a number of alternatives possible. As the mine went deeper, nearing the groundwater level, there may also have been danger of flooding. Wet stone from constant dripping in rainy and weather and falling rock must have been responsible for their fair share of bruises, cuts, head injuries and bone breaks, a potential problem where minimal medical knowledge was available and when infections could result in serious difficulty.

Long-term repetitive strain and stress injuries must have been common as well, leading to defects, as well as certain debilities and disabilities. A burial of four skeletons in the North Face Cave on the Little Orme, contemporary with the mines, shows that one of the individuals had sustained serious compression damage to his vertebrae, perhaps a result of extensive mining activity over a long period.

Although a number of settlement sites have been recognized on the Great Orme, not all of them were necessarily associated with the mines, although the characteristic round houses would have been the type of settlement familiar to the miners. It has been suggested that the mines may only have been worked on a seasonal basis, at least in the first decades, and that the miners belonged to farming communities whose main settlement sites were elsewhere, or that they were nomadic pastoralist who were either fully mobile or transhumant. Later on, when the mines were more intensively worked, more permanent lodgings may have been required. It is also possible that over the entire span of time during which the mines were used, settlements shifted positions.

The miners were not ill-fed, if the available evidence represents ongoing dietary possibilities, and there is nothing to suggest that there is any reason why they would not have been well sustained for the hard work undertaken, although conditions were certainly unpleasant. Sîan James has carried out post-graduate analysis of the bones found at the mines, which give some insight into what types of meat were consumed there. Sîan James’s research carried out at the Great Orme on the animal bones indicates that over cattle, which represent over 50% of the faunal remains, were butchered elsewhere and were brought to the site in manageable joints or portions. Sheep/goat (difficult to distinguish from one another in the archaeological record) and pig are also represented, making up the other half of the domestic species. No fish bones were found and only a handful of shellfish remains were discovered. Coastal resources were obviously not much used, if at all, at least at the mine itself. The picture that emerges is that the miners, at least whilst they were at the mines, relied on animal husbandry. They either maintained their own herds, were provided meat by their communities or acquired it by exchange with other groups.

Mining is an extreme form of landscape modification and management that impacted not only the immediate area of the mines themselves, but the surrounding landscape. Fire-setting and smelting would have required trees for burning on a much larger scale than previously known, and the miners would have required livestock in the vicinity for both food and raw materials. There can be little doubt that just as humans modified the Great Orme, the miners and their surroundings became entangled with the identity of the mining community and those connected with it. Although settlement and associated community activities may have been mobile, the mines were a fixed point on the Great Orme and an anchor that remained the same over multiple generations. The transmission of specialized craft knowledge from one generation to another may have differentiated the miners and smelters as a group apart, in either a good way, as valued contributors to the local wealth, or in a negative way, as an isolated minority alienated from normal community living. There is no way of knowing.

Mining is an extreme form of landscape modification and management that impacted not only the immediate area of the mines themselves, but the surrounding landscape. Fire-setting and smelting would have required trees for burning on a much larger scale than previously known, and the miners would have required livestock in the vicinity for both food and raw materials. There can be little doubt that just as humans modified the Great Orme, the miners and their surroundings became entangled with the identity of the mining community and those connected with it. Although settlement and associated community activities may have been mobile, the mines were a fixed point on the Great Orme and an anchor that remained the same over multiple generations. The transmission of specialized craft knowledge from one generation to another may have differentiated the miners and smelters as a group apart, in either a good way, as valued contributors to the local wealth, or in a negative way, as an isolated minority alienated from normal community living. There is no way of knowing.

Drilled amber bead from the North Face Cave burial on the Little Orme (from one of the visitor information signs).

Although it is beyond the scope of this post, understanding who the miners were is a matter of looking not only at the mines and the resources that supported them but at the burial sites and other monuments in the surrounding landscape that incorporated their ideas and beliefs. Their own burial monuments inhabited this space. On the Great Orme there are Bronze Age round cairns as well as a stone row and a possible stone circle. On the Little Orme the North Face Cave revealed the remains of four individuals buried at the time that the mines were worked, aged from 4 to 18 years old. A drilled amber bead was found with one of the burials. The Great Orme is dotted with the sites of those who came before. Neolithic sites and earlier Bronze Age sites are common here and throughout the uplands of north Wales, and the miners would have been aware of them. The landscape was inhabited not merely by the miners and by pastoralist herders but by their distant and recent ancestors, making this a spiritual as well as an economic landscape.

The Little Orme to the east of the Great Orme, seen from the Great Orme just above the copper mines. Llandudno follows the crescent of the bay between the two promontories.

From left to right. The Mold Cape superimposed on a digital sketch, which could be man or woman (Source: British Museum Partnership Programme); Photograph of the Wrexham County Borough Museum hologram of the reconstructed head of Brymbo Man (my photo); The recreated grave and capstone with original skeleton and grave goods of Brymbo Man in the Wrexham County Borough Museum (my photo).

There is a potential link between the Little Orme North Face Cave with the Bryn yr Ellyllon cairn. As well as the gold cape and other fine objects, numerous amber beads were found. One of the Little Orme burials was also accompanied by an amber bead, shown above. Amber beads are in themselves evidence of communications over long distances as amber was not available locally. It was sometimes washed up on beaches of northeast England, but otherwise had to be sourced from the Balkans and central Europe.My earlier series about two burial monuments in northeast Wales at Bryn yr Ffynnon (containing the remains of “Brymbo man” and a very fine Beaker) and Bryn yr Ellyllon (containing the Mold gold cape and other luxury objects) touches on some of these ideas.

The copper trade – selling and travelling

Trade and/or exchange

From a visitor centre sign showing the Voorhout hoard of bronze metalwork found in the Netherlands. 13 out of 17 of the objects were made with materials from the Great Orme

At the Great Orme the movement of goods falls into two parts. The first concerns the acquisition of tin for the manufacture of bronze from southwest England. The second concerns the distribution of metal or metalwork overseas.

The distribution of raw materials and tools in Britain was not unprecedented, and was a well known aspect of the Late Neolithic, where good quality flint from southern England (the uber-workable material for making small stone tools), and completed stone axe heads from Cumbria and north Wales, for example, had been conveyed from their geological sources to areas where they were unavailable. However, the linkages formed during the copper trade were new.

The copper trade probably started in response to local need, but by 1600BC it had upped its game to meet both a national and international need for bronze, which is made by the addition of tin. Tin is only available in a very small number of locations in southwest England, and the two, copper and tin, had to be brought together. Because the proportions of bronze were usually 90% copper to 10% tin, it made sense for the tin to be brought to the copper mining operation to be worked, and as a base for bronze mining the Great Orme became particularly successful. Given the relative locations of southwest England and the Great Orme, is is probable that the trade in tin was sea-based.

River routes showing how Group I shield-patterned palstaves made of Great Orme ores may have been distributed throughout Britain. Source: Williams and de Veslud 2019. Enlarge to see more detail

There is a question about why, at 1600BC the Great Orme was suddenly more productive than it had been before. One possibility is that other mines were exhausted at this time, some having been worked since the Chalcolithic and throughout most of the Early Bronze Age, but more data is required on this subject. Another is that It also needed a market for its products, and the development of the Acton Park industry (dating to around 1500-1400BC) created sufficient demand to sustain a well-placed mine with good connections to other areas.

As an economic enterprise, the Great Orme needed to ensure that its product arrived in the areas where there was demand. Using two types of data, a 2019 study investigated how Great Orme metals reached other parts of Britain and the continent. First, the researchers, Williams and Le Carlier de Veslud identified that a metalwork tradition known as Acton Park (named for its type site in Wrexham), made of Great Orme metals, was found in particular concentration in both the Fenlands of southeast England and in northeast Wales as far as its borders with England. The Fenlands help to demonstrate the reach of Great Orme metalwork to the east coast, whist the industry in northeast Wales presumably benefited from its relative proximity to the mine. A second object type, the Group I shield-pattern palstave, has also been used to help determine other locations where Great Orme metals were found, together with the routes that distributed them. The palstaves were found throughout most of Wales and southern Britain, as well as overseas, and the main concentrations seem to align with river systems, suggesting that the palstaves were distributed either by boat or by pack animals along river valleys.

Map at the visitor centre showing some of the European areas to which the Great Orme copper was sent

The presence of Great Orme copper and bronze overseas is particularly good evidence of sea-borne trade or exchange. Items such as the Voorhaut hoard from the Netherlands have been found as far away as Denmark and Sweden in the northeast, Poland in the east and in France, perhaps taken along the rivers Seine and the Loire in France.

In archaeology it is often unclear how both sides of an exchange may have operated. It is clear that metals were being manufactured and traded, but it is not quite as clear what the Great Orme miners were receiving in return. One possibility is that they were receiving livestock and cereals, but although this is certainly viable as one income stream, it seems to understate the value of the products being sold. Another option, which does not rule out the first, is that jet and amber, both of which are found in graves in north Wales were being sent west into Wales from the east coast, where these raw materials can be found, as prestige goods in return for Great Orme metals.

The only remaining bead, out of around 300, of a necklace of amber beads from the Mold Cape burial Bryn yr Ellyllon. British Museum 1852,0615.1. Source: British Museum

People are also often a little difficult to see clearly in archaeological data, but the metalwork industry of the Great Orme must have had more than miners and metallurgists to sustain it. It seems likely that when the processed metal and the finished artefacts were sent overseas, this must have involved middle-men who were not responsible for digging out the mines and smelting the ores, but were concerned with securing the tin from the southwest and sending the required products to wherever there was demand and payment. It has been suggested that the owner of the Mold Cape at Bryn yr Ellyllon near Mold, which included amber as well as gold, may have benefited from the wealth of the copper trade in order to be in a position to be buried with such luxurious objects, removing them from circulation in the living world.

As well as miners and middle-men there must have been additional people involved in the network who carried the metalwork from the Great Orme to where they were needed, perhaps returning with scrap metal for recasting. Although these people are usually, if not always impossible to identify with any confidence, they certainly existed. Some of them may have carried goods by pack animal, others by inland boats and coast-huggers, still others by vessels that were capable of crossing between England and the continent.

The end of copper mining in Britain

After the Early Bronze Age most of the copper mines went out of use in Britain and Ireland at around 1500-1600BC. The Great Orme was the exception, lasting until c.1300BC. As Richard Bradley says, it is not well understood why this and other changes in British mining occurred, “but they form part of a more general development in the distribution of metalwork which saw quite rapid oscillations between the use of insular copper and a greater dependence on Continental sources of supply.” A possibility suggested by Timberlake and Marshall in 2013 is that the decline in production, if not associated with the exhaustion of British mines, may have been the arrival of plenty of recycled metal from the continent, and particularly from The Alps at around 1400BC.

After the Early Bronze Age most of the copper mines went out of use in Britain and Ireland at around 1500-1600BC. The Great Orme was the exception, lasting until c.1300BC. As Richard Bradley says, it is not well understood why this and other changes in British mining occurred, “but they form part of a more general development in the distribution of metalwork which saw quite rapid oscillations between the use of insular copper and a greater dependence on Continental sources of supply.” A possibility suggested by Timberlake and Marshall in 2013 is that the decline in production, if not associated with the exhaustion of British mines, may have been the arrival of plenty of recycled metal from the continent, and particularly from The Alps at around 1400BC.

Final Comments

The above account is a description of the Bronze Age mines, and it was marvelous to read up about them. The copper mines at the Great Orme are one of the most vibrant places in Britain for getting a sense of people and their activities in our prehistoric past. Assuming that you are not claustrophobic and don’t mind being underground (about which more in “Visiting” below), this is a superb and revelatory experience. There is a strong sense of the lengths to which people in the Middle Bronze Age would go to supply the demand for copper. The sheer scale of the enterprise, as you literally rub shoulders with the past, is astounding. There is real feel of intimacy about the experience that is difficult to replicate at most other prehistoric sites in the UK. A visit is a powerful way of connecting with the miners, and a nearly unique insight into at least one aspect of Bronze Age living. Fabulous. Don’t miss it.

Visting

The Great Orme is one of a great many places of substantial interest in the area, and is easily fitted into a visit to the Llandudno and Conwy areas. Don’t miss Marine Drive, the road that runs around the Great Orme and allows you to get up close and personal with both the geology and the coastal scenery. If you like walking, the Great Orme has many footpaths, some of which take in other prehistoric sites as well as the nice little church of St Tudno, and if you like Medieval history the nearby Conwy Castle and the city walls along which you can walk, are simply brilliant. Conwy’s Elizabethan town-house Plas Mawr is one of Britain’s most remarkable Elizabethan survivors and is absolutely superb.

One of the Great Orme trams, also showing one of the cable car towers too. Photo taken just above the copper mine.

There is plenty of parking at the mines, but if you fancy taking the tram from Llandudno, which is a great option, the half way station is a five minute walk away. The mines are closed off-season so check the website for when they re-open. This year, 2024,they opened for the season on 16th March.

I visited at the end of March, not a peak time of year for visitors, and at 9.30am, which was opening time. I was literally there alone. By the time I returned to my car at 11.30am, having gone after my visit for a short walk to find a Neolithic burial site, it was beginning to get quite busy. There was what was a long stream of children being herded by adults headed for the visitor centre as I was driving away, and although I am sure that they had a splendid time, I’m very glad that I had made it out before they had made it in! If you don’t like crowds, I would suggest that avoiding school holidays and weekends would probably be a good idea.

Initially you go in via the visitor centre. The Visitor Centre is small but provides a very good introduction to the mines. There are information boards that do not go into great detail but still do an excellent job of introducing a complex subject, and there is a small cinema with a video running on a loop, which is a very helpful introduction to the mines. There are also relevant objects on display that provide a good insight into the job of the copper mines.

The visit to the mines is a circular route that includes both the inner mines and a walk above the open cast mines. In total, inside and out, it takes about 40 minutes. Initially the visit takes you underground, along the narrow horizontal shafts that were dug during the Bronze Age, with even smaller and narrower tunnels visible along the route, which would have been too small for adults to work.

The visit to the mines is a circular route that includes both the inner mines and a walk above the open cast mines. In total, inside and out, it takes about 40 minutes. Initially the visit takes you underground, along the narrow horizontal shafts that were dug during the Bronze Age, with even smaller and narrower tunnels visible along the route, which would have been too small for adults to work.

A note on claustrophobia and people with uncertain footing. If you are not good in confined spaces, read on. When they give you a non-optional adjustable hard hat to take in this is not a silly precaution to make you feel like an explorer – the head shield is very necessary. I bumped my hard-hatted head several times against the tunnel tops, and was very glad of the protection. The photo on the left is Mum in 2005, (not the most flattering view) and you can see that her red hard hat was necessary in one of the shorter stretches of tunnel. Underfoot you can be confident of a good, even surface, but it can be wet because limestone drips continually after rain. Sensible footwear is required. There are help buttons positioned around the walk, so there is the ability to call for help in an emergency, but this is not a place for someone who dislikes confined spaces or is worried about underfoot conditions. There is a flight of around 35 steps at both start and finish.

When you emerge from the tunnels, you follow the wide path that takes you above the opencast mines where there are more information boards and videos to see about both the Bronze Age mines and the 19th century mining works that first discovered the evidence of the prehistoric mining works, and this gives you an insight into a completely different type of mining.

When you emerge from the tunnels, you follow the wide path that takes you above the opencast mines where there are more information boards and videos to see about both the Bronze Age mines and the 19th century mining works that first discovered the evidence of the prehistoric mining works, and this gives you an insight into a completely different type of mining.

The route takes you back to the car park via the archaeological stores and the small gift shop. There was no information booklet for sale when I was there, and there were no general background books for sale either (unless my truffle-hound ability to sniff out books failed me). For anyone wanting to read up in advance, see my “Quick Wins” recommendations at the top of my list of Sources, just under the video below.

Sources

Quick wins

The list of books, papers and websites below shows the references that were used for this post, but that was a matter of cobbling together the story from many different sources. The official website for the Great Orme mines is a great resource for some very specific research papers but there is not a lot of background information.

The list of books, papers and websites below shows the references that were used for this post, but that was a matter of cobbling together the story from many different sources. The official website for the Great Orme mines is a great resource for some very specific research papers but there is not a lot of background information.

If you want to read up about Bronze Age mining and the Great Orme’s Head in advance and don’t have the time or inclination to your own cobbling, here are a couple of recommendations. Shire always does a good job of finding authors who can present a lot of information succinctly and informatively, and William O’Brien’s Bronze Age Copper Mining in Britain and Ireland is no exception, being both short and stuffed full of very digestible information about the Great Orme and several other mines, although just a little out of date having been published in 1996. There is a very good summary of the Great Orme mines in Steve Burrow’s well-illustrated and informative 2011 book Shadowlands, an introduction to Wales for the period 3000-1500BC (don’t be put off by the silly title – it is a National Museum of Wales publication, excellently researched, well written and well worth reading from beginning to end). Another good summary of the Great Orme can be found in Frances Lynch’s chapter in Prehistoric Wales published in 2000. The best detailed single reference for anyone who has academic leanings is the really excellent but seriously expensive Boom and Bust in Bronze Age Britain: The Great Orme Copper Mine and European Trade by R. Alan Williams (Archaeopress 2023), based on his PhD research at the Great Orme, but you can get the gist of some of his ideas in the 2019 Antiquity paper, Boom and bust in Bronze Age Britain by R. Alan Williams and Cécile Le Carlier de Veslud, which is currently available to read online free of charge: https://tinyurl.com/2d54yhax. Full details of all the above are shown below, in alphabetical order by author’s surname.

Books and papers

Where publications are available to read free of charge online I have provided the URL but do bear in mind the web address can change and that sometimes papers are taken down, so if you want to keep a copy of any paper, I recommend that you download and save it.

Blore, J. Updated 2012, Archaeological Excavation at North Face Cave, Little Ormes Head, Gwynedd 1962-1976. Unpublished excavation report

https://www.academia.edu/11888529/Archaeological_Excavation_North_Face_Cave_Little_Ormes_Head_Gwynedd

Blore, J. 2017. Radiocarbon Date for the Human Remains from North Face Cave, Little Orme’s Head, Gwynedd. Unpublished report

https://www.academia.edu/33487432/Radiocarbon_Date_for_the_Human_Remains_from_North_Face_Cave_Little_Ormes_Head_Gwynedd

Bradley, R. 2019 (2nd edition). The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press

Burrow, Steve. 2011. Shadowland. Wales 3000-1500BC. Oxbow Books / National Museum of Wales

Burrow, Steve. 2012. A Date with the Chalcolithic in Wales: a review of radiocarbon measurements for 2450–2100 cal BC. In (eds.) Allen, M J and Gardiner, J and Sheridan. Is there a British chalcolithic? People, place and polity in the late 3rd millennium. Oxbow Books, p.172-192

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314177072_A_Date_with_the_Chalcolithic_in_Wales_a_review_of_radiocarbon_measurements_for_2450-2100_cal_BC

Clarke, D.V., Cowie, T.G. and Foxon, A. 1985. Symbols of Power at the Age of Stonehenge. National Museum of Antiquities, Scotland.

Davies, Oliver. 1948. The Copper Mines on Great Orme’s Head, Caernarvonshire. Archaeologia Cambrensis The Journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. Vol. 100, p.61-66

https://journals.library.wales/view/4718179/4740893/106#?xywh=-2279%2C240%2C7491%2C3707

Farndon, John. 2007. The Illustrated Encylopedia of Rocks of the World. Southwater

Flemming, Nicholas. 2002. The scope of Strategic Environmental Assessment of North Sea areas SEA3 and SEA2 in regard to prehistoric archaeological remains The scope of Strategic Environmental Assessment of North Sea areas SEA3 and SEA2 in regard to prehistoric archaeological remains. Department of Trade and Industry

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265420489_The_scope_of_Strategic_Environmental_Assessment_of_North_Sea_areas_SEA3_and_SEA2_in_regard_to_prehistoric_archaeological_remains_The_scope_of_Strategic_Environmental_Assessment_of_North_Sea_areas_SEA3/citation/download

Gale, David. 1995. Stone tools employed in British metal mining. Unppublished PhD Thesis. University of Bradford 1995

https://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/10454/17157/PhD%20Thesis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Grace, Roger. 1997 The `chaîne opératoire approach to lithic analysis, Internet Archaeology 2

https://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue2/grace_index.html

Griffiths, Christopher J. 2023). Axes to axes: the chronology, distribution and composition of recent bronze age hoards from Britain and Northern Ireland. Proceedings of the Prehistoric

Society. Open Source.

https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/114422/1/axes-to-axes-the-chronology-distribution-and-composition-of-recent-bronze-age-hoards-from-britain-and-northern-ireland.pdf

Hollis, Cathy and Juerges, Alanna, Geology of the Great Orme, Llandudno. Great Orme Mines research page.

https://www.greatormemines.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Geology-of-the-Great-Orme-University-of-Manchester.pdf

James, Sîan E. 2011. The economic, social and environmental implications of faunal remains from the Bronze Age Copper Mines at Great Orme, North Wales. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Liverpool, March 2011. Great Orme research page

https://www.greatormemines.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Sian-James.pdf

Johnson, Neal. 2017. Early Bronze Age Barrows of the Anglo-Welsh Border. BAR British Series 632

Johnston, Robert. 2008. Later Prehistoric Landscapes and Inhabitation. In (ed.) Pollard, Joshua. Prehistoric Britain. Blackwell, p.268-287

Jowett, Nick. 2017. Evidence for the use of bronze mining tools in the Bronze Age copper mines on the Great Orme, Llandudno. May 2017, Great Orme Mines research page

https://www.greatormemines.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/article.pdf

Lynch, F. 2000. The Later Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age. In. Lynch, F., Aldhouse-Green, S., and Davies, J.L. (eds.) Prehistoric Wales. Sutton Publishing, p.79-138

O’Brien, William. 1996. Bronze Age Copper Mining in Britain and Ireland. Shire Archaeology. [Concentrates mainly on the site of Mount Gabriel, southwest Ireland]

Sheridan, A. 2008. Towards a fuller, more nuanced narrative of Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age Britain 2500-1500 BC. Bronze Age Review. vol.1, British Museum

https://britishmuseum.iro.bl.uk/concern/articles/28723733-e7b7-4726-aa04-1d89ad647048

Talbot, Jim and Cosgrove, John. 2011. The Roadside Geology of Wales. Geologists’ Association Guide No.69. The Geologists’ Association.

Timberlake, S. and Marshall, P. 2014. The beginnings of metal production in Britain: a new light on the exploitation of ores and the dates of Bronze Age mines. Historical Metallurgy 47(1), p.75-92

https://hmsjournal.org/index.php/home/article/download/112/109/109

Wager, Emma and Ottaway, Barbara 2019. Optimal versus minimal preservation: two

case studies of Bronze Age ore processing sites. Historical Metallurgy 52(1) for 2018 (published 2019) p.22–32

https://hmsjournal.org/index.php/home/article/download/31/29/29

Williams, Alan R. 2014. Linking Bronze Age copper smelting slags from Pentrwyn on the Great Orme to ore and metal. Historical Metallurgy 47(1) for 2013 (published 2014), p.93–110

https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3004718/1/Pentrwyn%20paper%20(R)%20Dec2014.pdf

Williams, Alan R. and Le Carlier de Veslud, C. 2019. Boom and bust in Bronze Age Britain: major copper production from the Great Orme mine and European trade, c. 1600–1400 BC. Antiquity, Volume 93 , Issue 371 , October 2019 , pp. 1178 – 1196

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/boom-and-bust-in-bronze-age-britain-major-copper-production-from-the-great-orme-mine-and-european-trade-c-16001400-bc/356E30145B1F6597D8AAA0DDBE69BD51/share/65e8e55c2c0c56fcf44096e0be28f1ff6f781f12

Williams, Alan R. 2023. Boom and Bust in Bronze Age Britain. The Great Orme Copper Mine and the European Trade. Archaeopress

Williams, C.J. 1995, A History of the Great Orme Mines from the Bronze Age to the Victorian Age. A Monograph of British Mining no.52. Northern Mine Research Society

Websites

Great Orme Copper Mines (official website)

Home page

https://www.greatormemines.info/

Research Page:

https://www.greatormemines.info/research/

BBC News

Great Orme: Rare Bronze Age axe mould declared treasure, June 1st 2022

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-61663012

Coflein

North Face Cave, Little Orme’s Head

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/307851/archives/

The Megalithic Portal – prehistoric sites on the Great Orme

Hwylfa’r Ceirw stone alignment

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=11133

Great Orme Head Cairn

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=45137

Lletty’r Filiast burial cairn

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=5300

Great Orme Round Barrow

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=7075

Great Orme Lost Chamber

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=7725

Coed Gaer Hut Circle

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=24791

Lower Kendrick’s Cave

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=10067

Upper Kendrick’s Cave

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=24756

Pen Y Dinas hillfort

https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=7727

Conwy County Borough Council

Discovering the Great Orme

https://www.conwy.gov.uk/en/Resident/Leisure-sport-and-health/Coast-and-Countryside/Assets/documents/Discover-the-Great-Orme.pdf

Great Orme’s Marine Drive Audio Trail and Nature Information Sheet

https://www.visitconwy.org.uk/things-to-do/marine-drive-audio-trail-p316681

Environment Agency Wales

Metal Mine: Strategy for Wales

https://naturalresources.wales/media/680181/metal-mines-strategy-for-wales-2.pdf

Based in Churton

Who was Brymbo Man, what was the Mold Cape and why do they matter?

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/2023/03/18/part-1-who-was-brymbo-man-what-was-the-mold-cape-and-why-do-they-matter/