I have been visiting Dinas Brân on and off for decades, but have never got around to writing it up. It was one of my favourite walks with the family dog in the 1980s when my parents lived hereabouts. Much later, a regular return trip between Aberdovey and Rossett gave me the opportunity to see the castle from various different angles in all sorts of weather, the conical hill on which it sits soaring from the Dee valley providing a commanding, impressive position that dominates the landscape. I recently drove into Llangollen to go up to the castle on a hot day, prepared for a moderately steep walk from the canal bridge, correctly anticipating a slightly breathless arrival at the ruins.

This is a splendid walk. It is only about 2km (1.3 miles) from the Eisteddfod Pavilion, where I parked, although uphill all the way from the Wern Road canal bridge, so it feels longer, and the views towards the castle and back over the valley are splendid. The views from the castle itself are of course stupendous, both aesthetically and geologically. The geology and geomorphology are mentioned in brief below. More about parking, the different routes and conditions underfoot are towards the end of the post in Visiting.

This is a splendid walk. It is only about 2km (1.3 miles) from the Eisteddfod Pavilion, where I parked, although uphill all the way from the Wern Road canal bridge, so it feels longer, and the views towards the castle and back over the valley are splendid. The views from the castle itself are of course stupendous, both aesthetically and geologically. The geology and geomorphology are mentioned in brief below. More about parking, the different routes and conditions underfoot are towards the end of the post in Visiting.

Castell Dinas Brân, a Scheduled Monument, is the story of two fortifications, one dating to the Iron Age, at around 600BC, the other a medieval castle dating to the 13th Century. It is far from unusual to find Medieval castles built within the circumference of an Iron Age hillfort, because both were making use of the same strategic features: a good view of the surrounding countryside, a defensible position, often above cultivable land, and access to water. This post is about the Medieval castle.

xxx

History of Castle of the Crows

The medieval castle

Window of what was possibly the Great Hall of Dinas Bran

It is not certain which of the Powys Fadog rulers built Dinas Brân. The most common suggestion is that the castle was built by Prince Gruffudd ap Madoc (c.1220-c.1270), beginning in the 1260s, but there is an argument discussed by Paul R Davies that it may have been built by his father Prince Madoc ap Gruffudd Maelor.

Valle Crucis Cistecian Abbey, founded 1201

From c.1190 Prince Madoc was ruler of Powys Fadog, the northern section of Powys, which had been split into two on the death of Madoc ap Maredudd in 1160. He founded the nearby Cistercian abbey in 1201, and although his territory was comparatively small, he clearly had ambitions to establish his name and ensure his legacy, A castle would have been consistent with that intention, and as Davis points out, materials and workers could have been shared between the two sites. Prince Madoc died in 1236 leaving four sons, of whom Prince Gruffudd was the only one to survive. Whether Madoc started work on the castle or not, it is clear that Prince Gruffudd continued it, completing it well before the war of 1277.

Together with Powys Wenwynwyn to the south, Powys Fadog was sandwiched between the much larger territory of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s Meirionydd in the west of Wales and England to the east. Llywelyn (c.1223 – 11th December 1282, also known as Llywelyn the last, grandson of Llywelyn the Great) and his brother Dafydd (1238 – 3rd October 1283) had been in a long-term power struggle with Henry III that erupted once again under Henry’s son Edward I. Whilst the northeast territories provided a buffer zone between the two warring factions, their rulers were inevitably dragged into the question of where to bestow their loyalties. There was never any certainty that the members of a single family would throw in their lot with the same side, and some, like Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd, switched sides at least once.

Wales following the 1267 Treaty of Montgomery showing Powys Fadog sandwiched between Gwynedd and England. Source: Turvey 2002, p.xxvii map 8

Prince Gruffudd was married to an English wife, presumably for diplomatic reasons, providing a nod of friendship to the English. With Lady Emma Audely he had four sons, the eldest named Madoc, and one daughter. Presumably seen as fair game by Llywelyn, Powys Fadog was attacked. When Henry III was appealed to for help but did not come to Powys Fadog’s aid Gruffudd seems to have thrown in his lot with Llywelyn, arranging for peace between Meirionydd (Gwynedd) and the return of his territories by agreeing to the marriage of his eldest son Madoc to Llywelyn’s sister Margaret. Dinas Brân was apparently built in support of the interests of Llywelyn the self-styled Prince of Wales, borrowing certain elements of architectural styling from Llywelyn’s castles, including the D-shaped tower at its southern side.

Gruffudd apparently died in around 1270, because it was in this year that his sons signed a grant to provide Lady Emma with lands of Maelor Saesneg to secure her future. At this time ownership of the castle would have been split four ways between his sons, because primogeniture was the English but not the Welsh system of inheritance. Instead of one son or daughter inheriting an estate, on the death of a father all property was divided between the remaining sons, with provision usually made for wives and daughters. Each of Prince Gruffudd’s sons had his own decision to make in November 1276 when war broke out again between England and Wales. However they started the war, Gruffydd’s eldest sons eventually submitted to Edward, but in May 1277 an English force sent to take possession of the castle found it in engulfed in flames and it was evident that the garrison left behind had remained loyal to Llywelyn. The decision to burn and abandon the castle rather than defend or surrender it did not, however, completely destroy the castle.

After the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1277 Llywelyn paid homage to Edward, sitting to the left of the king’s throne, with Alexander of Scotland at the king’s right. The peace did not last.

After the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1277, Llywelyn’s power was confined to northwest Wales. The English inspection of Dinas Brân to assess the damage caused by the fire found that although considerable superficial damage had been inflicted, the well-built castle was structurally sound and still of strategic value. Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, wrote to Edward I recommending that the castle be repaired and garrisoned with English troops.

Following Edward’s triumph, Powys Fadog was abolished as a territory. Edward gave ownership of the castle and all its lands to John de Warenne, the early of Surrey. The castle, however, was no longer relevant as a symbolic stronghold of the former territory and now stood at the borderland of the new friendly lordships of Chirk, held by Roger Mortimer, and Bromfield and Yale by John de Warenne. Instead of devoting any attention to Dinas Brân, de Warenne became busy building his new castle at the eastern end of Bromfield and Yale on the Dee crossing at Holt near Chester.

Ruins of Dinas Bran

There is no record of the role performed by Dinas Brân, if any, during the final great conflict between Llywelyn and Edward of 1282, when the English were triumphant. Llywelyn died on the battlefield that year, and Dafydd was captured and put to death in 1283. As Holt Castle grew, Dinas Brân was abandoned.

A completely unsubstantiated legend concerns the fate of the two underage sons of Prince Madoc, Gruffudd’s eldest son. Walter Tregellas in 1864 tells the story, in which Edward I conferred guardianship of the two boys on Roger Mortimer and John de Warenne: “it is stated that the two children were soon afterwards drowned under Holt Bridge . . . This is said to have happened in 1281.” He goes on to recount an even better version of the conspiracy, however: “it is uncertain whether the king himself did not cause the children to be put to death.” There is no evidence whatsoever about what became of the two younger children of the prince of Powys Fadog.

Dinas Bran and the wonderful scenery beyond

The only hint that they castle buildings may have been re-used is a poem by Hywel ab Einion Llygliw Myfanwy Fychan in the 14th century, in which he claimed to have been rejected by the beautiful girl who lived there. There is no evidence to support this later domestic occupation, but neither is there anything to deny it. John Leland, visiting in 1536, found it in ruins.

The Victorians

Dinas Brân Castle by Alphonse Dousseau, c.1850. Source: The National Library of Wales, via WikiData.

When ruins became desirable romantic destinations, Dinas Brân was an obvious lure for painters (many of whom chose to paint safely from below) and more adventurous tourists. The Holyhead road was the major route through north Wales, with Telford’s great route, now the A5, opening in 1826, and the railway was opened in 1864. A local entrepreneur, demonstrating great faith in the spirit of adventure demonstrated by the new tourists, decided to make the most of the popular site and the first visitor provision was supplied in 1820, with a cottage added in the 1880s as a tea room together with an octagonal camera obscura, which was still in situ by the start of the Second World War.

Walking up the hill not far from the summit I found a piece of slender white clay pipe, about an inch long, on a piece of well-worn hillside. This almost certainly belonged to the period of Victorian interest in the castle.

Victorian cottage built for serving teas to visitors on Dinas Brân. Source: People’s Collection Wales

The castle as it stands today

Fieldwork

Plan of Dinas Brân, both prehistoric and medieval, following the geophysical survey of 2017

There has been very little fieldwork at Dinas Brân, and even the antiquarian investigators who explored other sites seem to have felt that this was one challenge too many. The only exception appears to be alocal treasure hunter who is mentioned in a journal entry by Lady Eleanor Butler of Plas Newydd, whose home was in full view of the castle, and who commented that their landlord had informed them that a smith from Dimbraneth “has been dreaming of more than a year past of treasure at Dinas Brân. Hew has within this week begun to dig.” There is no report of any discoveries.

In 2017 a geophysical survey was carried out and this was quite comprehensive, addressing both the medieval castle and the prehistoric hillfort. Although nothing conclusive was discovered, magnetic readings did suggest that a fire had scoured the ramparts, perhaps tying in with contemporary reports that the sons of Prince Gruffudd had set fire to the entire structure rather than surrender it to the English.

In 2020 a survey was carried out by the Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust (CPAT) to assess the condition of the site, both the castle and the prehistoric hillfort, making recommendations to make it safer and more approachable for visitors and to manage archaeological impact. Earthworks were noted beyond the hillfort but were not included in the survey.

CPAT excavation at Dinas Brân in 2021. Source: Heneb

It was not until August 2021 that the first archaeological investigation was carried out at the site, organized by CPAT. It was a small exploratory dig, with four trial trenches both within and outside the castle walls. The main aim of the project was less investigation of the history and more about assessment of the condition of the building’s foundations. Although the excavations did no more than reveal the medieval floor surface, one sherd of medieval pottery was recovered and a “ledge/kerb was discovered projecting from the gatehouse wall, with a portcullis slot in it near the east end, and a fine masonry carved pillar base at the western end.” In 2021 the Heneb report said that the excavation report was “awaiting a second phase of work in 2022,” but I have been able to find nothing about a 2022 excavation and no further reports.

Modern conservation work was carried out by Recclesia, who surveyed the site and inserted stabilizing rods into the south wall of the castle to ensure that it stays upright now and in the future.

The surviving architecture

Detail of an old interpretation board

The plan drawn by Tregellas in 1864. with annotations

The castle was very fine in its day, with imposing fortified walls and stone and timber buildings. There are hints that there were decorative features. I have annotated the plan drawn in 1864 by Walter Tregellas to make this easier to follow. If you have walked up from Llangollen, and climbed the east-facing slope of the hill, you will have entered opposite the original entrance. I had had a long wander around before tackling how the ruins relate to the original layout but when I got stuck into the site plan, I started at the entrance.

The ditch surrounding the castle

The site consists of a rectangular court orientated east-west, c.82m by 35m, surrounded by a ditch dug out of the bedrock, which provided the material from which the castle was built. As well as building materials available within the immediate vicinity, it was found that there was sandstone facing in certain parts of the castle, which would have provided it with both refinement and prestige. It is not clear where this came from, but it is likely that it was sourced from the same location as the Valle Crucis ashlar. The ditch surrounding the castle was an impressively deep and wide feature, running around three sides, the northern side of the castle being positioned directly over a steep drop. At the southwestern corner of the ditch was once a well, the location of which is now very difficult to see.

An artist’s impression of how the gatehouse (right) and the keep (left) as they may have looked when it was first built. Source: Clwydian Range and Dee Valley

The original entrance was marked by a gatehouse that, being one of the points of weakness of the castle, was built so that it could be well defended, with twin English-style towers forming a gatehouse, each with hollow basements and, remarkably, appears to have been furnished with highly ornate rib-mouldings. This is unprecedented in Welsh castle design and may have been copied from an English example. One of the two gate towers still has the underfloor barrel-vaulted arch that was accessible from the courtyard; although it is now open to the outside, this would have been closed in the 13th century and is probably the enlargement of an arrow slit. The vaulted room is closed to the public except on special open days. The gatehouse was supplied with latrines on its northern side, that emptied down the walls into the ditch.

The vaulted undercroft in the gatehouse

The stairwell that lead up to the first floor of the keep

Heading clockwise from here, you encounter the square keep. This was once an impressive building that helped offer protection for the gatehouse as well as the most vulnerable eastern approach. It will also have provided a home for the main family members and a final retreat at a time of siege. It was equipped with latrine which, like the gatehouse, emptied into the ditch. Additional security was provided for the keep. It could only be entered via a first floor door reached by stairs from a walled passage, and was separated from the rest of the castle interior by its own ditch, which would have been crossed by a liftable bridge.

Continue around to the right to follow what was once the long south curtain wall. The section of wall with two giant openings in it was either the site of the castle’s Hall, where dining and socializing would have taken place, or its chapel. The two openings, providing plenty of light for interior, would have been about 1.8m (6ft) wide at their maximum width. They would have had shutters to protect the castle from the elements, but no window glass.

At the far end of the Hall a doorway opened into a D-shaped tower that extended beyond the line of the curtain wall. The D-shaped section has gone, but this tower was a major feature of the castle, rising to two if not three floors. A good surviving example can be seen at the well known Ewloe Castle (about which I have posted here). Again, this was a defensive measure providing archers good views over the ditch and the flanking walls. The ruins of the inners walls give a sense of the size of this half of the room. It is likely that part of this was used for the castle kitchens, which gives weight to the argument that the adjoining apartment was the dining hall rather than the chapel.

Further along this stretch and you will find yourself looking out between two sections of wall, a gap that represents the remains of the postern gateway. As well as providing a useful secondary pedestrian entrance on the opposite side of the castle from the main gatehouse, this could also be used as a “sally port” that would allow foot soldiers to mount a surprise attack from an unexpected position.

A rectangular building at the west end may have been either the hall or the chapel or served another purpose. This area is likely to be highly disturbed, archaeologically, due to the Victorian building works in this area. The rest of the interior would have been filled with timber-built buildings, including accommodation for servants, storage, stables and workshops.

The landscape

xxx

British Geological Survey geological timeline.

Standing on the peak of the hill, you are 305m (c.1000ft) above seal level. Geologically, Llangollen is divided into two main formations. At the top of Dinas Brân you are standing on one and looking at the other.

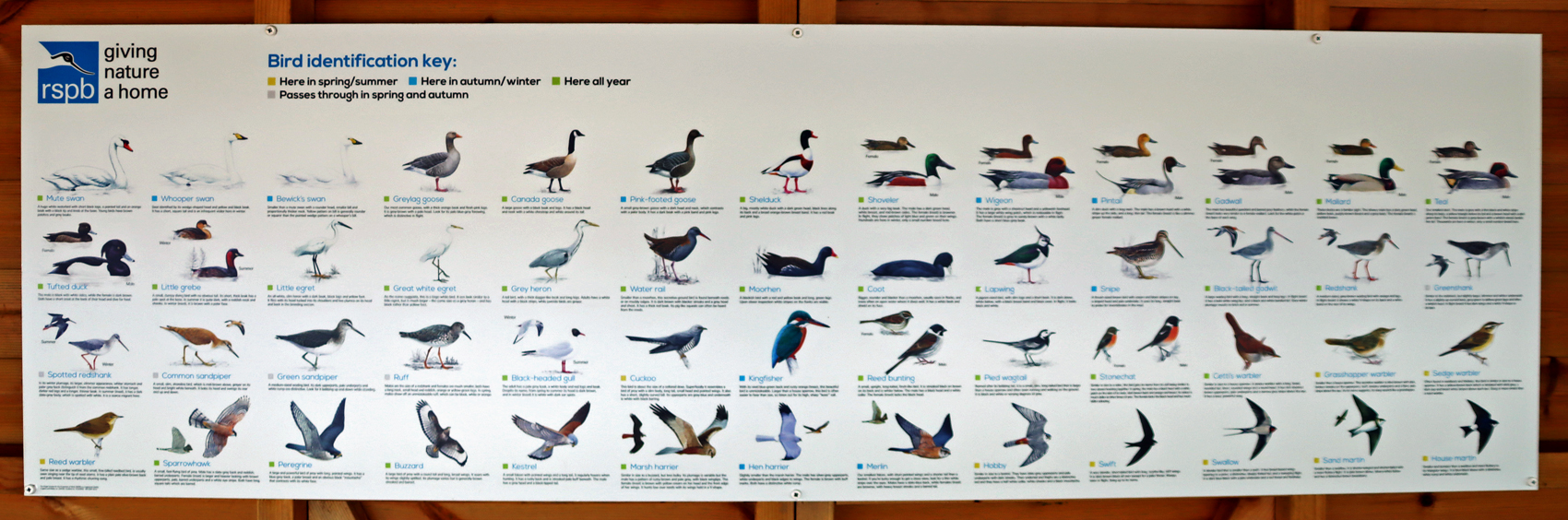

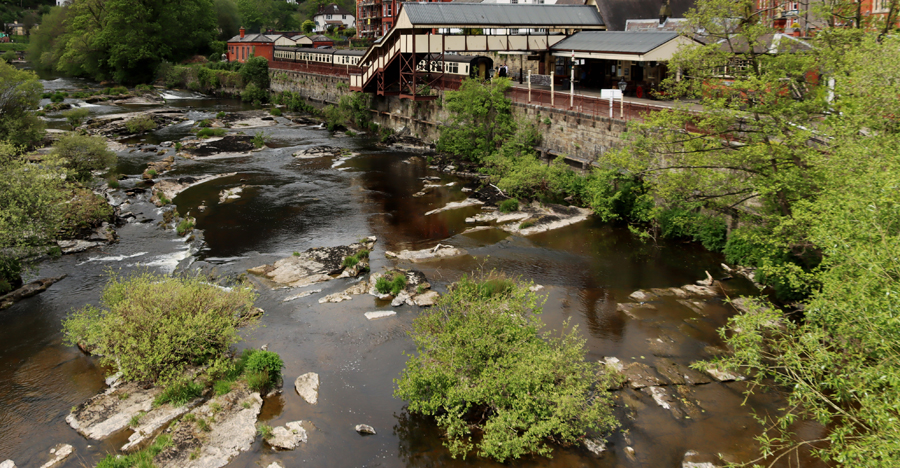

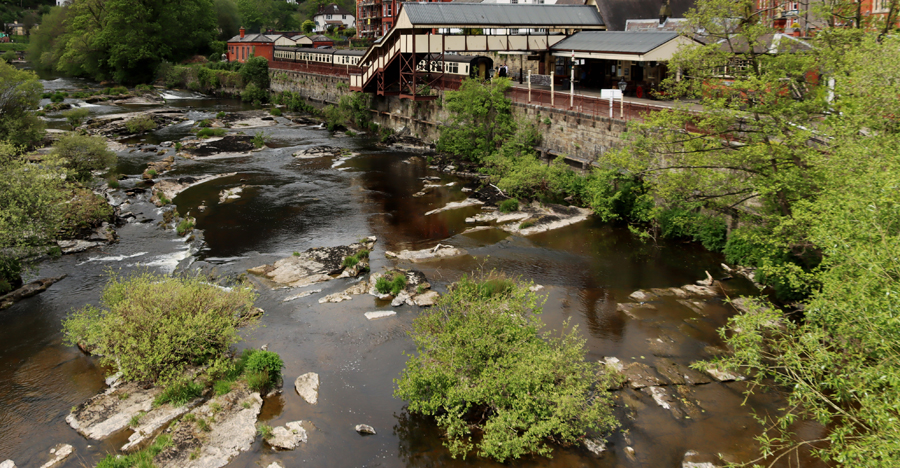

Beneath your feet the rock formations are dark grey Silurian shales and silstones, which were laid down as deep sea sediments and then subjected to metamorphic processes. These are the same rocks that you see in the Dee river bed from the Llangollen bridge, with the rapids flowing over them. The stone quarried from the ditches of this Silurian hillside were used to build the castle, and are uncleaved, around 30-40cm thick.

Above this layer in Llangollen is the heavily layered Carboniferous limestone escarpment that so dramatically forms a backdrop to Llangollen and Dinas Brân, laid down when the sea was warm and shallow. The Devonian, which theoretically should have sat between these two geological periods, is missing, presumably because it was not under water in this area at that time, and did not form the rich, deep layers usually laid down in marine contexts.

The solid geology of Clwyd showing rock types. Jenkins 1991, p.14

Geomorphologically, the Vale of Llangollen is a typical U-shaped valley carved by the advancing ice and associated debris of the Welsh Ice Sheet as it advanced east. The river Dee wends its way through this flat base, and former river beds are visible in the landscape, the former routes of the river blocked by the ice sheet, forcing water to find a new passage.

The plant life that has settled into place on this isolated outpost is typical species that are capable of surviving on highly exposed rock with very little topsoil. Drought-resistant annuals like foxgloves and swathes of rock-hugging perennial succulents like sedum anglicum are dominant at this time of year.

xxx

Visiting

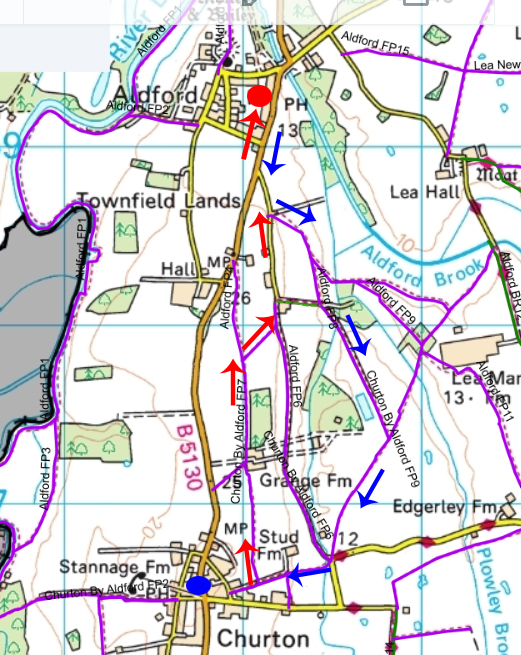

Map of the footpaths to Dinas Brân Castle (Kightly 2003, Denbighshire County Council)

The castle is on the open hilltop and is free of charge to access. There are no facilities at all. You will need to take water and any snacks with you, although there are plenty of facilities down in Llangollen itself.

There are two main approaches to the castle for walkers arriving by car from the east. One is a longer walk from the valley bottom, and the other is a much shorter but slightly steeper walk from the other side, approached along the narrow road now marked on the map as the Offa’s Dyke Path (even though Offa’s Dyke does not actually follow this exact path). A map taken from the bilingual booklet Castell Dinas Brân Llangollen (in their Enjoy Medieval Denbighsire series) shows two alternative routes, with variations.

The easiest place to park if you are heading up from the valley is the International Eisteddfod Pavilion (marked as the Royal International Pavilion on the map), which offers a really lovely walk along the canal to arrive at the canal bridge where you cross to begin the walk. The second approach is much shorter and takes you from the Offa’s Dyke Path, a single-track road that follows the line of the hill, and has spectacular views; there is no official parking here, although there is space to pull over and park for about 4-5 cars (being careful to leave passing spaces) and this gets full very quickly on fine days.

Both routes require sensible footwear, whatever the weather. I was wearing some excellent lightweight hiking trainers with heavy tread, perfect for a hot day, but in damper seasons I would go for hiking boots. Although the path starts off metalled in Llangollen itself, mainly because it is one access point to the local school, it becomes much more uneven underfoot as the path goes on, with patches of coarse bedrock and scatterings of loose scree.

The Eisteddfod Pavilion is on the A539 on the way out of Llangollen towards Valle Crucis and the Horseshoe Pass. The car park is big, with a pay and display system. From here, go up out of the car park towards the canal bridge, and go down on to the towpath to the left of the bridge, turning to the right under the bridge to head east in the direction of Llangollen. This is a lovely stretch of canal, passing the marina on your left.

The Eisteddfod Pavilion is on the A539 on the way out of Llangollen towards Valle Crucis and the Horseshoe Pass. The car park is big, with a pay and display system. From here, go up out of the car park towards the canal bridge, and go down on to the towpath to the left of the bridge, turning to the right under the bridge to head east in the direction of Llangollen. This is a lovely stretch of canal, passing the marina on your left.

When you reach the next canal bridge, with a cafe on the right, walk up on to the bridge. Directly in front of you, heading straight up a short flight of stairs, is the public footpath.

From here on it is easy to find your way. Just keep going straight up. You first pass the school on the left, and a field on the right, with a gate at the top of this first stretch. Go through the gate, cross the lane, and keep going up the other side.

You will pass various attractive buildings along the way, the largest of which is the Grade II listed Dinbren Hall, built with conviction but without a great deal of imagination in a very lovely location in 1793.

Soon you will reach another gate. This has signage on the other side of it warning to inform you that you have now arrived at the foot of the hill, and to keep dogs on a lead (there are sheep all the way along this walk).

It is less even underfoot from here, with a very short uneven patch, but you will find that just over the other side the path opens out onto the hillside, with a clear view of the path ahead.

A very short uneven section of path, but it evens out just on the other side

Beyond this, along the steepest part of the route, the ziz-zag path marked on the map is beautifully maintained at the time of writing, with occasional stretches provided with a hand rail and long shallow steps where required.

This brings you out at the the west end of the castle, where the Victorian camera obscura and teashop used to be located. If you are approaching from the other side, via the Offa’s Dyke Path, you will find a similar zig-zag arrangement to provide a less strenuous way up the hill than heading straight up the side.

Eastern approach to the castle

You can easily turn this into a circular walk from the Eisteddfod pavilion. For the quickest of the two easiest routes, come down from the castle onto the lane under the limestone escarpment and head downhill along the Wern Road, which takes you back to the canal bridge. For a longer but really attractive route, continue along Offa’s Dyke Path, past Wern Road, which eventually heads downhill and comes out at the Sun Trevor on the A542; cross the road, cross the canal bridge, turn right and walk back along the towpath into Llangollen. Although this is a much longer way back, it is all metalled lane and nicely maintained towpath, so is very easy underfoot.

Sources

Ordnance Survey Explorer no.256: Wrexham/Wrecsam and Llangollen. Particularly useful if you want to make this into a circular walk, or to visit other local sites like the Horseshoe Falls and Valle Crucis Cistercian abbey.

If you are particularly interested in medieval architecture in the Denbighshire area, do download their bi-lingual PDF booklet Enjoy Medieval Denbighshire.

Map showing sites featured in the “Enjoy Medieval Denbighshire” PDF

Books and papers

Berry, D. 2016 (4th edition). Walks around Llangollen and the Dee Valley. Kittiwake Books

Davies, John 2007 (3rd edition). A History of Wales. Penguin.

Davis, Paul R. 2021. Towers of Defiance. The Castles and Fortifications of the Princes of Wales. Y Lolfa

Kightly, Charles 2003. Castell Dinas Brân Llangollen. Denbighshire County Council (bilingual booklet with excellent illustrations, artist reconstructions, photographs and information)

Jenkins, David A. 1991. The Environment: Past and Present. In (eds.) John Manley, Stephen Grenter and Fiona Gale. The Archaeology of Clwyd. Clwyd Archaeology Service, p.13-25

Jones, N. W., 2020. Castell Dinas Brân, Llangollen, Denbighshire: Condition Survey. Unpublished report. CPAT Report No. 1739

https://coflein.gov.uk/media/366/634/cpatp_144_001.pdf

Roserveare, M. J., 2017. Castell Dinas Bran, Llangollen, Denbighshire: geophysical survey

report. TigerGeo Project DBL161.

Tregellas, Walter 1864. Castell Dinas Bran Near Llangollen, Denbighshire. The Archaeological Journal, 21, p.114–120

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1132-1/dissemination/pdf/021/021_114_120.pdf

Turvey, Roger 2002. The Welsh Princes. The Native Rules of Wales 1063-1283. Pearson Education

Venning, Timothy 2012. The Kings and Queens of Wales. Amberley

Websites

Coflein

Castell Dinas Bran

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/307064/

Clwydian Range and Dee Valley

Dinas Brân

www.clwydianrangeanddeevalleyaonb.org.uk/projects/dinas-bran/

CPAT

Historic Landscape Characterization: The Making of the Vale of Llangollen and Eglwyseg Historic Environment

https://heneb.org.uk/archive/cpat/projects/longer/histland/llangoll/vlenvi.htm

Heneb

Castell Dinas Brân, Llangollen

https://heneb.org.uk/cy/project/castell-dinas-bran-llangollen/

Dinas Brân, Llangollen Community, Denbighshire (HLCA 1150)

https://heneb.org.uk/hcla/vale-of-llangollen-and-eglwyseg/dinas-bran-llangollen-community-denbighshirehlca-1150/

Recclesia

Castell Dinas Bran

https://recclesia.com/our-work/castell-dinas-bran

Scottish Geology Trust GeoGuide

Dinas Brân

https://geoguide.scottishgeologytrust.org/p/gcr/gcr19/gcr19_dinasbran

You can explore the castle from afar via this Sketchfab 3D model by Mark Walters.

A video showing the two main stages of occupation of the Dinas Bran hill, on the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley website, beginning with the hillfort and moving on to the medieval castle.

xxx

To start the walk walk from the car park to the canal, just a few steps away, and turn right, heading south. During the first couple of minutes the canal passes homes on the other side of the canal. There is a section where it passes a golf course on the opposite side, but it is soon a very rural route with open fields flanking the canal. Long Lane suddenly appears to the right as you walk south, the quiet stretch of road running parallel to the canal. Shortly after this, official moorings begin on the other side of the canal, with a line of narrow boats and small cruising boats as far as the eye could see. I stopped at Golden Nook Bridge and turned back, but the moorings presumably continue all the way to Tattenhall Marina.

To start the walk walk from the car park to the canal, just a few steps away, and turn right, heading south. During the first couple of minutes the canal passes homes on the other side of the canal. There is a section where it passes a golf course on the opposite side, but it is soon a very rural route with open fields flanking the canal. Long Lane suddenly appears to the right as you walk south, the quiet stretch of road running parallel to the canal. Shortly after this, official moorings begin on the other side of the canal, with a line of narrow boats and small cruising boats as far as the eye could see. I stopped at Golden Nook Bridge and turned back, but the moorings presumably continue all the way to Tattenhall Marina.