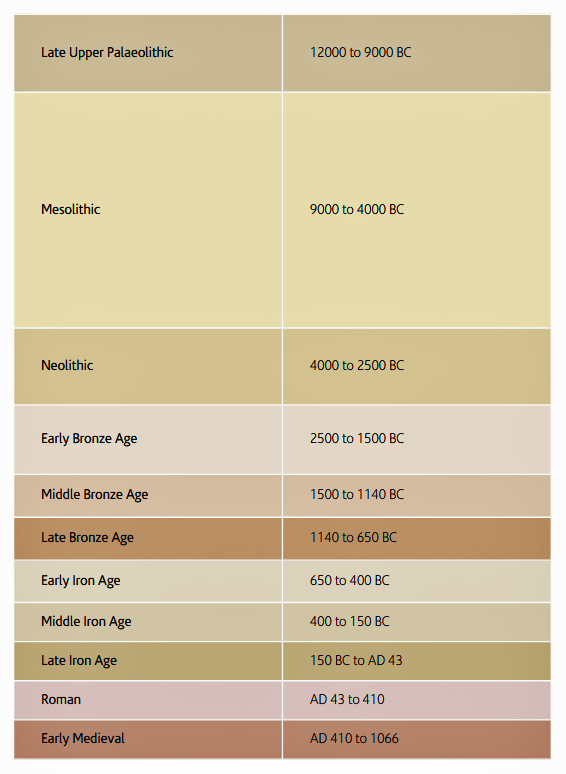

Introduction

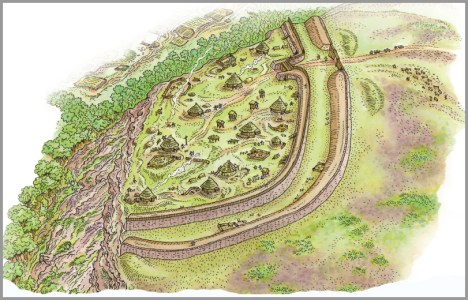

Artist’s imaginative interpretation of how Maiden Castle may have looked, based on information from both the site itself as well as from other excavated hillforts. As no excavations have taken place in the interior beyond the entrance area, the roundhouses and accompanying square structures are largely speculative. Produced by the Habitats and Hillforts Project 2008-2012. Source: Sandstone Ridge Trust

Further to last week’s walk on Bickerton Hill, Maiden Castle sits on the route of the Sandstone Trail, on the northeast edge of Bickerton Hill (once known as Birds Hill), which is one of the Triassic red sandstone outcrops that make up the mid-Cheshire Sandstone Ridge. It is the southernmost of six hillforts along the ridge (see topographical map below). A visit to the hillfort makes for a great walk with lovely views over the Cheshire Plain.

Traditionally hillforts were associated with the Iron Age, and in general the early and mid Iron Age periods, but modern excavations have revealed that many had their origins in the Late Bronze Age, that not all of them were contemporary, and some were re-used in the post-Roman period. Some have a long sequence of occupation and abandonment, and many may have performed different functions, both in terms of geographical distinctions and even within localized areas.

All hillforts make use of the natural topography in order to provide their enclosures with good defensive potential, including good views over the landscape. Many strategic locations are also shared, either actually or conceptually, by medieval castles.

Some hillforts surround the very top of a hilltop, such as Beeston Castle on the Sandstone Ridge to the north (a location used by Ranulph III, 6th Earl of Chester, for his medieval castle), but others like Maiden Castle are located to take advantage of a natural drop on one or more sides to provide some of the defences. These are usually referred to as promontory hillforts, and Maiden Castle is a good example. The built defences form a dog-leg curve that meets on either side of a slight projection over the steep drop of the Sandstone Ridge where it plunges down to the Cheshire Plain. As well as reducing the amount of work required to provide defences for the site, promontory forts could be just as visible as those that circled hilltops. In the case of Maiden Castle, the height of the site (c. 698ft/212m AOD) and the views from its banks at the east of the hillfort also provide good views to the east. Although it is at the highest point of Bickerton Hill, Maiden Castle only occupies a part of the high ground, presumably its size, smaller than most of its neighbours, sufficient for its needs.

Google Map of Bickerton Hill and Maiden Castle. The purple marker shows the centre of the hillfort. The ditches between banks are visible as the darker arcing lines

Maiden Castle, in common with other hillforts, had no obvious source of water, and could not therefore withstand a prolonged siege, assuming that it had a defensive role. In addition, any livestock herded on the outcrop would need to be returned to a water source. Springs were available along other parts of the sandstone trail, many of which are now dry, and some wells mark access to water today, including Droppingstone Well at Raw Head, under 3km away, and the medieval well at Beeston Castle (now dry), but there were no rivers or streams nearby. The nearest is Bickley Brook, around 2km to the east. However, it is likely that there was a lot of standing water and ponds as well as a diversity of small and possibly seasonal wetland habitats that supported different types of wildlife, with a strong avian component. It is interesting that of all the hillforts on the Sandstone Ridge, only Maiden Castle did not neighbour a river or well-sized mere, nor a well-fed stream or small mere.

Topographical map of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, showing Maiden Castle at the south end. Source: Garner et al 2012

The question of a water supply draws attention to the fact that the exact role of hillforts in this part of the country is not fully understood. The often massive ditches and banks, the latter supporting additional structures such as palisades, were quite clearly intended to keep one set of people (and their possessions) in, and presumably another set of people out. Specialized entrance designs reinforce this idea of controlled and limited access. At some hillforts slingshot stones, usually interpreted as evidence of warfare, have been found including at the Sandstone Ridge hillforts Woodhouse and Eddibsury, made of rounded sandstone pebbles. However, whether warfare is the correct model for the role of Cheshire hillforts is by no means clear. Localized disputes such as cattle and grain raiding might be a more plausible scenario than all-out warfare, with the hillforts perhaps (speculatively) providing places of retreat from farmsteads dotted around the surrounding plains at times of threat. The scale of investment in these structures certainly suggests that whatever their role, they were seen as necessary for local security, and probably for conveying territorial ownership and status as well. An experiment to test inter-visibility between hillforts in northeast Wales and Cheshire, called the Hillfort Glow was undertaken in 2011 by the former Habitats and Hillforts. Sadly, the Habitats and Hillforts website is no longer available, but the experiment was reported on the BBC News website. Ten Iron Age hillfort sites were included (on the Clwydian Range, Halkyn Mountain, the mid-Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, and at Burton Point on the Wirral). It suggests that if allied groups wanted to communicate a threat to neighbours, they could do so quite easily, with Burton Point on the Wirral, for example, visible as far always as Maiden Castle 25km (15.5 miles) away, as well as nearer sites on the Clwydian Range.

Maiden Castle defences as they look today, at the far south of the hillfort, seen from near the edge of the ridge, with the dark shadow marking the ditch, facing roughly to the east.

If you visit Maiden Castle in person (see Visiting details at the end for how best to locate it), you will find that the enclosure ditch between the two lines of rampart is clearly visible, although considerably less impressive than it would have been in the Iron Age, and you can walk along it very easily. The photograph here shows it in late autumn afternoon light, with the ditch clearly marked by the line of shadow.

Excavations and surveys

Varley 1940, Maiden Castle schematic plans, showing Varley’s illustrations of the defences, the entrance and the construction of the banks, showing the stone facings, figs.11 and 12, p.70-71

The Maiden Castle hillfort was first excavated by William Varley, (a geography lecturer at the University of Liverpool) and J.P. Droop (who was also involved in the Chester Amphitheatre excavations) over two seasons between 1934 and 1935, published promptly by Varley over two years in 1935 and 1936, after which Varley moved on to Eddisbury Hillfort near Frodsham. In 1940, as the first of a new series of history books, The Handbooks to the History of Cheshire, he co-authored Prehistoric Cheshire with John Jackson, with illustrations, photographs, fold-out maps and a bibliography organized by archaeological period.

Varley’s published excavations at Maiden Castle were carried out to a very high standard. As with the later book, he included plans and photographs of the entire site with particular emphasis on his excavations, which were focused on the northern end and included the entrance, and both outer and inner ramparts.

Maiden Castle, showing how the inner bank was turned inwards to form a corridor entrance. Source: Varley 1936

The excavations were very informative, confirming that there were two ramparts separated by a ditch and suggesting an additional ditch surrounding the entire defences. A possible palisade trench under the outer of the two Iron Age ramparts is the only indication that he found of a possible pre-Iron Age line of defences. The inner rampart was built using timber and sand, and was faced with stone on both sides. The outer rampart was formed of sand and rubble, with the outer side also faced with stone. The inner rampart enclosed an area of around 0.7ha, with an entrance at the northeast formed by turning both sides of part of the inner rampart inwards, to form a corridor c.17m long and 0.8m wide. A pair of postholes set within the entrance area may have been gate posts. The entrance in the outer rampart was a simple gap, lined up with the inner rampart entrance. Varley believed that so-called guard chambers (by then identified at some other hillforts) once flanked the entrance, marked by archaeological surfaces, one of which produced a piece of Iron Age pottery. However, no structural remains survived to substantiate this interpretation. The ditch between the two ramparts is clearly visible today, particularly at the south end, but Varley also identified another ditch on the far side of the outer rampart, which appears to have been confirmed by the LiDAR survey carried out in 2010. Varley’s plans and photographs have contributed to more recent research and remain a useful resource.

xxx

Although no further excavations were carried out until 1980, a number of topographical surveys were undertaken in an attempt to clarify matters. The 1980 excavation, published by Joan Taylor (University of Liverpool) in 1981, was undertaken in response to damage unintentionally inflicted on part of the ramparts by walkers, which revealed some of the internal burnt wooden construction material. This was an opportunity to re-examine the construction methods and to send some of the charred wood for radiocarbon dating, which produced dates in two clusters, which were later calibrated (a form of correction) by Keith Matthews, then with the Chester Archaeology Service. The results indicated that Varley’s instincts that the inner rampart predated the outer one were correct, producing a set around 860-330 cal.BC for the inner rampart and a set of 380-310 cal.BC on the outer rampart.

LiDAR clearly shows not only the banks and ditches but also the damage inflicted by stone quarrying both within and beyond the hillfort enclosure. Source: Garner 2012, p.50

No further excavations have taken place at the site, but a the Habitats and Hillforts project undertook a number of non-invasive surveys of the site, reported in Garner’s 2016 publication. The results of a LiDAR survey were reported, revealing that considerable damaged from later stone quarrying to the ramparts and the interior, as well as across the rest of the hill. It additionally confirmed that there were trenches from when the army had a training base and firing range at the site in the later 20th century. Finally, geophysical surveys were carried out by Dr Ian Brooks in 2011, again reported in Garner 2016, which included both resistivity and magnetometry surveys, the latter producing signs of three possible roundhouses, one of which made up a full circle, their diameters measuring 6.9m, 7.8m and 9.2m. This is a good indication of the potential of the site for producing further information, even with the probable damage to parts of the archaeological layers from quarrying (marked on the LiDAR image below as irregularly shaped depressions), but not much else can be concluded without excavation.

Possible roundhouses revealed by geophysical survey, shown in red, with irregularly shaped pits produced by later quarrying for stone. Source: Garner 2017, p.58

Summary of the amalgamated data

The structural character of the site

Artist’s impression of how ta simple inturned entrance may have looked, with a palisade on what remains of the ramparts and a walkway over the gateway, with roundhouses just visible in the interior. Source: Sandstone Ridge – Maiden Castle heritage leaflet

The site is defined by an interior sub-rectangular space enclosed on the east by a pair of ramparts, each with an external ditch, and on the west by an angled section of the precipice that once met up with either end of the ramparts, creating a complete defensible boundary. There are good indications that when it was first built there was only one rampart. A stone-faced entrance penetrated the ramparts at the northern end, with a corridor-style inturned section of the inner boundary, with postholes flanking the entrance suggesting that the interior was protected by gates. Although the interior has been badly damaged by quarrying for stone, geophysical investigations have suggested that roundhouses were present within the enclosure. The site had immensely clear views to the west, and good views to the east.

This is quite a small site compared to others nearby. For example, it is around half the size of Helsby hillfort to which it is otherwise similar in appearance. One suggestion is that it is more akin to an enclosed farmstead than a place for community aggregation and defence. Having stone-lined ramparts, the site would have been both visible and impressive, perhaps a statement about social identity and affiliation with the land around the hill. Still, the addition of a second rampart argues that defence was an important aspect of the design.

Chronology

There is only faint evidence of a Late Bronze Age predecessor for the Iron Age hillfort, although this might be expected because Beeston Castle demonstrated clear Late Bronze Age structural features, and Woodhouse, Kelsborrow and Helsby all produced possible evidence of Late Bronze Age construction. The only evidence is a possible palisade slot under the outer of the two Iron Age ramparts. However, the level of disturbance created by stone quarrying in the interior may well have eliminated earlier data. Unfortunately there were no diagnostic artefacts to assist with the question of dating but radiocarbon dates obtained during the excavations during the 1980s suggest that the inner rampart predates the outer rampart, with three radiocarbon dates from the inner rampart spanning 860 to 330 BC whilst those from the outer rampart included one of 380-10 BC.

Economic resources

There are few sites in the immediate area that provide insights into the economic activities in which the local communities were engaged, and what the local land might have supported, both in terms of lowland and upland exploitation of domesticated and wild resources. The soil surrounding the outcrop was generally poorly drained leading to damp, sometimes seasonally waterlogged conditions. That on the outcrop itself was shrubby heathland, good for livestock grazing but not for cultivation.

Beeston Castle as it might have appeared in late prehistory. Source: Sandstone Ridge leaflet

There is no data about livelihood management and farming activity available from Maiden Castle, and it is anyway most likely that economic activity took place in the fields below, although it is possible that a site like Maiden Castle would be used to store edible and other resources.

A good idea of what might have been available to the occupants of all the hillforts on the Sandstone Ridge comes from excavations at Beeston Castle, the next hillfort to the north. Between 1980 and 1985 soil samples were taken during the excavations, focusing on areas most likely to provide information about the use of structures. 60,000 cereal items were recovered. Emmer and spelt wheat dominated. Spelt is more tolerant of poor growing conditions, requires less nitrogen to grow, has better resistance to disease and pests, is more competitive against weeds, more tolerant of damp soil conditions, including waterlogging, and can be used to make bread without yeast. On the other hand, the processing stage is very labour intensive. Emmer wheat is only reasonably tolerant of damp growing conditions, makes a denser bread that is higher in protein, and is a lot easier to process. They can be grown separately or as a mixed crop. Grains of hulled barley were also found at Beeston, but in smaller numbers, possibly due to it being much less tolerant than either emmer or spelt to damp conditions. Oat was found in the samples, although it is not know whether this was a domesticated or wild crop. Wild species in the samples that could have been used as a food source were hazelnuts and fruits of the Rubus genus (blackberry, raspberry and/or damsons) and fruits of the Prunus genus (sloe, cheery, and/or plum) and elder berry.

There is a dearth of lowland sites known in the area. Standing on the top of Maiden Castle’s ramparts and looking to the east and west, with views across both the flat stretches of the western part of the Cheshire Plain and the more undulating topography to the east, it is not difficult to imagine Iron Age farmsteads dotting the landscape in a similar way to modern farms today, either enclosed in a ditch and bank arrangement, or simply unenclosed. Even so, a number of such farmstead settlements are known to the west of the Cheshire Ridge as far as (and including) the Wirral, together with some very rare examples of field systems.

The nearest lowland site is Brook House Farm, Bruen Stapleford, around 11km (c.7 miles) away as the crow flies. Very little animal bone was found, probably due to the acidic soil, but included a pig tooth, a piece of sheep/goat/roe deer-sized animal bone, and a few fragments of cow teeth. The poorly drained damp plain would not have been suitable for sheep, although entirely suitable for cattle and pigs. It is worth bearing in mind that the sort of higher ground represented by Bickerton Hill would have been ideal for allowing sheep to roam and feed off upland grasses and shrubs, representing a rare opportunity in Cheshire, should it have been required, for this type of economic diversification, but they would have required access to water when feeding lambs or if used for milk production. Lowland conditions would also have favoured the herding of livestock, and would have been suitable too for raising pigs and horses.

Just as today, the underlying geology and soils would have placed limits on what could be grown agriculturally on the Cheshire Plain. At Brook House Farm plant remains included bread-type wheat emmer or spelt, and some hulled barley. There was a relatively high proportion of grassland species, suggesting that damp slow-draining grassland may have dominated in the area, which would be more suitable for hay production and livestock grazing than crop cultivation.

The combination of crops and livestock using both lowland and upland areas would have been a good way of diversifying economic output, making the most of the environment, and spreading the risk that subsistence strategies would have faced, even when planning on creating a certain amount of surplus for over-wintering and for trade. It has often been suggested that hillforts may have had multiple roles either simultaneously or consecutively over time, and one of those roles may have been storage of surplus grains, preserved meats, salt and items for trade.

Assuming that those sites to the west of Maiden Castle (and the other west-facing Sandstone Ridge hillforts) had clear lines of visibility to the lowland sites on the Cheshire Plain, and vice versa, it would have been just as straight forward to establish visual communication between the lowland sites and the hillfort, as it was between contemporary hillforts.

Final comments

At the moment, hillforts and lowland settlements during later prehistory are not well understood in the Cheshire area. This is partly because relatively few have been comprehensively excavated, but also because lowland sites are particularly difficult to locate. Where sites are excavated, local conditions are not favourable to the preservation of organic materials, and most of them produce few artefacts.

The relationship between hillforts and lowland settlements is also poorly understood. As more of these small farmsteads are identified and excavated, the picture should eventually become a lot clearer, but a number of sites have been identified to date not by crop marks but by accidental discovery during construction works such as pipe and cable laying and housing developments. It could be a long haul.

In the meantime, sites like Maiden Castle, with their earthworks dating back over 2000 years, are a pleasure to visit and to get to grips with. When there are stunning views into the bargain, there is a lot to love!

Visiting

This is a very enjoyable and popular place to visit, managed by the National Trust, and provided with two car parks, one on each side of the hill. Although not well sign-posted, there is plenty of parking provided by the National Trust. I used the Goldford Lane car park, which is well-sized (copy over from my walk). The hillfort can be incorporated into a circular walk that includes Brown Knowle. The views from the top of the ridge are superb. See full details, including the leaflet that describes the route for the Brown Knowle walk at the end of my previous post about walking on Bickerton Hill, including a What3Words address for the car park.

Information panel at the site about Maiden Castle and the heathland in which it sits. Click to enlarge.

Finding the hillfort is a matter of keeping your eyes open for the information plinth where the footpath opens into in a wide clearing with a bench and terrific views, at the highest point of the hill. It can be seen in the Google satellite photograph above as the scuffed area to the bottom left of the picture. If you take the lower of the two paths from the car park, skirting the bottom of the hillfort, you will see the information board easily, but if you take the upper path along the ridge, it is actually facing away from you downhill and is easy to miss.

Walking the ditch between the ramparts is easy enough, but note that the banks are covered in low shrubs and brambles that make it quite hard going underfoot, as the ground is completely invisible and very densely covered in a tight network of shrubby material. However, the views to the east are impressive from the outer rampart. The same can be said for the interior, which is also covered with dense low shrubs and bracken. The thought of excavating it makes me ache all over!

You can read much more about Maiden Castle and other archaeology, geology and landscape on the Sandstone Ridge in the sources below.

Sources

Books and Papers

Driver, Toby 2013. Architecture Regional Identity and Power in the Iron Age Landscapes of Mid Wales: The Hillforts of North Ceredigion. BAR British Series 583

Ellis, P. (ed.) 1993. Beeston Castle, Cheshire. Excavations by Laurence Keen and Peter Hough, 1968-1985. English Heritage

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1416-1/dissemination/pdf/9781848021358.pdf

Fairburn, N., with D. Bonner, W. J. Carruthers, G.R. Gale, K. J. Matthews, E. Morris and M. Ward 2002. II: Brook House Farm, Bruen Stapleford. Excavation of a First Millennium BC Settlement. Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, new series 77, 2002, p.9–57

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-2910-1/dissemination/pdf/JCAS_ns_077/JCAS_ns_077_008-057.pdf

Garner, D. (and contributors) 2012. Hillforts of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge. Habitats and Hillforts Landscape Partnership Scheme. Cheshire West and Chester Council.

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/lib/file-234636.pdf

Garner D. (and contributors) 2016. Hillforts of the Cheshire Ridge. Investigations undertaken by The Habitats and Hillforts Landscape Partnership Scheme 2009–2012. Archaeopress

Abridged version available online, minus appendices (there is no index in either print or online versions, but you can keyword search the PDF):

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter_Marshall14/publication/313797404_Hillforts_of_the_Cheshire_Ridge_Investigations_undertaken_by_The_Habitats_and_Hillforts_Landscape_Partnership_Scheme_2009-2012/links/58a6860aa6fdcc0e078652a7/Hillforts-of-the-Cheshire-Ridge-Investigations-undertaken-by-The-Habitats-and-Hillforts-Landscape-Partnership-Scheme-2009-2012.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=hzbN0_un1j_np6Me4Z0bWxtROgI9juclGR.5XFzS5iY-1764184426-1.0.1.1-RsTsNKNPcI.Zt7JSR8rdabCJKMfRvmSXkjpGJZHx31c

Some of the unpublished reports commissioned during this project, as well as some of the tables that are too small to read properly in the printed versions are currently available at http://bit.ly/2ghWmze.

Matthews, Keith J. 2002. The Iron Age of Northwest England: A socio-economic model. Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society 76, p.1-51

https://www.academia.edu/900876/The_Iron_Age_of_North_West_England_A_Socio_Economic_Model

Schoenwetter, James 1982. Environmental Archaeology of the Peckforton Hills. (2-page summary). Cheshire Archaeological Bulletin, No.8., p.

Schoenwetter, James 1983. Environmental Archaeology of the Peckforton Hills.

https://core.tdar.org/document/6256/environmental-archaeology-of-the-peckforton-hills

, , and 2025. Fraught with high tragedy: A contextual and chronological reconsideration of the Maiden Castle Iron Age ‘War Cemetery’ (England). Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 44: p.270–295

N.B. – This refers to Maiden Castle in Dorset.

Internet Archive: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ojoa.12324

Taylor, Joan. 1981. Maiden Castle, Bickerton Hill, Interim Report. Cheshire Archaeological Bulletin 7, p.34-6

Varley, William 1935. Maiden Castle, Bickerton: Preliminary Excavations, 1934. University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, vol.22, p.97-110 and plates XV-XXII

Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/annals-of-archaeology-and-anthropology_1935_22_1-2/mode/2up

Varley, William 1936. Further excavations at Maiden Castle, Bickerton 1935. University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, vol.23, p.101-112 and plates XLIII-L

https://dn720408.ca.archive.org/0/items/annals-of-archaeology-and-anthropology_1936_23_3-4/annals-of-archaeology-and-anthropology_1936_23_3-4.pdf

Varley, William 1948. The Hillforts of the Welsh Marches. The Archaeological Journal, vol. 105, p.41 – 66

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1132-1/dissemination/pdf/105/105_041_066.pdf

Varley, William and John Jackson 1940. Prehistoric Cheshire. Cheshire Rural Community Council

Websites

BBC News

North Wales hillfort test of Iron Age communication

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-north-east-wales-11832323

Heritage Gateway

Maiden Castle, Bickerton, Hob Uid: 68844

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=68844&resourceID=19191

Historic England

Maiden Castle promontory fort on Bickerton Hill 700m west of Hill Farm

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1013293?section=official-list-entry

Hillforts. Introductions to Heritage Assets

https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-hillforts/heag206-hillforts/

Natural England

https://nationalcharacterareas.co.uk/

National Character Area 61 – Shropshire, Cheshire and Staffordshire Plain

Key Facts and Data

https://nationalcharacterareas.co.uk/shropshire-cheshire-and-staffordshire-plain/key-facts-data/

Analysis: Landscape Attributes and Opportunities

https://nationalcharacterareas.co.uk/shropshire-cheshire-and-staffordshire-plain/analysis-landscape-attributes-opportunities/

NE556: NCA Profile: 61 Shropshire, Cheshire and Staffordshire Plain, PDF

https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/6076647514046464?category=587130

National Character Area 62 – Cheshire Sandstone Ridge

Description

https://nationalcharacterareas.co.uk/cheshire-sandstone-ridge/description/

Key Facts and Data

https://nationalcharacterareas.co.uk/cheshire-sandstone-ridge/key-facts-data/

Analysis: Landscape Attributes and Opportunities

https://nationalcharacterareas.co.uk/cheshire-sandstone-ridge/analysis-landscape-attributes-opportunities/

NE551: NCA Profile: 62 Cheshire Sandstone Ridge, PDF

https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/5228198174392320

Sandstone Ridge Trust

Maiden Castle: An Iron Age cliff edge fort (2-page PDF leaflet)

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/lib/file-323322.pdf

Circular walks that include hillforts of the Cheshire Sandstone Ridge

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/discovering/walks-february.html