The Williamson Art Gallery in Birkenhead. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A traditional art gallery and museum in Birkenhead seems unexpected, but when the Williamson Art Gallery and Museum opened in 1928, Birkenhead had not yet fallen into the decline that eventually followed the 19th century economic industrial expansion created by the ship building industry. The gallery was funded by philanthropists John Williamson and his son Patrick Williamson. John Williamson was a shop owner and merchant who became a director of Cunard when it formed as a public company, serving until 1902. He was also on the board of Standard Marine Insurance and served on the Merseyside Docks and Harbours Board. His son does not appear to have had a career but co-operated with his father on philanthropic activities. The museum’s design is a simple brick-built square, with a prominent facade that references Classical features. The steps dominate in the above photo, but there is a ramp at the side for easy access. The gallery is all on one floor, so this too provides ease of access.

I visited with my friend Julian in December 2025. We drove guided by the SatNav, which was needed as the Williamson is surrounded by something of a residential rabbit warren (with some very attractive Victorian terracing if you keep an eye open). There is a free car park on Mather Road that had plenty of spaces. Full visiting details, both for drivers and those using public transport, are at https://williamsonartgallery.org/visit/. Apologies for the quality of the photos inside the gallery, taken on my smartphone. As always in galleries there is reflection from protective glass in many of the photos, but hopefully they will give a good idea of the exhibits.

The gallery is all on a single storey, arranged in a square of linked galleries around what is now the café (with artworks on the walls) and a sculpture garden. A pre-visit inspection of the site plan indicated that around half of it is used for permanent collections, whilst the rest is home to temporary exhibitions. The twin focal points are, in the main, 19th and early 20th century and modern, including furnishings, ceramics, paintings, textiles, sculptures and, on this occasion, a modern video installation. The inclusion of temporary exhibitions is probably very attractive to local people who have reason to visit on repeat occasions.

The first of the galleries that we visited was a temporary exhibition showing the results of the 31st exhibition of the annual Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize (2025). The exhibition “celebrates the role and value of drawing with creative practice and provides a forum to test, evaluate and share current drawing practice.” There is a wide variety of styles and subjects along a continuum from representational to abstract. The skill on display was impressive, and some of the pieces were visually stunning. The mainly monochrome entries drew attention to different combinations of line and texture, with the analytical, humorous and occasionally alarming all demonstrating the versatility of the medium.

The first of the galleries that we visited was a temporary exhibition showing the results of the 31st exhibition of the annual Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize (2025). The exhibition “celebrates the role and value of drawing with creative practice and provides a forum to test, evaluate and share current drawing practice.” There is a wide variety of styles and subjects along a continuum from representational to abstract. The skill on display was impressive, and some of the pieces were visually stunning. The mainly monochrome entries drew attention to different combinations of line and texture, with the analytical, humorous and occasionally alarming all demonstrating the versatility of the medium.

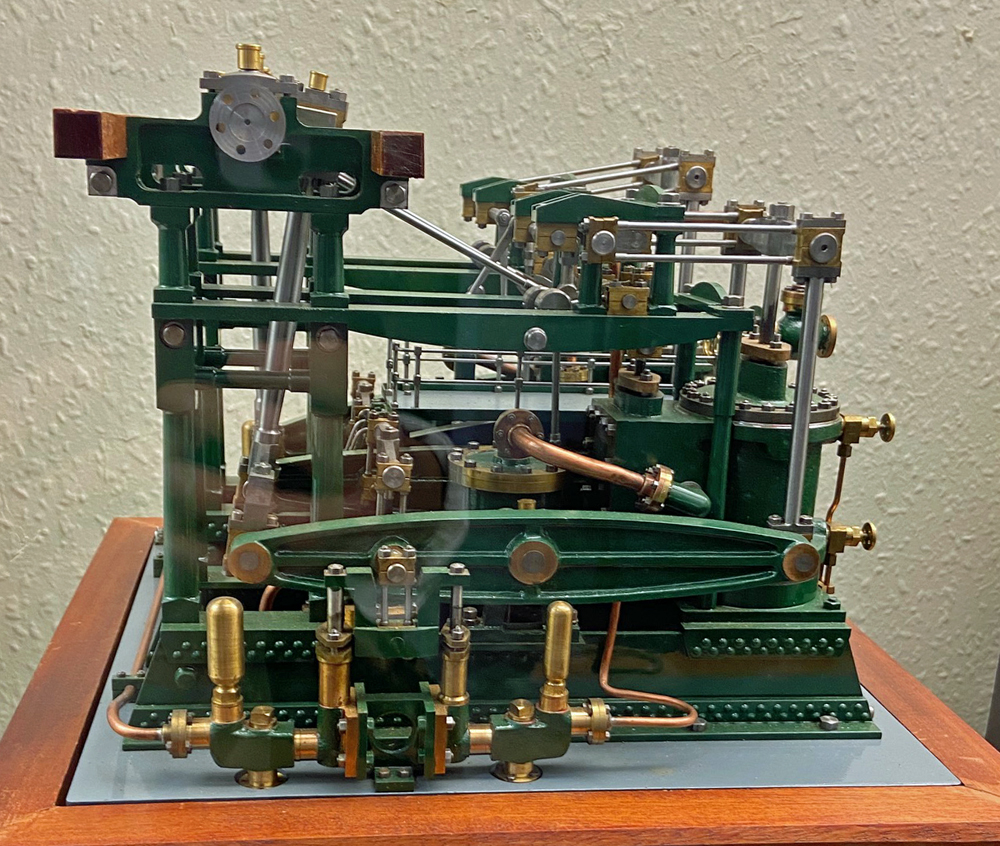

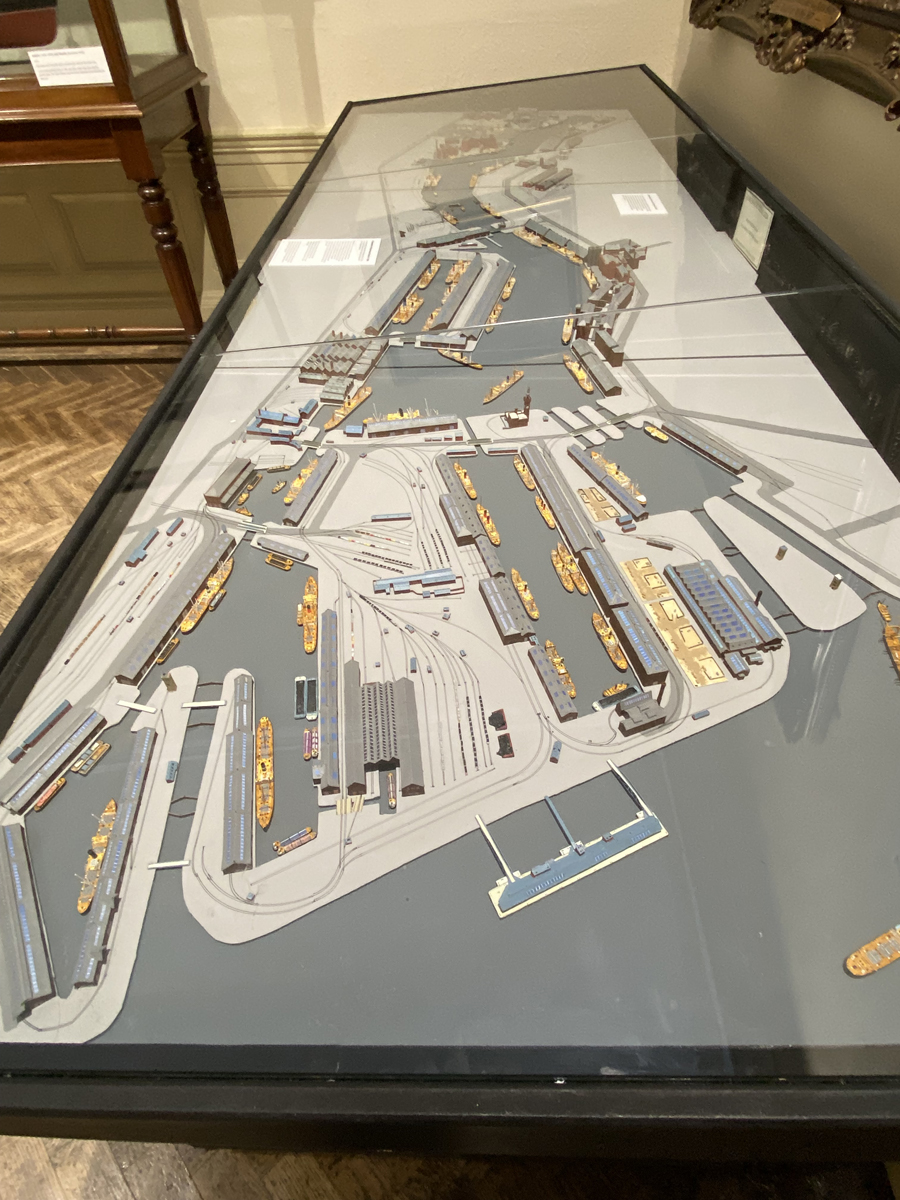

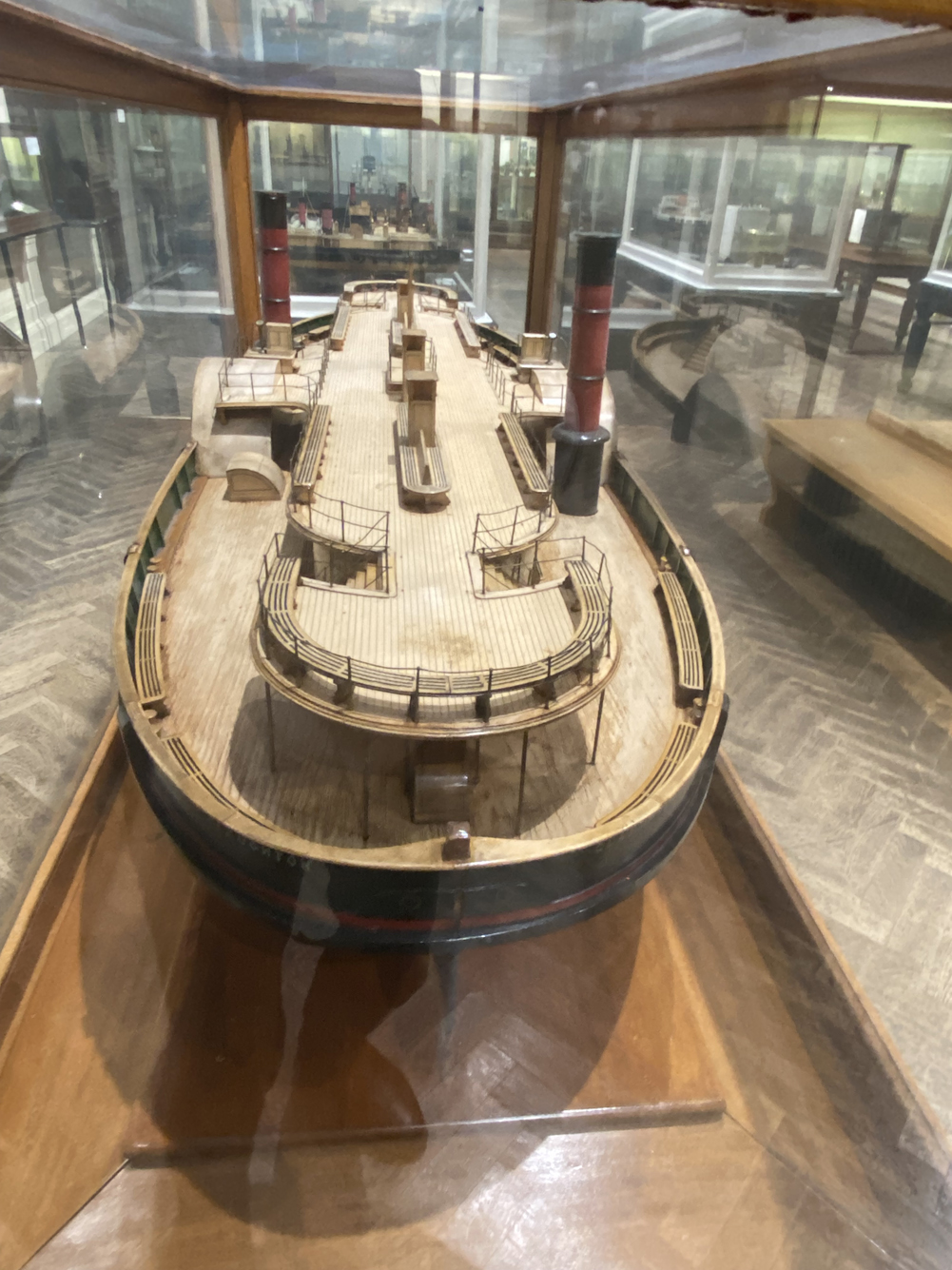

For me, the highlight of the permanent collection was the Maritime room, which is filled with models of ships built locally, as well as the actual fittings from some of the ships depicted by the models. A model of the Birkenhead Docks is really evocative of the size and scale of the operation (shown at the end of the post). The models of Mersey ferries are truly splendid, including a deliciously curvaceous Art Deco-flavoured example. It was a genuine delight to see a model of the S.S. Mauretania, as well as objects that furnished her, because my grandad was quartermaster and helmsman on the ship. It turns out that my friend Julian’s grandfather was a marine engineer, so there was a particular sense of connection for both of us with these beautifully crafted insights into Birkenhead and Mersey shipping. The whole room is redolent of local maritime history. Given that the Liverpool Maritime Museum is disappointingly closed indefinitely whilst funding is being sought, this gallery in the Williamson offers the best available local insight into Mersey shipbuilding and shipping.

For me, the highlight of the permanent collection was the Maritime room, which is filled with models of ships built locally, as well as the actual fittings from some of the ships depicted by the models. A model of the Birkenhead Docks is really evocative of the size and scale of the operation (shown at the end of the post). The models of Mersey ferries are truly splendid, including a deliciously curvaceous Art Deco-flavoured example. It was a genuine delight to see a model of the S.S. Mauretania, as well as objects that furnished her, because my grandad was quartermaster and helmsman on the ship. It turns out that my friend Julian’s grandfather was a marine engineer, so there was a particular sense of connection for both of us with these beautifully crafted insights into Birkenhead and Mersey shipping. The whole room is redolent of local maritime history. Given that the Liverpool Maritime Museum is disappointingly closed indefinitely whilst funding is being sought, this gallery in the Williamson offers the best available local insight into Mersey shipbuilding and shipping.

The C.S.S. Alabama, built Camell Laird’s shipyard, in theoretical violation of official Government neutrality in the American Civil War, is represented at the Williamson by both an oil painting and a model (the latter shown at the very end of this post).

Piece of furniture, a sideboard, from Arrowe park. None of the Arrowe Park furniture can be ascribed to a particular carver or workshop. Diana is at centre, possibly an earlier French panel. The cupid-like boys flanking her represent food and drink.

Entirely in step with this growth of maritime industry and the rise of commerce, was Arrowe Hall. The name is now associated with as a hospital, it was originally built in 1935 for John Ralph Nicholson Shaw, who inherited Arrowe Park from his uncle John Shaw, Liverpool Mayor and slave trader. A small gallery is devoted to reconstructing one of the Arrowe Hall rooms, with some truly astonishing, beautifully crafted, enormous and aesthetically rather appalling pieces of furniture and ornamentation, a mish-mash of medieval, Tudor and Jacobean styles executed with enthusiastic Victorian panache. The information board says that most of the pieces of furniture date to the 1880s, but were carved with earlier dates: “This deceit, and staining the oak very dark, was meant to give the owner a heritage and respectability that they didn’t really have.” The detail in the fireplace overmantel below shows considerable skill imitating earlier Renaissance style friezes. At the time of writing, the house is now a home for adults with learning difficulties.

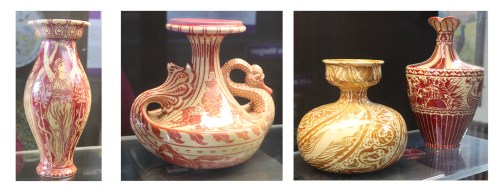

Similarly, the Della Robbia Pottery room is bound to split aesthetic opinion. Della Robbia Pottery, taking the name from Luca Della Robbia (1400-1481), and on whose style it is loosely based, was a remarkably successful Birkenhead enterprise for a short period of time between 1894 and 1906. It was established by Harold Rathbone (1858-1929), who worked with professional designers but also hired young people locally who he trained up. It is lavish, ornate, brightly coloured, glossy, often with multiple textures and sculptural components. Rathbone strained at the Slade School of Art and became a pupil of Ford Madox Brown, and the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites is clear in many of his pieces. Many of the themes of pieces produced by the pottery feature angels, cupids and mythological figures, as well as elaborate and complex patterns.

sdsfds

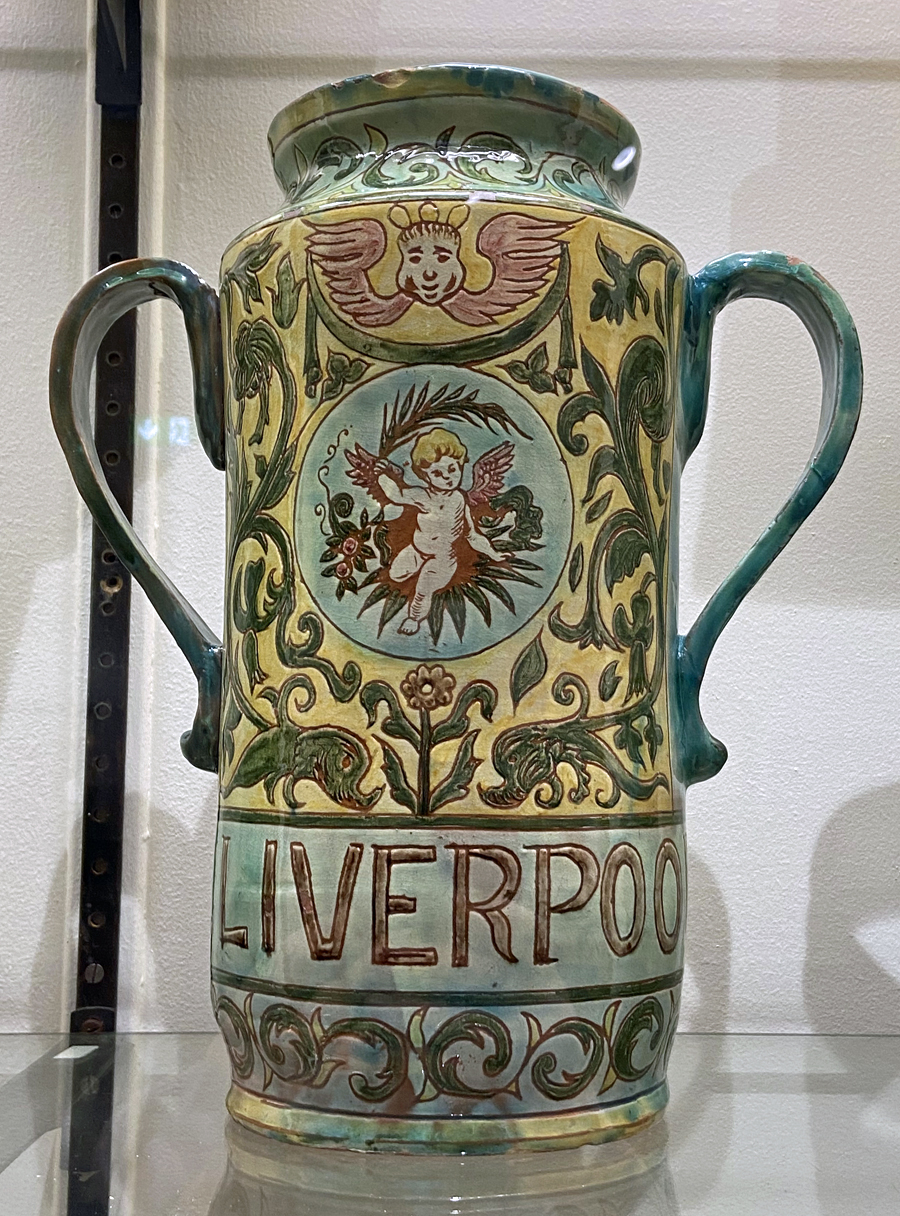

Another small room focuses on ceramics that were either made and used in Merseyside or were imports, brought back to the Mersey docks from the far east to meet the demand of local consumers. Chinese ceramicists cottoned on very quickly to the types of decorative themes that were popular in the west, and produced specific types of design, including specific types of shape, for the European market. The mix is diverse, but there are one or two pieces that directly reference the maritime. The influence of Chinese ceramics is very clear, made either locally or imported, in some of the examples, but there are more localized themes as well. There were seven different sites in Liverpool that were making porcelain, all operating between the mid and late 1700s. Unfortunately, none of the factories used manufacturing marks so it is difficult to determine which factory produced which pieces.

Another small room focuses on ceramics that were either made and used in Merseyside or were imports, brought back to the Mersey docks from the far east to meet the demand of local consumers. Chinese ceramicists cottoned on very quickly to the types of decorative themes that were popular in the west, and produced specific types of design, including specific types of shape, for the European market. The mix is diverse, but there are one or two pieces that directly reference the maritime. The influence of Chinese ceramics is very clear, made either locally or imported, in some of the examples, but there are more localized themes as well. There were seven different sites in Liverpool that were making porcelain, all operating between the mid and late 1700s. Unfortunately, none of the factories used manufacturing marks so it is difficult to determine which factory produced which pieces.

xxx

Paintings by Ukrainian children, produced since the start of the war, from the Sunflower Dreams Project were on display during our visit, alongside paintings by Maria Prymachenko. The exhibitions produced by Sunflower Dreams are displayed in Britain, North America and Europe. Although the Sunflower Dreams Project exhibition at the Williamson ended in December 2025, at the time of writing you can still find full details about the project, with samples of the paintings produced by this admirable initiative on https://sunflowerdreamsproject.org/. Maria Prymachenko (1909-1977) specialized in Ukrainian folklore and was awarded a gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1937 for her wonderful, brightly imagined paintings. She was largely forgotten after the Second World War, but there was a resurgence of interest in her work in the 1960s and she is now featured in a number of international museums.

The painting collection on display during our visit strongly featured the landscape and seascape artist Philip Wilson Steer (1860-1942), who was born in Birkenhead, although grew up elsewhere. He had spent time in Paris and was strongly influenced by the Impressionists and other contemporary artists. In his A Girl at Her Toilet of 1992-3, the theme of women engaging in personal behind-the-doors activities, so popular with Impressionist painters, is given a more dramatic overlay of contrasting colours, clearly inspired by Éduard Manet. the label says that the “intimate or even voyeuristic” tone of his painting was “ridiculed by English critics partly for the perceived indecency of his choices of subject matter.” By complete contrast, his Seascape off Walmer of 1930 was painted as he began to lose his eyesight, retaining only peripheral vision by 1935 when he moved almost completely over to watercolour. The entire composition is made up of thin washes of pale blue that create a delicate, almost abstract seascape with a single small boat in the distance, creating the only sense of depth.

There were a set of paintings by Albert Richards (1919-1945), who has the sad distinction of being the youngest official War Artist to be killed in action in the Second World War, just two months before VE Day when the jeep in which he was travelling ran over a landmine. He was born in Liverpool but moved to Wallasey when young, training at the Wallasey School of Art.

Albert Richards – Della, c.1938. Painted when the artist was attending Wallasey School of Art. Gouache on paper.

Many of the other paintings on display by other artists from the period, both watercolours and oils, are obviously influenced by more accomplished Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, but are interesting as examples of how local artists were influenced by the latest trends.

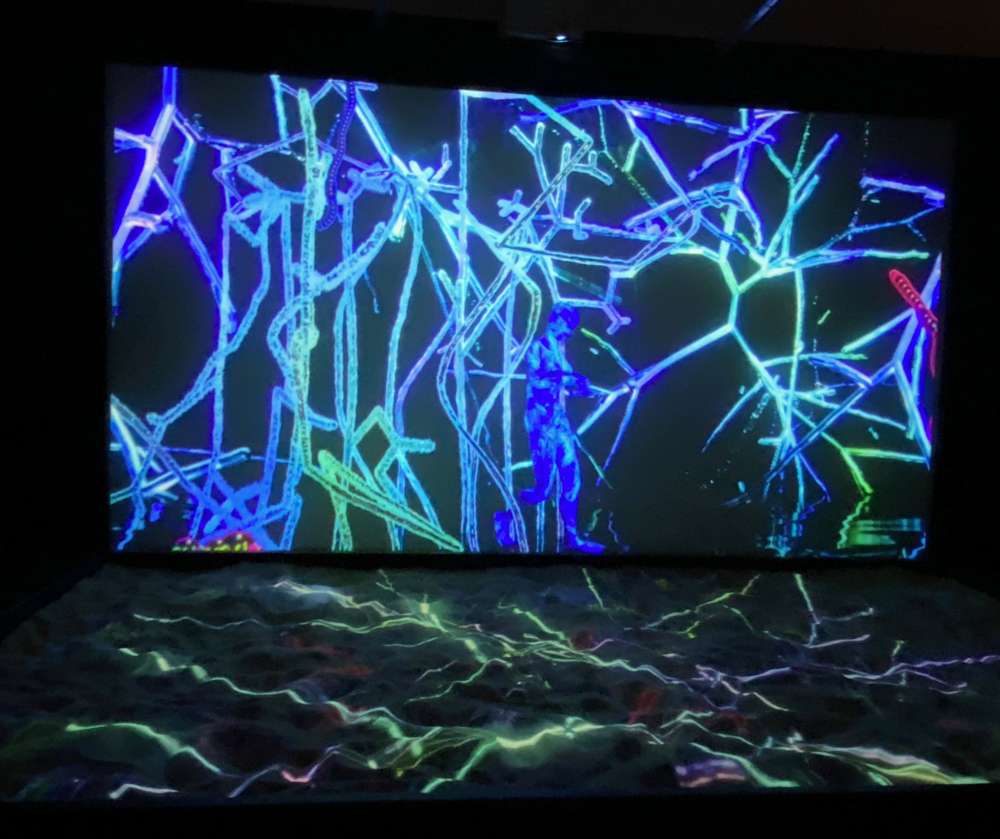

Temporary installation – Di Mainstone’s “Subterranean Elevator,” which shows continually throughout the day. On until the end of January.

Because at least half of the Williamson is dedicated to temporary collections, a lot of the paintings are in storage. None of the better known examples from the permanent collection were on display when we visited, including the glorious watercolour of Brunel’s S.S. Great Eastern beached on the Mersey for repair work by William Gawin Herdman in 1863 and the Joseph Mallord William Turner’s dramatic watercolour Vesuvius Angry, both of which I was really hoping to see. I checked with the information desk after our visit, but the consensus was that they were both in storage. The comprehensive and very nicely presented online catalogue shows what the Williamson holds, but it does not indicate what is or is not on display.

xxx

Liverpool and Birkenhead, attributed to Charles Eyes 1767, showing Birkenhead Manor and Priory. This photo is taken from the Williamson’s online catalogue at https://williamsonartgallery.org/item/1580053/

The café, with more paintings on the walls was producing some very good-looking meals and bakes, and the coffee was excellent. One of the paintings was a very evocative one of pre-industrial Birkenhead showing the manor and the ruined priory, the sister paining of one in Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery. I couldn’t get to it without trampling some diners underfoot, so the picture to the right is taken from the online catalogue. There is also a small shop area with books against one wall, and a few postcards. The sculpture garden, which can be reached from the café, looks interesting, but it was pouring with rain, so we abstained.

The Williamson represents Birkenhead and the Mersey, both past and present. The policy of the gallery is to mix its core collection of 19th and early 20th century art and decorative arts, with temporary exhibitions, often featuring contemporary works, and it is well worth keeping an eye on what their temporary exhibitions offer, either by checking the Williamson website or signing up to the email newsletter.

Frozen Fabric: Spectrum 1983 by Anna Sutton OBE (b.1935), British textile artist and designer. In this example she transforms a simple weave into a sculptural object, “merging textile traditions with minimalist abstraction.”

17th century Japanese temple bell, in the Arrowe Hall room. If it ever goes missing, you will know where to look!