Beeston crag is a superb landmark, a small outcrop of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge that was first occupied by people during the post-glacial period. Today, Beeston crag’s main claim to fame is the ruined 13th Century castle of Ranulf III, 6th Earl of Chester, built to intimidate his enemies, impress his allies, and provide himself with a magnificent legacy. Following the Ranulf III’s death in 1232 and the subsequent death of his heir in 1235, the castle was repaired and rebuilt on several occasions until the 17th century when it was deliberately destroyed. After this, the romance of the ruins attracted artists and tourist alike. Today it is managed by English Heritage and is an engaging visitor attraction. This has all been covered on two previous posts. Ranulf III’s Beeston Castle Part 1 looks at the remarkable magnate Ranulf III; Ranulf III’s Beeston Castle Part 2 describes the castle’s history and includes notes about visiting.

Beeston crag is a superb landmark, a small outcrop of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge that was first occupied by people during the post-glacial period. Today, Beeston crag’s main claim to fame is the ruined 13th Century castle of Ranulf III, 6th Earl of Chester, built to intimidate his enemies, impress his allies, and provide himself with a magnificent legacy. Following the Ranulf III’s death in 1232 and the subsequent death of his heir in 1235, the castle was repaired and rebuilt on several occasions until the 17th century when it was deliberately destroyed. After this, the romance of the ruins attracted artists and tourist alike. Today it is managed by English Heritage and is an engaging visitor attraction. This has all been covered on two previous posts. Ranulf III’s Beeston Castle Part 1 looks at the remarkable magnate Ranulf III; Ranulf III’s Beeston Castle Part 2 describes the castle’s history and includes notes about visiting.

Beeston Castle, showing the excavated Bronze Age and Iron Age posthole locations, marking hut circles in the outer ward (pink circles). The outer ward fortifications followed some of the lines of the Iron Age defences and the earlier Bronze Age banks. Both contemporary and earlier prehistoric sites were also found in other parts of the site. Source: Liddiard and Swallow 2007

Hidden beneath all of this rich Medieval and Civil War history is the archaeological story of the crag before history began. The impressive Medieval fortifications incorporate the remains of an invisible but remarkable prehistoric past, making the same use of a formidable location that dominates the Cheshire plain, with clear views to the north, east and west, providing safety from predatory animals in what was dense woodland below. Archaeologists between the 1960s and 1980s excavated these remains of the area’s prehistoric activity, some of it very exciting.

Although the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge as a whole is rich in prehistoric sites, in these two posts I simply want to get to grips with some of this particular crag’s prehistoric past. I have divided Beeston’s prehistory into a post about the earlier prehistory (in this part, part 1) and the later prehistory (in part 2). Other sites on the ridge will be mentioned in passing, and future posts will discuss what all of the research on the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge contributes to our knowledge of prehistory in Cheshire.

For anyone wanting to find out more about each of the periods of British prehistory mentioned, some excellent books are listed in the Sources at the end of each of the two posts.

This post has been divided into the following sections:

- Survey and excavation history

- A note on the Three Age system

- The role of the geology, geography and environment

- The archaeological sequence at Beeston

- Raw material acquisition at early prehistoric Beeston

- Final comments

- Next

- Sources

Survey and excavation history

Aerial view over Beeston crag showing its prominent position over the landscape. Source: Sandstone Ridge Trust

Some of the hillforts on the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge were excavated in the mid-1930s by William Varley, an archaeologist with the University of Liverpool. His excavations were focused on hillforts, and although there were some inconsistencies is his approach, and his interpretations are sometimes questioned, he established that there was information under the ground along the ridge, and that it was worth investigating further. Varley bypassed Beeston, but thirty years later new excavations filled this gap, focusing on both prehistoric and Mediaeval remains, a suitable endorsement of Varley’s initial exploratory work.

In the excavations of the 1960s-80s there were two main concentrations of excavation, one in the centre of the outer ward, and another by the outer gateway. Another fairly large area was opened to the south of the outer gateway, and some small cuttings were opened in other areas. Source: Ellis 1993 (with red circles added)

Two closely connected stretches of investigation are responsible for our understanding of the prehistory of the Beeston. These are Laurence Keen’s work between 1968 and 1973 and Peter Hough’s work between 1975 and 1985. These excavations found evidence of early as well as later prehistory, and made use of radiocarbon dating to establish a sound chronological sequence. The account on this blog post makes extensive use of those excavations, reported in Beeston Castle, Cheshire. Excavations by Laurence Keen and Peter Hough, 1968-1985 edited by Peter Ellis and published by English Heritage in 1993. Unfortunately, many of the tables and images were on microfiche, and although the core text is now available for download, the microfiches have presumably not been digitized.

Plan of the Outer Ward excavation findings. Source: Ellis 1993

Although a lot of interpretive schemes in archaeology extrapolate from very small samples of big sites, particularly hillforts, in the case of the Keen and Hough excavations, there were two reasonably large areas where the work was concentrated, a smaller but still significant trench and several useful cuttings to sample other areas within the locale. It is by no means straightforward to collate all this information into a coherent narrative, even if that is actually desirable with this sort of sampling, but some very useful findings were reported.

Some of the results of one of the sub-surface surveys in 2010. Source: an unpublished report, via Garner 2016.

No recent excavation has taken place at Beeston, but a series of geophysical and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) surveys were carried out by the Habitats and Hillforts Project in 2009 and 2010, at the outer ward and outer gateway. Although these produced no definitive results, they did identify some anomalies that could indicate where future excavation projects might concentrate their attentions. Much of the Habitats and Hillforts work has been published. Dan Garner’s 2012 short introductory booklet Hillforts of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, which looks at multiple periods of occupation, is very useful for becoming acquainted with the Cheshire Ridge archaeology. Garner’s 2016 academic volume Hillforts of the Cheshire Ridge is of considerable value for understanding both previous and current survey and excavation works at the other Cheshire Sandston Ridge sites in greater detail, particularly Eddisbury Hillfort.

A note on the Three-Age system

Thomsen explaining the Three-age System in Copenhagen, 1846. Drawing by Magnus Petersen, Thomsen’s illustrator. Source: Wikipedia

The 19th Century vision of a Three Age System, (Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age), devised by Danish antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen and published in 1836, was a spirited attempt to create a chronological framework for Danish prehistory that was widely adopted. It became associated with the idea that technological innovations were inextricably linked to human progress and, by extension, the superiority of industrial nations.

Although ideas have now changed, the Three Age system is still the main organizing framework within which prehistory is discussed. Having noted that the early Neolithic (New Stone Age) is an extension of the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), that the later Neolithic segues into the Early Bronze Age, as does the later Bronze Age into the early Iron Age, it is possible to move on. These issues are all dealt with comprehensively in the academic literature. The Three Age model still provides a framework within which most prehistoric archaeology is bashed out and bullied into shape, and as long as its limitations are kept to the fore, it need not be a wholly unyielding strait-jacket.

The role of geology, geography and environment

The location of Beeston within the Cheshire Sandston Ridge. Source: Garner 2012 (with red ring added)

Beeston is part of the fabulous Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, and those who selected it as an ideal place to settle, either temporarily or in the long-term, were presumably attracted by its height 150m above sea level, its location in a vast area of mixed deciduous woodland and, eventually, its defensive potential.

From a distance this prominent piece of geology looks like a complete anomaly, rising like a fossilized dinosaur’s spine out of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, knobbly and incomplete, but obviously the product of the same geological engine, the rocky components of the same machine. Beeston sits towards the southern end of the ridge. The Cheshire plain spreads from its base in all directions, the hills of the Welsh foothills to the west and the Peak district to the northeast, visible only in the far distance. The Cheshire Sandstone Ridge is made up of desert sands and pebbles up to 225 million years old. Questions about how the ridge formed and why it looks as it does are going to have to be the subject of a future post, written by someone else, but its upstanding presence in the otherwise flat landscape tell us, on its own, something about the prehistoric communities that, on and off over a period of nearly 8000 years, decided that it was a good place in which to camp or settle.

Archaeologically speaking, the sandstone composition is interesting because sandstone does not contain any of the stone types used used for the manufacture of stone tools. This means that the flint and chert used for such tools was brought here from somewhere else. This suggests not only that people were here for something other than the raw materials for tool manufacture but that they had to bring either the stone for tool manufacture with them, or the tools themselves.

Archaeologically speaking, the sandstone composition is interesting because sandstone does not contain any of the stone types used used for the manufacture of stone tools. This means that the flint and chert used for such tools was brought here from somewhere else. This suggests not only that people were here for something other than the raw materials for tool manufacture but that they had to bring either the stone for tool manufacture with them, or the tools themselves.

View from Beeston crag today west towards the Welsh foothills. In the Mesolithic and early Neolithic this would have been dense woodland. Clearance on the plain started in the later Neolithic but probably did not make significant changes to the patterns of vegetation until the mid Bronze Age to early Iron Age.

What the Cheshire Ridge has in abundance, other than sandstone, is height. This provides truly impressive visibility across the landscape, as well as respite from the dense woodland below. Whether or not the views across the plain would have been much use in earlier prehistoric phases is debateable, as the dense woodland would have disguised the approach of any but the largest groups of people. Even after extensive woodland clearance had carved out agricultural fields, this might have remained true. On the other hand, lines of sight to other communities on other parts of the ridge might have been important, and clear views of weather fronts could also have been value. Respite from dense woodland may have been relevant, especially when brown bear and wolves stalked the plains in hunt of meat of any description. The best way to avoid becoming something else’s dinner is always to remove oneself from its preferred habitat. It’s not a fool-proof strategy, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction.

Cattle grazing in a field below Beeston.

According to the Sandstone Ridge Trust, farming remains the major land use, with livestock farming dominating the area. This is interesting, as it tends to confirm the general impression that the damp clays of the Cheshire plain would have been difficult to cultivate in the past, particularly in early prehistory when the environment was much wetter and the area around the ridge included a network of freshwater springs. Woodland cover today exceeds 13%, which is high compared to nearby areas, but low compared to the probable coverage throughout most of prehistory.

A multi-period location

Archaeological chronology of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge. Source: Garner 2012

Wherever there is a medieval castle perched on a hilltop, it is worth looking for an Iron Age hillfort. They are often there to be found. It is also worth looking even further down the chronological funnel because some of the fortified prehistoric hilltops once synonymous with the Iron Age, are now known to have been built centuries before the Iron Age began. So wherever there is an Iron Age hillfort, it is worth bearing in mind that there may be a late Bronze Age predecessor, as was the case at Beeston. At Beeston the two phases of Iron Age hillfort were preceded by two phases of later Bronze Age settlement, one of which included an enclosing bank, and these were themselves preceded by even earlier prehistory – the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Early Bronze Age.

On the basis of previous work in the area, the excavators may have been hoping for prehistoric as well as Medieval finds, and they found evidence from the Mesolithic occupation from around 8000BC, dotted around all the way to the Romano-British period, which in Cheshire dates to c.70AD. These were small outposts of earlier prehistoric activity Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), Neolithic (New Stone Age) and Early Bronze Age, as well as more comprehensive discoveries of the later Bronze Age and Iron Age. The earlier prehistoric phases will all be discussed below and the later prehistoric in Part 2. Although there were discontinuities between the various occupations of Beeston, the crag was clearly of value to people of very different economic and social profiles over a very long period of time.

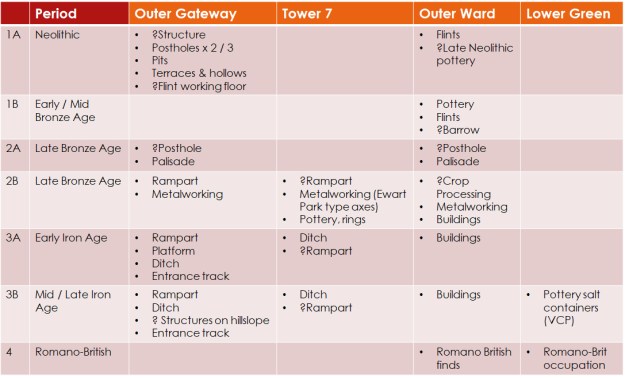

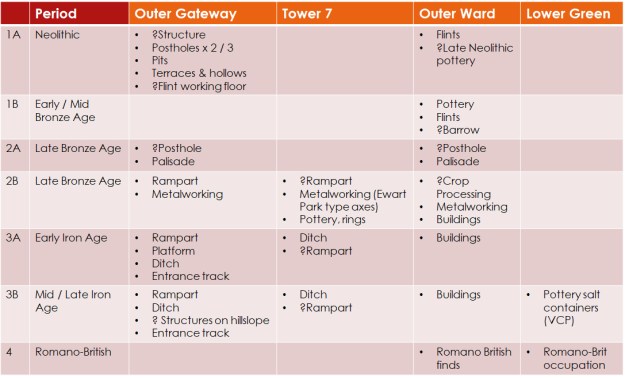

Archaeological periods at Beeston crag. Collated from Ellis 1993.

The Archaeological Sequence at Beeston

After the Ice Age, 9000-4000BC

Maximum extent of the Devensian ice-sheet. Much of the rest of southern England will have been encased in permafrost which only began to melt as the ice sheets retreated, starting at around 10,000BC. Source: Antarctic Glaciers

During the last Ice Age, the Devensian, glacial ice-sheets extended in an uneven line towards southern England, covering Wales and Ireland. The ice sheets carved out the u-shaped valleys that we all remember from school geography lessons, transporting huge amounts of debris from north to south, dropping thick deposits of soil and gravel, and creating meltwater channels. Vegetation was demolished either by the ice or by the temperatures, animals and people departed, and most of Britain was empty of life. Connected to the continent by a substantial land bridge, Britain only began to revive when the climate started to warm, and the ice began to melt. Vegetation, consisting of deciduous woodlands, shrubs and grasslands slowly returned to the lowlands, followed across the land-bridge by, amongst others, red deer, wild cattle (aurochs), reindeer, elk, brown bear, wolf and lynx. In their wake followed small communities of people who lived by hunting game, foraging for wild vegetables, roots, seeds, herbs and fruit, and fishing on the coast and in rivers. Today the period during which these groups of people returned and occupied post-glacial Britain is known as the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age. As the ice continued to melt and sea levels continued to rise, Britain was eventually physically cut off from the mainland, but that did not prevent other types of connection being established.

Mesolithic tools found from Beeston Castle, all less than 5cm long. Source: Ellis 1993

The Beeston Mesolithic finds are restricted to a small handful of stone tools that had been dislodged from their original context. These are very typical of the period, consisting of microliths (tiny stone tools), and other very small pieces. They do not say much on their own, but other Mesolithic sites in the area argue that the Beeston finds are a very small part of a much bigger Mesolithic story in the area. In particular, Harrol Edge near Frodsham produced over 1500 tools from the period and will be discussed further below. Other small sites are dotted along the Cheshire Ridge although most are as ephemeral as those at Beeston. These include an earlier and later Mesolithic phase at Carden Park near Broxton; Riley Bank Farm, Alvanley Cliff (all at the northern outcrop); and Seven Lows on the east edge of the central outcrop (a Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age site where around 100 pieces of worked flint were found). These are all surface scatters, not clearly defined and stratified sites, but they are valuable for indicating the presence of people at this time, suggesting the size of individual occupations and the period of time over which visits were made. Together, they argue for small, temporary stopping off points as the landscape was exploited for food, craft and tool manufacturing resources. They combine with other evidence to give an impression of a very busy pattern of landscape use in the Cheshire Ridge area, probably on a seasonal basis.

The Neolithic, 4000-2500BC

The later Mesolithic did not come to an abrupt end, any more than the Neolithic began as a rocket launch. The long period of transition between the two livelihood strategies were influenced by processes taking place on the continent, themselves innovated in the Near East. These presented opportunities and options, perhaps attractive to some and not to others, and take-up was no overnight phenomenon.

Neolithic stone tools from Beeston crag. Numbers 18 and 19 at the top of the image are earlier Neolithic leaf-shaped arrowheads. Source: Ellis 1993.

The changes that help to define the Neolithic (New Stone Age), when they began to gather momentum in around the third millennium BC, were characterized by a number of transformations that took place over the following 2500 years. The spread of the main features generally characterizing the Neolithic did not spread at the same rate throughout Britain, and not all characteristics were adopted at the same time, even in neighbouring areas. The main components defining the Neolithic are new forms of technology, a change of food acquisition practices, accompanied by new types of social statements. Continuities and discontinuities between the Mesolithic and Neolithic are eternally under debate, because they are central to the question of how the domesticated crops and livestock, stone tool technology and more nebulous spiritual ideas were introduced from the continent, adopted in Britain and then spread. Whatever the mechanism of their arrival in Britain, they became cornerstones of everyday life, and eventually found throughout Britain and Ireland, taking different forms in different areas, but based on a similar package livelihood opportunities, both economic and conceptual.

Early Neolithic of the Grimston/carinated tradition in northern Britain. Source: Malone 2001.

In parts of Britain, the Neolithic represents the first foray into mixed agriculture, with domesticated cereal crops and livestock and the adoption of pottery, which helped to introduce new cooking techniques, and to increase the variety of foodstuffs that could be consumed. It also improved storage of both solids and liquids, protecting them from insect and vermin, and took on cultural as well as economic roles. It is possible that after an initial foray into cereal production, pastoralism became the dominant approach to Neolithic food production. This was probably particularly true in areas like Cheshire, where the clays, meres, mosses and heathlands would have been anything other than ideal for crop cultivation, and where dairy and other livestock farming dominate today.

As people began to manage their livelihoods in new ways, novel ceremonial and funerary monuments were built, and pottery and stone tools began to enter the realm of the dead as well as the living. Long distance relationships, already a feature of some Mesolithic communities, extended, as the trade in axes and exotic materials expanded.

Grimston Ware sherds from Beeston (Royle and Woodward in Ellis 1993). The lovely replica showing what a complete carinated Grimston bowl would look like, is by Potted History

Information about the Neolithic in Cheshire, and particularly the Cheshire Ridge, is at best fragmentary, and it is not yet possible to pull together a coherent narrative of what is happening. As with the Mesolithic, settlement data, rarely in the form of structural remains and usually in the form of secondary scatters of objects on the surface, are generally small and dispersed but together contribute to distribution maps to indicate, at the very least, where Neolithic people were present, and what form their presence took.

At Beeston, objects of both the earlier and mid Neolithic were placed by Ellis in his 1A phase. Objects diagnostic of the earlier Neolithic include leaf-shaped arrowheads (above), and carinated bowls (right) that used to be referred to as Grimston or Grimston-Lyles Hill ware, generally in circulation from c.3750BC. The carination here is the rim that circles the centre of the vessel, and in general refers to a vessel’s wall making a sharp change of direction. At Beeston both leaf-shaped arrowheads and sherds of carinated bowl are present, although the pottery is very fragmentary. Because clay was fired at relatively low temperatures, and because temper in the fabric was often organic or composed of stone pieces, the pots were relatively fragile and once abandoned, were vulnerable to frost and heat damage and to erosive forces. It is therefore comparatively rare to find Neolithic pottery found in tact. Although Grimston carinated wares continued to be used for hundreds of years in some areas, in most they were replaced by more regionally distinct styles.

The leaf-shaped arrowheads that were spread widely through Britain had no antecedents in the Mesolithic, they suggest that hunting still formed part of subsistence activities. The hand-made (as opposed to wheel-thrown) carinated pottery. Carinated bowls were found in a wide range of contexts in Britain, from pits and middens to early burial contexts, but there is no evidence of burial sites of this date either at Beeston or nearby.

The early to mid Neolithic phase at Beeston’s outer entrance under excavation. You can see the stone walls of the Medieval castle in the background. This area is at the entrance to the outer ward, so when you pause to walk through the gap in the walls, remember that a Neolithic site was found underfoot. Source: Ellis 1993.

Another area of Neolithic at occupation at Beeston was found during the excavation at the outer gateway to the Medieval castle. The Neolithic phase in this area was marked by terraces, hollows, pits and postholes. There had clearly been an attempt to provide a level surface, implying some investment in the site, suggesting either the intention to stay put for some time, make repeat visits annually, or return at seasonally. As well as this evidence of settlement, there were stone tools including small axe heads and the sherds of four types of Neolithic pottery, spanning the early to mid Neolithic.

Additional Neolithic material was found on the plateau edge. A deep pit cut into the bedrock and a smaller pit or posthole were accompanied by a single early-mid Neolithic sherd, at the base of the deep it. It is difficult to assess, but the excavators suggest that it may mark a former entrance. Finally, a single Late Neolithic sherd was found in Post-Medieval layers in the outer ward, where the Bronze Age and Iron Age hut circles were found.

Were these Neolithic occupants permanent cultivators who carved out fields in the woodland below, peripatetic livestock herders, or occasional visitors making use of the outcrop as a supplement to activities on the plain or elsewhere? There are no plant or animal remains surviving to give us a hint. The evidence from pollen analysis indicates that post-glacial Beeston developed in the context of mixed oak woodland and Ellis says that pollen data from north of Beeston suggests an initial clearance phase, but that this did not happen until the third millennium (i.e. between 3000BC and 2000BC, in the later Neolithic). At Eddisbury hillfort, excavations in 2010 produced wood charcoal and other vegetation remains that suggest heath or moorland conditions that are generally associated with human manipulation of the landscape, in particular livestock grazing. It is possible that the ridge outcrops were being used for seasonal upland herding activities. Patches of grassland would have been ideal for grazing sheep, and coarse shrub for browsing goat, whilst cool woodland on the plain, particularly oak with its acorns, would have suited pigs perfectly.

Neolithic worked tools from Beeston Castle. Source: Liddiard and Swallow 2007

There are other explanations possible as well. The small size of the assemblages may suggest scouting parties or small detachments engaged in resource aquisition tasks, heading east to west or north to south, and heading up hill for safety en route somewhere else.

All of the above is pure speculation, based on livelihoods practiced elsewhere, but it is the sort of speculation that ensures that when new data emerges, different models of occupation can be tested against the cumulative findings.

Although ceremonial and burial monuments are characteristic of some regions, nothing of this sort on the ridge or, to date, in the immediate landscape have been found in the early/mid Neolithic. Not until right at the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of the Early Bronze Age, when round barrows begin to appear on the sandstone ridge, and beaker remains were found at Beeston. This is at least 2000 years after the leaf-shaped arrowheads that we looked at above. I’ve covered beakers and round barrows in the Early Bronze Age section below, although they might just as well be termed Late or Final Neolithic.

Although only a small area of Neolithic land modification was identified, and there are only a handful of artefacts, it is worth remembering that only a small part of the entire crag was sampled. That’s not anyone’s fault, because it would take decades to dig up the entire thing. The excavation sample was actually impressive, and it does mean that there may well be other examples Neolithic land modification and objects to discover both on Beeston and other outcrops, as well as in the surrounding landscape. Although it’s a trite analogy, every new site, however small, is an important part of the Neolithic jigsaw, not only allowing insights locally, but contributing to how we understand differences from and linkages between geographical areas in Britain. Fortunately, excavation programmes are ongoing under Habitats and Hillforts Project and as all of this Cheshire Sandstone Ridge data is collated, it will hopefully provide an increasingly coherent understanding of Neolithic livelihoods on parts of the ridge and the surrounding area.

Early Bronze Age / Beaker period c.2500-1700BC

Earlier and Later Bronze Age sites along the Cheshire Ridge. Source: Garner 2012

In most parts of the country there is no clear delineation between the Late Neolithic and earliest version of the Bronze Age, sometimes referred to as the Copper Age or chalcolithic (roughly, the copper stone age) because copper appeared before bronze was introduced. A new type of pottery, the Beaker, is also characteristic of this cross-over period, together with a range of associated objects.

It has been clear to archaeologists for a long time that the Beaker tradition was communicated to Britain and Ireland from the continent, where its geographical presence was widespread, found in Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, and the Iberian peninsula. A multi-disciplinary DNA analysis research project in 2017 proposed that a significant percentage of the indigenous population of Britain was, by the Middle Bronze Age, replaced by those who brought the Beaker tradition with them at the end of the Neolithic. Here’s an excerpt from the report (Olalde et al 2017).

The arrival of the Beaker Complex precipitated a profound demographic transformation in Britain, exemplified by the absence of individuals in our dataset without large amounts of Steppe-related ancestry after 2400 BCE. It is possible that the uneven geographic distribution of our samples, coupled with different burial practises between local and incoming populations (cremation versus burial) during the early stages of interaction could result in a sampling bias against local individuals. However, the signal observed during the Beaker period persisted through the later Bronze Age, without any evidence of genetically Neolithic-like individuals among the 27 Bronze Age individuals we newly report, who traced more than 90% of their ancestry to individuals of the central European Beaker Complex. Thus, the genetic evidence points to a substantial amount of migration into Britain from the European mainland beginning around 2400 BCE.

As is so often the case with this sort of DNA research, as highlighted in the study itself, there are questions remaining about the extent to which it is possible to extrapolate from the data used, including sampling issues (statistical, geographical and relating to the quality of the material). However, although the question about how and why the continental Beaker objects and ideas became so popular remains open to some extent, it seems probable that as well as cultural dispersal of ideas and practices, some level of migration took place. However it happened, at the end of the Neolithic the continental Beaker and associated objects did become desirable, and were found extensively under round barrows, as well as occasionally in other contexts, in many parts of Britain. The cultivation of cereals also appears to have been resumed in some areas and intensified in others at this time, with new roundhouses being built in domestic contexts.

Distribution of some of the round barrows in Cheshire. Source: Morgan and Morgan 2004.

Beakers are not as common in northwest England as they were in the south, and only one complete Beaker, a long-necked type, has been found in Cheshire, in a round barrow burial Gawsworth, which is in the far east of the county, near Macclesfield. The Beeston Beaker-related finds fall within Ellis’s 1B phase. They were found at the Outer Gateway and in the Outer Ward. In all cases they were found in amongst later material, within later prehistoric and Medieval material and postholes. They consist of Beaker fragment, collared urn and/or pygmy cup fragments, a barbed and tanged arrowhead and four knife blades. In Ellis’s collation of the excavations by Keen and Hough, the pottery analysis by Royle and Woodward interpreted the Beeston Beaker and its associated finds, as evidence for a vanished barrow burial. There has been extensive use of the outer wards since prehistoric times with considerable quarrying and levelling on all areas of the plateau, so it is not impossible that a round barrow had been built and later destroyed. Beakers could, however, also be found as broken sherds in isolated pits, as well as in domestic contexts. Other new forms of pottery followed in the Early Bronze Age, including food vessels, cordoned urns, collared urns and pygmy/accessory cups, of which a number of examples have been found along the Cheshire Ridge.

Seven Lows assemblage with Beaker sherds. British Museum 1862,0707.64. Source: British Museum

Round barrows with Early Bronze Age finds in them have been found in the Cheshire Ridge area. Examples shown on the map above are Carden Park at Broxton, Castle Cob, Glead Hill Cob, Peckforton, High Billinge, Little Budworth and the Seven Lows barrow cemetery. Few have been excavated in modern times, but most were cremations. Only Clead Hill produced metal, in the form of a single bronze pin. It was accompanied by two barbed and tanged arrowheads, collared urns and a pygmy/accessory cup, all consistent with Early Bronze Age burial assemblages. The most common form of metal dating to the Early Bronze Age in the area was in the form of isolated finds of flat axe heads, but there are only four of those in the general vicinity. The recent excavation report for Seven Lows has just been reported (it arrived through my letterbox yesterday) by Dan Garner in the Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, so there will more on that site on a future post.

There is even less information for the Beaker-related presence at Beeston than the Neolithic, but what has been found is not inconsistent with other finds in the area, and it is to be hoped that further excavation will lead to a more complete understanding of the Beaker tradition in the Cheshire Ridge area.

Raw material acquisition at early prehistoric Beeston

Sourcing stone

Flint and chert were the materials used by the tool makers who left their tools at Beeston Crag. Because of the way in which the stone fractures predictably when hit by a hard or soft object, flint and chert are favoured for flaked stone tool manufacture. A remarkable amount of precision is achieved, meaning that multiple classes of foot types can be manufactured which, once identified by archaeologists, can be categorized and can contribute to an understanding of livelihood transformation and regional differentiation.

Mesolithic flint and chert tools from the Adams collection, collected at Harrol Edge, Frodsham. Source: Brooks, in Garner 2016

The sandstone ridge was not the source of the raw materials used in the earlier prehistoric period for stone tool manufacture. At Harrol Edge, near Woodhouse Hill at Frodsham, over 1500 pieces of Mesolithic worked stone pieces were gathered during unofficial fieldwalking in the 1950s by local resident J. Adams, since donated to the Grosvenor Museum in Chester.

For the flint, an analysis of the Harrol Edge tools by Ian Brooks identifies two sources, in chalk deposits of the Lincolnshire/Yorkshire wolds or Northern Ireland. This does not necessarily mean that people had to go to either place or engage in trade to source the stone, because the ice-sheets transported considerable amounts of stone material to parts of the country to which it was not native, and Irish Sea till (unsorted material deposited by the movement of glacial ice) and associated gravels have been found in the valley of the River Weaver, which runs to the east of the sandstone ridge.

The nearest chert deposits were found in limestones in the Peak District and on the edge of the Vale of Clwyd (sometimes referred to as Gronant chert but properly part of the Pentre Chert Formation). This means that however these stones were being sourced, they had to be transported to the site either as a raw material for working into tools, or as finished objects.

More Mesolithic stone tools from Harrol Edge, Frodsham. Source: Garner 2012

Hunter-forager-fishers of the Mesolithic were seasonally mobile, moving base camps to make the most of food and craft resources. It is more than probable that in their seasonal rounds they were able to source chert and flint. There is insufficient evidence from Beeston itself to suggest how stone was being processed, but of the 1500 pieces from the Harrol Edge collection, only 266 were actual artefacts, consisting of 232 blades and 34 scrapers, and the rest were by-products of the manufacturing process, representing multiple took making events. This suggests that most of the artefacts were being made here, wherever the finished tools were eventually discarded, meaning that the raw material was brought to the site to be worked, rather than being worked where it was found. Most of the objects were made on flint, mainly a distinctive banded variety, and only 8.6% were on a dark-coloured chert. The chert tools may have been earlier in date than the flint examples. Brooks says that the banded flint was not wholly ideal for knapping into shape, and probably would not have been the first choice if an alternative had been readily available. Brooks felt that it probably came from the Peak District, but did not rule out north Wales as a possibility.

Knapped stone arrowheads from the Neolithic. Source: Malone 2001

In terms of the Neolithic stone use at Beeston, even early farmers were often far from sedentary, making their way through the landscape as they herded, seeking out craft materials on a seasonal basis and looking for new opportunities to exploit tracts of lowland and upland. Early farmers were often far from sedentary, making their way through familiar landmarks of the landscape as they herded on a seasonal basis, seeking out craft materials on a and looking for new opportunities to exploit both lowland and upland environments. It is possible that the local glacial tills provided the necessary flint for small tools, but even if travel had been required or the acquisition of raw materials, it would not have been necessary for the entire community to relocate. For example, a dedicated resource acquisition group could have been dispatched from the group for this specialized task. At the moment all we know for sure is that Neolithic groups were in the area, and that they imported flint and chert, either as raw material or as completed tools, from outside the area.

At Beeston the Early Bronze Age stone tool assemblage consists of a flint barbed and tanged arrowhead and four knives, all flint, and all nicely worked. There is not much to be added to the above comments, but the knives were made of bigger pieces of flint than previous items, and it seems less likely that the raw material for such items would have been carried for any distances. I have no idea whether or not flint pieces this size could have been found in the nearby valley gravels.

Sourcing materials for pottery

Collared urn sherds from Beeston (Royle and Woodward in Ellis 1993) and a photograph of collared urn from Seven Lows (source: Megalithic Portal)

The excavation report refers to three types of phase 1a and 1b pottery at Beeston. All of them are made from local glacial drift clays characteristic of the Cheshire/Shropshire basin. For example, the mineral inclusions (called temper) that were added to the collared urn clay during the pottery making process included quartz, sand, granite, rhyolite and basalt, all of which were common to other collared urns in Cheshire, and all of which could be sourced from local river valleys and glacial gravels in the area. Because both the clay and the temper were available locally, vessels could be manufactured within the immediate area, although there is no actual evidence to date for pottery manufacture at any of the Cheshire sites. Although these vessels were hand formed rather than wheel-thrown, they still needed to be fired, and so far no evidence has emerged in the area for Neolithic kilns (usually simple pit kilns).

Final Comments

Although Beeston crag has produced the greatest evidence of early prehistoric occupation along the line of the Cheshire Ridge, this is probably due mainly to an accident of sampling. Other hillforts were simply not excavated as extensively as Beeston, meaning that there could be plenty of early prehistory to be found at other Cheshire Ridge outcrops. There have been some indications that there is more to be found. At Eddisbury hillfort, for example, a possible late Neolithic cremation cemetery has been identified; at Seven Lows barrow cemetery at the eastern foot of the central outcrop, a recent excavation has just been published in the Chester Archaeological Journal (issue 8); at Woodhouse a small assemblage of Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age stone tools were found, and at Helsby some early Neolithic activity has been identified. Stray finds have been found elsewhere along the line of outcrops.

The so-called Beeston Hoard. Source: Varley and Jackson 1940

So far all the archaeological focus has been on the outcrops of the ridge, but that too is something of a sampling problem. Because of the considerable agricultural value of the land across the Cheshire plain, it is unlikely that many upstanding sites are left to be found, and any settlement sites are likely to have been ploughed in. Aerial photography has proved to be of marginal value due to the water retentive properties of the glacial soil, which prevents it drying out sufficiently to show variations in the soil during dry weather. However, there are hints that prehistoric archaeology may yet be found. On the plain not far from Beeston, the so-called “Beeston hoard” was found on the edge of a former freshwater spring, consisting of a Neolithic polished stone axe and an Early Bronze Age perforated stone axe-hammer. The remains of a round barrow surrounded by a ring of stones and a circular ditch were found at Morreys garden centre at Kelsall, containing the cremated bones of a child in an inverted collared urn. Unfortunately, discoveries like that have been few and far between.

Barbed and tanged arrowhead from Beeston – Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age. Source: Ellis 1993

The discovery of earlier prehistoric sites along the course of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, many only excavated only briefly and some not excavated at all, establishes that there is the opportunity for further investigation, and hopefully further illumination. There are a lot of questions remaining open about the earlier prehistory of both the ridge and the surrounding landscape. Clearly, there is a lot of future potential for both non-invasive survey and excavation, should the funding be available.

Next

Following a visit to Beeston to enjoy the castle on a fine, sunny day last year, I became aware that Beeston had something of a prehistoric past, but I was surprised by how rich that past turns out to be, particularly when seen within the context of other sites on and around the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge. At Beeston it begins with the Mesolithic occupation from around 9000BC, and then takes in the early Neolithic and the later Neolithic/earlier Bronze Age. In Part 2, the very striking Bronze Age and Iron Age round-house and related discoveries on the Beeston crag take us all the way to the Romano-British period.

Sources for Parts 1 and 2:

Items in bold were used extensively in this post, with my thanks.

Books and papers:

Berridge, P. 1994. The Lithics. In (ed.) Quinnell, H., Blockley, M.R. and Berridge, P. Excavations at Rhuddland, Clwyd, 1969-1973. Mesolithic to Medieval. BAR 95, CBA.

Bradley, R. 2019 (2nd edition). The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press

Callaway, E. 2018. Divided by DNA: The uneasy relationship between archaeology and ancient genomics. Nature, March 28th 2018

Cunliffe, B. 1995. Iron Age Britain. English Heritage/Batsford

Cunliffe, B. 2005 (4th edition). Iron Age Communities in Britain. Routledge

Ellis, P. (ed.) 1993. Beeston Castle, Cheshire. Excavations by Laurence Keen and Peter Hough, 1968-1985. English Heritage

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1416-1/dissemination/pdf/9781848021358.pdf

Fairhurst, J. M. 1988. A Landscape Interpretation of Delamere Forest. May 1988

http://delamereandoakmere.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/fairhurst-delamere-landscape.pdf

Garner, D. 2012. Hillforts of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge. Cheshire West and Chester

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/doc/D234636.pdf

Garner, D. and contributors 2016. Hillforts of the Cheshire Ridge. Archaeopress (appendices only available online)

http://www.archaeopress.com/ArchaeopressShop/Public/displayProductDetail.asp?id={2B433802-E7A0-4302-B2DD-95B7F3B2A493}

Garner, D. and contributors 2021. The Seven Lowes prehistoric barrow cemetery, Fishpool Lane, Delamere, Cheshire: a reassessment. Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, volume 91, 2021

Gibson, A. 2020. Beakers in Britain. The Beaker package reviewed. Préhistoires méditerranéennes no.8 (Ethnicity? Prestige? What else? Challenging views on the spread of Bell Beakers in Europe during the late 3rd millennium BC)

https://journals.openedition.org/pm/2077

Liddiard, R. and Swallow, R.E. 2007. Beeston Castle. English Heritage

LUC 2018. Cheshire East Landscape Character Assessment 2018. Land Use Consultants

https://www.cheshireeast.gov.uk/planning/spatial-planning/cheshire_east_local_plan/site-allocations-and-policies/sadpd-examination/documents/examination-library/ED10-Cheshire-East-LCA.pdf

Mackintosh, D. 1879. Results of a systematic survey in 1878 of the direction and limits of dispersal, mode of occurrence and relation to drift deposits of erratic blocks our boulders of the west of England and east Wales, including a revision of many years’ previous observations. The Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 53, p.425-55

Malone, C. 2001. Neolithic Britain and Ireland. Tempus Publishing

Matthews, D. 2014. Hillfort intervisibility in the northern and mid Marches. In Saunders, T. (ed.) Hillforts in the Northwest and Beyond. Archaeology NW new series, Vol.3, Iss.13 for 1998. CBA NW.

Mayer, A. 1990. Fieldwalking in Cheshire. Lithics 11, p.48-50

http://journal.lithics.org/wp-content/uploads/lithics_11_1990_May_48_50.pdf

Morgan, V.B. and Morgan, P.E. 2004. Prehistoric Cheshire. Landmark Publishing

Needham, S. 1993. The Beeston Castle Bronze Age Metalwork and its Significance. In Ellis, P. (ed.) Beeston Castle, Cheshire. Excavations by Laurence Keen and Peter Hough, 1968-1985. English Heritage

Olalde, O. 2017. The Beaker Phenomenon and the Genomic Transformation of Northwest Europe. bioRxiv May 2017

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/135962v1.full.pdf

Ormerod, G. 1882. The history of of the county palatine and city of Chester. Routledge

Ray, K. and Thomas, J. 2018. Neolithic Britain. Oxford University Press

Royle, C. and Woodward, A. 1993. The Prehistoric Pottery. In Ellis, P. (ed.) Beeston Castle, Cheshire. Excavations by Laurence Keen and Peter Hough, 1968-1985. English Heritage

Stuart, R. 1993. The flint. In Ellis, P. (ed.) Beeston Castle, Cheshire. Excavations by Laurence Keen and Peter Hough, 1968-1985. English Heritage

Varley, W.J. and Jackson, J.W. 1940. Prehistoric Cheshire. Cheshire Community Council

Weaver, J. 1995 (second edition). Beeston Castle. English Heritage

Websites

Habitats and Hillforts Project

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/projects/habitats-hillforts.html

Sandstone Ridge Trust

Leaflets about the archaeology of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, available to download as PDFs

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/about-sandstone-ridge-trust/publications.html

Archaeology

The Archaeology of Helsby Hill (PDF, 475KB)

The Archaeology of Woodhouse Hill (PDF, 487KB)

The Archaeology of Kelsborrow Castle (PDF, 495KB)

The Archaeology of Eddisbury Hill (PDF, 451KB)

The Archaeology of Beeston Crag (PDF, 498KB)

The Archaeology of Maiden Castle (PDF, 432KB)

Habitats

Broadleaf woodland (PDF, 352KB)

Meres and mosses (PDF, 391KB)

Lowland heath (PDF, 337KB)

Species-rich grassland (PDF, 331KB)

Insights Paper. The Sandstone Ridge Trust, 2018 (PDF, 7.6MB)

Sandstone Ridge Atlas. The Sandstone Ridge Trust (PDF, 22.3MB)

Delivery Model Options Appraisal. The Sandstone Ridge Trust (PDF, 2.4MB)

Ridge: Rocks and Springs

Ridge: Rocks and Springs Evaluation Report. The Sandstone Ridge Trust, 2017 (PDF, 37.4MB)

The Ridge: Rocks and Springs — a sandstone legacy. The Sandstone Ridge Trust, 2017 (PDF, 108.8MB)

Interim Report: Urchin’s Kitchen. The Sandstone Ridge Trust, 2017 (PDF, 67.5MB)

Ridge: Rocks and Springs Project Handbook 2015. A volunteer’s guide. The Sandstone Ridge Trust, 2015 (PDF, 7.7MB)

Habitats and Hillforts

Habitats and Hillforts Evaluation Report. Cheshire West and Chester Council, October 2012 (PDF, 12.5MB)

Hillforts of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge. Dan Garner, Cheshire West and Chester Council, October 2012 (PDF, 10.8MB)

Captured Memories. Cheshire West and Chester Council, 2011 (PDF, 100.2MB)

Fertile Ground. Art & Photography inspired by Cheshire’s Sandstone Ridge. Cheshire West and Chester Council, 2012 (PDF, 66.5MB)

Geology

Introduction

Our Geological Heritage

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/special-place/rural-land-uses.html

Bodnant Gardens are currently stunning. Bodnant is always stunning, and it gets better every year. This time of year is one of its particularly shining moments, with the laburnum walk and the last of the azaleas, the rhododendrons in full bloom, the wisteria flowing like water, fabulous guelder rose (actually a viburnum), a few glossy camellias still in flower, some charming early roses, and enormous pieris shrubs the size of trees blooming with flowers that look like lily of the valley. These are complemented at ground level with some brightly coloured arrays of perennial flowers, glossy and eye-catching, even in the deep shade, where careful choices have produced fabulous results. The formal ponds were dignified and peaceful, whilst the bubbling brook at the bottom of the valley was utterly stunning, with birdsong and water over stones combining to create an audio-visual sense of peace and harmony that was really rather magical. Even the views are wonderful from the formal terraces, looking out over the river Conwy across to the hills that lie between Bodnant and the Menai Strait. I have run out of superlatives, but Bodnant merits it.

Bodnant Gardens are currently stunning. Bodnant is always stunning, and it gets better every year. This time of year is one of its particularly shining moments, with the laburnum walk and the last of the azaleas, the rhododendrons in full bloom, the wisteria flowing like water, fabulous guelder rose (actually a viburnum), a few glossy camellias still in flower, some charming early roses, and enormous pieris shrubs the size of trees blooming with flowers that look like lily of the valley. These are complemented at ground level with some brightly coloured arrays of perennial flowers, glossy and eye-catching, even in the deep shade, where careful choices have produced fabulous results. The formal ponds were dignified and peaceful, whilst the bubbling brook at the bottom of the valley was utterly stunning, with birdsong and water over stones combining to create an audio-visual sense of peace and harmony that was really rather magical. Even the views are wonderful from the formal terraces, looking out over the river Conwy across to the hills that lie between Bodnant and the Menai Strait. I have run out of superlatives, but Bodnant merits it.

Although we had set out for Valle Crucis Abbey, just outside Llangollen, it was closed. I did not bang my head helplessly against the nearest wall, in spite of all the emails I have sent down the black hole of Cadw‘s multiple “contact” email addresses to find out when it would be open again. Instead we took out the road atlas and considered our options and Bodnant looked like a distinctly uplifting improvement on the day to date, particularly as we were planning to go next week anyway. The weather was a bit dodgy, but what the heck; we decided that the A5 was just down the road, and with a swift right turn onto the A470 at Betws y Coed we could be at Bodnant Gardens in no time – which is to say about 45 minutes from Llangollen. It was only noon, which gave us plenty of time to get there and spend the rest of the day wandering, especially if we returned to Dad’s in Rossett via the A55 dual carriageway and had a pub meal afterwards to avoid the need to cook (which we did). The weather improved all the time and by 4pm it was sunny, blue-skied, hot and perfectly gorgeous. In spite of a false start to the day, it became a marvellous day.

Although we had set out for Valle Crucis Abbey, just outside Llangollen, it was closed. I did not bang my head helplessly against the nearest wall, in spite of all the emails I have sent down the black hole of Cadw‘s multiple “contact” email addresses to find out when it would be open again. Instead we took out the road atlas and considered our options and Bodnant looked like a distinctly uplifting improvement on the day to date, particularly as we were planning to go next week anyway. The weather was a bit dodgy, but what the heck; we decided that the A5 was just down the road, and with a swift right turn onto the A470 at Betws y Coed we could be at Bodnant Gardens in no time – which is to say about 45 minutes from Llangollen. It was only noon, which gave us plenty of time to get there and spend the rest of the day wandering, especially if we returned to Dad’s in Rossett via the A55 dual carriageway and had a pub meal afterwards to avoid the need to cook (which we did). The weather improved all the time and by 4pm it was sunny, blue-skied, hot and perfectly gorgeous. In spite of a false start to the day, it became a marvellous day. Exiting through the gift shop, the eternal formula for visits these days, is given a slightly different twist to it, as not only is there a garden centre with some very healthy plants that were being snapped up by visitors, but a series of small Welsh craft shops. Within the garden centre there is a rather tatty coffee shop (although it did a good latte). There is also an official National Trust gift shop as you reach the exit. When you return to the car park via the new underpass, a much more upmarket café is available, which was well attended.

Exiting through the gift shop, the eternal formula for visits these days, is given a slightly different twist to it, as not only is there a garden centre with some very healthy plants that were being snapped up by visitors, but a series of small Welsh craft shops. Within the garden centre there is a rather tatty coffee shop (although it did a good latte). There is also an official National Trust gift shop as you reach the exit. When you return to the car park via the new underpass, a much more upmarket café is available, which was well attended.

Swallow mentions that Castletown Bridge, which carries the road across the stream between the two castles, “was probably the site of the medieval toll gate, catching people and animals entering Cheshire from Wales to the south and west, as Shocklach castle guarded the only road into Cheshire at this point.” Documentation suggests that a toll gate was present there

Swallow mentions that Castletown Bridge, which carries the road across the stream between the two castles, “was probably the site of the medieval toll gate, catching people and animals entering Cheshire from Wales to the south and west, as Shocklach castle guarded the only road into Cheshire at this point.” Documentation suggests that a toll gate was present there