On a recent visit to the National Waterways Museum at Ellesmere Port on the Wirral, I noticed a long, dusty glass cabinet with what looked like a big length of seriously traumatized tree trunk inside. Having seen pictures of logboats that looked just like this, but never having seen one on display, I went to have a closer look. Sure enough, it was the Baddiley Mere logboat. In its presumably temporary display position it was hemmed in by other objects and difficult to reach and the cabinet was seriously dusty making it difficult to view properly. Happily an information poster was clearly displayed explaining that this is a nationally important piece of English heritage.

Baddiley Mere Log Boat at the National Waterways Museum, Ellesemere Port, not really living up to its full potential as an exhibit and an artefact of national importance.

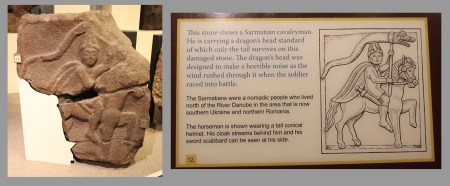

Finds of logboats or dugout canoes (properly known as monoxylous crafts) are comparatively rare, and their survival is always due to environmental conditions that favour their unexpected preservation. The Baddiley Mere log boat is one of a short list of survivors to have been found in the boggy conditions of Cheshire, all of which are discussed below. In western Europe, log boats have been found in the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, France and Scandinavia as well as Britain and Ireland. In Britain, many were found at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, often due to land drainage and water cleaning activities, including all of the Cheshire examples. This post lists the Cheshire logboats, and puts them into the context of British logboats in general.

The environments that preserved the logboat

Artist’s reconstruction of the Poole Harbour logboat, which dates to the Iron Age. Source: Wessex Museums

The relatively small number of logboats discovered relates partly to accidents of survival and partly to accidents of discovery. If you were to look at a distribution map of logboat locations (had I been able to find one), you will be looking at where logboats were found, not the full geographical range over which they were used. Organic remains like bone, wood, leather and reed are so much less commonly preserved than the durable tools made from stone, ceramic and metal that Linda Hurcombe refers to organic objects that must have dominated the human toolkit throughout prehistory as “the missing majority.” Differential conditions of preservation for organic remains means that logboats are only found in very specific environmental conditions.

It is almost certain that logboats were a standard part of the riparian kit during later prehistory, if not before. The waterways were an important communication network over considerable distances, but even when used for purely local activities, boats would have been useful for getting around, crossing rivers and for fishing and capturing wildfowl. The remarkable example of eight logboats found at Must Farm in Cambridgeshire near contemporary eel-traps and hurdle weirs creates a picture of experiments with slightly different forms of boat, in use for everyday activities in the fenland area.

The distribution of logboat finds is confined in Britain to waterlogged environments where oxygen, which enables decay, has been eliminated, and where these waterlogged environments have been preserved for 100s, sometimes 1000s of years. These anaerobic conditions only exist under certain conditions but may be found in meres, swamps, marshes, fens, carrs, riverbanks and deeply silted river and lake beds. Peat deposits, especially waterlogged ones, may be acidic, which hinders bacterial decay and helps to preserve organic remains. Waterlogged acidic conditions are ideal for preservation of wood and plant remains. As organic remains decay rapidly, even something as large as a log boat would have to be buried with anaerobic sediments very quickly, making preservation even more of a challenge.

Discovery is always by accident, at times when activities are taking place to drain or clean waterlogged environments, to dredge silt, to dig up peat, or where hot summers or longer-term climate change desiccates waterlogged areas, exposing wooden items. Other organic items that are found preserved include trackways, platforms for buildings, tools and objects made of bone, wood, leather and reed, and even fabrics.

Cheshire Logboats

The short list below shows the Cheshire logboats, prehistoric and early medieval that I have been able to find information about.

The Baddiley Mere logboat, now in the National Waterways Museum in Ellesmere Port (and formerly in the Grosvenor Museum, Chester), can be visited. The Ciss Green example has been in the Congleton Museum from the museum’s opening in 2002. I have been unable to find if the others are still preserved.

Baddiley Mere

The log boat was found in Baddiley Mere (about 15 miles south west of Nantwich) in 1911, when the water quality in the mere, a glacial lake, was being improved for supply to Nantwich. Baddiley Mere is part of a group of wetlands in the south-west of Cheshire, that lies between between Cholmondeley and the Shropshire border, and they can be associated with areas of peat and other waterlogged deposits.

The Baddiley Mere boat at the time of its extraction in 1911. Source: The The North West England Regional Research Framework: Prehistoric Resource Assessment 2007

It was found in peat deposits at around 6ft c.1.83m) beneath the surface, embedded in the anaerobic conditions that ensured its preservation. It is formed of a single piece of oak and is nearly 18ft (5.5m) long by just under 3.3ft (c.1m) wide. It weighs 458kg. Its slightly distorted shape is due to shrinkage after it was removed from the waterlogged conditions. In 1929 a preserved paddle, about 4ft long (1.21m) was found near the findspot and may (or may not) have been associated with the boat. Rust was found in a hole in the boat, thought to be from a nail. A vertical hole at one end is thought to have been for a mooring rope or for fastening a pole into position.

The Iron Age date suggested by a piece of rust in a nail hole may be indicate that the boat does not predate the Iron Age. There was not a lot to rule out a later date in terms of the features of the logboat itself, but a radiocarbon date suggested a late prehistoric date.

The Baddiley Mere logboat was apparently on display in the Grosvenor Museum until at least 1974, so must have been moved to the National Waterways Museum at Ellesmere Port sometime after that date. See the end of this post, just before Sources, for a link to a TikTok video of Professor Howard Williams talking about the Baddiley Mere logboat.

Warrington 1 and 2, Arpley Meadows

In 1894, just a year after the discovery, Charles Madeley wrote about the discovery of two logboats during the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal:

The construction of the Manchester Ship Canal has been, in one respect, a great disappointment to those who dwell upon its banks. It was only natural to expect that the excavation of so great a cutting for thirty-six miles, through the soil of the Mersey valley, could not fail to result in large discoveries of relics of the former inhabitants of the district, and numerous additions to the contents of our museums. But these anticipations were speedily relinquished on the advent of the steam navvy, whose rapid evolutions and wholesale manner of procedure obviously offered little prospect of the preservation of any but the largest objects which might be in its way. Of such large objects, however, two very interesting examples were the two canoes which were found, not in the course of the canal itself, but on the banks of the Mersey, during certain subsidiary operations at Arpley, in the township of Warrington. . . .

Early in September, 1893, during the completion of the new course for the Mersey which was cut across the Arpley meadows, the dredger came upon an obstruction, which proved to be a dug-out canoe, over ten feet in length. Later, on the 28th March, 1894, another and larger canoe was discovered, at a point 600 yards further east and close to the west end of the present Walton Lock. Each canoe lay 20 to 25 yards north of the former bank of the River Mersey, and at a depth of about eighteen feet below the surface of the ground. On their discovery both canoes were carefully removed and preserved, under the direction of Mr. William Burch, C.E., the Ship Canal Co.’s engineer for this section, and Mr. H. Davenport, who was in charge of the dredging operations when the first discovery was made. The canoes were eventually presented by the Canal Company to the Warrington Museum.

The 1893 logboat (Warrington 1) was the bigger of the two (shown above right), and shows a number of interesting features, described in detail by Madeley. Its length was unbroken and measured 12 feet 4 inches (c.3.8m) long. The width was irregular, 2ft10ins (c.87cm) at the stern and ; the greatest width, near the stern, was about 2ft3 1/2 ins (69cm) from midsection to bow. The depth was also slightly irregular, at around 15ins (38cm) at the stern and 12ins (31cm) at the bow. The timber of the base is around 2ins (c.6cm). Two internal ribs remain on the floor of the boat, as shown in the above diagram. The ends of the boat are rounded, inside and out, both in plan and section, but it not known whether there was what Madeley refers to as “a projecting nose,” like that on the smaller canoe. At each end there is a section of gunwale and at the stern end some timber waling fastened down with four trenails an inch (c.2.5cm) in diameter. Indentations in the stern suggests the presence of a plank perhaps serving as a seat or a standing platform at the stern end, clearly visible in the top of the sketches.

The 1894 Walton Lock logboat (Warrington 2) was discovered (shown above left) and this was smaller and of a slightly different form. It measures 10 feet 8 1/2 ins (c.3.30m) in length and was probably about 2ft 9ins (c.84cm). Its depth was about 14 inches (c.36cm) and the rounded bottom was in places as much as 4 inches (c.11cm) thick. It features “an overhanging nose or prow, the remains of which project some three inches beyond the stem.” The bow has a vertical auger-hole on the starboard side, which may suggest a waling-piece similar to that other logboat. The timber was oak and “very free from knots.”

Radiocarbon dates listed by Switsur suggest that they are Anglo-Saxon, placing them in the second half of the first millennium A.D.

Warrington Logboat 3 (Corporation Electrical Works)

One of the Warrington logboats found at Arpley, although I don’t know which one. Source: Festival of Archaeology 2022

The Heritage Gateway entry record is as follows:

Logboat found in dredging the Mersey opposite the Corporation Electric Works in 1908. It is 10 ft 3 inches long (3.14m) x 2 ft 8 ins (0.80 metres) wide and 1 ft 7 inches (0.48 metres) deep ). One side and some of the bottom have been lost. Made from oak it has a radiocarbon date of around 875 AD.

Warrington Logboat 4 (Corporation Electrical Works)

The Heritage Gateway entry record is as follows:

Logboat found in 1922 in works on the north bank of the Mersey at the Corporation Electric Works. Boat is 11 ft 6 ins (3.5 metres) long with part of the bow broken off. 2 ft 11 ins (89 cm) wide and 20 ins (50 cm) deep. It was covered by 20 ft (6 metres) of river sand, mud and earth. Found in association were two rows of alder stakes forming a fore-runner of the later ‘fish-yards’ or traps It has a radiocarbon date of around 1072 AD.

Warrington Logboat 5, Arpley

The Heritage Gateway entry record is as follows:

Logboat dredged from the old river channel near its junction with the diversion at Arpley in 1929.It is 11 ft long (3.35metres) x 2 ft 4 ins wide (71 cm) and 22 ins deep (56 cm).It is damaged and may have been longer.The find spot is only a few yards to the east of the find spot of Warrington logboat 2. It is made of oak and has a radiocarbon date of 958AD.

Warrington Logboat 7, Walton Arches

The Heritage Gateway entry record is as follows:

Logboat dredged from the Mersey, west of the central pier of Walton Arches in 1931 though it probably came from the vicinity of the junction of the river diversion where other logboats have been found. It is 13ft 6ins long (4.11 m) x 2ft wide (61 cm). Made of oak it dates to 1090 AD.

Warrington Logboat 11, Gateworth

The Heritage Gateway entry records this piece of a logboat as follows:

Logboat found in 1971 at Gateworth sewerage works, near Sankey Bridges. The boat is made from elm and was found at a depth of 3.3 metres in coarse sand. The end is rounded and has a protruding ‘beak’ through which there is a horizontal hole. A radio carbon date of 1000AD has been given.

Cholmondeley 1 and 2

The discovery of the logboat found in a peat bog below Cholmondeley Castle was found in 1819 and published in the Chester Chronicle in the same year. It was reported to be 11ft c.3.35cm) long and 30 inches (c.76.2cm) wide, but very little additional information is available on the subject other than that it was hollowed out of the trunk of a single tree. Although initially believed to be Iron Age in date, it is more likely to be of a similar date to other Cheshire logboats that lie in the date range from the eighth to thirteenth centuries AD. A second Cholmondeley logboat is mentioned on the Heritage Gateway website, but the link to it is broken (SMR/HER 525/2).

Ciss Green Farm, Astbury, near Congleton

The Ciss Green Farm, Astbury logboat on display at the Congleton Museum. Source: Wikipedia. Photograph by Ian Dougherty ex oficio Chairman of the Board of Trustees Congleton Museum

Found in 1923 by farmer Charles Ball during gravel digging near the source of Dairy Brook, the Ciss Green logboat was found near Asbtury, and was stored in the basement of the Manchester Museum until it was eventually moved to the new Congleton Museum in time for the museum opening in June 2002, where it was one of the star attractions. The Museum website does not appear to mention it, so I do not know if it is still there.

Its original measurements are unknown because one end was broken off, but it was made of oak and was nearly 12ft long (c.3.66cm) when found It had a square cross-section with vertical sides. Two holes in the boat have have held oars. Although it was assumed to be prehistoric when it was found, Switsur’s radiocarbon dating puts it in the Anglo-Saxon period at around 1000BC.

Oakmere, near Delamere

In September 1935 an oak logboat was discovered by during extraction of water from Oakmere in September 1935, which lowered the level of the mere. Frank Latham’s local history book on Delamere happily contains a first hand account of the discovery by the gamekeeper George Rock, who had lived there since 1910. Rock noticed what was the prow sticking up out of the shallow water and recognized that it was something man-made. He reported it to his employer, and in due course Professor Robert Newstead of Liverpool University was brought in to supervise excavations.

The Oakmere logboat at the time of its discovery. Source: Cheshire Archaeology News, Issue 4, Spring 1997, p.2

The logboat was found to be lying on a bed of glacial gravel and silt. At that time it survived to its full length of c.3.6m (dsfdsfds) with a width of 0.79m (sdfsdf) but following removal from its waterlogged habitat, which had preserved it, it became fragmentary. Newstead published a paper about it stating his opinion that it was at least 2,000 years old, probably associated with the nearby Oakmere Iron Age hillfort. Eventually radiocarbon dating carried out by Professor Sean McGrail provided a date range between 1395 and 1470 AD.

A site visit described on the Heritage Gateway website found that both the vegetation and the shoreline had altered considerably since discovery and it was therefore impossible to identify the exact find site. Apparently the landowner Captain Ferguson, who had photographs of the boat as it was found, “waded into the lake and endeavoured to identify the site by means of photographs of the boat in situ. He used detail which was between 250 and 600 metres distant, and was identifiable on the ground and on the photograph. He estimated that the find site was at SJ 5731 6768.”

The canoe was sent on loan to the Grosvenor Museum and then in 1979 or 1980 it was sent on loan to the Maritime Museum at Greenwich. The National Museums Greenwich Collection Search website confesses to owning a piece of logboat from Llyn Llydaw, but makes no mention of one from Cheshire, so its current location remains unknown.

Other submerged wooden constructions

Other significant constructions made of wood have been found in Cheshire in waterlogged environments such as at Lindow Moss in Wilmslow and Marbury Meres near Great Budworth, both of which produced evidence of prehistoric trackways, another important means of communication and local resource exploitation. At Warrington, during the works for the Manchester Ship Canal, pilings were found that suggested the presence of a wharf, although it is unclear if these were contemporary with the logboats found.

—-

Dates

List of radiocarbon dates from the north of England. I have highlighted those from Cheshire in pink. Source: Switsur 1989, p.1014. N.B. Switsur also gives dates for the rest of England, Wales and Scotland on subsequent pages.

Although their simple design and overall similarity of appearance often lead to the assumption that the logboats are prehistoric, it has been demonstrated by radiocarbon dating that log boats were far more common during the Anglo-Saxon and later Medieval periods, whilst in Scotland they may have been in use as late as the 18th century.

In his 1989 paper on the dating of British logboats, from which a table of the logboats from the north of England is shown right, Roy Switsur comments:

The general condition of the vessels together with lack of bark or sapwood seems to make dendrochronology [tree ring dating] of less practical use for these objects than at first imagined, so that, thus far, the chronology for the boats has depended on radiocarbon measurements. 14C determinations of several early craft from England and other regions of Europe have been published and reviewed . . . and these have shown that some of the boats originate as late as the Medieval period.

Graph showing the distribution of radiocarbon dates for British logboats of all periods. Source: Lanting 1998, p.631

An additional difficulty with logboat dating is that early attempts to preserve boats that were taken out of bogs and meres in the late 19th century and early 20th century used substances that changed the composition of the wood and made radiocarbon dating difficult if not impossible.

The earliest example is not a boat but a paddle made of Betula (birch) that would have accompanied a boat, found in 8th millennium BC contexts in the Mesolithic environs of Star Carr. In his 1998 survey of logboat dates in Europe Lanting estimates between 350 and 400 recorded logboats in Britain and Ireland, but of these the prehistoric examples are a very small minority, with the majority of the earliest dating to no earlier than the Neolithic, most appearing in the Middle Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age (dates in the 4th millennium BC).

——–

The manufacture of a logboat

A reconstruction of how the Poole logboat may have been built. Source: Berry et al 2019 e-book

Most surviving logboats were constructed from the trunks of the oak, probably because of the hardness and enduring properties of the wood. However, it is probable that many other types of tree were also used for boat construction, as suggested by the elm example from Warrington. Even though softer woods would have been less durable and more prone to damage, they would have been easier to hollow out and carve into shape. Unfortunately softwoods are much less likely than hardwoods to survive as well after deposition.

The skills required for the hollowing out of tree trunks would have represented a fairly mundane activity, although the cutting down of a live tree for use of a whole trunk would have meant different things at different times. A paddle dating to the 8th millennium BC at Star Carr in the Mesolithic was made at a time when wood was plentiful and had not yet been cleared for agricultural activities. By the later Bronze Age and Iron Age the use of a whole live tree for a single boat would have represented more of a pause for thought. Cut marks are preserved on some boats, suggesting how they were carved and what sort of tools might have been used.

A logboat from Must Farm Cambridgeshire, showing features within the hollowed out section. Source: Must Farm Flickr page

All of the boats described as log boats are carved from a single piece of wood, which in Britain is usually oak. Some may have been burned to assist the shaping processes. Although many were not elaborated any further, some were carefully shaped to improve their movement through the water, and some were provided with additional features to improve the usability of the logboats. Even those of a similar date may have very different features in terms of bow and stern shape, holes and fittings. Most have been found in association with inland waterways, lakes, meres, marshes and estuaries, where the shallow and calm waters were suitable for such vessels, and were almost certainly fabricated as near to the shoreline as possible to prevent the very heavy boat having to be dragged too far.

The means for propulsion would have been made at the same time. Logboats could have been either rowed, punted with a pole, or paddled, and a small number of paddles have indeed been found, but not in unambiguous association with logboats. The annual lighter (unpowered barge) races on the Thames show the power of using a combination of oars to row with a paddle at the rear to steer.

It would be surprising if an enterprising person or group had not made the attempt to manufacture a copy of one of these boats, and sure enough The Promethsud Project at Butser Experimental Farm made a logboat using a tree that had come down in the 1987 storms. More recently, the BBC in October 2023 reported that an experimental build was underway in Northamptonshire, part of a £250,000 Heritage Lottery project. Replicas of traditional Bronze Age tools and techniques are being used, including fire, and it is hoped that the two logboats will launched later in 2024.

Experimental reconstruction of a Bronze Age logboat. Source: BBC News

In his book Making, Tim Ingold draws attention to the creation of objects and built environments as a process in which people become involved with materials,during which objects become part of a seamless relationship with their makers. As cultural items, fully integrated both into ways of thinking as well as ways of doing during manufacture, lifetime and at the point of disposal, logboats would have been tied in to perceptions about materials, landscapes, waterscapes and the ability to travel.

Potential uses of logboats in daily life

The uses to which the logboats were put were central to livelihood management, such as fishing, traversing rivers, and travelling over short distances. As mentioned above, the Must Farm Bronze Age logboats were associated with eel traps and river captures, demonstrating how the management of waterways was incorporated into resource management techniques.

The truly remarkable state of preservation of fish traps found in association with logboats in Must Farm, Cambridgeshire. Source: Excavator Francis Pryor’s “In The Long Run” blog.

It has been calculated that the well known Carpow logboat could have carried up to fourteen people, or with a crew of two, around one tonne of cargo. The Brigg logboat was found in an estuary inlet in the river Humber (Hull) where it has been suggested that it could have been employed in carrying heavy cargoes such as grain, wood and perhaps iron ore, as well as having a capacity for up to twenty-eight people. These figures give a good indication that log boats really could make a difference for communities that, as well as fishing, wanted to move resources around including, for example, foodstuffs, ceramics, construction materials and people.

Major riparian connections showing how the river network links from Wessex, the Thames valley and the Humber estuary. These are just as valid for prehistoric, Saxon and Medieval periods. Source: Bradley 2019, p.20

More ambitiously, logboats could have been used for longer distance travel, forging and maintaining links between communities in different areas, exchanging gifts or commodities like salt, heavy objects like stone querns, or exotics (items not available locally), or helping to reach valley-based livestock herds, or move communities to new habitats as part of a mobile livelihood system.

There are independent measures of the value of log boats to communities. Even in some prehistoric periods, sacrificing an entire tree for one vessel would have represented something of a commitment, if not a sacrifice. Most communities would prefer to use branches from slow-growing live trees like sturdy wide-beamed oaks for construction work, only killing off the whole tree if it was necessary for particularly large buildings and other important structures. This suggests that the logboat was deemed to be of sufficient value for the sacrifice of a mature live tree to be worthwhile.

That logboats were valued on an ongoing basis has been demonstrated by the extensive repairs that were made to them. Prior to conservation the Carpow logboat was carefully recorded, including taking an inventory of all its features, including the repairs that had been carried out on it.

Repairs that had been made to the Carpow logboat were carefully recorded during conservation. Source: Woolmer-White and Strachan (ScARF)

Bob Holtzman’s tabulation of all the known repairs of logboats, published in 2021, and his analysis of these findings, has recently highlighted that repairs are another lens through which logboats can be understood. He identifies 73 repaired logboats incorporating 128 repairs, dating from the Middle Bronze Age to the post-medieval period. His typology of repairs clearly indicates that every form of damage that could be imposed on a logboat had a corresponding solution, and that considerable trouble was taken to ensure the longevity of these vessels, some repairs being rather ad hoc, whilst others were far more skilled and permanent. You can read his paper online for his full analysis (see Sources below).

Preserving and conserving logboats

Removing sugar crystals from the logboat following preservation. Source: Wessex Museums

Not only do waterlogged conditions make the discovery of logboat and other large wooden items difficult, but ongoing preservation becomes tricky once the item is removed from the waterlogged conditions that preserved it. Many early logboat finds were removed from their waterlogged contexts and put proudly on display, but began to dry out. Cracks formed and fragmentation began to occur, as well as decay. Attempts at preservation were often unsuccessful, and where successful changed the chemical makeup of the vessel, and made radiocarbon dating difficult if not impossible.

Items have to receive special treatment in order to remain above ground. Decisions have to be made about whether it is best to treat the item in order to retain it in for display in a museum, which can be costly, or to return it to the waterlogged conditions in which it was found. Various techniques have been tried. The Carpow boat from Scotland was kept wet as it was recorded but another solution was needed for long-term display It was decided to use a waxy polymer called polyethylene glycol (PEG) which would replace the water in the wood. The boat was submerged in the solution, in three pieces, in a specially made tank, after which it was freeze-dried, which converted the water turning into ice enabling its removal as a vapour. Prior to these measures, the logboat and its contemporary repairs had been recorded in detail using high-resolution digital photography and 3D scanning. The Poole Harbour logboat was also initially kept in water to prevent it drying out and disintegrating, but in the 1990s conservators from York Archaeological Trust came up with the idea of preserving it in over six tons of sugar solution before being dried out in a sealed chamber. The excess white sugar crystals that covered the boat had to be removed manually.

The Medieval Giggleswick Tarn logboat. Source: Leeds.gov.uk

A rather different problem was presented by the Medieval Giggleswick Tarn logboat (North Yorkshire), originally discovered during drainage works in 1863, “which was blown to pieces during a Second World War air raid” in 1941. It was not until 1974 that the fragments of the ash-built vessel were sent to the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich where they were examined and partially re-assembled, and dated to c.1335AD. The Giggleswick Tarn boat was luckier than the Brigg (Hull) logboat which was destroyed in the bombing of the museum where it was on display, suspended from the ceiling, in 1943. In the latter case, all that survives of the boat is the information that was recorded before it went on display.

Prehistoric logboats as special objects

One of eight Bronze Age boats found at Must Farm in Cambridgeshire was decorated, suggesting that particular care was given to the appearance of the boat. Logboats that were used for longer distance journeys and the forging of new connections with other communities have had a special status. Some boats may have been specially created for this purpose, giving them additional prestige and kudos.

Decorated Bronze Age logboat from Must Farm in Cambridgeshire. Source: Must Farm Flickr page

Normally objects that are found isolated and abandoned were discarded at their place of use when no longer needed. They might be deliberately disposed of in middens, broken and swept to the edges of settlements, could be lost to flood or fire or simply dropped by accident and never recovered by their owners. However the deposition of hoards of Late Bronze Age and Iron Age metalwork, like that in Llyn Cerig Bach (Anglesey), and the discovery of an Iron Age preserved body in Lindow Marsh, are associated with the idea of ritual deposition (i.e. deposition of bodies and items connected with specific rites of passage and religious ceremonies). In later prehistory there is often a connection with lakes, rivers and bogs.

The idea that some of the prehistoric logboats might belong to this latter category has been explored by a number of writers, including Joanna Brück, who describes them as objects that had crossed boundaries, and entered liminal spaces, becoming associated with ideas of transformation in the process. In this they might have required a special “ritual decommissioning” process to ensure that any embedded danger or risk associated with the places through which it had past was neutralized, transforming it from active to inert. Logboats may therefore have equally have been lost by accident, or deposited deliberately when, for whatever reason, they went out of use. It is not always easy to tell which was which, but Panagiota Markoulaki makes the attempt in her 2014 PhD thesis (see Sources below), which is available online for anyone wishing to pursue this subject further.

There is a possibility that a small number of prehistoric the logboats discovered were used mainly or exclusively for ceremonial purposes. A logboat from Lurgan in Co. Galway which is over 46ft (c.14m) in length was far too long for practical purposes, being almost impossible to navigate, and may have been used in ceremonial contexts.

Other logboats may have been used as models for burials, or even incorporated into such burials. Boat-shaped burial mounds are known in Britain, and some burials appear to emulate the shape of logboats, with one from Oban (Scotland) apparently having a re-used logboat at its centre. These date to between 2200 and 1700 BC.

Final Comments

Artist’s impression of the Carpow logboat transporting people across the river Tay. Source: Woolmer-White and Strachan (ScARF)

I started this piece after seeing the Baddiley Mere boat knowing almost nothing about logboats, and certainly nothing helpful. It was fairly slow going without access to an academic library, but thanks to some good some excellent papers shared online, some very useful online articles and the occasional references in books hanging around the house, I have finished up with a real appreciation for what is still a developing field of research.

The 19th and early 20th century discoveries, although marked by enthusiasm and good intentions, were often problematic. Many did not think to consider the context within which objects were found, meaning that logboats were often divorced from any associated objects or structures. A failure to understand the likely outcome of removing logboats from their waterlogged environments led to fragmentation of the wood, and sometimes complete disintegration. Attempts at preservation were variable in their success rate, and some altered the wood so profoundly that later scientific techniques like radiocarbon dating could not be employed. Still, they are to be commended for their appreciation of what they found, and their attempts to preserve both the objects and, in various publications, the knowledge that they had of the objects.

The Carprow (Perth, Scotland) logboat, which dates to around 1000BC, showing the well-sculpted interior. Source: Perth Museum and Gallery

It is a common misconception that most logboats are prehistoric. The same basic manufacturing method, using a hollowed out tree trunk, gives the illusion of contemporaneity, but the similarities are misleading. Although many of the 19th and 20th century discoveries of logboats were simply assumed to be prehistoric, radiocarbon dating, and some dendrochronological determinations have indicated that most of them are more recent and prehistoric logboats are in fact rare. The small number of Cheshire examples were early and later Medieval, with only one lying in the realms of later prehistory. In other areas the date range can extend as late as the early 18th century, although these very recent examples are also uncommon. As a whole, the small number of prehistoric logboats do not provide a sufficient sample to lend themselves conveniently to statistical sampling, and this applies even to the somewhat larger of Anglo-Saxon and Medieval examples.

Possible catamaran-style arrangement of two logboats, suggested by researchers working on the Medieval River Conon logboat. Source: AOC Archaeology Group

Although they look the superficially same, the tools with which they were made and with which they were associated will have differed considerably over time, and no two boats were the same. Even during the Bronze Age at Must Farm, the designs changed and new features were added whilst others were discarded, demonstrating that over time there was no generic logboat, and each had its own shape, features and fittings. Whilst some of the underlying considerations will have remained the same from one century to the next, the skills and tools available will have moved on, and in some cases the underlying needs for logboats and how they were thought about will have been very different. Landscapes and population densities, economic opportunities, social hierarchies and belief systems will have born little resemblance from one period to the next, and it as well to remember that similarities in appearance of logboats disguise huge discrepancies of lived experience. This pull and push between similarities and differences over very long periods is part of what makes the logboat so interesting.

It is good to see a number of publications tackling some of the complexities head on, both for academic and public consumption. The excellent book and e-book The Poole Iron Age Logboat edited by Jessica Berry, David Parham and Catriona Appleby is, for example, a fine example of a publication dedicated to a single example, using all the data available to follow, where possible, the life history of the object from tree to discard.

Technological advances are helping studies. For example, improvements in lighting, laser scanning and new photographic techniques have enabled more accurate capture of surface details, which in turn is helping researchers to understand how different types of tools and techniques were employed in the making and maintenance of logboats, enabling past methodologies to be recreated.

Artist’s impression of the Carpow logbook under construction. Source: PerthshireCrieffStrathearn Local History..

New academic studies are beginning to move beyond the vital building blocks of logboats as typologies and tables of dates to build on this work and consider logboats as integral to both economic and social activity, involved in different levels of livelihood and experience. Looking at how logboats are built has emphasised the role of communities in securing the wood and forming it into the correct shape, creating a communal resource and a shared experience in the process. Some researchers have considered how log boats may be involved not only in everyday activities but as components of mobile livelihood patterns and cross-community contacts. Some researchers have considered logboats in terms of their role in ceremonial and funerary activities, demonstrating that the same themes involved in the humdrum of everyday life are woven into the more esoteric aspects of self-identity and awareness. Others are looking at the significance and social context of repairs or the types of decision and activity required in the final discard of a logboat. Each new thread of research contributes not only to what is known about logboats, but to what is known about the societies and communities that produced them.

Although many of these studies focus on prehistoric examples, there is no reason why the same questions and approaches should not be applied to early and later medieval examples. Instead of being isolated from their contemporary economic and social contexts as something exceptional that requires special explanation, logboats are being repositioned at the heart of our understanding of different periods of the past and the reasons why such boats may have continued to be so attractive. Although the Cheshire logboats represent only a small part of the jigsaw, each one is unique. Both as a group and as individual activists, they too have much to contribute to the overall picture.

TikTok video about the Baddiley logboat by Professor Howard Williams from the University of Chester.

Sources:

Books and papers

Berry, Jessica; Parham, David; and Appleby, Catrina 2019. The Poole Iron Age Logboat. Archaeopress Publishing

https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/33553/1/untitled.pdf

Bradley, Richard 2019 (2nd edition). The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press

Dincause, Dena F. 2000. Environmental Archaeology. Principles and Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Gregory, Niall 1997. Comparative study of Irish and Scottish logboats. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Edinburgh

https://www.academia.edu/66850719/Comparative_study_of_Irish_and_Scottish_logboats

Holtzman, Bob 2021. Logboat Repairs in Britain and Ireland: A New Typology. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, Vol.16, p.187–209

https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/447234/1/Logboat_Repairs_.pdf

Hurcombe, L.M. 2014. Perishable Material Culture in Prehistory. Investigating the Missing Majority. Routledge

Ingold, Tim 2013. Making. Anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. Routledge

Kröger, Lars 2018. Within the network of Fluvial ports. In: L. Werther / H. Müller / M. Foucher (ed.), European Harbour Data Repository, vol. 01 (Jena 2018)

Lanting, J.N. 1998. Dates for Origin and Diffusion of the European Logboat. Palaeohistoria 39/40 (1997/1998)

Lanting, J.N. and Brindley, Anna L. 1996. Irish Logboats and their European Context. Journal of Irish Archaeology 7, p.85 – 95

https://www.academia.edu/39510428/IRISH_LOGBOATS_AND_THEIR_EUROPEAN_CONTEXT

Latham, Frank A. 1991. Delamere. The History of a Cheshire Parish. Local History Group

https://www.themeister.co.uk/hindley/delamere_history_latham.pdf

Madeley, Charles 1894. On Two Ancient Boats, Found Near Warrington. The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol.46

https://www.hslc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/46-6-Madeley.pdf?fbclid=IwAR10_dKMr1to5_ctb-L9j9p2ah363YfsBnuwWRo4crO00hbwTssg8Tr_WSA

Matthews, K. J. 2001. I: The Iron Age of north-west England: a socio-economic model. Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, Vol.76, p.1-51

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/arch-2910-1/dissemination/pdf/JCAS_ns_076/JCAS_ns_076_001-052.pdf

McGrail, S. 1978. Logboats of England and Wales. National Maritime Museum Archaeological Series 2, British Archaeological Reports, British Series 51 (volumes I and ii), National Maritime Museum Archaeological Series 2. Archaeopress

McGrail, S. 2010. An introduction to logboats. In D. Strachan (ed) Carpow in Context. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, p.1-8.

Markoulaki Panagiota 2014. Depositional Practices in the Wetlands: The case of Prehistoric Logboats in England. Unpublished PhD Thesis, volume 1 (text). The University of Nottingham

https://www.academia.edu/34367806/Depositional_Practices_in_the_Wetlands_The_case_of_Prehistoric_Logboats_in_England

Morgan, Victoria and Paul 2004. Prehistoric Cheshire. Landmark Publishing

Mowat, Robert J.C. 1998. The Logboat in Scotland. Archaeonautica 14, 29-39

https://www.persee.fr/doc/nauti_0154-1854_1998_act_14_1_1183

Mowat, Robert J. C., Cowie; Trevor; Crone Anne and Cavers, Graeme 2015. A medieval logboat from the River Conon: towards an understanding of riverine transport in Highland Scotland

Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 145 (2015), p.307–340

Robinson, Gary. 2013. ‘A Sea of Small Boats’: places and practices on the prehistoric seascape of western Britain, Internet Archaeology 34

https://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue34/robinson_index.html

Sinclair Knight Merz 2004. Site Adjacent to Chester Road, Warrington, Cheshire. Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment. Oxford Archaeology North, August 2004.

https://eprints.oxfordarchaeology.com/4868/1/completereport.pdf

Switsur, Roy. Early English Boats. Radiocarbon, Vol.31, No. 3, 1989, p.1010-1018

https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/radiocarbon/article/download/1233/1238

Thompson, Anne, 2011. Arpley Landfill Site – Extension of Operational Life, Warrington, Cheshire. Archaeological Desk Based Assessment. February 2011

https://www.fccenvironment.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Appendix14.1_ArchaeologyDeskBasedAssessment.pdf

Watts, Ryan 2014. The Prometheus Project. EXARC Journal 2014/4

https://exarc.net/issue-2014-4/ea/prometheus-project

Websites

Heritage Gateway

Baddiley Mere oak logboat (Cheshire)

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=e780c761-f6c8-49fd-ae06-639d3f8ea7b0&resourceID=19191

Cholmondeley

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MCH5322&resourceID=1004

Delamere and Oakmere log boat

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=71202&resourceID=19191

Newbold Astbury

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=4bc4a8f2-2c5a-4934-baaa-754082364803&resourceID=19191

Warrington Logboat 1

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MCH8659&resourceID=1004

Warrington Logboat 2

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MCH8661&resourceID=1004

Warrington Logboat 4

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MCH8485&resourceID=1004

BBC News

Stanwick Lakes: Bronze Age log boat build reaches halfway point. 22nd October 2023, by Katy Prickett

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-northamptonshire-67055114

Stanwick Lakes: Volunteers replicate Bronze Age tools to build log boat

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-northamptonshire-65561744

Cheshire Archaeology News, Chester County Council

Issue 4, Spring 1997, p.2

http://www.cheshirearchaeology.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Spring_1997.pdf

Historic England

Ships and Boats: Prehistory to 1840. Introductions to Heritage Assets.

https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-ships-boats/heag132-ships-and-boats-prehistory-1840-iha/

Ships and Boats: Prehistory to Present. Selection Guide

https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/dsg-ships-boats/heag143-ships-and-boats-prehistory-to-present-sg/

Festival of Archaeology 2022

Warrington’s Spoon Shaped Dinghies

https://wmag.culturewarrington.org/2022/07/16/festival-of-archaeology-2022-warringtons-spoon-shaped-dinghies/

Academia

Beck, Lewis W. The Must Farm Logboats: Why Was Oak Used Primarily in the Construction of Logboats in Bronze Age Britain. Unpublished alumnus research, Cardiff University

https://www.academia.edu/32793784/The_Must_Farm_Logboats_Why_Was_Oak_Used_Primarily_in_the_Construction_of_Logboats_in_Bronze_Age_Britain

ScARF

The Carpow Logboat by Grace Woolmer-White and David Strachan

https://scarf.scot/regional/pkarf/perth-and-kinross-archaeological-research-framework-case-studies/the-carpow-log-boat/

Warrington Guardian

Your chance to see a piece of town’s history. 13th June 2002

https://www.warringtonguardian.co.uk/news/5267292.your-chance-to-see-a-piece-of-towns-history/

—–

Online references for some other logboats in Britain

In alphabetical order by site/boat name

Brigg, Hull

The Brigg Logboat

http://museumcollections.hullcc.gov.uk/collections/storydetail.php?irn=403&master=449

Carpow, Perthshire, c.1000BC

3,000 year old boat one of the first objects to enter the new Perth Museum after unique conservation treatment. Thursday 12th October 2023

https://perthmuseum.co.uk/3000-year-old-boat-one-of-the-first-objects-to-enter-the-new-perth-museum-after-unique-conservation-treatment/

Recording, conservation and display: Episodes in the continuing life of a 3,000-year-old logboat from the River Tay

https://www.digitscotland.com/recording-conservation-and-display-episodes-in-the-continuing-life-of-a-3000-year-old-logboat-from-the-river-tay/

The Carpow Logboat

https://scarf.scot/regional/pkarf/perth-and-kinross-archaeological-research-framework-case-studies/the-carpow-log-boat/

Conon logboat

Lost & Found: the River Conon Logboat. A Medieval logboat from the River Conon near Dingwall, Highland

https://www.aocarchaeology.com/key-projects/river-conon-logboat

Ferriby Yorkshire log boats

http://www.ferribyboats.co.uk/discoveries.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferriby_Boats

Giggleswick Tarn, North Yorkshire

New voyage of discovery for museum’s medieval vessel

https://news.leeds.gov.uk/news/new-voyage-of-discovery-for-museums-medieval-vessel

Hanson, Derbyshire

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/hanson-log-boat

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanson_Log_Boat

Hasholme logboat

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasholme_Logboat

Lurgan canoe

The Lurgan Canoe, an Early Bronze Age boat from Galway. Irish Archaeology, 21st October 2014.

http://irisharchaeology.ie/2014/10/the-lurgan-canoe-an-early-bronze-age-boat-from-galway/

Murston Marshes log boat

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=419871&resourceID=19191

Poole

The Poole Iron Age Long Boat (e-Book):

https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/33553/1/untitled.pdf

Mystery boat carved from massive tree trunk

https://www.wessexmuseums.org.uk/collections-showcase/iron-age-logboat/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poole_Logboat

Shardlow, Derbyshire

https://www.derbymuseumsfromhome.com/dm-object-highlights/a-bronze-age-logboat

Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland

The Neolithic log boat at Strangford Lough

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/northern-ireland/strangford-lough/history-of-strangford-lough