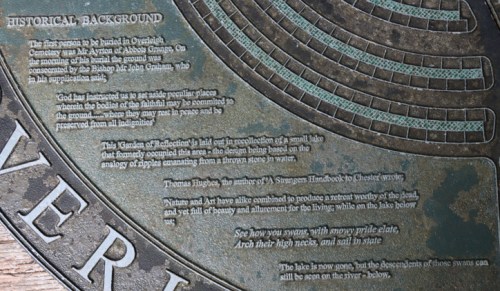

Interpretation board at Haughmond Abbey. The “You Are Here” text at far right (the south end of the site) marks the location of the interpretation board. The church remains only as a few courses of stone at far left (north) but leaves a clear footprint of its layout.

One of the fascinating ruined monastic buildings that I visited during my October 2024 trip to Shropshire, was the sprawling Haughmond Abbey, just a few miles northeast of Shrewsbury, and very easy to reach. The Romanesque survivors at the site are particularly delightful, giving the site a charm and subtle glamour that is largely missing from most of the somewhat repetitive gothic establishments that followed.

Haughmond was the first Augustinian monastery that I have visited, and it is unusual in being so large for an Augustinian establishment. The followers of St Augustine of Hippo, also known as Austins or Black Canons, followed a rather different set of guidelines from those of the Benedictines, Cluniacs and Cistercians and others who followed the Rule of St Benedict, of which more below. Most Augustinian monasteries were priories, but Haughmond was raised from a priory to an abbey in the mid-12th century, one of only 9 in England to do so, and its ground plan is extensive. Its design borrows extensively from its St Benedict-inspired predecessors, but there are notable differences too.

The visible remains of Haughmond relate to the buildings founded as an Augustinian abbey in the 1130s, dedicated to St John the Evangelist. Some documentary evidence is supplied by what remains of its cartularies (collection of charters) assembled between 1478-1487 as well as records of leasing agreements from the 14th to the 16th century, both of which provide information about its economic activities from the 12 century onward. Further information was provided by excavations. The first of these were carried out by William St John Hope and Harold Brakspear in 1907, and were interestingly financed mainly by public subscription, reflecting local interest in the site. Part of this was clearance of debris but they found the remains of the 11th century church and revealed many of the remains of the early church and priory. When the Ministry of Works in 1933 took over the site they too undertook clearance works and further excavations, at the south end of the site, took place in 1958 . In the 1970s, Jeffrey West and Nicholas Palmer concentrated on the various phases of the abbey church and and surveyed the abbey’s surviving walls. In 2002 a survey by English Heritage not only found the location of the original gatehouse but located the abbey precinct’s boundaries and many of the features that lay within those boundaries, including important aspects of the drainage system.

The visible remains of Haughmond relate to the buildings founded as an Augustinian abbey in the 1130s, dedicated to St John the Evangelist. Some documentary evidence is supplied by what remains of its cartularies (collection of charters) assembled between 1478-1487 as well as records of leasing agreements from the 14th to the 16th century, both of which provide information about its economic activities from the 12 century onward. Further information was provided by excavations. The first of these were carried out by William St John Hope and Harold Brakspear in 1907, and were interestingly financed mainly by public subscription, reflecting local interest in the site. Part of this was clearance of debris but they found the remains of the 11th century church and revealed many of the remains of the early church and priory. When the Ministry of Works in 1933 took over the site they too undertook clearance works and further excavations, at the south end of the site, took place in 1958 . In the 1970s, Jeffrey West and Nicholas Palmer concentrated on the various phases of the abbey church and and surveyed the abbey’s surviving walls. In 2002 a survey by English Heritage not only found the location of the original gatehouse but located the abbey precinct’s boundaries and many of the features that lay within those boundaries, including important aspects of the drainage system.

====

The Augustinians

The earliest known representation of St Augustine from the 6th Century in the Lateran, Rome. Source: Wikipedia

The Augustinian order, like the traditional medieval monasticism that subscribed to the ideas of 6th century St Benedict, looked to an earlier time and an earlier authority on which to base their own approach to monastic living. St Augustine (354–430) was born in Roman North Africa in 345. Before a visit to Milan he had been closely associated with the Manichean religion before meeting Christian intellectuals in Milan. On his return to North Africa his own inclination as a Christian was to embrace the monastic life, but he was persuaded to take orders as an ordained priest, partly because Christianity was a minority religion in the area at that time, and although he accepted this role, he also received permission from the bishop of Hippo (now Annaba in Algeria) to create a community of Christian men and women who renounced wealth in favour of a communal life of religious service. He later became the bishop of Hippo himself.

Augustine’s guidelines were not written down as a single set of rules like those of St Benedict, but were assembled from a letter to his sister a nun, which offered thoughts on how a monastic establishment should be run. These had no influence on the development of monastic life until the 11th century and it is not known whether the rule itself was rediscovered or whether Augustine’s ideas were simply adopted from his other extensive writings to create a rule carrying the saint’s authority, applicable not only to monasteries but other religious communities, including hospitals.

The Augustinian monastic organization was founded in the 11th century, with papal approval. Its monks were popularly known as the Black Canons, canons being members of a monastic community of priests. Unlike those monastic orders based on the Rule of St Benedict, the Augustinians, or Austins, were ordained priests and were able to leave their monastery to work in the community to carry out pastoral work. The foundation of hospitals was also an integral part of many of the Augustinian establishments.

The Augustinian monastic organization was founded in the 11th century, with papal approval. Its monks were popularly known as the Black Canons, canons being members of a monastic community of priests. Unlike those monastic orders based on the Rule of St Benedict, the Augustinians, or Austins, were ordained priests and were able to leave their monastery to work in the community to carry out pastoral work. The foundation of hospitals was also an integral part of many of the Augustinian establishments.

The central ideas of the rule by the 12th century were that canons should emulate the apostles, abandoning their possessions, leading a celibate, contemplative life that included prayer, in which personal poverty, self-discipline, mutual responsibility and charitable generosity were more important than austerity and seclusion. Augustinian canons could spend time in the community and conduct services in churches. The maximum number of canons permitted in a single establishment was 24, and at the time of the Dissolution there was half this number at Haughmond. No two establishments necessarily operated in the same way, although many of the monasteries shared the basic Benedictine layout of the main buildings gathered around cloisters. Many were very small, usually holding the status of priory, but Haughmond was promoted to an abbey early in its history. It was unusually large, and was gathered around two cloisters, as well as an infirmary, now lost.

==

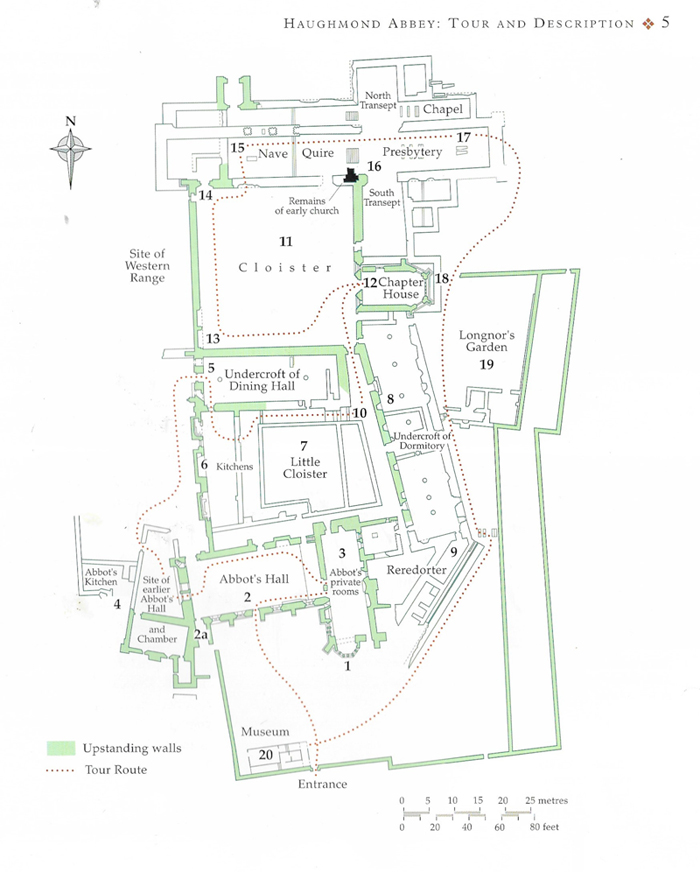

Entering the site today – orienting yourself

The site is entered from the south where the Abbot’s Hall, private rooms and reredorter (latrine block) are located (at the bottom of the plan at left). In the medieval period all visitors would only have entered at the opposite end of the site, to the north, where the remains of the church and its two transepts are to be found. The monastic complex is an integrated whole, incorporating both domestic and religious functions in a single unit, although it grew up over time, advancing from north to south, beginning with the church, in the opposite direction from which you enter. Repairs and reinventions mean that there are many layers to understand within the abbey complex.

Sandwiched between the Abbot’s Hall at the south end of the monastery and the church at the north end are two cloisters (square arrangements of buildings, each around a central green area). The two cloisters are separated by the frater (refectory) that makes up the north wall of the southern cloister and the south wall of the northern one.

The official guidebook has a recommended circular route either straight ahead from the entrance, via the Abbot’s Hall, or via the reredorter (latrine block) to the right. It does help to have a site plan to walk with, either in the guide book or printed out, particularly given that even with experience of previous monasteries, it’s a complex site with some features only surviving to the height of a few courses of stone.

==

The development of Haughmond Abbey

A splendid reconstruction of Haughmond Abbey by Josep Casals for English Heritage / Historic England. Source: English Heritage. My annotations based on the plan shown in the Haughmond Abbey guidebook. North is to the left, where the church is located. Click to enlarge

Like most high-status buildings, Haughmond changed considerably over time. It began in the 11th century as an isolated community. The reasons for the location have not been recorded but the English Heritage survey of the site suggests the following:

[T]he comparative remoteness of the area on the woodland fringe, the shelter provided by the slope and the ready availability of building stone are all valid explanations. However, these conditions apply widely along the foot of Haughmond Hill and so it was probably the occurrence of a number of springs along this particular section of the escarpment which was the determining factor. The need for a reliable water supply for drinking, washing and carrying away waste hardly needs stating but there is also the possibility that the first community chose to settle here because the springs already had an established spiritual significance. (Pearson et al 2003)

Small entrance to Haughmond Abbey from the south, now the entrance for visitors. The main gateway was at the north.

One of the important achievements of the combined excavations was to establish that an earlier abbey had preceded the 12th century Augustinian priory. The remains of a small cruciform stone church were found beneath the south transept and the northeast cloister and it is suggested that it may have been built by an eremetical community, either in the late Saxon or early Norman period. A small cemetery of 24 graves that was found immediately to the west of that church included child burials, suggesting that it was serving the community at large, not merely the monastery.

The monastery was later re-established by the FitzAlan family under William FitzAlan I in the 1130s as a priory using the Rule St Augustine to guide its activities. This included rebuilding of the church and cloister that provided the Augustinian priory an integral part of its later identity. It was so richly endowed that it was soon given abbey status. The FitzAlan family continued to be patrons of the abbey and were buried at the site until the mid-14th century. They eventually transferred their loyalties to another establishment when the Lestrange family took over as primary patrons, their endowments allowing further expansion. During the 13th and 14th centuries further elaborations were made, and in the early 16th century it underwent remodeling, just in time for the Dissolution in 1535.

Information panel at Haughmond showing the daily liturgy followed by the Black Canons. Click to enlarge

As a wealthy abbey, Haughmond was not amongst the first to be closed down, and lasted until 1539, at which time the remaining community members were pensioned off. After it had been plundered for its treasures for Henry VIII’s coffers the abbot’s quarters were converted to a country home for Sir Edward Littleton, with some of the other buildings remaining in use. It continued to be a home until the Civil War when a fire put an end to its residential use. It was eventually handed over to the Office of Works in 1933. The 2002 survey by English Heritage established the extent of the abbey precinct and identified its water management systems, neither of which had been fully understood before. The excavations found numerous objects, Romanesque architectural stonework, human remains, animal bones, pottery and metalwork all dating to the abbey’s occupation.

==

The Abbey Layout

The preservation of the buildings is very variable, with the abbot’s residence and hall and chapter house being the main and very impressive survivors. The inner wall of the west range survives, and there are some fascinating architectural details dotted around, but most of the site is represented by low courses of stone that reach only a few feet high. This does not undermine the visit, because these lower courses preserve the layout of a complex site, which offers a great many insights into life at Haughmond.

The monastic precinct

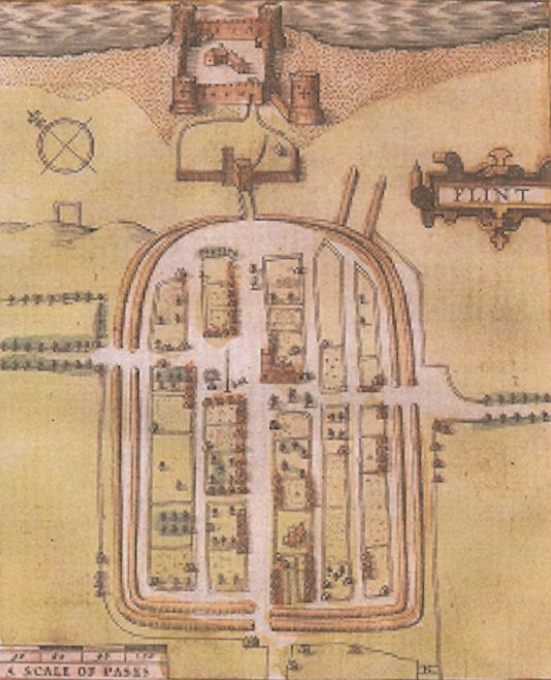

Plan of the abbey in the 2002 survey. Source: Pearson et al survey report 2003, English Heritage (see Sources at end).

The site is large, but only represents the core buildings. The monastic precinct was much bigger. Access to the monastic precinct would have been via the main gatehouse. The remains of this was found in the 2002 survey, to the west of the church. The boundaries of the monastic precinct were not found in 1907, but were revealed by the 2002 English Heritage survey. This provided a good idea of the full extent of the site, making it easier to visualize it beyond its current footprint, and at the same time offered an entirely new interpretation of the site’s drainage management, always an important aspect of monastic establishments which, as well as requiring fresh water, had waste management and other drainage requirements.

The church

Haughmond Abbey Church interpretation panel. The sacred east end with the presbytery/chancel is on the left, with the nave to the west on the right, and a dividing screen between them. Click to enlarge.

Although there is nothing left to give an idea of how the interior would have looked, the very lowest courses of the church retain its footprint, and excavations have provided some more information, derived from the masonry of the site. The church had the usual cruciform plan of a long nave, short chancel, two side transepts, 60m (200ft) long in total, with a short tower over the crossing. Visitors would have entered into the nave of the church via the north porch, penetrating no further than the church nave. The nave was divided from the sacred east end of the church by a stone screen. The cloister and the rest of the monastic establishment would have been completely out of bounds for ordinary visitors. The canons would enter from the cloister side. Interestingly, the site is terraced beneath the line of the church, meaning that the altar would have been physically higher than the transepts, involving a great many steps to reach the high altar, which would have been higher than the nave, emphasizing the hierarchy of the church from sacred east to secular west. The transepts would have contained chapels where the ordained priests could say masses to the dead. There were also altars, other than the main altar, to St Andrew and St Anne. An aisle was added to the north side of the nave, the pier bases of which were found during the 1907 excavations.

The main cloister

The church makes up the north side of the cloister, offering it some protection from the elements and allowing in the sun, which helped to light both the church and the cloister buildings. The main cloister was rectangular and the other three sides were made up of three ranges of buildings with a green, the garth, at its centre. Nothing remains of the walkway that would have connected these four ranges of buildings.

Connecting the cloister or the nave was the processional doorway, a magnificent 12th century feature through which the monks could carry reliquaries, saint images and portable shrines on days of particular religious significance. Like the chapter house, it has elaborate patterning on the out of the recessed arches and is flanked by two statues representing St Peter (left) and St Paul (right).

The most important building in the east range, which is partly made up by the north transept of the church, is the chapter house, where the daily business of the monastery was discussed. Its lovely facade includes the entrance flanked by two windows, all with receding layers of arching featuring decorative patterns, and featuring eight statues showing saints between the slender columns. Although the arches belong to the 12th century, the statues were added in the 14th. Some are in rather better condition than others, but include St Augustine, a female saint who perhaps represents St Winifred of Shrewsbury Abbey, St Thomas Becket, St Catherine of Alexandria, St John the Evangelist, St John the Baptist, and St Margaret of Antioch. The building underwent further changes at the beginning of the 16th century, probably including the addition of a wooden ceiling. The tombstones and the font were probably moved here from the church after the monastery went out of use.

Opposite the chapter house is what remains of the western range. The inner wall survives, with two tall arched recesses, which probably contained a laver, a basin that the monks used for washing before eating. Further along at the northern end adjacent to the processional doorway an entrance lead into the western range, with decorated capitals at the top of the columns. The outer walls have been lost. The western range was used differently from one establishment to another, and it is not known how this example was used.

The southern range was made up of the refectory (dining hall) with an undercroft (storage area) below. The floor of the dining hall is long gone, but some decorative features remain in the walls, and it once had a great window over a central pointed arch. The undercroft opened out into the monastic precinct via an arched entrance and and two flanking windows. The remains of the pillars that supported the refectory wall remain, together with a drain running towards the north. The full length of the refectory was 30ft 6ins (c.9m) wide by c.81ft (c.25m) long.

Behind the chapter house and overlapping with half of the dormitory is what is known as the Longnor’s Garden, now an empty space with a wall behind it, established in the mid-15th century for Abbot Longor. As well as a dovecote it was presumably used to grow herbs, for both cooking and medicinal use.

The little cloister

A narrow gap at the east end of the refectory allowed access from the main cloister into the little cloister. A low line of stone marks the line of the former walkway that surrounded the little cloister. This contained another four ranges, the northernmost of which was made up by the refectory. The entrance to the refectory was probably originally from the main cloister, but once the little cloister was established, the entrance was on this side, which makes sense as the early 14th century western range consists of a surprisingly large kitchen area with two giant ovens and chimneys. The 1332 document by Abbot Longnor that permitted this survives, stating that the prior and monastic community “may have from henceforth a new kitchen assigned for the frater, which we will cause to be built with all speed ; in which they may cause to be prepared by their special cook such food as pertains to the kitchen of that which shall be served to them, every day, by the canons and ministers appointed to that end by them by leave of the abbot.”

The kitchen and refectory, side by side. To the left of the refectory wall, and in front of the ovens is the line of little cloister’s walkway.

Opposite the kitchens were the two-storey dormitory and its undercroft, set at an angle to the little cloister and terminating at the south side with an entrance into the reredorter (latrine block), which was set at an angle to the dormitory. The undercroft survives, but the upper levels that made up the dormitory are now lost. The building is 125 ft long by 27 ft wide, with a row of columns along the centre, dividing it into eleven bays. The remaining stonework preserves indications of doorways, windows and fireplaces. In the mid-15th century the north end of the dormitory was divided off to provide private space for the quarter’s of the abbot’s second in command, the prior.

At the southern end of the little cloister were the abbot’s apartments, consisting of a hall and private rooms. The remains of an earlier and much smaller set of13th century apartments survives at the east, but was replaced by the much more ambitious, decorated 14th century buildings that partly survive today. The main feature of the hall is an enormous pointed window, with fragments of stone tracery remaining, set over twin pointed arches, and flanked by two small towers. Three sets of windows, with tracery, let light in on either side, and again provide the rooms with gothic flair. The Abbot’s private rooms feature a distinctive 5-sided oriel window with distinctive decorative elements.

=

Records mention an infirmary at Haughmond, as well as a library. The library would usually be closely associated with the chapter house, but there is no sign of one today. In early 20th century plans the infirmary is marked where the abbot’s hall is now located, and the infirmary has not actually been located. The consensus is that the local topography means that it could not have been to the east of the site. Two fishponds were not far away, and others were associated with mills.

====

Economic activities

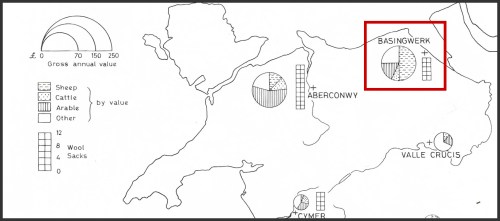

Although patrons were important for establishing monastic establishments and continuing to support them, many of the endowments took the form of land, and the success of a monastery was largely dependent on how well that land and other assets were managed. There were two main models for making an income from these assets – either by the owners working it themselves or by leasing it out. In the case of Haughmond the assets included considerable amounts of farmed land, as well as fulling (wool processing) and corn mills. Although lying within a royal forest, the abbey was given limited permission to assart land (clear woodland and shrubs for farming), and also acquired newly assarted lands in the area. It owned land under cultivation but also established cattle farming on higher ground. Lands were not only in Shropshire but from the late 12th century it also owned land in Cheshire, Worcestershire, Wales, Sussex and Norfolk. Fishing rights were also important, and the abbey had its own fishponds, as well as fishing rights both nearby and from the river Dee at Chester, the latter doubtlessly annoying the Benedictine monks of St Werburgh’s in Chester. It also received income from six churches that had been passed to its control, including Hanmer in Flintshire, the only one outside Shropshire; it had properties in Shrewsbury that it rented out; and was granted the rights to and a one half salt-pan in Nantwich.

Many small bequests were made to secure prayers, to assist the infirmary and to provide for the poor who came to the monastery gate for alms. The monastery also sold corrodies, which were substantial gifts made to the monastery in return for food and housing, a form of pension. On the other hand, corrodies were also provided to loyal servants, in which case they represented an outlay rather than an income.

It is thought that between the 13th and early 14th centuries the abbey restructured in order to consolidate the dispersed properties to make them easier to manage, something that happened at a lot of other monastic establishments that found themselves in this situation, causing real management difficulties. By selling some lands and acquiring others in more suitable locations, consolidation made management much easier and less costly. At least some of the land was leased out, but other lands were worked directly, However the surviving records are insufficient to allow a clear view of how well the abbey managed its assets, how all of its lands were used and what sort of activity provided the most income.

In spite of the recorded assets, in the early 16th century the abbey clearly experienced difficulties, both in the management of its estates and in the internal discipline of the monastery itself. This is put down to poor management by two of its abbots. Under its final abbot, Thomas Corveser, it began to recover and it was still sufficiently wealthy to avoid immediate closure in 1535, surviving another four years, and the surviving personnel were provided with generous pensions.

==

Final Comments

This is a very quiet site, and because it feels so peaceful and retains some lovely features of its 12th century Romanesque origins, has a particular charm to it. I particularly like that some of the domestic buildings that rarely survive at other sites, including the vast hearths in the former kitchen, and the reredorters connected to the dormitory, can be clearly made out. I was expecting the Augustinian arrangement to have significant differences from Benedictine prototypes, but there was nothing much on the ground to differentiate them. The decorative features certainly mark them out as less austere than, for example, the Cistercians, but otherwise the architectural concept of a monastery in the medieval period is impressively uniform.

This is a very quiet site, and because it feels so peaceful and retains some lovely features of its 12th century Romanesque origins, has a particular charm to it. I particularly like that some of the domestic buildings that rarely survive at other sites, including the vast hearths in the former kitchen, and the reredorters connected to the dormitory, can be clearly made out. I was expecting the Augustinian arrangement to have significant differences from Benedictine prototypes, but there was nothing much on the ground to differentiate them. The decorative features certainly mark them out as less austere than, for example, the Cistercians, but otherwise the architectural concept of a monastery in the medieval period is impressively uniform.

==

Visiting

Haughmond Abbey is an English Heritage site. It was open free of charge when I was there in October 2024, but its opening times and ticket prices may vary with the season. See details on the English Heritage website here. The postcode for those of you with SatNav is SY4 4RW. The guide book, published in 2000, claims that the little building on the left as you enter is a museum, but this was very firmly closed when I visited. Perhaps it is open during the summer, or it may have shut down for good by now. Please let me know if you find out!

There are interpretation boards throughout the site, which help to explain it. The helpful guide booklet by Iain Ferris is available from online retailers, but may also be available from English Heritage sites with gift shops in the area. It combines Haughmond, Lilleshall and Moreton Corbet Castle in the same 24-page booklet, with 14 pages dedicated to Haughmond and the Augustinians, 8 pages to Lilleshall and 2 to Moreton Corbet Castle. It includes the ever-essential site layouts of Haughmond and Lilleshall. There are also very useful details about the history of the site on the English Heritage’s Haughmond Abbey History page here. If you are interested in following a trail of some of the Shropshire abbeys including Haughmond, Mike Salter’s booklet “A Shropshire Abbeys Trail” is a good place to start, available to purchase online.

There are interpretation boards throughout the site, which help to explain it. The helpful guide booklet by Iain Ferris is available from online retailers, but may also be available from English Heritage sites with gift shops in the area. It combines Haughmond, Lilleshall and Moreton Corbet Castle in the same 24-page booklet, with 14 pages dedicated to Haughmond and the Augustinians, 8 pages to Lilleshall and 2 to Moreton Corbet Castle. It includes the ever-essential site layouts of Haughmond and Lilleshall. There are also very useful details about the history of the site on the English Heritage’s Haughmond Abbey History page here. If you are interested in following a trail of some of the Shropshire abbeys including Haughmond, Mike Salter’s booklet “A Shropshire Abbeys Trail” is a good place to start, available to purchase online.

Other sites in the area, a selection of which would help to make up a good day out include Wroxeter Roman City (about which I have posted here), the Cluniac Order’s Wenlock Priory at Much Wenlock (posted about here), another Augustinian abbey at Lilleshall, Moreton Corbet Castle, and of course the town of Shrewsbury itself, with its lovely architecture, terrific abbey church (within the outskirts of the town) and the excellent Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery. with its modern displays connecting different periods of the history of both town and area.

Sources

Books and Papers

Angold, M.J. Angold, George C. Baugh, Marjorie M. Chibnall, D.C. Cox, D.T.W. Price, Margaret Tomlinson, B.S. Trinder 1973. Houses of Augustinian canons: Abbey of Haughmond, in (eds.) A.T. Gaydon, and R.B. Pugh. A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2. London.

Angold, M.J. Angold, George C. Baugh, Marjorie M. Chibnall, D.C. Cox, D.T.W. Price, Margaret Tomlinson, B.S. Trinder 1973. Houses of Augustinian canons: Abbey of Haughmond, in (eds.) A.T. Gaydon, and R.B. Pugh. A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 2. London.

British History Online: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/salop/vol2/pp62-70

Burton, Janet 1994. Monastic and Religious Orders in Britain. Cambridge University Press

Chadwick, Peter 1986. Augustine. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press

Levitan, Bruce 1989. Ancient Monuments Laboratory Report 118/89. Vertebrate Remains from Haughmond Abbey, Shropshire. English Heritage

https://historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/3917/VERTEBRATEREMAINSFROMHAUGHMONDABBEYSHROPSHIRE

Pearson, Trevor, Stuart Ainsworth and Graham Brown 2003. Haughmond Abbey, Shropshire: Survey Report Archaeological Investigation Report Series AI/10/2003. English Heritage

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1893-1/dissemination/pdf/englishh2-349481_1.pdf

Salter, Mike 2009. A Shropshire Abbeys Trail. Folly Publications

St John Hope, William H. and Harold Brakspear 1909. Haughmond Abbey, Shropshire Archaeological Journal, 66 (1909), p.281–310

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1132-1/dissemination/pdf/066/066_281_310.pdf

White, Carolinne 2008. The Rule of St Benedict. Penguin

Ferris, Iain 2000. Haughmond Abbey, Lilleshall Abbey, Moreton Corbet Castle. English Heritage

West, Jeffrey J. and Nicholas Palmer 2014. Haughmond Abbey. Excavation of a 12th-century cloister in its historical and landscape context. English Heritage

Websites

ArchaeoDeath

Identities in Stone: Haughmond Abbey’s Saints and Spolia. By Prof. Howard M. R. Williams,

October 17th 2016

https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2016/10/17/identities-in-stone-haughmond-abbeys-saints-and-spolia/

English Heritage

Haughmond Abbey

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/haughmond-abbey/

History of Haughmond Abbey

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/haughmond-abbey/history/

Medieval Women and Haughmond Abbey

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/haughmond-abbey/history/women-at-haughmond/

Historic England

Haughmond Abbey: an Augustinian monastery on the site of an earlier religious foundation, a post-Dissolution residence and garden remains

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1021364?section=official-list-entry