Introduction

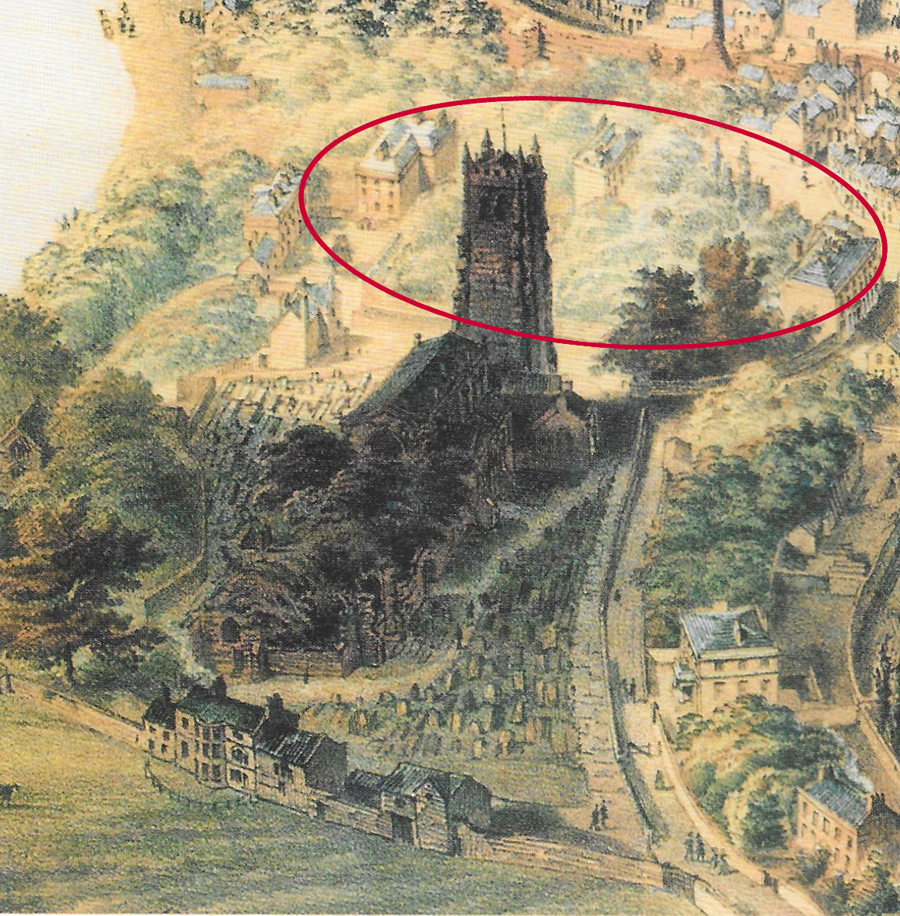

The tiny Grade-1 listed 12th century Church of St Edith (Historic England 1228322) is located just over four miles (c.6km) south of Farndon, retaining its lovely Norman arch. Together with its mellow red sandstone walls, the twin bellcote, and its small churchyard it has considerable charm and personality. It has been very well maintained, and a number of changes over the centuries were made, some later removed and some still in situ.

The tiny Grade-1 listed 12th century Church of St Edith (Historic England 1228322) is located just over four miles (c.6km) south of Farndon, retaining its lovely Norman arch. Together with its mellow red sandstone walls, the twin bellcote, and its small churchyard it has considerable charm and personality. It has been very well maintained, and a number of changes over the centuries were made, some later removed and some still in situ.

Although there are no signs that there was a village nearby, St Edith’s was built in the same period as the nearby twin motte-and-bailey castle at Castletown (see my earlier post here), and the two would have been part of the same set of community resources. Given the state of the castle now, reduced to simple earthworks, the survival of the church seems all the more impressive. It also probably served farms and hamlets in the general area, becoming the main place for regular get-togethers throughout the medieval period, particularly after the castle went out of use.

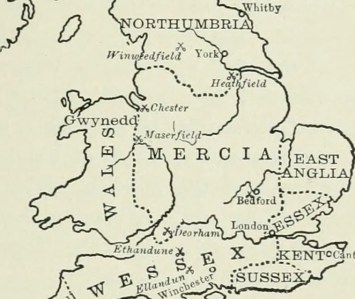

The biography of patron saint Edith is at best vague, but what is perhaps most interesting about her patronage is that she was an Anglo-Saxon saint, pre-dating the Norman Conquest (and the Norman arch), perhaps suggesting that the name was inherited from an earlier foundation on the same site. Edith (or Eadgyth, Eadida or Edyva) is thought to have been an illegitimate daughter of King Edgar who became a nun at Wilton Benedictine Abbey in Wiltshire. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints states that she was “conspicuous for her personal service of the poor and her familiarity with wild animals.” She died at the age of 23, and miracles at her tomb resulted in a cult following. Quite why she became a patron saint of a tiny rural church in west Cheshire remains unknown.

Building exterior

The Grade-II Norman arch is lovely, featuring chevron and cable designs, and was entirely in proportion to the Norman building. Each end of the arch terminates in a little sculptural element, each depicting a human head, both are very worn. Pevsner and Hubbard describe the arch as “very crudely decorated,” but the dismissive statement fails to acknowledge the considerable charm and authenticity of the ambitious archway on such a tiny church, as well as its determined fidelity to a particular stylistic paradigm. The main source of information about the church, Margery Waddams, who conducted research at the Chester Records Office, suggests that some of the upper chevron carvings may have been replaced.

The north wall is thought to date to the 13th century, although I have seen nothing to explain why the original wall might have been replaced. There is a single sculptural grotesque above the former entrance, now a window. Waddams suggests that there may have been a second Norman arch in the past in the south wall, due to the presence of “a small piece of chevron carving high in the south exterior wall which does not fit the present doorway.” The chancel was added in the early 14th century. An earlier arch is shown in the photograph above, although the date is uncertain.

Interior

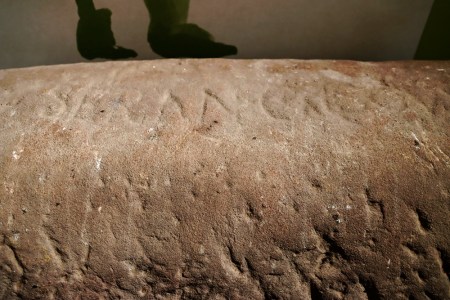

The interior consists of the original nave with a newer chancel on a slightly raised platform. Some of the structure undoubtedly belongs to the 12th century, and there is a single carving that may date even earlier. Located on one of the stone blocks of the north wall, close to where it meets the west wall, is an intriguing depiction of what appears to be a horse with a rider holding a shield. Although Waddams suggests that it was probably carved no earlier than the 17th century, the similarity to another carving at St Dochwy’s at Llandough, reported by George Bell in an issue of Country Life, may suggest an earlier date. The article led the church to contact the author, who confirmed that such carvings are very rare in Wales and and that he has seen no others similar to those at St Dochwys or St Edith’s. He points out that it could easily be an import from another site, and that it might (very tentatively) be as early as the 10th or 11th century in date. The matter remains unresolved.

In the interior, according to the Historic England listing, the north wall of the nave may be 13th century, the chancel arch, the east window and the north doorway are, according to Pevsner and Hubbard, all features of the 14th century, although Historic England places the chancel in the 15th century. Waddams points out that the top of the east window is missing, indicating that it has been cut to fit, suggesting either that it was taken down and refitted, or that it was brought from another church. The 15th century stone font is still in situ, but was re-cut at a later date, probably in the 17th century.

In the interior, according to the Historic England listing, the north wall of the nave may be 13th century, the chancel arch, the east window and the north doorway are, according to Pevsner and Hubbard, all features of the 14th century, although Historic England places the chancel in the 15th century. Waddams points out that the top of the east window is missing, indicating that it has been cut to fit, suggesting either that it was taken down and refitted, or that it was brought from another church. The 15th century stone font is still in situ, but was re-cut at a later date, probably in the 17th century.

Pevsner and Hubbard comment that “the odd west baptistery squeezed between the two buttresses looks a rustic c17 job” (Pevsner and Hubbard), a date also confirmed by Historic England. Also from the 17th century and the pulpit has part of the base of an octagonal pillar, marked with the date 1678 in brass-topped nails. Some of the pews in the nave date to around 1697.

Very endearingly, a pane of the east window is scratched: “I, Robert Aldersey, was here on 1st day of October 1756 along with John Massie and Mr Derbyshire. The roads were so bad that we were in danger of our lives”.

Very endearingly, a pane of the east window is scratched: “I, Robert Aldersey, was here on 1st day of October 1756 along with John Massie and Mr Derbyshire. The roads were so bad that we were in danger of our lives”.

The arced plaster ceiling over the nave is 18th or early 19th century, very attractively decorated with little rosettes. It slightly truncates the top of the original arch where it enters the chancel. The communion rail dates to the same period, as does the “table of commandments” in the chancel (with the abbreviation of Jevhoval, IHVH, mis-spelled as VHVH) and a “Credence table” that was installed on the site of a recess that had been walled up in the past.

A major restoration took place in 1878, including the addition of a wooden floor above the original beaten earth floor, which required the shortening of the wooden door under the Norman arch. Old high pews were replaced, and a gallery was removed. In 1887 the celebration of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee sounds like a real celebration (the Vicar Edward E. Hodgson quoted in Waddams): “Children and people marched to the Church with flags and banners of the Cross singing. Service was held at 2pm fully Choral. The Altar was decorated with 8 candles and 8 vases of flowers and floral cross, the windows with ferns etc. The Children returned to tea at 3pm. Adults had teat at 5. Then sports, dancing with Brass Band, closed a thoroughly enjoyable day.”

A major restoration took place in 1878, including the addition of a wooden floor above the original beaten earth floor, which required the shortening of the wooden door under the Norman arch. Old high pews were replaced, and a gallery was removed. In 1887 the celebration of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee sounds like a real celebration (the Vicar Edward E. Hodgson quoted in Waddams): “Children and people marched to the Church with flags and banners of the Cross singing. Service was held at 2pm fully Choral. The Altar was decorated with 8 candles and 8 vases of flowers and floral cross, the windows with ferns etc. The Children returned to tea at 3pm. Adults had teat at 5. Then sports, dancing with Brass Band, closed a thoroughly enjoyable day.”

Flanking the west end entrance to the babtistry, above the font, are the Royal Arms of George III, dated 1760, and the hatchment (funerary board) of one of the Pulestons, a local family, with their motto “Clarior es Tenebris” (More light out of darkness)

In 1903 two oak seats were presented to the church and placed in the chancel for the choir, whilst another six more oak seats were added to the nave.

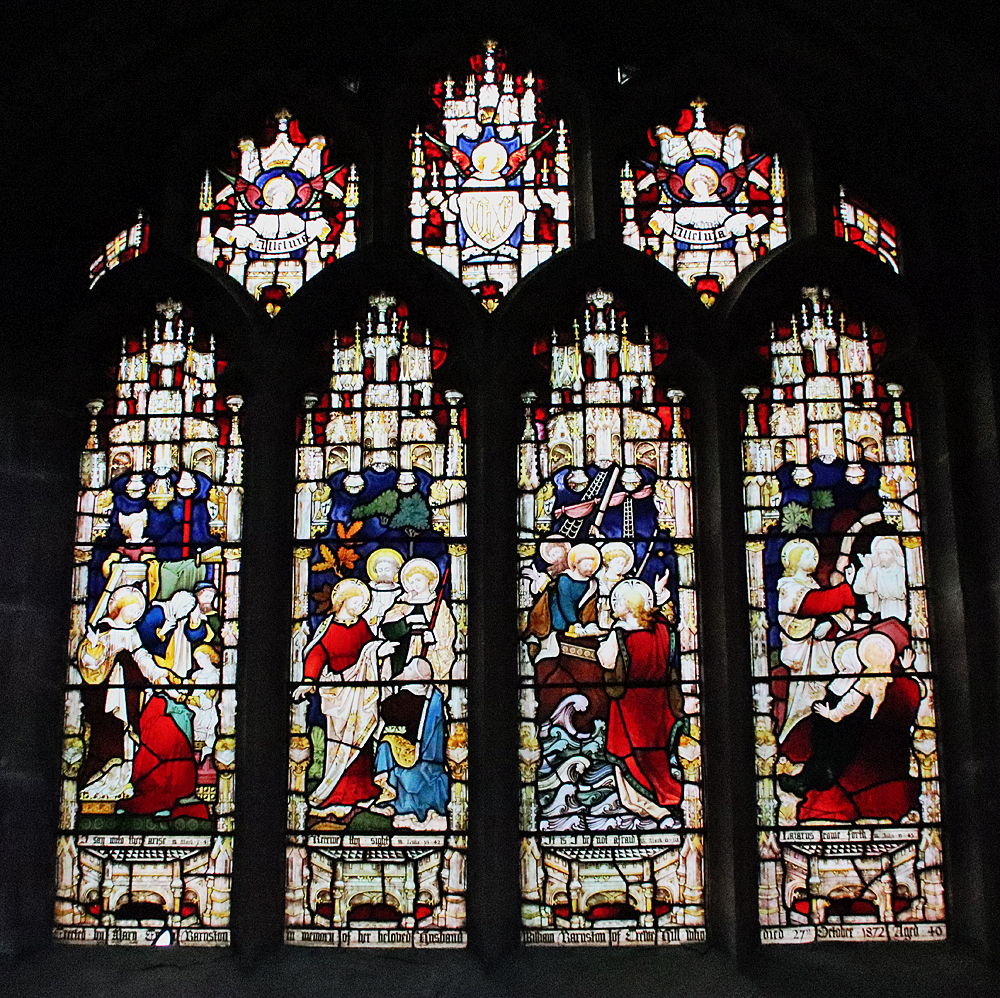

Another major restoration took place in 1974, during which the small semi-circular window with its geometric stained glass was added at the west end below the bellcote. To commemorate the year 2000 a new stained glass window was added to the north wall, directly opposite the Norman archway, based on the designs of children from the local Shocklach Primary School. At the same time a new lighting system and an audio loop were also installed.

The church continues to remain in use, and organizes events throughout the year, based on the religious calendar, including the rushbearing ceremony. In Pennine Magazine, Vera Adams describes the ceremony in the northwest:

Rushes have been used as a floorcovering for many centuries, and on certain feast days fresh rushes were strewn on the earth floors of churches.

A special festival, surrounding this ancient custom, grew up in the north west of England during the 17th century. In Lancashire, Cheshire and the Calderdale area of West Yorkshire, special rushcarts, pulled by a team of stalwart men, were used to distribute the rushes to the churches. The building of rushcarts developed into an elaborate ceremonial during the 18th and 19th centuries, and great rivalry grew up between the supporters and the builders of different carts. This was, at times, very intense and open brawls occasionally broke out, due, no doubt, to the amount of strong drink which was consumed. This led to some of the more puritanical clergy refusing to allow the rushbearers into their churches.

The two-wheeled rushcarts carried bolts or bundles of rushes built, very skilfully, into a tall pyramid, almost like thatching, on top of the carts. They were then decorated with flowers, rosettes, scarves, ribbons, tinsel and silverware. These trinkets were all loaned by local people.

See Sources for the entire article.

Churchyard

The churchyard has always fully surrounded the church, but was extended twice, in 1905 (consecrated in the same year) and 1922 (consecrated in 1993).

The churchyard has always fully surrounded the church, but was extended twice, in 1905 (consecrated in the same year) and 1922 (consecrated in 1993).

The Grade II listed red sandstone cross shaft and steps is missing its top, with the cross-shaft, presumably the victim of the two periods of 16th or 17th century iconoclasm. It stands on its original plinth of four steps. The lower three are made up of several blocks (the lowest of which is 7ft x 7ft square (2.13m), and the top one 3ft by 3ft (0.91m). A section removed from the top step was probably a kneeling platform. The shaft of the cross is octagonal. In the late 1890s it was found to be in a poor state of preservation as a memorial to the wife of the Reverend George Mathias, Esther Sophia. It was restored with a base piece 14×14 inches (0.35m) square and 11 inches (0.27m) deep. However, the idea was to restore it without succumbing to the temptation to make any attempt to otherwise improve upon it: “All this has been carefully done, no old stones having been misplaced, refaced, or in anywise injured.”

Oddly, there are only a handful of pre-20th century gravestones. I found none earlier than the 19th century, which include both table and chest types, the earliest dating to 1816. Most churches founded in the medieval period that have continued in use in this area will usually have some 18th century gravestones as well. Most of the the churchyard sloping away from the west end of the church is taken up with 20th century graves, dominated by the polished black style that remains popular in churchyards and cemeteries.

Visting

The church is not currently open to the general-interest public, although it is still a fully functioning church on a Sunday, but the exterior of the church with its Norman arch, charming bellcote and its peaceful churchyard makes for an enjoyable detour if you are in the area. It is at What3Words address ///initiates.recent.diamonds, or at the very end of Church Road, just off the B5069 to the right, a few minutes before you arrive at Shocklach village if you are heading north to south.

Sources

The main source of information for this post was Margery Waddams, who went through the church records and undertook research at the Chester Records Office.

The letter from Graham Bell concerning the north wall carving is shown in a frame in the interior of the church.

Books, papers and articles

Adams, Vera 1984. Rushbearing Revived. Pennine Magazine. Vol 5, No. 6, Aug/Sept1984

https://penninemagazine.wordpress.com/vol-5-no-6-aug-sept1984-rushbearing-revived/

Farmer, David 2011 (5th edition). Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford University Press

Haswell, George W. 1899. Shocklach churchyard cross. Journal of Chester Archaeological Society, Volume VI, part 2

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-2910-1/dissemination/pdf/JCAS_ns_006_02/JCAS_ns_006_02_163-166.pdf

Pevsner, Nikolaus and Edward Hubbard 1971. The Buildings of England: Cheshire. Penguin

Waddams, Margery 2015 (revised version). St Edith’s Church, Shocklach, Cheshire. Printed by St Edith’s Church and available to purchase on site (8 page booklet)

Websites

Based In Churton

Shocklach Motte-and Bailey Castle at Castletown

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/2021/09/14/shocklach-castletown-motte-and-bailey-castles/

Geograph

St Edith’s Shocklach

https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3064132

Historic England

St Edith’s Church

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1228322?section=official-list-entry

Medieval cross in St Edith’s churchyard

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1228350?section=official-list-entry

St Mary’s and St Edith’s (Tilston)

https://tilstonandshocklachchurch.co.uk/