Introduction

The Chuch is at left, the Chapter House opposite and the ground floor monks’ day parlour whcih once had their dormitory overhead. The line of the cloister, a covered walkway with arcades, and the central garth are marked out by the stone foundations

I have been to Basingwerk Abbey a couple of times, but never got around to writing it up. It’s a super site, and although it is now a ruin, it retains enough of its original structures to ensure that its layout is easily understood. St Winifred’s Well, with its lovely late gothic shrine, is only a mile and a bit away, and an important part of Basingwerk’s property for most of its life, will be covered on another post.

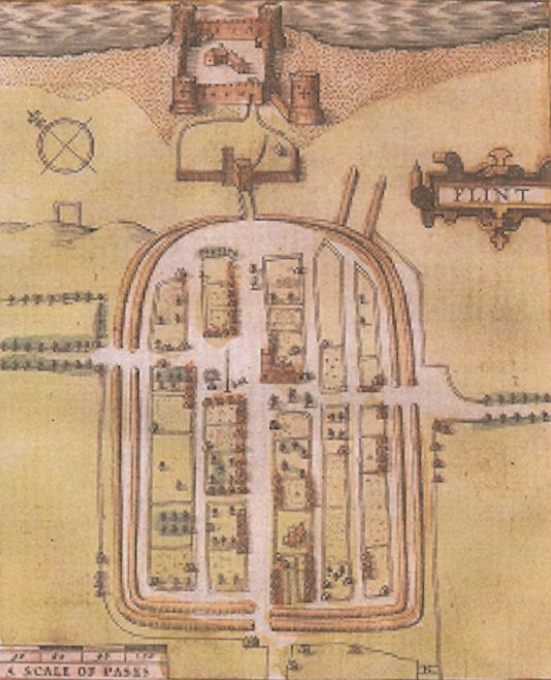

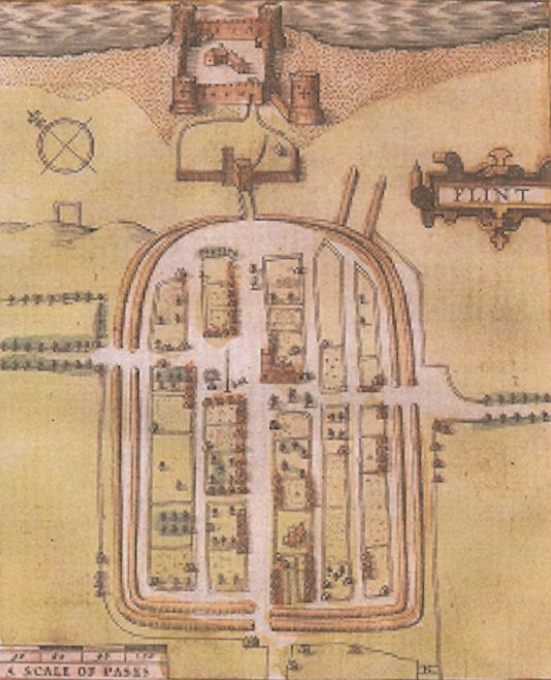

Basingwerk Abbey is only a few miles away from Flint Castle. The abbey preceded the castle by over a century but when Edward I founded Flint Castle and its accompanying town in 1277, the histories of abbey and castle became entwined. A visit to the abbey is easily combined with a look-in at the attractive riverside remains of Flint Castle. I have written about the history of Flint Castle on an earlier post.

Digital Aerial Photograph of Basingwerk Abbey. AP_2009_2896 – s, Archive Number

6355272. Source: Coflein

Savignacs and Cistercian Basingwerk Abbey

Remains of the church

The first Basingwerk abbey, dedicated to St Mary, was founded as a Savignac monastery Ranulf II (Ranulf de Gernons) (1099–1153), fourth earl of Chester and later merged with the Cistercian order. It is not known why the Savignac order was chosen by Ranulf, but the monks who were sent to Basingwerk were provided directly by the founding monastery of Savigny in southwest Normandy itself. It became Cistercian in 1147. Most of the monks who served there subsequently, up until the 15th century, were English, aliens in territory that was a bone of contention between England and Wales.

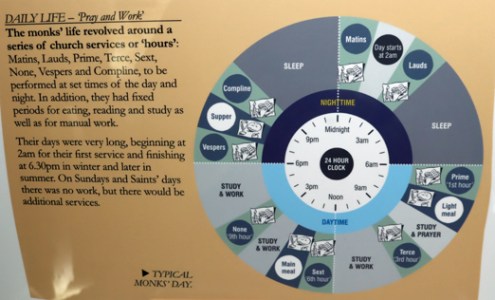

A monastic order is formed of a shared set of spiritual ideals, often spelled out in considerable detail in rules that covered everything from how many times a day a monk should pray, communally or individually, to where and when they could speak, eat and sleep, and what work they should engage in. All orders involved, at least in theory, a degree of renunciation and isolation by communities of monks, but these ideals were eroded as the influence of monastic houses grew. The trajectory of monastic history in Europe changed in the late 11th century and early 12th century with the establishment of the so-called reforming orders, who wanted a purer, less self-indulgent and more hard-working approach to cloistered living than other contemporary monastic institutions offered. The reforming orders believed that the Rule of St Benedict, as it had been originally conceived and set down in the 6th Century Italy, was the key to recovering a holier and more disciplined approach to a communal life of worship. The Carthusian order was established in 1084, the Cistercian order in 1098, the Savignac order between 1109 and 1112.

12th Century links between Cistercian monasteries.Although Citeaux, the node for all Cistercian abbeys, established early new bases in France, it was Clairvaux under the lead of St Bernard that was responsible for the earliest new abbeys in Wales. Of these Whitland was the most important for the northward spread of monasticism. The green lines emanating from Savigny reflect the Savignac order, which merged with the Cistercians after only 20 years, in 1147. So although Basingwerk in the north and Neath in the south were founded as Savignac orders, after 1147 they were brought under the rule of the Cistercians at Citeaux. Source: Evans, D.H. Evans 2008, Valle Crucis Abbey (Cadw).

In Wales one of the most successful of these orders was the Cistercian order, which left remains in north, mid and south Wales. Valle Crucis in Llangollen is the nearest of the Cistercian abbeys to the Chester-Wrexham areas, established in 1201, and is discussed in a series of earlier posts, which begins here with Part 1. The Savignac order is much less well represented throughout Britain, and the reason for this is that in 1147 it was amalgamated with the Cistercian order. Basingwerk Abbey, established as a Savignac monastery, became Cistercian in that year.

Because of their similarities the Savignacs and Cistercians were a good match, but there were differences too, largely in terms of the constitutional framework and systems of accountability. To ensure that these were understood after the fusion, Savignac monasteries were put under the supervision of an appropriately located and senior Cistercian order. Basingwerk was put under authority of Buildwas Abbey in Shropshire, which had also originally been Savignac. This was perfectly in keeping with the Cistercian hierarchical approach to monastic management with every new monastery answerable and accountable to a mother house. The mother house for the entire order was Cîteaux, and Clairvaux was the mother abbey for Whitland in south Wales, which was established by monks from Clairvaux itself. Whitland in turn established other abbeys including Strata Marcella near Welshpool, and this abbey in turn established Valle Crucis. This system created a network of houses that all linked back to the ultimate mother house at Cîteaux (Cistercium in Latin) in France, the founding monastery of the Cistercian order. Every Cistercian abbot had to return from his abbey to Cîteaux every year for what was known as the General Chapter, a great conference of the Cistercian abbots.

A more detailed history of monasticism, and the Cistercians in particular, is included in Part 1 of the series on Valle Crucis.

Cadw guardianship monument drawing of Basingwerk Abbey. Survey-plan. Cadw Ref. No. 216/9a4. Scale 1:192. Source: Coflein

The foundation and economic basis of Basingwerk Abbey at Holywell

Exterior of the refectory

The first Basingwerk Abbey was probably in wood, and was located at a different but nearby site possibly somewhere in the vicinity of Hên Blas in Coleshill, near a now-lost castle. There is a reference to a fortification in the Annales Cambriae describing how, when Henry II advanced into Wales from Chester, Owain Gwynedd prepared for the upcoming battle by digging a large ditch associated with a hastily built camp at a site called Dinas Basing. It is thought that this was the castle known to have been in the area of Hên Blas, which lies on a ridge between two streams and overlooks the Dee estuary. Excavations in the 1950s demonstrated the existence of a 12th century motte-and-bailey castle , which was flattened by Llewelyn the Great in the early 13th century, and was replaced with a defended courtyard with timber-framed buildings.

The central garth on a very moody day looking at the remains of the church. The tall upstanding ruin is the main remnant of the church at its east end. Photo taken from within the refectory

Basingwerk Abbey was later rebuilt in stone at the current site of the ruins, possibly in the 1150s, probably when Henry II granted a charter to the house and endowed it with the wealthy manor of Glossop in Derbyshire to assist with its financial future, 10 years after it became Cistercian. The general location seems to have been strategic rather than purely spiritual. The area of Tegeingl is located in the Four Cantrefs between the earldom of Chester and Welsh Gwynedd, always the subject of territorial dispute between England and Wales and a source of regional discontent until Edward I completed his invasion in the late 13th century. The establishment of a large French monastery was probably part of this process of establishing a presence, and a holy one at that. Although the monastery was later mainly populated by English monks, the Welsh too saw the benefit of patronizing a prestigious religious establishment and both Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (d. 1240) and his son, Dafydd ap Llywelyn (d. 1246) were benefactors.

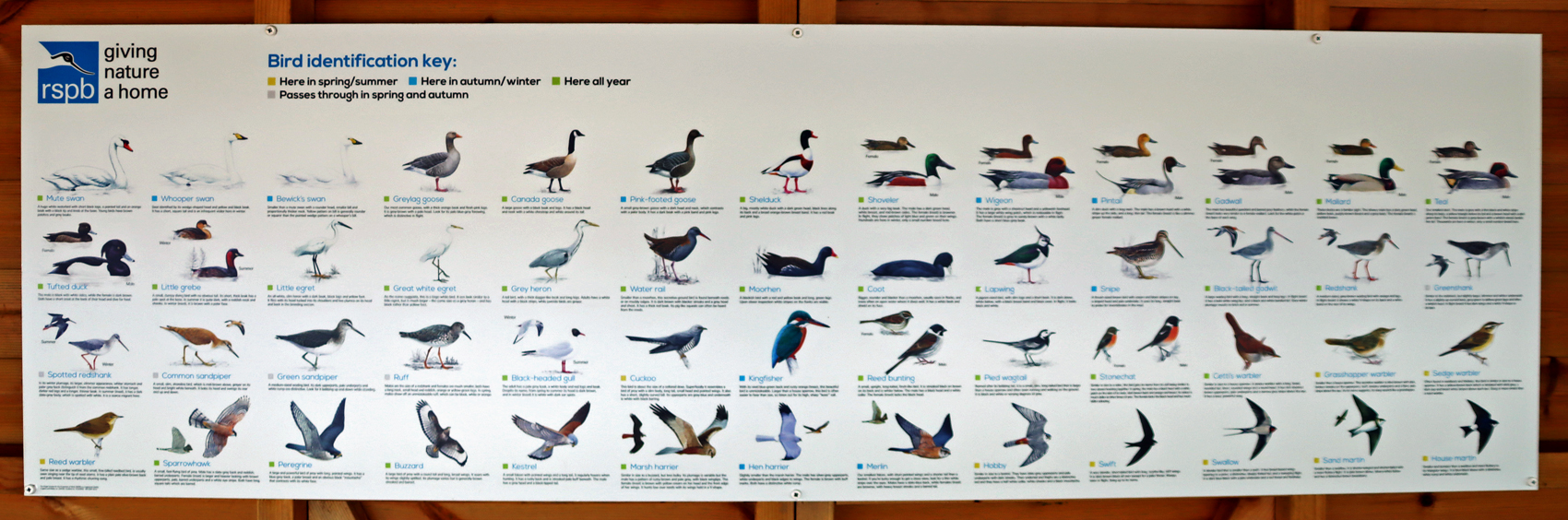

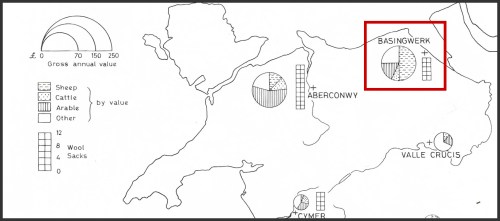

Detail of Map 12, page 91 in Williams 1990 showing Cistercian Lands in Wales, with those of Basingwerk marked in red. Click to enlarge.

When an abbey was founded, its endowment included a number of properties that included farmland or pasture that were intended to support it by the provision of produce to make it self sustaining and later by selling produce. Some of these could be quite substantial manors, but others were smaller farms, which the Cistercians referred to as granges. These could resemble mini monastic establishments and often had their own chapels. Later still, properties with their land could be rented out to tenants, but as late as the early 16th century, Abbot Nicholas Pennant was busy creating a new open enclosure in the mountains adjacent to the monastery apparently for agricultural development.

Gelli Chapel, from Thomas Pennant’s 18th Century Tour in Wales. Source: National Library of Wales, via Wikipedia

Based on the work of D.H. Williams in his 1990 Atlas, Silvester and Hankinson 2015 list all the known Basingwerk granges, shown on the above map produced by Williams. These were supplemented in 2001 by Williams in 2001. Apart from two properties in Derbyshire these are all concentrated in northeast Wales and the Wirral and include, in alphabetical order: Baggechurch /Beggesburch Grange, Bagillt; Calcot; Gelli Grange, either at Gelli or Gelli Fawr; lands in Whitford and the adjacent parish of Cwm; the Lordship of Greenfield, alias Fulbrook, including lands of Merton Abbot and party of Holywell town; and Over Grange, Holywell (all in Flintshire). Lands with uncertain boundaries have also been identified elsewhere in the area, including Mostyn, Wake, Flint and Gwersylt as well as transhumant pasture close to property belonging to Valle Crucis Abbey at Moelfre-fawr in Denbighshire, at Boch-y-rhaiadr and Gwernhefin. They also owned Lake Tegid at Bala.

Beyond Wales, there were also three granges on the Wirral: Caldy Grange (West Kirby), Thornton Grange and Lache Grange (known as “La Lith”), as well as the granges in Charlesworth at Glossop, their mos profitable property, and leased land in Chapel le Frith.

Over Grange, Holywell. Source: Williams 1990, plate 39, page 120. No indication of when the photograph was taken.

Of this list, only two buildings seem to have survived into relatively recent times, the remnants of two granges. A chapel at Gelli Fawr in Whitford (Flints), apparently once belonging to Basingwerk Abbey was recorded in a late 18th-century drawing which suggests that the chapel was part of a larger building complex. More can be found about the building and its possible function it in Silvester and Hankinson 2015. Another grange, Over Grange, was listed by Cadw in 1991, according to Silverster and Hankinson, and was located located to the southwest of the modern farm house, and has been much-altered. The photograph below shows it with small cross over the gable.

The Coflein website says that it is believed that Basingwerk Abbey originally constructed a windmill on this site, but the present structure probably dates to the late18 or early 19th century. Now restored. Source: Coflein 804658 – NMR Site Files. Archive Number 6259181

To support its farming activities, the monastery built watermills, windmills and fulling mills. Abbot Thomas Pennant (abbot from 1481 to 1522) appears to have been particularly active in the building of mills. Records indicate that there were at least four windmills, at least three watermills, and at least two fulling mills, as well as a tithe barn in Coleshill.

The site of the Holywell windmill is thought to be preserved by the surviving windmill that can be seen today, shown right. Two of the windmills were on the Wirral. Rowan Patel’s research has found that the Basingwerk windmill that stood at West Kirby area had been established at around 1152, and was probably upgraded and even replaced several times. It stood on a high spot near the coast, an ideally windy location, and eventually featured on sea charts as a major landmark for coastal navigation. It was mentioned in Henry VIII’s Valor Ecclesiasticus, the valuation of all monastic properties. Patel has found that after the Dissolution the mill became the property of the Crown and was rented to Thomas Coventree for an annual sum of 40s. Rowan Patel’s research suggests that the second Basingwerk windmill was at Newbold, east of West Kirby, mentioned in the Taxatio of Pope Nicholas IV in 1291, where a Newbold windmill was referred to and valued at 40s a year. Before the Dissolution it appears to have been rented out to Thomas Coyntre in 1525 on a 100 year lease at 40s a year. By the time of the Dissolution, Thomas’s son Richard Coventry was apparently paying rent to the Crown, and in 1659 William Coventry, presumably a descendant of Richard’s, was still paying rent. In 1664 it is next recorded having been sold to one Thomas Bennett in who donated it to the support of the poor. Patel notes that in 1546 two men stole oats, barley and pease worth 10d, indicating the cereals proposed at the mill in the mid-16th century if not before.

Watermills continued to have a value well into the 20th century, and medieval mills will have been replaced over time, removing the visible remains of them, particularly along the valley that ran down the hill behind St Winifred’s Well and past Basingwerk before emptying into the Dee.

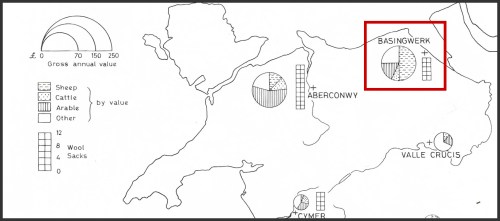

Economic Values excerpted from Williams 1990, map 21, p.105, showing the dominance of the agricultural contribution to the abbey’s income

Basingwerk had a large amount of livestock. The hills and newly cleared meadows around Basingwerk were ideal for sheep in the uplands and cattle in river valleys and pastures. The Welsh princes are also recorded as expecting two horses annually from Basingwerk which may indicate that the monks, like those of Cymer Abbey, were breeding horses.

As well as agriculture, which made up most of its income, Basingwerk was also involved in industrial activities, owning or leased industrial properties, Williams lists silver mining as a component of Basingwerk’s economic activities, and this is supported by Gerald of Wales whose trip through Wales in 1188 records leaving Conwy and heading east through Tegeingl through “a country rich in minerals of silver, where money is sought in the bowels of the earth” before spending the night at Basingwerk. The abbey was also involved in the salt trade, with salt extraction enterprises in Northwich and possibly Middlewich. Williams notes a coal mine leased from the Crown in Coleshill. Lead was also mined at Basingwerk, probably making use of the same resources that had been exploited by the Romans in the area.

Economic resources excerpted from Williams 1990, map 22, p.105

Timber was taken from woodlands in Penllyn in Merionydd for housing, hedges, fuel and other requirements, as well as for sale. Tenants were permitted to take a reasonable amount of firewood. Assarting, the removal of woodland for conversion to agricultural land and other uses was a common activity in the middle ages.

Fishing probably made up a significant part of the diet, as it did at most Cistercian monasteries. Basingwerk held the fishing rights for Lake Tegid at Bala, which it owned, and had a weir at West Kirby. Prince Dafydd granted them one fifth of the catch at Rhuddlan in the 13th century. They may also have purchased fish caught in the nearby coastal waters.

Basingwerk had a number of urban properties too, in Holywell, Flint, Chester, and Shrewsbury, which served as bases in town for the abbot and his representatives, which were probably loaned to friends of the monastery, but could also be leased out for additional income if required. The Shrewsbury house was probably a legacy of the abbey’s connection with Buildwas Abbey after the amalgamation of the Cistercian and Savignac orders.

The fan vaulting in St Winifred’s Well at Holywell

A major feather in the financial cap of Basingwerk was St Winifred’s shrine with its beautiful natural spring. The Holywell shrine of St Winifred was also another source of travelers requiring somewhere to stay and something to eat. St Winifred’s shrine was granted in 1093 to St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester, but was passed to Basingwerk in 1240, together with the living of Holywell church. An abbey with a pilgrim shrine had a whole world of opportunities for income generation, and St Winifred’s was not only famous in its own right for its powers of healing and provision of miraculous cures, but was on the pilgrim trail to Bardsey Island at the end of the Llŷn peninsula and Ireland, via Anglesey. In 1427 it was given a considerable boost when Pope Martin V granted indulgences for those visiting the shrine and giving alms to the chapel. Indulgences rewarded certain behaviours, like pilgrimages, with a remission of sins, meaning less time in purgatory. Royal visitors included King Henry V in around 1416 and Edward IV in 1461, helping to raise the profile of the shrine, which continues to welcome pilgrims today. It became even more attractive from the late 15th – early 15th century when the shrine was provided with a spectacular gothic building that surrounded the spring. I will cover Holywell in a separate post.

A traditional method of income acquisition for monasteries was appropriating a church and its income, sometimes to cover a particular expense, such as a major building project, and sometimes just to supplement income. The Cistercians officially frowned on this practice, but the ban on appropriating church incomes did not survive very long. Even so, Basingwerk had appropriated surprisingly few, just parish churches at Holywell, Glossop and a third at an unknown location, possibly to be identified with Abergele.

The fairs and markets granted to Basingwerk during Edward I’s reign in the 1290s are discussed below, and this must have been a considerable aid to their income.

Behind the monks’ day room and the dormitory above it was a block of buildings the function of which remains unclear. Suggestions include an extension of the abbot’s personal quarters, with rooms for special visitors, or a dedicated guest wing.

In spite of these various forms of income, Basingwerk sometimes found itself in financial stress. The monastery had been unable to provide a required payment to Edward III in 1346, and by way of explanation complained of the burdens of hospitality that came partly with being a Cistercian abbey, which put a great deal of emphasis on providing free hospitality, and partly from being near a major road, which had become increasingly busy after Edward I had moved forward into Wales, establishing market towns whose merchants moved between Wales and Chester for trade. Even later in its history, in the late 15th/early 1gth century, it was reported that guests were so numerous that they had to take their meals in two sittings. Smith paints an evocative picture of other travelers in Wales who “cautiously flitted from one English settlement to the next, seeking safe overnight bases where food and shelter could be found “in a land in which rumors of insurrection abounded.” Basingwerk was by no means the only abbey to complain of this burden, which was a particular problem for Cistercian abbeys, but was shared by any monastic community that sat at a busy location. Birkenhead Priory, which ran the ferry that allowed crossings between the Wirral and Lancashire for access to Chester and beyond (and later Liverpool), found itself in real difficulties due to the requirement to supply hospitality for ferry users who might be stuck at the monastery for several nights in bad weather.

A rather more specific problem was the expectation by the Welsh princes to use the abbey’s Boch-y-rhaiadr range for its annual hunting expeditions, during which the abbey was expected to provide bread, butter, cheese and fish for a hunting party of 300, expanding to 500, with money due in lieu when hunting did not take place. This was abolished by Edward I after his conquest of Wales.

The Cistercian monasteries in Wales were not exempt from all taxes, or subsidies, and some of the abbots and their community were employed as tax collectors. Other occasional charges were made on the abbey, such as a demand for financial contributions towards the marriage of Edward III’s sister. Basingwerk provided £5 in 1333.

The Cistercian monasteries in Wales were not exempt from all taxes, or subsidies, and some of the abbots and their community were employed as tax collectors. Other occasional charges were made on the abbey, such as a demand for financial contributions towards the marriage of Edward III’s sister. Basingwerk provided £5 in 1333.

The abbey, being so active in economic production in the Holywell-Flint areas, was responsible for the management of its lands and the personnel who managed and worked the land, but was also required to function in a judicial role, its courts administering justice and meting out punishments. Lekai says that the monastery had “a pillory, tumbrel and other instruments of punishment, although the penalty most often inflicted was a fine.”

The church is on the left and the two arches of the chapter house at right,. All the buildings were arranged around the central green area, the garth. The stone foundations for the covered and arcaded walkway survive.

Most of the Cistercian abbeys in Wales, at one time or another, had a diplomatic role acting as intermediaries between the Welsh princes and the Crown, acting for either side, a role that was in their political interests to accept. For example In 1241 Henry III used the Lache grange for a conference between himself and Prince Dafydd’s clerk. In 1246 Henry III chose the abbot of Basingwerk to escort Prince Dafydd’s wife Isabella from Dyserth Castle to Godstow nunnery near Oxford. A decade later, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffyd used an abbot of Basingwerk to carry a letter to Henry III.

In 1291 the Taxatio Ecclesiastica of Pope Nicholas IV valued Basingwerk at £68 8s 0d, gross value (compared with Valle Crucis at £91 8s 0d, and Margam at £255 27s 4½d). In 1346 it claimed that its lands were sterile, and it went through some bad years, but in spite of the rebellion of Owain Glyn Dŵr in the early 1400s and a very troublesome period when a monk took the abbacy without being legally elected in the first half of the 15th century, with a similar problem in the later 15th century, the appointment of Thomas Pennant in the early 16th century seems to have turned things around. In 1535, Henry VIII’s Valor Ecclesiasticus valued the monastery at £157 15s 2d. Margam by this time was valued at £188 14s 0d, and Valle Crucis £214 3s 5d.

——

The layout of the monastery

Plan of Basingwerk Abbey. Source: Robinson, D. M., 2006. Basingwerk Abbey (Cadw).

The remains of the monastery conform to a standardized layout favoured by all the orders that followed the rule of St Benedict, clearly shown on the Cadw plan to the right, which helpfully colour-codes the dates for each part of the building. Few parts of the 12th century abbey are left. Most date to the early 13th century, but the monk’s refectory was built in the mid-13th century. Much of the abbey was rebuilt in the 13th century, which was not unusual when, for example, a new abbot might want to make a mark, but in this case it is possible that much of not most of it was done due to damage inflicted during the wars between the English and the Welsh, when Edward paid compensation to the abbey to enable it to carry out repairs, about which more below.

The cloister arcade was apparently remodelled in the late 14th century. In the late 15th century Abbot Thomas Pennant carried out building work not only at the abbey but also at the shrine of St Winifred just up the road in Holywell. There are various aspects of the site where both date and function remain unclear. The western range, opposite the chapter house, would have been part of the original layout, used to house the lay brethren, discussed below, but may have gone out of use if a new use for them could be found when the lay brethren were no long featured in the community. Although the above plan shows that the possible guest accommodation is undated, timbers from fire damage Basingwerk were saved for future analysis and tree-ring dating shows that the felling-date of the crown-post truss was c. 1385. This is one of the earliest Welsh tree-ring dated. The dating was commissioned by Cadw.

The church is at left, the chapter house to its right, the day room and the windows of the first floor dormitory next, and set to the far right is the refectory

Although every monastery differed in some aspects, the basic template of buildings surrounding a central square area, a garth (green area) with surrounding walkway (the cloisters) with the monastic church making up one side, was a universal arrangement. The church was usually on the north side, as it was here, and often included two chapels in the transepts that flanked the crossing area where the choir was located. Some churches featured towers either above the crossing or at one end. The other buildings usually included a chapter house (the important monastic meeting room), day room with a dormitory on its first floor, a refectory, and sometimes an undercroft for storage. with an external door leading into the cloister on one side and the monastic precinct beyond. A sacristy was usually attached to the church, sandwiched between the church and the chapter house, which is how matters were arranged at both Basingwerk and Valle Crucis. The cloisters were usually supplied with desks (called carrels) along the exterior wall of the church where the monks could study and write.

The precinct, in which this arrangement of buildings sat, could include other structures like farm buildings, and visitor accommodation and often included a gatehouse, the whole surrounded by some form of boundary. A key feature of Cistercian monasteries was good drainage, which supplied the kitchens and fish ponds, where present, and took away toilet waste, and various parts of the Basingwerk drainage system can be traced at the site.

Part of the abbey’s drainage system

Part of the abbey’s drainage system

The church, with its entrance at far left and the south transept at right

Many of these features can be found at Basingwerk. The church is largely in ruins, but the layout is still visible in the very masonry walls that sit on the grass, including the columns that supported the roof and divided the church into a central nave with three aisles and seven bays, two side transepts each with a small transept and an eastern presbytery where the high altar would be located. At around 50 metres in length the church would have been one of the smallest Cistercian churches in Wales. Only Cymer near Dolgellau is shorter, at just over 30m in length. At the entrance to the presbytery a stone set into the floor may have supported a lectern.

What remains of the south transept, with the presbytery beyond

Basingwerk Abbey refectory wall

Opposite the former church, and one of the best preserved parts of the abbey, is south range with the refectory, which was built perpendicular to the cloister rather than lying along it on a north-south axis. The refectory in Chester Cathedral, the former St Werburgh Abbey, was built along the length of the cloister, limiting its size, but the the refectory at Basingwerk as limited only by the size of the precinct. This was probably a change introduced in the 13th century remodelling of much of the abbey, replacing a 12th century refectory that lay along the side of the cloister on an east-west axis. It is a substantial building with many features preserved in its walls. This includes the former entrance and stairway to the pulpit, now blocked off, from which religious texts would have been read during meals. S series of tall windows would have let in a lot of light, and there was a hatch between the refectory and the kitchen for the convenient handing over of food, as well as a cupboard, which was apparently shelved, opposite.

The monks’ day parlour at ground floor level, with the dormitory on the first floor, the windows suggesting the original height of this building

The east range of buildings, again along the edge of the cloister, extends between the east range and the church. As you face this range, running from right to left are the monks’ day parlour, over which was the dormitory, the length of which over-ran the cloister and ran parallel for a short distance with the refectory; a long thin parlour is next, and then most importantly is the chapter house, where the monks met daily to discuss the business of the order. To its left is the sacristy, which adjoined the south transept of the church.

The Chapter House

The sacristy to the left of the chapter house, with doorway leading into the church to the left.

Looking towards where the western range would have been located. The building beyond is now the café.

Opposite this range was the western range, of which there is almost nothing left. In a Cistercian monastery this was usually used, at least in the early decades, for the lay brethren. These were members of the monastic community who worked the land, and were not required either to be as educated as the monks, or to dedicate a similar amount of time to worship. They worked the land and were maintained by the monastery. As properties were leased out, the lay brethren were increasingly redundant and the western range was usually put to different uses. It is not known how it would have been used at Basingwerk.

Edward I and Basingwerk Abbey

Plan of Flint Castle. Source: Coflein

When Edward I settled on his location for his new castle at Flint, Basingwerk Abbey was just a few miles west of the new site. The monks of Basingwerk Abbey, which was established over 100 years earlier in 1132, must have wondered about the impact of the castle on their own security and their livelihood. During the first few months of the castle construction process in the summer of 1277 Edward stayed near Basingwerk. Edward saw himself as a religious man. He had been on crusade, and had made a vow to establish a monastic house of his own, under the Cistercian order, and had selected a site for it in Cheshire. Vale Royal Abbey was already underway in 1277 near Northwich, Edward having laid the first stone in early August. It seems unlikely that Edward was not often a guest of the Basingwerk Cistercian Abbey during the building of Flint, which apart from being obliged under Cistercian rules to provide hospitality, was unlikely to reject a royal visitor. Although Basingwerk had been founded by an English patron, Ranulf II it was probably more in tune with Welsh interests by the arrival of Edward. Indeed, earlier in 1277 seven Cistercian abbots had written a letter to Pope Gregory X supporting Prince Llewellyn ap Gruffud against charges placed by the Bishop of St Asaph, although the abbot of Basingwerk was not amongst them.

Drainage at Basingwerk, from the refectory

Whatever their personal leanings, it would have been very much in the interests of the order for good relations to be maintained. They may have offered advice about his plans for Vale Royal, and it is clear that some of the abbots in the Welsh-based monasteries, including Basingwerk, played an invaluable role as intermediaries between the Welsh and the English. Fortunately for the monks at Basingwerk, Edward I chose the Cistercian abbey at Aberconwy for his headquarters, forcing that monastic community to eventually shift further south along the Conwy valley to a new home.

The monks of Basingwerk would have been less than astute, however, if they had not regarded the new castle with misgivings, and if they had concerns about being caught in the middle of a fight between Edward and Llywelyn, their worries would later be justified. In the 1270s and 1280s the abbey suffered damage during the wars of Edward I, in spite of letters of protection issued to it in 1276,1278, and 1282 and in 1284 Edward granted £100 compensation to the monks after the army stole corn and cattle and the loss of workers who were abducted, presumably for labour. An additional 132 4d was paid in damages to churches in Holywell. Basingwerk was not the only abbey in the area to suffer and receive compensation. Valle Crucis near Llangollen received a sum of £160.00, and nearby Aberconwy was occupied by Edward I’s forces and its monastic community was forced to move to a new home to the south, at Maenan. Relations between the abbey and castle obviously continued to remain good, because when the castle was completed in 1280 a monk of Basingwerk was engaged as the chaplain to the royal garrison.

One of John Speed’s maps showing Flint Castle and town. The castle and town of Flint as mapped by John Speed in 1610, showing the original road layout and market place. Source: National Library of Wales

At Flint, Edward had established a Norman-style new town as part of his vision for colonizing various parts of Wales. This was an English settlement, and any new burgesses prepared to live there was given numerous incentives. In 1278 Edward granted it permission to hold weekly markets and an annual fair. In 1292 he granted Basingwerk the same permissions for Holywell, having granted them permission to hold an annual fair at their Glossop manor in 1290. The monks could charge market stall holders rent for the duration of the market, a nice source of income, as well as selling their own products. Basingwerk, with its water mills, windmills and fulling mills and land under both grazing and grain, was certainly in a position to sell a number of products, including grain, livestock and livestock products including meat, skins and wool. Welsh wool was recognized as being of very high quality, sometimes superior to even that of the better known wool produced by the Yorkshire monastic producers. The Taxatio ecclesiastica of Pope Nicholas IV in 1291 recorded that Basingwerk had 2000 sheep producing 10 sacks of wool, 53 cows (at a ratio of 37.1:1), and no goats. Even if it found itself in competition with Flint, Basingwerk’s fairs probably represented the opportunity to raise the abbey’s income. Its industrial products, as well as some of its wool, may have been sold for export.

The 14th – 16th century

Burton and Stöber describe how by the mid 14th century there were reports that the abbey was in debt, and in the fifteenth century some of its abbots were a distinct liability:

in 1430 the house was seized by Henry Wirral, who made himself abbot, and the following year he was engaged in a legal dispute for the office with Richard Lee. Despite the court ruling in favour of Lee, Henry continued in power at Basingwerk until 1454 when he was arrested for various misdemeanours and deposed. Matters did not improve, for in the following decade Richard Kirby, monk of Aberconwy, disputed the abbacy with Edmund Thornbar. Although the General Chapter ordered that Edmund be recognized as abbot, Richard was still in office in 1476.

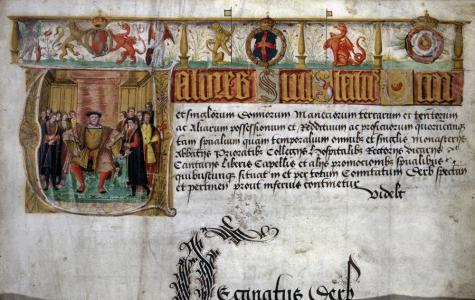

Fortunately the abbey’s fortunes improved under Welsh Abbot Thomas Pennant, who ruled the house for about forty years from around 1481 to 1523, although this was very much a last hurrah before Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries beginning in 1535. By the early 16th century Welsh bard Tudur Aled (died 1526) makes it clear that there was lead roofing and stained glass at the abbey. Tudur Aled praised Abbot Thomas , commending his his learning but also his generosity, generally an indication that they were being sponsored by a given abbot, as at Valle Crucis. Gutun Owain seems to have benefited from Basingwerk Abbey’s patronage. Owain is notable for having addressed over fifteen poems to Cistercian abbots, and is known to have stayed as a guest at Valle Crucis and Strata Florida as well as Basingwerk. Although the late fifteenth century manuscript known as the Black Book of Basingwerk (Llyfr Du Basing, now NLW MS 7006D, which was the mainly the work of Gutun Owain copied into a single volume) was probably held by Basingwerk at the time of the dissolution in around 1536, it is thought in fact to have been the work of copyist monks at Valle Crucis.

Thomas Pennant was not a man of undiluted virtue. In an order where celibacy was required and monks were not permitted to marry, Pennant not only fathered a family, but his son Nicholas, became the last abbot of Basingwerk, which in theory was an act of simony banned by the order. When the abbey closed, probably in 1536, with just three monks, Nicholas was the abbot.

St Mary on the Hill, Chester. Source: GENUKI

After the Dissolution every valuable object and piece of structural material was stripped for Henry VIII’s treasury. James says that part of the timber ceiling is at Cilcain, and that stained glass can be found at Llanasa. Burton and Stöber add that the choir stalls from the abbey were transferred to the church of St Mary on the Hill in Chester. Lead from the roof was removed, and may have been used for the repair of Holt Castle on the Dee and Dublin Castle. Williams adds that it may have been employed also in other crown buildings in Dublin, and that it is possible that the wooden sedilia in the parish church of St Mary, Nercwys, was from Basingwerk. There is a tradition that the Jesse window was reinstalled in the parish church of St Dyfriog (Llanrhaeadr-yng-Nghinmeirch) but this remains unconfirmed.

I have been unable to get access to St Mary on the Hill, a comprehensive history of which is on the Chesterwiki. It was decomissioned in 1972 and now describes itself as a Creative Space and venue for a range of activities. However, the Chesterwiki site says that the fittings, presumably including the Basinwerk choir stalls, were removed after the church was decomissioned, although it does not say where these fittings went.

From the 18th century the site attracted artists who recorded features that are now lost. In the early 20th century a large section of the south transept collapsed. In 1923 the site was put in State guardianship and in 1984 it was put into the car of Cadw.

Basingwerk Abbey miniature by Moses Griffiths, c.1778. Source: National Library of Wales, via Wikipedia

Final comments

Information about Basingwerk Abbey is fragmented and partial, but researchers have pieced together a history of the abbey that tells a story about abbey’s past, beginning as a Savignac establishment before being absorbed into the Cistercian network of monasteries. The disputes between the Welsh princes and Henry III and Edward I caused grief for the north Wales monasteries, but they survived to rebuild and move forward. Like other abbeys in Wales, the abbots of the abbey had a diplomatic role, often acting as intermediaries between Wales and England. As members of the wider community with an important economic role, the abbey was often involved in local judicial matters. Financial difficulties in the 14th and 15th centuries are recorded and but again the monastery survived these difficulties. In the early 16th century the abbey became a haven for Welsh bards, supporting their work. Throughout its history, its location on the main route through north Wales meant that it was obliged to provide more hospitality than more secluded monastic houses, whilst the shrine of St Winifred, whilst contributing to the prestige and financial value of the abbey, also required some management to prevent it becoming a drain on the abbey’s obligation to provide shelter and food. After the Dissolution in 1536, the abbey was decommissioned, its valuables removed and its properties either sold off our leased out. Today it is managed by Cadw and offers an excellent visitor experience.

Visitor Information

The site is free to visit. There is no visitor information centre but a small modern shop sells guide books, postcards and souvenirs relating to Basingwerk, St Winifred’s Shrine and the Greenfield Valley Park. The abbey’s postcode is CH8 7GH and the car park is on Bagillt road, just to the west of the enormous railway bridge, opposite a small trade/industrial estate.

There is a big car park at the foot of the abbey, shown to the right left on the A548, just west of the enormous railway bridge, which has a fairly gentle metalled incline up to the abbey, with a bench and information map half way up.

There is also a café just outside the main gates, which in October 2022 was doing a good coffee and a splendid lunch.

Basingwerk Abbey is a component part of Greenfield Valley Park, and is popular with dog walkers and children, so if you want a quiet visit it is probably best to go on a weekday outside the holidays. The rest of Greenfield Valley Park is an excellent visit in its own right, with a remarkable amount of industrial archaeology within its borders, and plenty of interpretation boards. I have posted about the industrial archaeology of the Green Valley Park here.

If you want to stay in the medieval period, St Winifred’s Well is about 1.5 miles through the park (shown as No.9 at the very top of the map right), or if you prefer to drive it has its own car park. Flint Castle is only 4 or so miles down the A548 towards Chester, and makes for a great visit. I wrote about the history of Flint Castle on an earlier post, Together, the three sites make a very fine medieval day.

Sources

Books and papers:

Burton, J. and Stöber, K. 2015. Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales. University of Wales Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qhdvn.13

Davies, Paul R. 2021. Towers of Defiance. YLolfa

Elfyn Hughes, R., J. Dale, I. Ellis Williams and D. I. Rees. Studies in Sheep Population and Environment in the Mountains of North-West Wales I. The Status of the Sheep in the Mountains of North Wales Since Mediaeval Times. Journal of Applied Ecology , Apr., 1973, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Apr., 1973), p.113-132

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2404720

Evans D.H. 2008, Valle Crucis Abbey, Cadw

Knight, L. Stanley 1920. The Welsh monasteries and their claims for doing the education of later Medieval Wales. Archaeologia Cambrensis, 6th series, volume 2, 1920, p.257-276

https://journals.library.wales/view/4718179/4728984/314#?xywh=-63%2C345%2C2942%2C1730

Rhys, Ernest (ed.) 1908. The Itinerary and Description of Wales with an introduction by W. Llewelyn Williams. Everyman’s Library. J.M. Dent and Co, London. and E.P. Dutton and Co (NY)

https://archive.org/details/itinerarythroug00girauoft

Huws, D. 2000. Medieval welsh Manuscripts. University of Wales Press

James, M.R. 1925. Abbeys. The Great Western Railway

https://archive.org/details/abbeys-great-western-railway

Jones, Owain, 2013. Historical writing in medieval Wales. PhD Thesis, University of Bangor.

https://research.bangor.ac.uk/portal/files/20577287/null&ved=2ahUKEwjxssbb0tvtAhWmxIsKHQgvBW0QFjAOegQICBAI&usg=AOvVaw2GbJiGy6Sl3SPiTX4K8RqZ

Lekai, Louis L. 1977. The Cistercians. Ideals and Reality. The Kent State University Press

Patel, Rowan 2016. The Windmills and Watermills of Wirral. A Historical Survey. Countyvise Ltd.

Robinson, D. M., 2006. Basingwerk Abbey. Cadw

Silvester, R.J., and Hankinson, R., 2015. The Monastic Granges of East Wales. The Scheduling Enhancement Programme: Welshpool. Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust (CPAT)

coflein.gov.uk/media/241/979/652240.pdf

Smith, Joshua Byron 2016. “Til þat he neӡed ful neghe into þe Norþe Walez”: Gawain’s Postcolonial Turn. The Chaucer Review, Vol.51, No.3 (2016), p.295-309

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/chaucerrev.51.3.0295

Williams, David H., 2001. The Welsh Cistercians, Gracewing

Williams, David H., 1990. Atlas of Cistercian Lands. University of Wales Press

Websites:

Coflein

Basingwerk Abbey

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/35649?term=basingwerk%20abbey%20holywell

Monastic Wales

Basingwerk Abbey

https://www.monasticwales.org/browsedb.php?func=showsite&siteID=24

Gutun Owain

https://www.monasticwales.org/person/72

The Black Book of Basingwerk

https://www.monasticwales.org/archive/24

Valle Crucis (Abbey)

https://www.monasticwales.org/browsedb.php?func=showsite&siteID=35

RCAHMW Exhibitions: Dendrochronology Partnerships

Bilingual exhibition panel entitled Partneriaethau Dendrocronoleg; Dendrochronolgy Partnerships, produced by RCAHMW 2013

https://coflein.gov.uk/media/200/524/rcex_026_01.pdf

RCAHMW List of Historic Placenames (searchable database)

https://historicplacenames.rcahmw.gov.uk/

University of Notre Dame

A Knight in St. Patrick’s Purgatory, by Haley Stewart. March 15, 2019

https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/a-knight-in-st-patricks-purgatory/

An Essay on Cistercian Liturgy by Dr Julie Kerr

Cistercians in Yorkshire, University of Sheffield

www.dhi.ac.uk/cistercians/cistercian_life/spirituality/Liturgy/Cistercian_liturgy.pdf

The chapter house propped up during excavations when M.R. James visited in 1925.

I have made a short visit to the estuary cycle track and walk in the past, simply to get a good look at the purported Iron Age promontory fort on Burton Point, but although it was enjoyable, it was a short stroll because the skies opened and I got drenched. Today, with no risk of rain, I decided to walk from Burton towards Parkgate, which I guessed to be about an hour’s walk each way. When I reached the “You are Here” board (with which the walk is dotted at key points) at Moorside, alongside Parkgate Spring and on the very edge of Parkgate, this was a full hour.

I have made a short visit to the estuary cycle track and walk in the past, simply to get a good look at the purported Iron Age promontory fort on Burton Point, but although it was enjoyable, it was a short stroll because the skies opened and I got drenched. Today, with no risk of rain, I decided to walk from Burton towards Parkgate, which I guessed to be about an hour’s walk each way. When I reached the “You are Here” board (with which the walk is dotted at key points) at Moorside, alongside Parkgate Spring and on the very edge of Parkgate, this was a full hour.

This first stretch of metalled lane is dominated by dog walkers and cyclists. Do keep an ear open for the cyclists as they can pick up a lot of speed along the lane and don’t always give a lot of notice of their impending arrival. The path goes through various changes. After some time it parts from the lane and becomes much more of a footpath with rough stone underfoot, which probably accounts for why the cyclists vanish from the scene at this point. At one stage it becomes a track across a field, although there is a route around this in wet weather that diverts inland for a while. The entire walk is well maintained with pedestrian gates and bridges where needed. One field had horses in it, so do take care if you are walking dogs.

This first stretch of metalled lane is dominated by dog walkers and cyclists. Do keep an ear open for the cyclists as they can pick up a lot of speed along the lane and don’t always give a lot of notice of their impending arrival. The path goes through various changes. After some time it parts from the lane and becomes much more of a footpath with rough stone underfoot, which probably accounts for why the cyclists vanish from the scene at this point. At one stage it becomes a track across a field, although there is a route around this in wet weather that diverts inland for a while. The entire walk is well maintained with pedestrian gates and bridges where needed. One field had horses in it, so do take care if you are walking dogs. Nearing Neston I spotted a line of vast red sandstone blocks extending out into the estuary vegetation, and a small spur of land also extends out at this point. An information board explains that this is part of the Neston Colliery, Denhall Quay. There is a particularly good book about the collieries, The Neston Collieries, 1759–1855: An Industrial Revolution in Rural Cheshire (Anthony Annakin-Smith, second edition), published by the University of Chester, which I read and enjoyed a few years ago. The sandstone blocks are massive, and as well as retaining original metalwork, one of them has become a memorial stone, as has one of the trees on the small spur of land. The line of sandstone, now a piece of industrial archaeology, is a very small hint of the extensive work that once took place here, but is an important one. The author of the above-mentioned book refers to it in a short online page here, from which the following is taken:

Nearing Neston I spotted a line of vast red sandstone blocks extending out into the estuary vegetation, and a small spur of land also extends out at this point. An information board explains that this is part of the Neston Colliery, Denhall Quay. There is a particularly good book about the collieries, The Neston Collieries, 1759–1855: An Industrial Revolution in Rural Cheshire (Anthony Annakin-Smith, second edition), published by the University of Chester, which I read and enjoyed a few years ago. The sandstone blocks are massive, and as well as retaining original metalwork, one of them has become a memorial stone, as has one of the trees on the small spur of land. The line of sandstone, now a piece of industrial archaeology, is a very small hint of the extensive work that once took place here, but is an important one. The author of the above-mentioned book refers to it in a short online page here, from which the following is taken: There are very few places to sit down along the walk, so I would recommend that if you need to rest your legs occasionally, you take your own portable seating. Regarding refreshments, I have mentioned Net’s Café, near the Burton end. I haven’t visited and apparently there’s no website, but it is just off Denhall Lane and it is listed on Trip Advisor here. There is also a very good pub called The Harp, which I actually have visited, with outdoor tables immediately overlooking the wetlands towards the Welsh hills, just outside Little Neston. The food being served there looked excellent, and I can give a solid thumbs-up for the cider. The pub was particularly well situated for my return from Parkgate as the zoom lens on my camera, a particular beauty that has been worryingly on the twitch for weeks, suddenly stopped working and was now, just to ram home the overall message, rattling. A glass of cider and a seat in the sun were perfect for jury-rigging the wretched thing so that the zoom now worked like an old-fashioned telescope and the camera’s autofocus, which was refusing point-blank to engage in conversation with the lens, could be operated manually on the lens itself. Sigh. New lens on order.

There are very few places to sit down along the walk, so I would recommend that if you need to rest your legs occasionally, you take your own portable seating. Regarding refreshments, I have mentioned Net’s Café, near the Burton end. I haven’t visited and apparently there’s no website, but it is just off Denhall Lane and it is listed on Trip Advisor here. There is also a very good pub called The Harp, which I actually have visited, with outdoor tables immediately overlooking the wetlands towards the Welsh hills, just outside Little Neston. The food being served there looked excellent, and I can give a solid thumbs-up for the cider. The pub was particularly well situated for my return from Parkgate as the zoom lens on my camera, a particular beauty that has been worryingly on the twitch for weeks, suddenly stopped working and was now, just to ram home the overall message, rattling. A glass of cider and a seat in the sun were perfect for jury-rigging the wretched thing so that the zoom now worked like an old-fashioned telescope and the camera’s autofocus, which was refusing point-blank to engage in conversation with the lens, could be operated manually on the lens itself. Sigh. New lens on order.