Introduction

Birkenhead Priory is one of the most enjoyably unexpected places I have visited in the region, even more surprising than a Roman bath-house embedded in a 1980s Prestatyn housing estate. The priory site incorporates both the remains of the 12th century monastic establishment and the ruins of St Mary’s 1822 parish church with its surviving tower and terrific views. On all sides the site is surrounded by both heavy and light industry. Cammell Lairds shipyard not only butts up against the south and east walls, but purchased part of the priory’s former churchyard and cemetery for its expansion and the building of Princess Dock. On the other sides are warehouses and commercial units. The result is that in spite of the clanging and banging from the vast ship under construction immediately next door (fascinating in its own right), the obvious and somewhat inescapable cliché is that the ruins of the priory and parish church are an oasis of peace in the midst of all the busy activity. The small but quiet stretches of grass, the trees and the wild flowers contained within the remains of the priory site are a treat, and the splendid views from the top of St Mary’s tower are a powerful reminder of how the world has changed since the foundation of the priory.

I have divided this post into two parts, because there is so much to say. A visit to Birkenhead Priory is really five visits in one. In chronological order, a visit to the site provides you with the following heritage:

1) The priory, established in the 12th century and built of red sandstone, is the oldest part of the site and the star turn with its vaulted undercroft and chapter house

1) The priory, established in the 12th century and built of red sandstone, is the oldest part of the site and the star turn with its vaulted undercroft and chapter house- 2) St Mary’s parish church was built next to the ruins in 1821 to serve the growing community, its gothic revival windows wonderfully featuring cast iron window tracery

- 3) The priory’s scriptorium over the Chapter House, now with wood paneling over the sandstone walls, is the exhibition area for the Friends of the training ship HMS Conway,

- 4) The Cammell-Laird shipyard is hard up against the priory’s foundations and fabulously visible from St Mary’s Tower. When it wished to expand into the church’s churchyard, it purchased the land and re-located the burials

- 5) St Mary’s Tower, which is open to the public with amazing views from the top, is now a memorial to the 1939 HMS Thetis submarine disaster in the Mersey.

In this part, part 1 I am taking a look at the priory. In part 2 I have looked at the post-dissolution history of the site; the 1821 construction of St Mary’s parish church; the memorial to HMS Thetis and the display area for HMS Conway. I will tackle Cammell Laird’s separately, as I suspect that it will be very difficult to handle in a single post, and I need to do a lot more research before I make the attempt to summarize its history.

Birkenhead in the foreground with the manor and ruins of the monastery, and Liverpool in the background over the river, c.1767, showing just how isolated Birkenhead remained even in the 18th century. Attributed to Charles Eyes. Source: ArtUK

Foundation of the priory in the 12th Century

The priory was dedicated to St Mary and St James the Great. There are no documents surviving from the priory, and none of its priors became important in other areas of the church or in life beyond the priory, so most of the information comes from other sources of documentation as well as from the architecture itself. Its principal biographer, R. Stewart-Brown, writing in 1925, commented that it was “not possible to compile anything in any degree resembling a history of this small and obscure priory,” but the result of his work was an impressive overview of the priory, its financial stresses and its involvement in the Wirral as a whole and the Mersey ferry in particular. Much recommended if you can get hold of it. Although not certain, is thought that the priory was founded in the mid-12th century by one of William the Conqueror’s Norman followers who was rewarded for his service to the new king and the local earl Hugh Lupus with land on the Wirral. His name was Hamon (sometimes Hamo) de Massey from Dunham Massey, the second baron, who died in 1185, suggesting that the priory was founded before this date, probably in the middle of the 12th century.

Exterior of the west range, showing the two big windows that illuminated the guest quarters, the one on the left heavily modified.

The priory was established on an isolated headland, surrounded on three sides by water. Hamon almost certainly took as his model for the priory the abbey of St Werburgh in Chester (now Chester Cathedral) which was founded in 1093 by Hugh d’Avranches, also known as Hugh Lupus. Hugh Lupus had convinced St Anselm of Bec (later Archbishop of Canterbury and after his death canonized) to come and establish St Werburgh’s, and it was organized along classic Benedictine lines, about which more below. The founding of a monastic establishment was seen as a Christian act, a statement of piety and devotion, and was most importantly a precautionary investment in one’s afterlife, securing the prayers of the monks, considered amongst the closest to God, throughout the entire lifetime of the monastery

A priory was smaller and inferior in status to an abbey and was was often dependent (i.e. a subset) of an abbey, and answerable to it. It is possible that the much larger and infinitely more prestigious St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester supplied the monks to establish Birkenhead Piory, but there is no sign in the cartularies (formal documents and charters) of St Werburgh’s that there was any ongoing formal connection between the two. The difference between a non-dependent priory and an abbey was usually that the priory did not have sufficient numbers to be classified as an abbey, or that it had not applied for the royal stamp of approval required for the more senior status of an abbey. The minimum requirement for the foundation of a Benedictine abbey was 12-13 monks. A 16th century historian suggested that there were 16 monks, but it is by no means clear where this figure came from. Twice during the 14th century it is recorded that there were only five monks at the priory, and it is very likely that the priory remained too small to become an abbey.

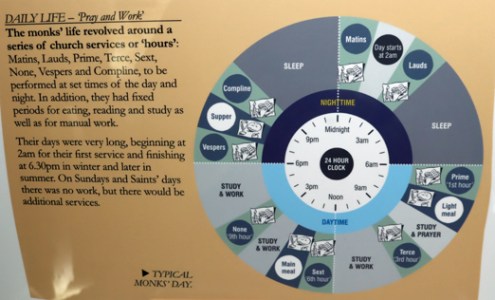

The typical monastic day in a Benedictine monastery. Not a great photo, but a very nice representation from a display in the museum area in the undercroft

The Benedictine Order was not the oldest of the monastic orders in Britain, but following the Norman Conquest it became the most widespread. It was named for St Benedict of Nursia who, in the 6th century, set out a Rule, or set of guidelines, for his own monastery. This spread widely and became the basis of many monastic establishments setting out to follow his example. The Benedictines had been well established in France at the time of the Conquest, and sponsorship by incoming Normans, granted land by William the Conqueror, ensured that they spread rapidly in England, and later Wales, Scotland and Ireland. Benedictine monasteries were all built to a standard architectural layout, with minor deviations, based on both religious and administrative requirements.

The monastic buildings

Plan of the Birkenhead Priory site. Source: Metropolitan Borough of Wirral leaflet (with my annotations in colour). North is left, south right.

If you take the guided tour, which I sincerely recommend, you begin your tour in the undercroft, now used as a museum / display space. Most helpfully it has a scale model of the priory with Stewart-Brown’s 1925 site plan, both of which help you to orientate yourself and get a sense of how the ruins were once a complex of buildings that defined and enabled a monastic community, combining religious, administrative, domestic and other functions. In the plan on the left, with the surviving remains of the priory outlined in red, the site of the priory church outlined in orange and remains of the 1822 St Mary’s Church outlined in green. The blue margin indicates the shipyard over the priory wall. The numbers on the plan are referred to in the description below. You can download a copy of the map (without the coloured additions) as a PDF here.

Like St Werburgh’s Abbey, the priory buildings were made of locally available red sandstone. Like all monasteries based on Benedictine lines, the monastic site plan began with a square. The bigger the monastery envisaged, the bigger the square. This was known as the garth (1 in the plan on the left), and was either a grassed area or a garden. Surrounding this was the cloister, a covered walkway that served as a link between the buildings that were erected around the garth, and where desks were usually arranged so that the monks could work. This was a secluded space, confined to the inmates of the monastery.

Model of the priory church and claustral buildings in the priory’s museum space in the undercroft showing a possible layout of the church. The chapter in this view is hidden behind the tower.

The most conspicuous of the buildings would have been the one that no longer stands: the church and its tower (4 on the plan above, outlined in orange), which made up one side of the cloister. Traditionally in Benedictine complexes this was built on the north side of the garth, making up an entire side of the cloister, in order protect the rest of the buildings and allow light into the garth and the other cloister buildings, but at Birkenhead Priory’s church was on the south, possibly to protect the claustral buildings from the winds whistling down and across the Mersey. The model and plan show that the 13th century church was built in the standard cross-shape. It featured a long nave at the west end (where the public were permitted to observe religious ceremonies), and a surprisingly long east end (where the ceremonies were performed) with two side-transepts, which were usually used as chapels for commemorating the dead and a tower over the crossing. A pair of aisles flanked the south and north transepts as show above. When it was first built in the 12th century, the church would have been much smaller and probably smaller than this footprint.

View of Birkenhead Priory by Samuel and Nathan Buck in 1726, showing the remains of the church’s northern arcade. Source: Panteek

The entrance to the chapter house with its Norman arches. You can clearly see the difference between the 12th century chapter house masonry and the 14th century scriptorium above with its gothic window and tracery. The tower in the background belongs to the 19th century church.

The chapter house (2) is the oldest of the Birkenhead Priory buildings, the only one remaining that dates to the 12th century. The building of the priory church, being the place where the main business of praising God took place, was usually started straight away, but the chapter house was often built in tandem as this was also of fundamental importance to a monastery. This is where the everyday business of the priory was attended to, from the day-to-day administration and disciplinary matters, to the daily readings of chapters of St Benedict’s Rules or other improving texts such as excerpts from one of the many histories of saints (hagiographies). The Birkenhead Priory’s original medieval chapter house is a gorgeous. The vaulted roof of the chapter house is superb (see the photo at the very top of this post), and although the windows have been altered over time, one of the deep Norman Romanesque window embrasures survives, and is a thing of real beauty (see below). The stained glass is all modern, but all are nicely done, the one over the altar by Sir Ninian Cowper combining religious themes relevant to the house (St Mary and St James flanking Jesus) with two prestigious characters from the priory’s own history (its founder Hamo de Massey and its two-time visitor Edward I). Gravestones from the medieval cemetery have been incorporated into the floor around the post-Dissolution altar. In the medieval priory, there would have been no altar in the chapter house, but following the Dissolution the chapter house was converted into a chapel and is still used for weddings, funerals and baptisms.

Over the top of the chapter house, a scriptorium was added in the 14th century. In theory this was where the copying of books took place, but it has been pointed out that this was a particularly large space for such an activity, and it may have been used for something else, or for a number of different activities. Today it is the display area for the training ship HMS Conway, and at some point in the 19th or early 20th century was provided with panelling and has some very fine modern stained glass by David Hillhouse. This modern usage will be discussed in part 2.

Opposite the chapter house the remains of the west range (7-11) survives, which was again a two-floor building separated into a number of different spaces It seems to have been divided into two, with the northern end and its big fireplace reserved for guests, and the southern end, with an entrance into the cloister, seems to have been split into two floors, with a fireplace on each, for the prior’s personal quarters, which would have included a private parlour that he could use for entertaining VIP guests. Although it’s not the most aesthetically stunning of the surviving claustral buildings today, the stonework displays a fascinating patchwork of different features and alterations that reflect many changes and refinements in use over time and are still something of a fascinating puzzle.

Opposite the chapter house the remains of the west range (7-11) survives, which was again a two-floor building separated into a number of different spaces It seems to have been divided into two, with the northern end and its big fireplace reserved for guests, and the southern end, with an entrance into the cloister, seems to have been split into two floors, with a fireplace on each, for the prior’s personal quarters, which would have included a private parlour that he could use for entertaining VIP guests. Although it’s not the most aesthetically stunning of the surviving claustral buildings today, the stonework displays a fascinating patchwork of different features and alterations that reflect many changes and refinements in use over time and are still something of a fascinating puzzle.

Remodelling in the 14th century created the undercroft and the refectory above it, as well as the kitchen. The undercroft (14), once used as a storage space, with the original floor intact. The investment in the lovely architecture may indicate that before it was used as a storage area, it had a more high profile role, perhaps as a dining area for guests. Above it was the refectory, unlike St Werburgh’s, Basingwerk Abbey or Valle Crucis Abbey, all of which had refectories at ground level. It was reached by a spiral stone staircase leads up to this space today.

The kitchen was apparently to the north of the west range, and connected to it, as shown on the above plan (12). This was convenient for the guest quarters, but not quite as convenient for the refectory over the undercroft, from which it was divided by a buttery (or store-room, 13), over which a guest room was also installed. The kitchen was apparently a stand-alone structure made mainly of timber, and this may have been because kitchen fires were so common, and building the kitchen slightly apart from the main monastery would have been a sensible precaution. Kitchen fires are thought to have been the cause of several devastating scenes of destruction in monastic establishments, spreading quickly via roof timbers and wooden furnishings.

The kitchen was apparently to the north of the west range, and connected to it, as shown on the above plan (12). This was convenient for the guest quarters, but not quite as convenient for the refectory over the undercroft, from which it was divided by a buttery (or store-room, 13), over which a guest room was also installed. The kitchen was apparently a stand-alone structure made mainly of timber, and this may have been because kitchen fires were so common, and building the kitchen slightly apart from the main monastery would have been a sensible precaution. Kitchen fires are thought to have been the cause of several devastating scenes of destruction in monastic establishments, spreading quickly via roof timbers and wooden furnishings.

Between the chapter house and the north range, which contained the undercroft and refectory, was an infirmary (19 on the plan) and the dormitory (18) side by side, each accessible from the cloister. The infirmary was for the benefit of the monks, and was where those who were sick or injured or suffering the impacts of old age were cared for.

Sources of income and financial difficulties

Carved head in the side of the fireplace in the guest quarters on the ground floor of the west range

Monasteries were amongst the most important land-owners in medieval Britain, on a par with the aristocracy. Their income came mainly from agricultural activities, both crops and livestock, as well as making and selling bread, beer, buttery and honey; but they might also own mills, mines, quarries and fisheries and the rights to anchorage, foreshore finds and the use of boats on rivers. For those with coastal and estuary locations with foreshore rights, there was, as Stewart-Brown lists, the benefits of flotsam (items accidentally lost from a boat or ship, jetsam (items deliberately tossed overboard), salvage from shipwrecks and keel toll. The luckier (or most strategically inclined) monasteries and churches also had pilgrim shrines, sometimes reliquaries imported from overseas. St John’s Church in Chester had a miraculous rood screen, St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester had the shrine containing the bones of St Werburgh herself, and Basingwerk Abbey had the neighbouring holy well of St Winifred. These attracted donations and bequests and were good for the settlements in which they stood, because the pilgrims needed places to stay, food and drink, and would probably buy souvenirs. Birkenhead Priory had no such shrine, but it probably felt the impact of the pilgrim route as the ferry crossing over the Mersey, which it ran free of charge, was an important link between Lancashire, west Cheshire and northeast Wales.

Some of the monastic landholdings on the Wirral. Source: Gill Chitty, on Merseyside Archaeology Society website

The original foundation of the monastery would have included both the land on which the monastery sat, funding for building it, and an economic infrastructure of landholdings as well as the income of some local churches. The long list of land-holdings sounds impressive, but most of them appear to have been quite small and scattered, some of which will have been wooded and some wasteland, not all of it suitable for cultivation or pasture. These include lands in Birkhenhead (including the home farm in Claughton with its mill), Moreton (with a mill and dovecote), Tranmere, Higher Bebington, Bidston, Heswall, Upton, Backford, Saughall, Chester, Leftwich, Burnden at Great Lever in Middleton, Newsham in Walton, Melling in Halsall, and Oxton. Either at foundation or not long afterwards, the priory was granted the incomes of the churches of Bidston, Backford, Davenham and half of the church of Wallasey, and claimed rights of Bowdon church that were disputed.

The monastery did not flourish with these assets. In spite of the claim that there were 16 monks at the time of its foundation, the records made by official church visitors suggests there were only a small number of monks at any one time (only five in 1379, 1381, and 1469, and seven, including two novices, in 1518 and 1524), and there is plenty of evidence to indicate that the priory struggled financially. Monasteries had significant overheads including feeding the community, buying tools and supplies, repairing monastic and farm buildings, appointing stewards and other employees, providing charitable alms and providing hospitality free of charge. Where they earned incomes from churches and chapels, they were also responsible for the provision of the clergy and shared part of the cost of maintaining the buildings. Ambitious priors often invested in building projects, sometimes to improve the monastic offering, sometimes for prestige, and even with donations this was usually costly. There were also occasional challenges to bequests made to churches from following generations, which involved costly legal proceedings. Balancing the books was a frequent problem for monastic establishments, and the priors of Birkenhead Priory were no different.

There were quite limited means by which the priors of Birkenhead might increase their income. The most obvious way of generating ongoing income was to acquire more land through gifts and bequests. In this endevour the priory probably had a real disadvantage in being near to both St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester and, across the river Dee, Basingwerk Abbey at Holywell. Both abbeys had significant land-holdings on the Wirral, and both had pilgrim shrines and were on pilgrim routes. Both were large and prestigious, and were far more likely to attract big gifts than a small and rather remote priory. If Birkenhead hoped to attract gifts of land, it probably had to depend on local landowners and merchants who felt a personal connection with the priory but would not necessarily have had the wherewithal to significantly change the income-earning potential of the priory, providing personal items rather than swathes of land. For these very local gifts and legacies, it is entirely possible that the priory was also in competition with contemporary parish churches on the Wirral. There are records in the early 16th century, not long before the monastery was closed during the Dissolution, that give an idea of the sort of bequests made by local people in return for requiem masses to be recited for their souls: one will provided a painting of the Crucifixion for the priory church. Another bequeathed the owner’s best horse, 10 shillings, and a ring of gold.

There were quite limited means by which the priors of Birkenhead might increase their income. The most obvious way of generating ongoing income was to acquire more land through gifts and bequests. In this endevour the priory probably had a real disadvantage in being near to both St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester and, across the river Dee, Basingwerk Abbey at Holywell. Both abbeys had significant land-holdings on the Wirral, and both had pilgrim shrines and were on pilgrim routes. Both were large and prestigious, and were far more likely to attract big gifts than a small and rather remote priory. If Birkenhead hoped to attract gifts of land, it probably had to depend on local landowners and merchants who felt a personal connection with the priory but would not necessarily have had the wherewithal to significantly change the income-earning potential of the priory, providing personal items rather than swathes of land. For these very local gifts and legacies, it is entirely possible that the priory was also in competition with contemporary parish churches on the Wirral. There are records in the early 16th century, not long before the monastery was closed during the Dissolution, that give an idea of the sort of bequests made by local people in return for requiem masses to be recited for their souls: one will provided a painting of the Crucifixion for the priory church. Another bequeathed the owner’s best horse, 10 shillings, and a ring of gold.

As the Middle Ages progressed, populations expanded and both new and old towns began to hold markets where everyday goods and more prestigious products could be traded, even once-isolated monasteries found themselves becoming integrated into the secular world and in competition with it. It certainly did not initially help the monks at first that during the early 13th century Liverpool began to grow. Under the Benedictine rules, monasteries had an obligation to provide hospitality to visitors when required, and the Birkenhead monks ran the ferry over the Mersey as a charitable service. When the priory was first established, offering occasional hospitality and running the ferry free of charge were not onerous. This changed rapidly after 1207 when Liverpool was granted burgh status by King John, as the following translation of the original Latin charter confirms (Translation from Picton 1884):

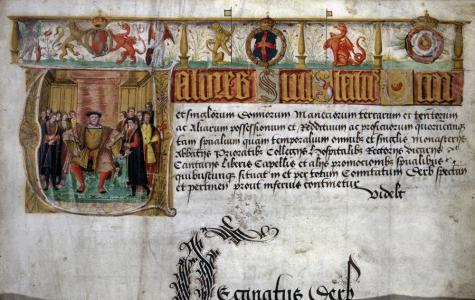

The 1207 charter of Liverpool by King John. Source: Royal Charters of Liverpool leaflet

John, by the grace of God King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy, Aquitain, and Earl of Anjou, to all his faithful subjects who may have wished to have burgages in the town of Liverpool greeting. Know ye that we have granted to all our faithful people who may have taken burgages at Liverpul that they may have all liberties and free customs in the town of Liverpul which any free borough on the sea hath in our land. And therefore we command you that securely and in our peace you come there to receive and inhabit our burgages. And in testimony hereof we transmit to you these our letters patent. Witness Simon de Pateshill at Winchester on the 28th day of August in the ninth year of our reign.

A little later Liverpool was granted the right to hold markets and fairs, and the links between Liverpool and the busy port of Chester grew to be increasingly important. There was no infrastructure to cope with this increase in human traffic. They were already offering a ferry service free of charge but even more pressing on their resources was the cost of housing guests. There were no inns between Liverpool and Chester (showing a lack of commercial ambition on the part of both Liverpool and Chester medieval merchants!), so the monks found themselves obliged to offer accommodation and food, which the rules of the Benedictine order required them to offer free of charge. This hospitality became particularly difficult if there was a spell of bad weather, during which those waiting to cross from Birkenhead to Liverpool would have to wait at the priory until the weather improved and crossings could resume. They were also were troubled with all the through-traffic that travelled along a route that ran through the monk’s Birkenhead lands close to the priory buildings.

It must have exacerbated the monks’ financial situation when Edward I visited the monastery twice with his entourage during this period. Edward’s first visit was in September 1275 for three nights, seeking a diplomatic solution to his dispute with the self-styled Prince of Wales, Llywelyn the Last of Gwynedd. His second was in 1277 for six days with the apparently dual motives of pursuing his campaign against Llywelyn and receiving a delegation from Scotland to settle a boundary dispute. Although the king would pay the costs of his entourage and horses, the cost of entertaining the king and his most senior advisors fell to the monastery. Hosting a royal entourage was notoriously expensive, and any contributions made by a visiting monarch to a monastic establishment only rarely compensated for the outlay.

One of the measures to improve their income in the 1270s involved the expense of serious litigation when incumbent prior claimed that the church had been presented in its entirety to the priory. This was disputed by the Massey family, who triumphed in the courts. Fortunately for the priory, in 1278 the 5th Hamon de Massey came to an agreement with the monks to their benefit. Other litigation occurred over pasture rights in Bidston and Claughton.

In 1284 the priory received permission from Edward I, who had probably witnessed the priory’s problems at first hand in the 1270s, to divert the road that disrupted the priory “to the manifest scandal of their religion” and to provide the priory court with an enclosure, either a ditch, hedge or wall, to preserve its privacy. This would have incurred costs, but would have eased one of the problems caused by the ferry. Rather more significant for their finances, early in the 14th century the priory was granted a licence to build and charge for guest lodgings at the ferry at Woodside, and in 1311 they were granted the rights to sell food there. It was at this time that the church was expanded, which would have been a significant project.

The first half of the 14th century had been hard for most of western Europe, with both famine due to anomalous weather conditions that caused crops to fail, followed only a few decades later by a plague that killed huge numbers of people. In Britain the famine lasted from 1315-17 and the Black Death arrived in 1348. The priory survived both the famine and the plague, as did the settlement of Liverpool, now a century old. At some point in the first half of the 14th century, the priory acquired land in Liverpool so that the monks could begin to trade their goods at market, building a granary or warehouse on Water Street (then known as Bank Street).

In 1316 the hospital of St John the Baptist in Chester was judged to be seriously mismanaged and was put into the hands of the priory, perhaps because of their experience running their own infirmary. This was a failure, merely adding to the priory’s problems, and was removed from their care in 1341.

Multiple layers in the west range, with a window added into the top of a former fireplace, blocking it, and a fireplace above it.

In 1333 Edward III requested monasteries to contribute to the expenses of the marriage of his sister Eleanor. Local monasteries who contributed included Birkenhead, which contributed £3 6s 8d and Chester’s St Werburgh’s Abbey which, bigger and more prosperous, gave £13 6s 8d. There were doubtless other payments of this sort, occasional and therefore unpredictable, and impossible to resist. The priory was also liable for taxation.

The ferry from Woodside had continued to be supplied free of charge, but the priory appealed to Edward III and was permitted for the first time to charge tolls in 1330, setting a precedent that remains today. A challenge to the monk to operate the ferry and claim the tolls, was challenged by the Black Prince in 1353, but the priory produced its charter and successfully resisted the removal of this privilege. The tolls charged were recorded at that time: 2d for a man and horse, laden or not; 1/4d for a man on foot or 1/2d on a Saturday market dasy if he had a pack

Other ways of generating income from lands to which they had rights were also explored, and from records of litigation against them, they were often accused of infringing forest law. Wirral had been defined as a forest by the Norman earls of Chester, which restricted how the land could be used. The monks were clearly assarting (cutting down wood to convert to fields and pasture), reclaiming waterlogged land, enclosing certain areas and cutting peat for fuel. The priory was able to argue special exemptions for some of the charges, and produced the charters to prove it, but at other times they were fined for the infractions. In 1357, for example, they were fined for keeping 20 pigs in the woods.

A number of monastic establishments seem to have responded to surviving the plague by redefining themselves via architectural transformations. Whatever the reasons for this trend, Birkenhead Priory was no exception and the 14th century could have been an expensive time for the monks. The frater range (including the elaborate vaulted undercroft and the refectory) was completely rebuilt and the west range was remodelled. The room today described as a scriptorium was also added over the chapter house at this time. Although Stewart-Brown suggests that much of this could have been accomplished with “pious industry . . . without much cost” with the assistance of donations of labour and money, that is probably somewhat optimistic, and there would have been an outlay. Certainly, at the end of the century the priory was considered to be so impoverished that it was exempted from its tax contribution.

A number of monastic establishments seem to have responded to surviving the plague by redefining themselves via architectural transformations. Whatever the reasons for this trend, Birkenhead Priory was no exception and the 14th century could have been an expensive time for the monks. The frater range (including the elaborate vaulted undercroft and the refectory) was completely rebuilt and the west range was remodelled. The room today described as a scriptorium was also added over the chapter house at this time. Although Stewart-Brown suggests that much of this could have been accomplished with “pious industry . . . without much cost” with the assistance of donations of labour and money, that is probably somewhat optimistic, and there would have been an outlay. Certainly, at the end of the century the priory was considered to be so impoverished that it was exempted from its tax contribution.

There is some evidence that for at least some of the Middle Ages the priory rented out land rather than working it themselves, except for their home farm at Cloughton. This had the benefit of providing a dependable income if tenants were reliable, and obviated the need to appoint managers or deal with labour and handle the sale of produce, but if the cost of living went up, the fixed income that no longer purchased what it had previously afforded, and this could represent a serious problem.

Dissolution

When Henry VIII’s demand for a divorce was rejected by the pope, the king severed Britain from the Catholic Church, creating the Church of England. This provided him with the opportunity to acquire land and valuable assets by dissolving all monastic establishments, all of which had been subject to the papacy. The spoils were to be used to fund Henry’s wars with France and Scotland, and some former monasteries were given to Henry’s supporters as rewards. To assess the potential of the monastic assets, Henry VIII commissioned the Valor ecclesiastis, a review of every monastery in the country. All monastic establishments with an annual income of less than £200.00 were to be closed as soon as possible. The first monasteries were dissolved in 1536 and the process was more or less concluded by 1540, with a handful of the more prestigious abbeys, like St Werburgh’s in Chester, converted to cathedrals. Birkenhead Priory was only earning £91.00 annually so it was amongst the first to be closed. There was no resistance by the Birkenhead prior, who was provided with a pension of £12.00 annually. The brethren were either dismissed or disseminated to non-monastic establishments.

Visiting

The car park is on Church Street, at the rear of the priory, where the cafe is also located. There is some on-street parking on Priory Street at the front of the priory. Source: Birkenhead Priory website

This is a super place, and makes for a terrific visit. Do go. You won’t be disappointed!

Even with SatNav, the big thing to remember about finding your way to Birkenhead Priory, if you are arriving by car from the Chester direction, is to do whatever it takes NOT to end up at the Mersey tunnel toll-booths 🙂 They were very nice about it, let me out through a barrier, and gave me perfect directions to get to the priory once they had freed me from the tunnel concourse. Very nice people. If Edward III was looking down, I’m sure he would have rolled his eyes in despair, given that it was he who gave the monks the right to charge for their Mersey ferry crossings.

Do check the opening times on the website, as the priory is only open on certain days and for only a few hours on those days, mainly in the afternoons. There is dedicated parking on Church Street at SatNav What3Words reference ///super.punchy.report. From there, the priory is up a short flight of steps. You can also park on Priory Street, which is where the SatNav will take you if you simply type “Birkenhead Priory” into your SatNav (at What3Words ///indoor.vibes.hips), which offers step-free access but there is limited parking there, and it is a favourite place for van drivers to park and eat their lunches so may be better used as a drop-off point before going round the the car park.

Remnants of the decorative floor tiles, now in the priory’s undercroft, which is used as a museum space

At the time of writing, a visit is free of charge, and so are the guided tours. My guide was the excellent Frank. He covered not only the priory but St Mary’s, the HMS Conway room, and the HMS Thetis memorial and, when I headed up to the top of the tower of St Mary’s, directed me to out for the dry dock where the CSS Alabama (the US Confederate blockade runner) was built by John Laird, to be discussed in Part 2. Frank was very skilled at providing sufficient knowledge to get a real sense of the place, but not so much that it became information overload. I very much appreciated this, having always found it difficult myself to strike that particular balance. I was lucky enough to have him to myself, having turned up at opening time, but I noticed that the next tour had a respectable group attending.

There is a small gift shop where you can also buy a really useful guide book with plenty of plans, illustrations and colour photographs. Please note that they are not able to take cards, and payment is cash only.

There is a small gift shop where you can also buy a really useful guide book with plenty of plans, illustrations and colour photographs. Please note that they are not able to take cards, and payment is cash only.

There are toilets in St Mary’s tower, a picnic area behind the undercroft on sunny days, and the highly rated Start Yard café is almost next door on Church Street.

For those with unwilling legs, I would suggest that apart from the tower and its 101 steps, and a flight of around 10 steps up into the scriptoruim (the display area for HMS Conway) this is entirely do-able. There are occasional single steps and uneven surfaces, and it is a matter of taking good care. As mentioned above, if you park in the carpark at the rear on Church Street, there is a flight of steps into the priory, but even if there is no space in the limited street parking available at the front of the priory on Priory Street, it is a useful drop-off point for anyone needing step-free access. You can find the SatNav references for both above.

I have posted a two-minute video of the priory, recorded on my iPhone, on YouTube:

Sources

Books, papers, and guidebooks

Baggs. A.P., Ann .J Kettle. S. J. Lander, A.T. Thacker, David Wardle 1980. Houses of Benedictine monks: The priory of Birkenhead, In (eds.) Elrington, C. R. and B. E. Harris. A History of the County of Chester: Volume 3, (London, 1980) pp. 128-132.

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/ches/vol3/pp128-132

Burne, R.V.H. 1962. The Monks of St Werburgh. The History of St Werburgh’s Abbey. S.P.C.K.

Chitty, Gill 1978. Wirral Rural Fringes Survey. Journal of Merseyside Archaeological Society, vol.2 1978

https://www.merseysidearchsoc.com/uploads/2/7/2/9/2729758/jmas_2_paper_1.pdf

de Figueiredo, Peter 2018. Birkenhead Priory. A Guidebook. ISBN 978 1 9996424 0 2

Hughes, Tony. St Mary’s Parish Church, BIrkenhead, 1819-1977. n.d.

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/wp-content/uploads/St-Marys-booklet.pdf

Picton, Sir James A. 1884. Notes on the Charters of the Borough (now City) of Liverpool. The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol 36 (1884)

https://www.hslc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/36-5-Picton.pdf

Stewart-Brown, R. 1925. Birkenhead Priory and the Mersey Ferry, and a Chapter on the Monastic Buildings. The Gift of the Directors of the State Assurance Company Ltd.

White, Carolinne 2008. The Rule of St Benedict. Penguin.

Websites

The Birkenhead Priory

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/

Buildings of Birkenhead Priory

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/about/

The medieval grave slabs of Birkenhead Priory

http://thebirkenheadpriory.org/wp-content/uploads/Graveslabs-of-Priory-Chapel.pdf

Mike Royden’s Local History Pages

The Monastic and Religious Orders in the Hundred of Wirral from the Saxons to the Dissolution of the Monasteries – A study of the Monastic history and heritage of Wirral by Norman Blake, April 2003

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/students/monasticwirral/monasticwirral.htm

The Influence of Monastic Houses and Orders on the Landscape and locality of Wirral (with particular reference to Birkenhead Priory) by Robert Storrie, April 2003

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/students/bheadpriory/bheadpriory.htm

The Medieval Landscape of Liverpool: Monastic Lands (with particular reference to the granges of Garston Hall and Stanlawe Grange) by Mike Royden, 1992

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/mikeroyden/liverpool/monastic/mondoc.htm

ArchaeoDeath

Commemorating the Reburied Dead: Landican Cemetery

https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2024/05/16/commemorating-the-reburied-dead/

Old Wirral

https://oldwirral.net/archaeology.html

Wirral Council

Making Our Heritage Matter. Wirral’s Heritage Strategy 2011-2014, 2013 Revision. Technical Services Department.

http://democracy.wirral.gov.uk/documents/s50009194/Wirral Heritage Strategy Appendix.pdf

Wirral History

Medieval Wirral (maps)

http://www.wirralhistory.uk/medieval.html

An online archive for for St Mary’s Church and the Priory, Birkenhead

History of the Priory and St. Mary’s Church Birkenhead

http://stmarysbirkenhead.blogspot.com/p/history-of-priory-and-st-marys-church.html

Leaflets

Birkenhead Priory Guide. Metropolitan Borough of Wirral.

Birkenhead Priory A4 leaflet Wirral

Liverpool’s Royal Charters

https://liverpool.gov.uk/media/ghdaoid3/liverpool-charter.pdf

St Mary’s Parish Church 1819-1977

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/wp-content/uploads/St-Marys-booklet.pdf