Many, many thanks to Paul Woods (Chester Green Badge Guide who leads the cemetery tour Stories in Stone) for sending me the scans of this leaflet by Cheshire RIGS and the Northwest Geodiversity Partnership, apparently published in 2012. It looks at the most common types of stone used, gives some geological details about it, and discusses how some of it responds to environmental conditions. I’ve shared the JPEGs below but I have also turned it into a PDF that you can download by clicking here. I cannot wait to take it for a test drive!

Author Archives: Andie

Overleigh Cemetery, Chester #2 – The living, the dead and the visitor

In part 1 of this series on Overleigh Cemetery the economic background to Overleigh Old Cemetery was introduced briefly, and details of the reasons and execution of the foundation of Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries were discussed. Here, in part 2, both Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries are explored in a little more depth. There are a great many components that contribute to how a gravestone looks, what it says, and what it meant to the bereaved. Between the sculptural forms, the symbols used on headstones and the inscriptions, as well as the design of the the cemetery itself and the ways in which it evolved and was used and perceived at different times in the past, Overleigh has a lot to contribute to how we think about Chester and its occupants.

In part 1 of this series on Overleigh Cemetery the economic background to Overleigh Old Cemetery was introduced briefly, and details of the reasons and execution of the foundation of Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries were discussed. Here, in part 2, both Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries are explored in a little more depth. There are a great many components that contribute to how a gravestone looks, what it says, and what it meant to the bereaved. Between the sculptural forms, the symbols used on headstones and the inscriptions, as well as the design of the the cemetery itself and the ways in which it evolved and was used and perceived at different times in the past, Overleigh has a lot to contribute to how we think about Chester and its occupants.

Eliza Margaret Wall, died 1899, aged 30. Other family members were added in future years up to 1936

As a starting point, it is useful to look at who the main users of the cemetery were and are, both living and deceased, before moving on to a general guide to what to look out for if you are a visitor interested in learning about what the cemetery has to offer.

- Part 1: Introduction to the background and the establishment of Overleigh Cemetery

- Part 2: The living, the dead and the visitor at Overleigh

- Part 3: Shifting ideas – the move away from monumental cemeteries towards cremations and lawn cemeteries

- Part 4: The research potential of cemeteries; and Overleigh case studies

- Part 5: The Overleigh Old and New Cemetery today and in the future

- References for all five parts are here

As in part 1, where I have included a photograph of a grave and there is information about it on the Find A Grave website, I have added a link. For anyone using the database for their own investigations, note that Find A Grave treats Overleigh Old and New cemeteries as two different entities and you have to search under the correct one.

I have stuffed this full of photographs to help explain some of my points, so Part 2 looks bigger than it actually is. You can click on any of the images to see a bigger version.

With many thanks again to Christine Kemp (Friends of Overleigh Cemetery) for her much-appreciated ongoing help.

====

People

Graves represent people, the living and the dead, both entangled in the complexities of funerary rites.

The bereaved

A funeral at Overleigh Old Cemetery. Detail of 19th century engraving of Overleigh Cemetery. Source: Wikipedia

Although this post is about a burial ground and its graves, funerary traditions and practices are all as much, if not infinitely more, about the living. The need to recognize and commemorate loss, not merely at the funeral but prior to it and after it are essential to people, even today when the traumas associated with death tend to be handled in more internalized ways than in the pre-war periods.

Gravestone of Geoffrey Mascie Taylor, died 1879. If anyone has any idea what the symbol represents at the top of the gravestone, please let me know.

During the Victorian period there was an elaborate process of marking a death, a tradition of precise convention and ritual, expressed both within the family and communally. When someone dies the living are left behind to handle a loss as best they can, and cemeteries and memorials are only one one part of that process. The end to end process from death to mourning is all a part of the Victorian experience of bereavement. Visiting and tending the grave, bringing flowers for the deceased, was part of this process, in which women had a key role, and demonstrating bereavement in public essentially brought the grave into the domestic sphere. Several of the books listed in the references, go into some detail about the Victorian expressions of mourning, and books by James Stevens Curl in 1972 and Judith Flanders in her recent overview provide great insights, but if you want a much shorter book with a still very comprehensive and well written overview, Helen Frisby’s Traditions of Death and Burial offers an excellent overview of Victorian and later bereavement ceremonies.

John Owens JP, died 1853, age 72. “A Merciful Man Whose /

Righteousness Shall / Not Be Forgotten.” There are no additional inscriptions on this impressive headstone

In the Victorian period it has been argued that the lead-up to a funeral, the funeral itself and its aftermath were all components of an intention to promote social status, wealth and the knowledge of and participation in deeply embedded social conventions that specified in detail how death should be handled and how mourning should take place. The Industrial Revolution had created a new type of middle class, many of whom were making livings based on manufacturing and commerce, as well as roles in the growing legal, medical, administrative, banking, and similar sectors. Even though there were more opportunities for social mobility, and the ability for individuals to define themselves in new terms, the aristocracy still provided a model for those with social ambitions. Conspicuous displays of personal and family identity and wealth had become fundamentally important in this need to establish a dignified and self-important identity at a location between the upper and working classes. It was also important for the lower middle classes to distinguish themselves from those who were less financially robust, doing what was perceived as more menial work, defining themselves as socially distinct from the working class. Hierarchy, with all its subtleties during the Victorian period, was important, deeply-felt, and complex, and much of this is reflected in funerary rituals.

More recently it has also been recognized that elaborate Victorian and early Edwardian funerary ceremonies were not merely social devices but reflected the great trauma associated with loss in a world where medicine was in its infancy and where where the middle class was defining itself within often smaller families than previously. Sickness and death could be both frequent by comparison to today, and was often profoundly distressing. At the same time, sanitation and health were slowly improving in the second half of the century, meaning that once childbirth and infancy had been survived, people physically lasted longer than they had done in the past, building relationships but more frequently succumbing to old-age problems, becoming invalids who were cared for within the home. National and community diseases were frequent, some of them long-lasting, and the role of women in nursing their relatives became increasingly important where professional standards of nursing were, just as much as the professionalization of medicine, in their earliest incarnation. Middle class family ties, and the Victorian and Edwardian sense of moral responsibility to relatives, ensured that sickness was a very frequent component of family life.

More recently it has also been recognized that elaborate Victorian and early Edwardian funerary ceremonies were not merely social devices but reflected the great trauma associated with loss in a world where medicine was in its infancy and where where the middle class was defining itself within often smaller families than previously. Sickness and death could be both frequent by comparison to today, and was often profoundly distressing. At the same time, sanitation and health were slowly improving in the second half of the century, meaning that once childbirth and infancy had been survived, people physically lasted longer than they had done in the past, building relationships but more frequently succumbing to old-age problems, becoming invalids who were cared for within the home. National and community diseases were frequent, some of them long-lasting, and the role of women in nursing their relatives became increasingly important where professional standards of nursing were, just as much as the professionalization of medicine, in their earliest incarnation. Middle class family ties, and the Victorian and Edwardian sense of moral responsibility to relatives, ensured that sickness was a very frequent component of family life.

TThe monumental grave shrine of Henry Raikes, died 1854, aged 72, Chancellor of the Chester Diocese and one of the founders of the Chester “Ragged Schools.” Overleigh Old Cemetery..

Relatively recent research has also suggested that working class people felt no less strongly about the loss of their partners, siblings and children. Many working class families were crowded into insanitary areas all over in Britain, and notable areas have been identified in Chester, forcing people into much closer proximity, and this promoted the transmission of sickness and disease with a consequent cost in terms of poor health. Sickness was handled within families, which caused many problems in household management, where women frequently worked for a living, often in domestic capacities. This resulted in the occasional recourse to a new breed of hospitals as well as a frequently dubious type of pre-professional paid nursing care. The ease of disease transmission meant that those living so close together and in such insanitary conditions were most at risk of epidemics, and the mortality rate was much higher than in middle class households. There were clubs into which people could pay a subscription to save up for funerals, just as there were clubs to save up for Christmas, and there are several pauper graves at Overleigh. But for some the costs were too high, so many graves were unmarked, and the grief of some families was never recorded meaning that these losses are not captured.

The monument for Joseph Randles, died 1917, aged 65-66. Note the partially veiled urn, which will be mentioned later.

It is easy to forget that until the NHS was established in 1948, most people still died at home rather than in hospitals, hospices or nursing homes, and that families housed the deceased, until burial, within their homes, and those deceased, laid out in front parlours in their coffins, were visited by friends and families. The introduction of the funerary Chapel of Rest in the later Victorian period helped to reduce the time when the deceased remained in the house, but it was still a common part of a death that the dead remained amongst the living until the funeral well into the 20th century.

The focus on ceremony and ritual altered over time, with a considerable change of direction from the elaborate ceremonies of the Victorians to the minimalist approaches taken today. This does not mean a growth of indifference to death, but it does indicate changes within society. The beginnings of this are to be found in the Edwardian period, particularly during and after the First World War, when the nation’s horses that traditionally pulled hearses were required for the war effort. Funerals became even less demonstrative after World War 2. This will be discussed a little more in Part 3.

On this Armstrong family cenotaph and headstone in the Overleigh New Cemetery, three sons predeceased their parents aged 32 in 1917, 22 in 1918, and 39 in 1927, the first two of them at war, all of which must have been a shocking loss. Their parents are commemorated here too.

In the cemetery itself, the most obvious incorporation of gravestones into the world of the living is the highly visible custom of flowers and other gifts having been left in front of a headstone. Fresh flowers in particular give the sense of a grave being regularly tended but artificial flowers and other items also serve to mark the continued attention to a grave by those who wish to indicate their recognition and care. My father, who was born in 1936 and grew up on the Wirral, says that when he was a small boy he was taken regularly to the graves of his relatives in Liverpool, where there was a flower shop outside the gates, and flowers were purchased, a visit was made to family graves, and a picnic was enjoyed nearby. It was a visit of celebration, continuity and memory, a positive occasion.

The other most obvious indication of a gravestone continuing to have a role is the presence of multiple inscriptions on many memorials, as individual family members are lost and the living are compelled to update the inscriptions. Many of these gravestones capture this passage of time and accumulated loss very effectively, telling long narratives of family loss, sometimes covering several decades, and suggesting multi-generational involvement with funerary activities and commemoration, the sense of a continuum between the past, the present and the potential future.

The Deceased

The deceased may seem to be passive and inanimate, but they have voices in at least three ways. First, they may have had input into their own graves, including its location, its design and its use as a single plot or a family plot. In this sense they are very much agents of their own burials. Second, the very process of memorialization, whether by family or friends, gives the departed an enduring presence that lasts into the modern world, a very material presence. Some of those who died may also have obituaries to be found in newspaper archives, and accounts of inquests into their deaths, filling out a much richer picture of former lives, and those who were in positions of influence will have had much more information captured in official documents and even preserved journals. In this way they can contribute very significantly to modern research projects, as much as that may have surprised them. Third, they occupy the living landscape of cemeteries, spaces that occupy often new places in modern life and that are valued today. At Overleigh I have seen people walking from one end to the other pause to read an inscription, and dog walkers wandering around, pausing to take note of a particular grave. The dead area still amongst the living, even when they are not even slightly connected today with their ancestors. Those who care for their graves, and tours that bring visitors, all do their essential bit to keep the deceased amongst the living.

The deceased may seem to be passive and inanimate, but they have voices in at least three ways. First, they may have had input into their own graves, including its location, its design and its use as a single plot or a family plot. In this sense they are very much agents of their own burials. Second, the very process of memorialization, whether by family or friends, gives the departed an enduring presence that lasts into the modern world, a very material presence. Some of those who died may also have obituaries to be found in newspaper archives, and accounts of inquests into their deaths, filling out a much richer picture of former lives, and those who were in positions of influence will have had much more information captured in official documents and even preserved journals. In this way they can contribute very significantly to modern research projects, as much as that may have surprised them. Third, they occupy the living landscape of cemeteries, spaces that occupy often new places in modern life and that are valued today. At Overleigh I have seen people walking from one end to the other pause to read an inscription, and dog walkers wandering around, pausing to take note of a particular grave. The dead area still amongst the living, even when they are not even slightly connected today with their ancestors. Those who care for their graves, and tours that bring visitors, all do their essential bit to keep the deceased amongst the living.

Art Deco style headstone of Ralph Esplin, died 1935, aged 67

It has been the experience of cemeteries since the beginning of the 17th century in Britain that graves are tended for perhaps three generations after which they fall out of use, as families move away or simply move on. Genealogy makes some of them briefly relevant, but the funerary landscape is a strange mixture of the abandoned and the perpetuated. Local authorities and Friends societies contribute to the task of caring for abandoned graves, but this is a very different relationship from those that are still visited by family members. In Victorian cemeteries, there is always a rather strange dynamic between the historical sections and those that are still the essence of loss, bereavement and and ongoing engagement.

The deceased in the early periods of the cemetery capture something of Chester’s evolving social, economic and cultural endeavors, as it attempted to secure its future and create a stable and prosperous community. Those who are represented in the cemetery are largely those who were either already successful in establishing themselves within this community or were making the attempt to improve themselves and gain status; the unmarked pauper and cholera graves are amongst the hidden histories of Overleigh and of Chester itself. There is time-depth here too, as we can track changes from 1848, when the Old cemetery was established, through the Edwardian period and both World Wars, and the changes during the post-war period up until the present day. I have been learning how much work it takes to see beyond the sea of graves and to read history captured in the cemetery landscape and monuments, and it is all there to be found, the world of the dead contributing to an understanding of the transforming past and how society’s views on death and commemoration changed. Parts 3 and 4 will go into this in more detail.

===

Visiting Overleigh for the first time – what to look out for

The central monument, in rose granite, is a truncated obelisk, indicating a life cut short and usually associated with the loss of younger people, although not invariably. In this case, Harry MacCabe who died aged 26.

I have started here with the most obvious way of getting to grips with a cemetery – how things look when you walk through for the first time. This is about shapes, materials and the visual cues that you can pick up at first glance to give an indication of what the casual visitor may want to focus on during a first visit.

The majority of monuments at Overleigh are vertical, unlike the variety seen in local churchyards that include a variety of other horizontal and chest-type forms, as discussed in connection with the churchyard at Gresford, some 10 miles south of Chester. The example below shows one of the horizontal representations, which are less numerous, although of course by being less visible are more likely to be overlooked.

Although I discuss Overleigh as a site that helps us to connect with history, it is important to remember that both Old and New parts of Overleigh are still in use for new interments and cremation memorials, and that families and friends are still regular visitors to visit their departed and tend their plots. All visits by those of us who are not connected with family or friends interred in the cemetery need to explore with respect and care for those other visitors who are at the cemetery for the purpose of connecting with the departed.

The horizontal gravestone of Major Richard Cecil Davies is one of the relatively few gravestones that are not vertical. Some, of course, have fallen over and are now just as horizontal as this one, but this was always intended to lie over the grave and face upwards. These are always vulnerable to being taken over by grass and weeds, and need an eye kept on them.

Themes and symbols

Author James Curl (1975) found this advert in an 1860s guide to Highgate Cemetery in London, showing a range of grave monuments available for purchase. Most of these have equivalents at Overleigh.

How were headstones and monuments chosen? From the 1830s onward stonemasons had catalogues from which headstones could be chosen, just as there are today. Today there are also catalogues from which to choose, many of them online and offering a wide range of alternatives. At the same time, some families might prefer a grave that is similar to that of other family members, and some might want to emulate styles admired in a local cemetery. The imagery on the graves during the Victorian and Edwardian periods formed a rich language of meaning that is understood by all, including the illiterate. Sometimes the imagery used on a gravestone may say as much if not more about the emotional relationship between the living and the deceased than the text inscription, including the hopes that the living had for their dearly departed.

When you are walking around, you will notice that certain themes are recurring in the designs of the gravestones in both halves of the cemetery. These represent specific choices that people have made and the ideas that they wish to communicate. These can either be sculptural memorials or more modest headstones that incorporate carved imagery. Sometimes headstones just include text, and sometimes there is just a kerb with no headstone which usually lacks imagery, but the symbolic medium is often an important part of the message that a gravestone communicates, imparting a different type of information from the text, often rather more subtle and conceptual than what is written, sometimes capturing emotions and ideas rather more effectively than words. There is a usually a minimalist formality in what is written, but this does not extend to imagery and symbols, which can be far more expressive. The themes and symbols mentioned below are just examples that I have found in Overleigh Cemetery.

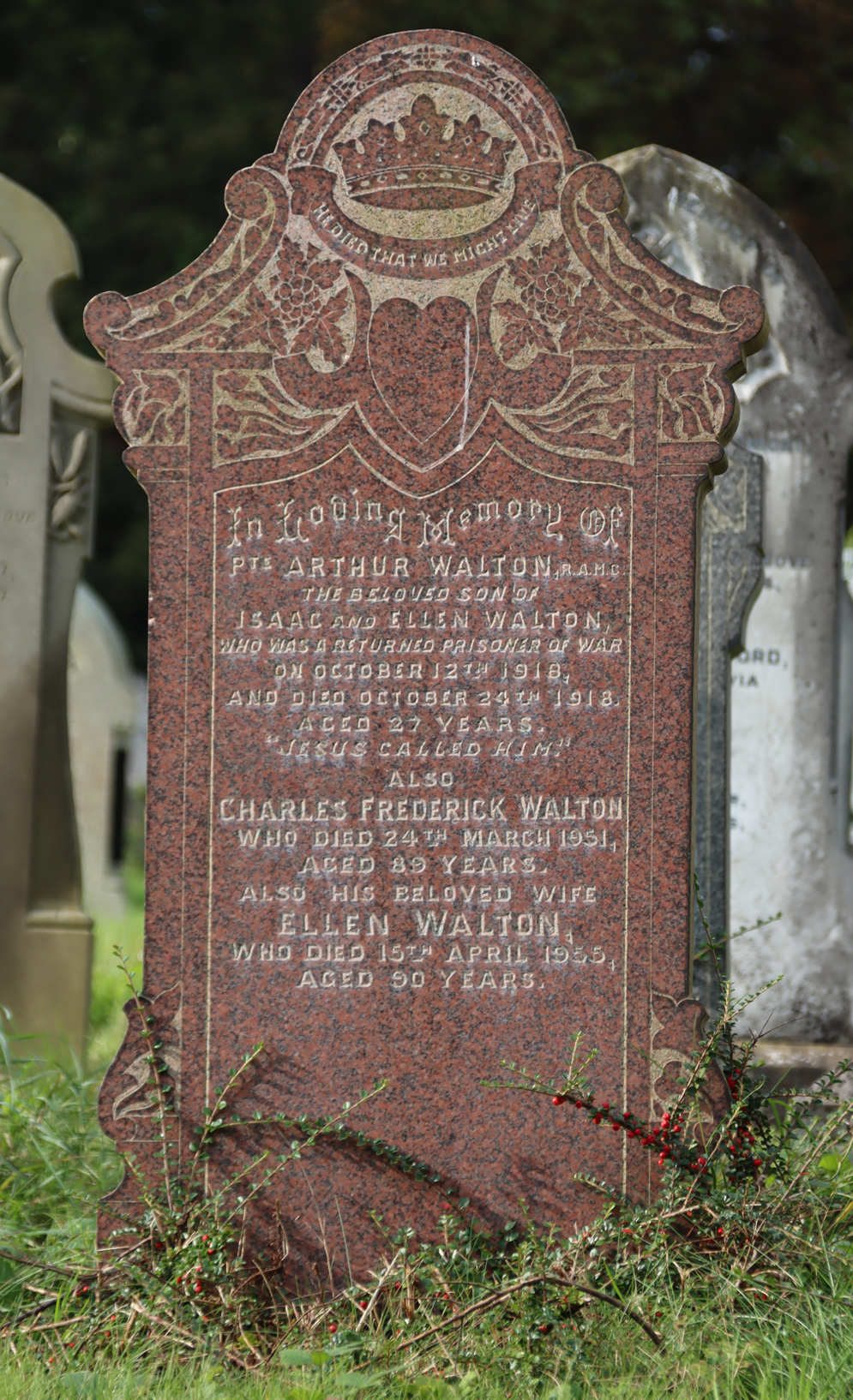

The memorial to Private Arthur Walton, died 1918 aged 27.

In the memorial to Private Arthur Walton shown left, the overall language of the iconography, seems to reflect the concepts of Christianity and the life of Jesus in response to the loss of a much-loved son in the First World War. The crown can symbolize victory but is also the emblem of Jesus and Christian immortality. Beneath it, the Biblical quote “He died that we might live” refers to Jesus, but might also refer to the sacrifice of Arthur Walton himself. The heart is a symbol of everlasting love of Christ and also of the charity espoused by St Paul, but also captures personal love. The grapes and vine-leaves are usually related to themes connected with Jesus including the blood of Christ, the Last Supper and the Holy Sacrament. Overall the iconography of the grave is probably one of personal sacrifice and its association with Christian values and the sacrifice of Christ himself, whilst at the same time demonstrating very deep personal loss. As well as being very moving, this is a good example of how the imagery can contribute to the overall narrative of a headstone or memorial.

Hester Ann Clemence, died 1914, aged 62, with other members of the family commemorated on the pedestal steps beneath the floral Celtic style cross. The steps often represent the steps representing Christ’s climb to Calvary. All of the creativity and suggestion of emotion in the monument is in the design; the inscription is minimalist. Although the encircled cross was originally associated with Irish graves, it became popular throughout Britain during the 19th century.

Of the overtly Christian-themed grave markers the dominant shapes are the crosses that re-appear for the first time since the Reformation during the 19th century, symbols both of Christ’s sacrifice and of resurrection, and proliferate at Overleigh, from the very simple to the seriously elaborate. Crosses carved with decorated themes are widespread through the cemetery. Although there had been very few crosses before the Victorian period, due to fear of association with papism. A popular choice at Overleigh was the so-called Celtic cross, with Celtic-style designs covering the surface. A popular variant has the top of the cross contained within a stone circle. Although originally associated with Irish and Scottish graves, after 1890s in particular, when a Celtic cross was chosen by the celebrated art critic John Ruskin for his own memorial in Coniston, it became popular for burials of all religious persuasion. A cross on a set of steps is often intended to represent the steps the Christ climbed to Calvary, but they might also simply be chosen for their monumental impact. Flowers on a cross are indicative of immortality. There are quite a few angels, messengers of God and the guardians of the dead who also transport the soul to heaven. The letters IHS often occur on graves in both urban and rural cemeteries and represent a Christogram, the three letters of the name of Jesus in Greek (iota, eta, sigma).

The truncated obelisk erected in memory of Francis Aylmer Frost. This photograph was taken by Christine Kemp when this area was not the overgrown jungle that it is now (you can see another photograph of this column, as it is today just below. Copyright Christine Kemp.

Many emblems are appropriated from earlier periods. Pagan themes include the many Egyptian-style obelisks (more about which you can read on my post about the Barnston memorial in Farndon). A splendid fluted truncated Doric column, a not uncommon cemetery icon but in this particular case perhaps a nod to Chester’s Roman past, is located just inside the River Lane gate to the Old Cemetery, its truncation indicating a life cut short, and generally indicating someone who died young, although in this case Francis Aylmer Frost was 68; another truncated column was dedicated to Harry MacCabe who was 26. It is not the only one in the Old and New cemeteries, but it is by far the most impressive, shown at far left in the image below. Its base is so badly overgrown with viciously thorny brambles that I couldn’t begin to find an engraving without losing half my hands and arms, and so remain ignorant as to who it commemorated. I need some garden shears next time!

Floral themes on the grave of Thomas George Crocombe, died 1913 aged 20, the eldest of 9 children. Overleigh Old Cemetery.

Flowers are a popular carved theme on headstones. Some have specific associations, such as the lily, standing for purity and a return to innocence; the rose, which indicates love (different coloured roses mean slightly different things), lilies of the valley, with connotations of innocence and renewal; daffodils that, flowering in spring, represent rebirth; and daisies, which symbolize innocence and were a popular choice for child graves. A sprig of wheat often indicated someone who had lived to a good age. Ivy, ironically, is representative of life everlasting and due to its enduring character. It is often show winding its way around cross headstones; today rampant ivy is one of the greatest causes of damage to graves in cemeteries and churchyards. The most popular of birds shown on graves were doves, symbolizing either the Holy Spirit guiding the deceased to heaven, or general values of spirituality, hope and peace. There are several at Overleigh.

Detail of the headstone of Harriett Garner and other family members with clasped hand motif. in this case it perhaps suggests father and daughter. Harriett’s father, who gave evidence at the inquest into her suicide, was certainly very distressed by the loss of his daughter. They are usually quite common in cemeteries, I have noticed only a few at Overleigh.

An urn is a very well represented motif, quite often topping a headstone as a sculptural component, and indicating the soul of the deceased; when draped with a veil they may indicate the soul departing or represent grief of mourners. Angels are popular sculptural elements at Overleigh, indicating the soul of the deceased being accompanied to heaven. Much less frequently shown than angels, but popular in many cemeteries, are images is that of a weeping woman, representing the loss of a person and the mourning of the bereaved. Small statues of children often indicate the grave of a young child. Clasped hands, common at some cemeteries but apparently not as well represented at Overleigh, indicate unity and may suggest the bonds of husband and wife, or of friendship or the hope to be reunited with loved ones; some have been carved to show the clothing and character of the hands as distinctly male or female. An anchor may show that the deceased was professionally connected with the sea, but may also represent hope; a variation is the anchor with a woman, the embodiment of hope, although I have not seen an example of the latter at Overleigh. Books may have many meanings – sometimes they are associated with the Bible of the clergy or the work of scholars, whilst others may mean knowledge or wisdom, or may simply represent chapters in life.

On the left, the headstone of Arthur Davies. The text wrapped around the anchor reads “Hope is the Anchor of the Soul.” The inscription contains other commemorations. The headstone of Florence Taylor Battersby and other family members in the middle, topped with a dove. The grave at far right shows the Christogram IHS, an abbreviation of the name of Jesus in Greek and Latin. Click to enlarge

===

The child grave of Violet Patterson, died 1929, as well as other members of her family, one of whom, Edward Andrew Patterson, who died and was cremated in 2007, is inscribed on one page of the book. This is one of the longer enduring of the graves at Overleigh, in use for 78 years.

A book included on a gravestone may indicate any of a number of ideas. Prosaically, the grave’s owner might be involved in the printing, publishing or book-selling trades. Alternatively they might be a scholar or, if the book is intended to be a Bible, a cleric or someone particularly devout. In cemeteries one side of an open book often has the name of the husband or wife, whilst the other side remains blank until the other partner has also died, when the blank page can be completed. Sometimes the blank page is left incomplete, possibly because the former partner has remarried or moved out of the area, or has left no provision for the disposal of his or her remains.

There are also more modern emblems and themes that people have incorporated into grave carvings. In the Overleigh New Cemetery in particular there are Art Deco, Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau themes. Although often contained within crosses, the Art Nouveau decorations seem otherwise celebratory of life. The combination of Christian crosses with modern themes perhaps positions religion within a modern context where there is no need to refer back to much older historical values in order legitimize Christian beliefs. One of them, dedicated to Anna Maria Meredith, has a Biblical quote on it (fourth from the left, a most unusual headstone, although there is a second example in the cemetery). The memorial to Frederick Coplestone, third from left, shows St Francis of Assisi. It will be discussed further in Part 4.

Memorial in the cremation Garden of Reflection showing a locomotive. Roy Douggie, died 2010 aged 77, and his wife Beryl, died 2016, aged 79. That sycamore is going to need weeding out if it is not going to do permanent damage!

As can be seen on more modern gravestones and memorials, most of which can be seen in the Garden of Reflection in Overleigh Old Cemetery and at the very far end of Overleigh New Cemetery and even more dramatically at the post-war cemetery at Blacon, gravestone types and materials have become standardized, and the rich visual language of symbols and icons employed became much less varied over time, and are now often eliminated entirely, although secular themes are sometimes chosen instead. In modern cemeteries, regulations about the nature of grave markers limit potential for developing new monumental statements, but the decline in religious involvement in everyday life is also a part of this trend. The language of religious imagery to convey complex values (semiotics) now takes a back seat, even where commemoration is required, with modern secular images often chosen instead of Christian ones. There are exceptions, and Roman Catholic memorials can still be quite elaborate. Today modern gravestones and memorials can be less about choosing the perfect message for eternity than creating an appropriate personal message and style for the here and now, which is an attractive feature of many modern memorials.

====

There are many more symbols and themes on gravestones than those covered in my brief overview above, some quite common at cemeteries, some unique, and it is worth looking out for some interesting examples.

===

Inscriptions

Alice Maud Gwynne, died 1921 at the age of 42 which bears the inscription “There’s no pain in the homeland,” the monument topped with an urn

Inscriptions can be presented using various different fonts, sizes and colours all on the same monument, which creates a sense of texture. Inscriptions are often filled with colour to make the text stand out from the background stone and make it easier to read. Lead lettering was occasionally inset into stone to achieve the same impact. The different styles of text create a great deal of variety in the visual impact of the cemetery.

Headstones in Overleigh tend to be fairly minimalist in terms of the information they provide, many simply naming family members and providing a date of birth and death, perhaps a note about the role of the deceased, particularly where this was a high status position. Most contain some sort of affectionate phrase or such as “In loving memory of,” “in affectionate remembrance of,” “beloved wife,” “dear husband,” etc. Others may contain a little more information. Some may state the town or village name of the village, or even the property, where the deceased was resident.

The commemoration to 9 year old Walter Crocombe, his mother Sarah, 68, her husband George, 88, and their 4 year old grandson Eric.

Multiple dedications following the initial interment help to give a sense of the family context of both the first and and subsequent family members, and the longer they were in use, the more resonance they had for the family as successive generations interacted with the monument not merely to a single person but to a family commitment and tradition. The child grave of Violet Patterson, died 1929, includes dedications to other members of her family, and was in use for 78 years, with the latest inscription dedicated to a family member who died and was cremated in 2007.

Only war graves tend to give details of how death happened, such as “killed in action” or “killed in flying accident,” although there are never any details. A great many refer to the deceased having fallen asleep, a euphemism for having died that skirts around and sometimes deliberately disguises how the death occurred. Occasionally a grave will refer to the suffering of an individual, although I have seen fewer at Overleigh than in churchyards. The commemoration of Sarah Crocombe at Overleigh reads “Her pain was great / She murmured not / But hung on to / Our Saviour’s cross.” The monument to Alice Maud Gwynne comments “There’s no pain in the homeland,” which implies that she may have experienced some suffering towards the end of her life.

The memorial to Josephine Enid Whitlow in Overleigh New Cemetery (thanks Chris!) who died in 1938.

For obvious reasons, child graves can be more expressive than others about personal feelings of grief and loss. The grave of 2-3 year old Josephine Enid Whitlow in Overleigh New Cemetery, for example, shown towards the top of this post, has a statue of a small child labled “JOSIE” (Josephine Enid Whitlow) accompanied by the the inscription “Jesus Walked Down The Path One Day / And Glanced At Josie On His Way / Come With Me He Softly Said / And On His Bosom Laid Her Head.” She died in an isolation hospital in 1938. The grave of the Crocombe family shown above records the loss of 9 year old Walter: “Little Walter was our darling / Pride of all the hearts at home / But the breezes floating lightly / Came and whispered Walter come.”

A few graves have Latin inscriptions. Latin is often used on Roman Catholic graves, and the letters RIP often indicate a Catholic grave, standing for the words “requiescat in pace,” meaning “rest in peace”, part of a prayer for the dead. A nice little gravestone commemorating Thomas Hutchins, near the entrance on Overleigh Road has the legend “stabat mater dolorosa” inscribed along the line of the arch, meaning “the sorrowful mother was standing,” a reference to the Virgin Mary’s vigil during the crucifixion. It is one of a number that ask the reader to pray for the soul of the deceased.

The small, relatively isolated gravestone of Thomas Hutchins, died 1879, aged 39–40

Perhaps the most minimalist of all the inscriptions, in terms of information imparted, is this curious woodland-style headstone topped with a downward-facing dove, shown below: “With Sweet Thoughts of Phyllis from Mother and Father and Aubrey.” Given the lack of any useful information it is not surprising that there is no information on the entry for it on the Find A Grave website, but the headstone has charm, and the lack of data is really intriguing, because this was not an inexpensive monument. Chris tells me that her last name was Elias. There must have been a story here, but how to find it would need some extensive research that would require access to the original stonemason’s records.

“With Sweet Thoughts of Phyllis from Mother and Father and Aubrey,” Overleigh New Cemetery

Although it might be expected that headstones would give a wealth of information, this is rarely the case at Overleigh, although names, dates of birth and death and place names are a good place to begin with additional research.

There are several books and websites that list some of the most common cemetery themes and symbols, which are very helpful for decoding some gravestones and memorials.

===

Visually personalized headstones

Memorial to Richard Price, Dee salmon fisher, who died in 1960 aged 59. Overleigh Old Cemetery

Personally commissioned scenes, where they are shown, are very specific. One of the most evocative is the gravestone that has a white marble section showing the Grosvenor Bridge, flanking trees on the river banks and a solitary, empty rowing boat moored in the middle of the river. It is dedicated to Richard Price, salmon fisherman, who died in 1960 aged 59. Salmon fishing on the Dee has its own history, well worth exploring, and Richard Price was one of the last to make a living from it. With Art Deco style wings either side, and an urn within the kerb, which could have been added at any time but appears to be in the same stone as the rest of the monument, it is an attractive and very personal dedication, becoming a little overgrown. Richard’s wife Rose, who died in 1987 aged 81, is also commemorated on the stone.

One of the more startling graves when seen from a distance, but completely charming and evocative when seen up close, is the full-colour section of a headstone to Vincent John Hedley, with a scene showing a fly-fisherman in a river or estuary with a rural scene, a rustic bridge, flying geese, an evergreen woodland, a bare hillside and a sunset or sunrise. It seems probable that Vincent John Hedley was a keen fly fisherman.

Vincent John Hedley, died 1997, aged 70. Overleigh Old Cemetery

Small section of an elaborate grave to Annie Myfanwy Roberts, died 1986, aged 73-74, showing photographs of family members.

A very well-tended grave in Overleigh New Cemetery is extremely monumental in its scope and intention, and includes photographs of the deceased, far more elaborate than the Anglican tradition but in keeping with the idea of the personalized scenes above that include visual as well as textual references to the personal. Whereas the two headstones above show evocative and nuanced scenes that suggest how lives were lived, the photographs of lost people show nothing of the lives that the people lived but are instant reminders of the faces of the departed, instantly emotive for the living, indicating a different way of thinking about and representing those who have been lost and are grieved for.

Materials

Although the most obvious thing about a grave is its shape, together with its ornamental elements, the choice of materials is also an essential part of the design of a monument, and helps to determine its appearance. As Historic England pointed out in their report Paradise Preserved, “the rich variety of stone within cemeteries represents a valued resource for the understanding and appreciation of geology.” The good news is that in 2012 Cheshire RIGS and the Northwest Geodiversity Partnership produced a five-page leaflet, Walking Through the Past: Overleigh Cemetery Geodiversity that describes some of the geological background to stone types used on gravestones at Overleigh Old Cemetery, which you can download as a PDF by clicking here.

Although the most obvious thing about a grave is its shape, together with its ornamental elements, the choice of materials is also an essential part of the design of a monument, and helps to determine its appearance. As Historic England pointed out in their report Paradise Preserved, “the rich variety of stone within cemeteries represents a valued resource for the understanding and appreciation of geology.” The good news is that in 2012 Cheshire RIGS and the Northwest Geodiversity Partnership produced a five-page leaflet, Walking Through the Past: Overleigh Cemetery Geodiversity that describes some of the geological background to stone types used on gravestones at Overleigh Old Cemetery, which you can download as a PDF by clicking here.

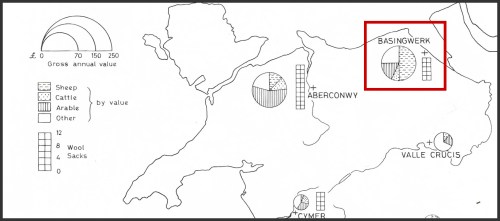

Local red sandstone was a popular choice, the same material used to build Chester Cathedral. Yellow sandstone, presumably much of which came from the Cefn quarries in northeast Wales, is finer-grained and often easier to sculpt, but is very vulnerable to pollution and, as a result, de-lamination. Pale limestone and granite are available from British sources, and are scattered throughout the cemetery. Limestone is a sedimentary stone like the sandstones, and relatively soft and easy to sculpt, whereas granite is an igneous rock, very hard and enduring, often with a very attractive flecked texture, but far more difficult to shape. Imports from overseas include marble and various exotic granites, which are higher-status materials with smooth surfaces that lend themselves well to sculptural memorials. Rose granite, so beloved of the ancient Egyptians, is well represented, usually polished to a high gloss. The majority of modern headstones are in highly polished black granite. Local schools would probably welcome a geology trail through the cemetery.

Cross made of a composite of two different materials, with pieces of stone inserted rather coarsely into what looks like concrete and was probably a low-cost solution to a burial memorial.

As the 19th century rolled into the 20th century and transportation costs declined, imported stones became more common, particularly marbles and coloured granites. Closer to home, reconstituted (powdered and reformed) stone became a lower cost alternative to real stone, a common type of which was called coade stone. At first this resulted in an increased diversity of materials, forms and styles, but as the 20th century advanced, the whole business of burials became far more standardized. This is not a reflection of falling standards, but it is an indication of cultural change in general, where Anglican Christianity in particular is of less importance in Britain and where society tends to internalize loss rather than expressing it.

The only grave marker that I have spotted so far that is neither stone nor pseudo-stone is a single metal cross in Overleigh New Cemetery, shown just below, although I am sure that there must be others.

Some graves have inscriptions formed of lead letters, which makes them stand out to ensure that they are easy to read, but they have a very poor survival rate, with letters falling out, and only the pin-holes where they were affixed surviving. This can be sufficient to work out the original inscription, but makes some of the the headstones look rather derelict. In the example shown left, the lettering under the missing lead can still be made out, but this is rarely the case.

Combined, these different materials, with their very contrasting textures and colours, offer a far more diverse visual fare than the modern cemetery areas in both Overleigh and elsewhere, which are usually glossy black granite. They help to contribute to the sense of individuality and personal expression in the cemetery.

Black-painted metal memorial to Frederick, aged 66-77, and Alice Wynne, John Meacock and Robert and Alice Taylor.

Memorabilia and gifts

Bird on a plinth at the foot of Harriett Garner‘s grave

A gravestone was a fixed point, although not invulnerable, whilst gift of flowers, immortelles and other objects are the ore transient but personal markers of ongoing memories or the establishment of new connections between people and graves. As well as demonstrating a personal connection between the living and the dead, the offerings of all types help to keep the sense that the cemetery is still a place of relevance, where narratives continue to be written and rewritten, sometimes only in people’s individual minds, and sometimes shared amongst families and even amongst sections of specific communities.

In the next section, below, is a photograph of Mabel Francis Ireland-Blackburn, showing a three year old child lying in a bed. It is surrounded by modern memorabilia, including flowers (fresh and everlasting) and a variety of toys and other items.

Although it does not attract the same devotion as Mabel, the grave of the suicide Harriett Garner features a charming little bird, probably a robin, on a thoughtful makeshift stand accompanying the grave. It gives the grave a personal touch, something more intimate than the headstone itself, suggesting a sense of ongoing empathy and regret.

War grave of Marjorie Anne Tucker, Women’s Royal Air Force, died 1918 aged 32, with a textile wreath placed by the members of Handbridge Women’s Institute

In the baby cemetery area and the cremation Garden of Reflection in Overleigh Old Cemetery and in the area of recent graves in Overleigh New Cemetery there are many graves with personal memorabilia and gifts from the living to the departed, and these speak to the realities of grief and the importance of reinforcing memory through small gifts and commemorations.

Examples that are cared for by today’s cemetery regulars

Not all graves are appreciated exclusively by their families and descendants. Others have become interesting or even important to people who otherwise have no connections to the deceased. Some graves have attained something of a celebrity status, either because of their visual appeal or because of the reputation or story of their owners, and are particularly cared for by local people as well as by the Friends of Overleigh Cemetery. These graves form a sense of how modern minds can connect on a personal and private level with graves with which they have no familial connection.

Grimsby News, September 11th 1908, reporting the coffin of William Biddulph Cross (The British Newspaper Archive)

The nicely shaped but otherwise unremarkable headstone of electrical engineer William Biddulph Cross, who died in 1908, conceals an amusing story of a coffin made entirely of matchboxes, thousands of them, by William himself over a ten year period, a fact mentioned on the gravestone: “WILLIAM BIDDULPH CROSS / Who Passed Away September 5th 1908 / Aged 85 Years / Known By His Galvanic Cures / And The Maker Of His Own Coffin.” The “galvanic cures” refer to a somewhat scary electrical therapy device thought to be a cure-all for numerous ailments. You can read more about the device and the theory behind it on the National Archives website. The coffin became something of a local tourist attraction in its own right before William was laid to rest, and was widely reported in newspapers all over Britain. The newspaper paragraph to the right, for example, was reported in the Grimsby News. It has been suggested that the electrical fittings were for lighting, but interment before death was a fear throughout the entire Victorian period, and there are some examples of coffins being fitted with devices to allow those who had been mistakenly certified dead to be given a means of raising the alarm, and perhaps this is an alternative explanation. The grave also commemorates six other members of the family who died between 1870 and 1904. It is something of a puzzle to me as to why William BIddulph Cross was the first of these to be named but the last to die.

Mabel Francis Ireland-Blackburn, died 1869. Overleigh Old Cemetery

A particularly notable example is “chewing-gum girl,” which is a rather frightful name for a clearly much-loved grave, explained in Part 4. The grave is a very good example of a modern phenomenon where people feel a strong connection to a grave in the past and demonstrate their sense of affinity and empathy by visiting the grave and leaving items to keep the deceased company. The three year old girl, Mabel Francis Ireland-Blackburn, is represented in stone as a child lying in a bed, and is today surrounded by flowers (cut and artificial), small stone statuettes, toys, a teddy bear by her head, and other small gifts. She died of whooping cough, but was reputed to have suffocated on chewing-gum, becoming a warning anecdote told by parents to their children, in the form of a poem, of the dangers of following in her footsteps. Child grave memorials are discussed more in Part 4. The visual impact of this grave, with the sleeping or dead girl lying in her small bed, propped up on a pillow, is clearly the impetus for the gifts, demonstrating the power of the sculptural funerary image, but also the connection that adults feel for deceased children.

Whilst some graves attract particular attention and are well cared for, The Friends of Overleigh Cemetery are trying to look after the cemetery as a whole, tackling individual problems as they identify them and attempting to rescue stones that can be freed from vegetation without doing them damage.

Cemeteries and the bereaved today

The only new interments in the Old Cemetery are baby burials, segregated with respect and sorrow in a separate garden of their own, or where rights are retained to be interred in a family plot. The attractive cremation Garden of Reflection, with its hedges emulating ripples on the former lake, is also still in use, and it is possible that it will be extended. Both are clearly distinguished from the majority of graves of the previous two centuries by virtue of the fresh flowers and other gifts that are regularly provided. In the New Cemetery, the buildings are no longer in use for funerary activities, and the older part of the cemetery to a great extent resembles many parts of the Old Cemetery, but walk beyond these features and you will find yourself in a far more modern cemetery area, which is clearly frequently visited by family and friends. This is the newer style lawn cemetery where a compromise has been sought between the needs of relatives and the problems of maintenance. This will be discussed in Part 3.

The only new interments in the Old Cemetery are baby burials, segregated with respect and sorrow in a separate garden of their own, or where rights are retained to be interred in a family plot. The attractive cremation Garden of Reflection, with its hedges emulating ripples on the former lake, is also still in use, and it is possible that it will be extended. Both are clearly distinguished from the majority of graves of the previous two centuries by virtue of the fresh flowers and other gifts that are regularly provided. In the New Cemetery, the buildings are no longer in use for funerary activities, and the older part of the cemetery to a great extent resembles many parts of the Old Cemetery, but walk beyond these features and you will find yourself in a far more modern cemetery area, which is clearly frequently visited by family and friends. This is the newer style lawn cemetery where a compromise has been sought between the needs of relatives and the problems of maintenance. This will be discussed in Part 3.

Modern cemeteries issue rules and guidelines about the size and type of grave and grave marking permitted, in order to ensure that cemeteries are as easy to maintain as possible, whilst at the same time providing the bereaved with a place to visit and connect with their lost loved ones. This is a very difficult balance to strike, and local authorities who find themselves with the costly task of maintaining old cemeteries as well as modern ones, have the unenviable task of finding cost-effective ways of caring for these important sites of both past and present commemoration and memorialization. This is discussed further in Part 5.

Part 2 Final Thoughts

Yellow sandstone headstone of George Hamilton, son of Alexander and Mary, suffering from rather surrealistic de-lamination that looks like melting ice-cream, as well as a colonization of lichen. (Overleigh New Cemetery)

A graveyard is less about a place of the dead than a place of commemoration, the formation of individual, family and collective memories and the ongoing reinvention of ideas about how to deal with death. Those who have gone before us are still part of our lives, still form part of our physical landscape and can contribute to our inner ideas about mortality and the future. It is possible to get to know the dead than it is the living via their gravestones, their epitaphs and their stories. Individually these are interesting but collectively they combine with other buildings and institutions to contribute to our understanding of the Victorian period and changing funerary traditions thereafter. These changing fashions in funerary practice from the mid-19th century to the present day will be discussed in part 3.

Cemeteries have visitors who come to see particular graves, either due to regular tending of the grave and communion with the deceased, or to find a grave as part of genealogical research, or as for general or more formal interest into social history, art history and archaeological interest in death and memory.

Many of these graves, suffering from de-laminating or eroded inscriptions, and the invasion of ivy, as well as fallen headstones, highlight the importance not only of maintenance activities but of recording as many of the details on gravestones as possible in online, freely available databases.

Gothic style memorial to Thomas Ernest Hales, died 1906 aged 69. In the background are obelisks in rose granite, made popular when the antiquities of Egypt were first published

Cemeteries are fascinating places, and although modern sections are certainly rather understated and somber because of the signs of recent loss and sadness, older sections are very positive keepers of social history and human endeavor, reflecting choices and decisions by both the living and the deceased, in a wonderful arboretum of multiple tree species. These grave monuments lend themselves to close inspection and appreciation not just of the materials, shapes and symbols, but of the stories that they capture about past lives and how we learn about a city’s past through both the material and conceptual cues that cemeteries retain. The information on headstones can be a good place to start with an investigation in archives. This type of information gives a sense both of the communal identity of a provincial town, and the individual identities that make up that community. Of course, those who could not afford graves or were buried in communal graves that were the result of epidemics, are lost from this commemoration of the individual.

As before, my many thanks to Christine Kemp (Friends of Overleigh Cemetery) for all her practical help, her encyclopedic knowledge, and for checking over my facts. Any/all mistakes are my own. Do give me a yell if you find any.

I have quadruple-checked for typos etc, but some always get past me, for which my apologies.

References for all five parts are on a separate page on the blog here.

Overleigh Cemetery, Chester #1 – Introduction to its background and establishment

The Celtic cross style headstone of Robert Walter Russell (d.1909) and his wife Louisa Alma (d.1936) is on the left; the grave of Jane Whitley (d.1912), with its elaborate angel, topped with a cross and provided with a kerb and footstone (which is where the dedication is to be found), is on the right, erected by her husband Captain W.T Whitley, late Royal Artillery, who joined her there in 1936.

I have been to dozens of archaeological and historical burial sites, from prehistory onward, including famous monumental 19th century cemeteries in London, Paris and Havana, but the easiest by far to visit for someone based near Chester are local parish churchyards and the later dedicated Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries built during the Victorian period. Ironically, I know much more about the burial traditions of ancient Egypt than I do about those on my own doorstep. Up until now I have been repairing the gaps in my knowledge by visiting parish churchyards, but Overleigh Cemetery represents a different type of experience altogether, part graveyard and part public green space. Overleigh reflects the growth of urban populations in towns and cities “which massed people on a hitherto unimaginable scale” (Julie Rugg, 2008) and put unmanageable pressure on urban parish churchyards. It also demonstrates both a new idealism in the 19th century, the belief in the development of civic resources for the benefit of the general public, as well as the growing awareness of how disease was spread, the dangers of insanitary conditions, and the need for new approaches to public health. The Victorian cemetery introduced into suburban environments the down-scaled aesthetics of 18th century estate parkland, often with their associated Classical architectural features, made popular by landscape designers like Capability Brown. This touches on the complexities of the Victorian cemetery of which Overleigh was a smaller provincial form albeit clearly influenced by more elaborate examples.

Before I go any further, many thanks are due to Christine Kemp for her marvellous help when I started this mini-project. It would have taken me at least twice as long without her, probably a lot longer, and I would have made errors that she has put right, so I am in her debt. Chris has contributed 1000s of grave descriptions from this and other local cemeteries to findagrave.com, and is a founder member of the Friends of Overleigh Cemetery.

Where the findagrave.com website has an entry for a grave owner, I have added the hyperlink to the photographs used on this page for anyone who wants to read the inscriptions or find out more.

There will be five parts to this piece about Overleigh. Part 1 starts with a very brisk and short overview of Chester in the 19th Century and goes on to look at the establishment, in that context, of Overleigh Old Cemetery and Overleigh New Cemetery, followed by a short introduction to the objectives of research activities that can be carried out using cemetery material (discussed more in other parts) and some final comments. At the end it also lists the sources for the entire five-part series, which will be added to as the series is posted.

- Part 1: Introduction to the background and the establishment of Overleigh Cemetery

- Part 2: The living, the dead and the visitor at Overleigh,

- Part 3: Shifting ideas – the move away from monumental cemeteries towards cremations and lawn cemeteries

- Part 4: The research potential of cemeteries; and Overleigh case studies

- Part 5: The Overleigh Old and New Cemetery today and in the future

—-

Chester in the 19th century

Overleigh Old Cemetery opened in 1850, and the New Cemetery opened in 1879. To put this into some sort of context, here’s a very short gallop through Chester in the mid-19th century.

Chester Tramways Company Horsecar no.4 at Saltney. Source: Tramway Systems of the British Isles

Chester had been connected to the greater canal network in 1736, linking Chester with the Mersey, and was connected to the rail network by 1840, with today’s station opening in 1848. The Grosvenor Bridge opened in 1832, taking the pressure off the Old Dee Bridge. A horse-drawn tram was introduced in 1879 to link the railway station to Chester Castle and the racecourse. This was replaced by an electric service in 1903 after Chester built an electricity plant in 1896, which also allowed the 1817 gas lighting to be replaced. Improved communications brought more prosperity, and from the 1830s to the beginning of the 20th century, Chester had become an affluent town with a growing population. To accommodate this rapidly growing population the city suburbs expanded to the south of the river, with Middle Class suburbs developing at Curzon Park and Queen’s Park, with a new suspension bridge built in 1852 (the current one replaced it in 1923) to connect the latter to the town.

Chester Town Hall of 1869. Photograph by Jeff Buck, CC BY-SA 2.0

Signs of prosperity were everywhere. Commerce in the markets, shops and local trades thrived in the mid 19th century, and the sense of confidence and ambition was reflected in the expansion of the 18th century Bluecoat Hospital School, the building of the new Town Hall of 1869, the restoration of old buildings, and the establishment of new buildings, many in the style of earlier medieval half-timbering, as well as churches, including those for Dissenters. With its extensive retail, its race course, its regatta and its medley of fascinating architecture, Chester was becoming a popular destination for visitors, and a series of hotels were built to support the growing tourist industry.

Although the Industrial Revolution did not revolutionize Chester in the same way that it did in other towns and cities, it left its mark, although in a rather piecemeal fashion. As with most towns of the period it had light industry concentrated around the canal basin, as well as over the river in Saltney, and a declining shipbuilding industry. Industries included new steam mills, a lead works, an anchor and chain works, three oil refineries and a chemical works amongst other enterprises. Craft trades included tailoring, shoe-making, milliners, dressmaking, bookbinders, cabinet makers, jewelers and goldsmiths, amongst others. In both town and suburban houses domestic service was an important source of employment for the less well off, as was gardening. In line with the Victorian interest in civic works and promoting education and health, the Grosvenor Park opened in 1867 and the Grosvenor Museum in 1885.

Louise Rayner’s (1832–1924) painting of Eastgate Street and The Cross looking towards Watergate Street. Source: Wikipedia

Although the face of Chester seen by most people was a gracious attractive and prosperous one, there was also a lot of poverty. For those who were not quite on the breadline, but could not afford expensive accommodation a solution was provided by lodging houses of variable quality and pricing, which were growing in number to cater for both temporary visitors and more long-term residents. Far more troubling, there were also slum areas known as “the courts,” which housed the city’s poor. The St John’s parish became particularly notorious but these too were expanding, extending into the Boughton, Newtown and Hoole areas. As agriculture made increasing use of labour-saving techniques, former agricultural labourers and their families moved to urban centres to find work. At the same time, the appalling Irish Famine of 1845-52 drove starving people out of Ireland, and a large influx of impoverished Irish refugees, including entire families, expanded the poorest quarters of Chester and were a source of considerable concern to the authorities. Although charity and church schools took in some of the poorer children, the most impoverished and vulnerable, sometimes the children of criminals and certainly in danger of becoming criminals themselves, were not at first provided for but the problem was acknowledged and three free schools for impoverished children known as “ragged schools” were built, of which more in Part 4.

According to John Herson there was an economic decline after 1870, during which population numbers fell, and Chester became more focused on its retail and service industries and the development of its tourism. I recommend his chapter in Roger Swift’s Victorian Chester for more information about his discussion of the three phases of Chester’s Victorian past (see Sources at the end).

A solution to overflowing churchyards

Population in Chester and suburbs by year in 19th Century Chester. Source of data: John Herson 1996, Table 1.1, p.14

Polymath and diarist John Evelyn and architect Christopher Wren had both proposed out-of-town cemeteries in the 17th century, but their suggestions had fallen on deaf ears. An exception was the famous Dissenter cemetery at Bunhill Fields, established from a sense of spiritual necessity.

The rising population that lead the living to move to new areas around Chester, was also a problem for churchyards. The condition of Chester’s city churchyards was very poor, in common with other cities and towns throughout the country, and as the population expanded the situation in churchyards became somewhat desperate, and the new cemeteries were a necessity. John Herson’s chapter in Roger Swift’s Victorian England provides a table of population figures for Chester and its suburbs from 1821 to 1911, and this shows that the population was rising rapidly. Rising populations and the concentration of people in towns had lead to parish church cemeteries becoming problematic all over Britain. This was infinitely worse in big-city urban environments where manufacturing industries had become major employers, where the lack of churchyard capacity led to some truly dreadful, squalid scenes representing appalling health risks, but even in a county town like Chester the problem was very real and churchyards there too were struggling to meet demand.

George Alfred Walker’s “Gatherings from Graveyards“

Complaints were growing about the unsanitary condition of full intramural graveyards, and the risks that this represented. Typhoid, typhus, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, measles, influenza and cholera, were all infectious diseases that were common in Victorian England, and the establishment of new graveyards for minimizing risk was becoming increasingly important as the links between health and sanitation were established. Jacqueline Perry says that between 1841 and 1847 the annual average was 700 burials in Chester alone.

Those arguing for a new cemetery in Chester as a response to this problem were able to point to other specialized graveyards in Britain and overseas. Bigger city cemeteries had been established earlier in the 19th century in Paris (in 1804 Père La Chaise was the first municipal cemetery in western Europe), Liverpool (Liverpool Low Hill opened in 1825 and St James’s Cemetery opened in 1829). In 1830 George Carden, after years of campaigning, organized a meeting to discuss how to improve the burial situation in London and Kensal Green opened in 1833, which initiated “The Magnificent Seven” ring of London cemeteries. Glasgow’s remarkable Necropolis followed in 1833.

In 1839 surgeon George Alfred Walker published his Gatherings from Graveyards (including the subtitle And a detail of dangerous and fatal results produced by the unwise and revolting custom of inhuming the dead in midst of the living), which drew uncompromising attention to some of the horrors of churchyards, encouraging burial reform and the wider adoption of the out-of-town cemetery. I have provided a link to an online copy of this book in the Sources, but it is absolutely not for the faint-hearted. Although this trend was challenged by the Church of England, which derived an income from burial fees, the need was acute, and parish churches were compensated for their loss of income. Most of these new cemeteries were commercial, charging for burials and paying dividends to investors from their profits.

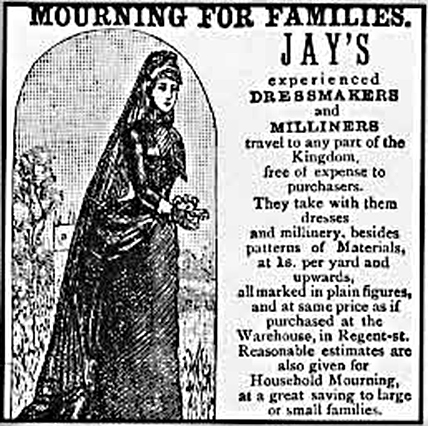

Mourning clothes were a major investment in the Victorian funeral ceremonies. Source: Wikipedia

There was also clearly a psychological need for new cemeteries with neatly defined and delineated plots for individuals and families, and the space to commemorate and mourn loved ones. As James Stevens Curl explains: “It could never be said that the Victorians buried their dead without ceremony. Apart from the immediate family, all the distant relatives would be present . . . Friends, business associated, acquaintances would all appear . . . A dozen or sometimes more coaches therefore followed the hearse.” The acts of observance and the rituals associated with death in the Victorian period, and the traditions associated with the bereavement that followed interment were elaborate, encoded and important to Victorian religious beliefs and social conventions. These beliefs and conventions were part of a deeply felt attitude to death and how it should be handled. They were also opportunities to display wealth and status for those who had it. The new landscape-style cemeteries offered the opportunity to carry out these various rituals at each stage of bereavement after loss with dignity and ceremony.

Following the new cemeteries and the success of the concept, cemetery design became a recognized field of endeavor for landscape designers and architects, and the best known cemetery designer, although by no means the first or even the best, was probably John Claudius Loudon, who consulted on a number of projects before publishing his 1843 On the Laying Out, Planting and Managing of Cemeteries, which became an important source of practical advice and creative ideas for many private enterprises. Loudon’s intentions are captured in these two statements from the beginning of his book:

Cemetery design for a hilly location by Thomas Loudon, 1834, showing a similarly sinuous arrangement as Overleigh, but with the building centred at the heart of the cemetery. Source: Loudon 1843

The main object of a burial-ground is, the disposal of the remains of the dead in such a manner as that their decomposition, and return to the earth from which they sprung, shall not prove injurious to the living; either by affecting their health, or shocking their feelings, opinions, or prejudices.

A secondary object is, or ought to be, the improvement of the moral sentiments and general taste of all classes, and more especially of the great masses of society.

The means by which Loudon proposed to address his “secondary object” was by introducing a sense of serenity, providing fresh air and a sense of nature, and encouraging contemplation. At the time disease was thought to be conveyed by “miasmas” or vapours, not entirely unsurprising given how bad cesspits, uncovered drains and overfilled graveyards smelled, and trees were thought to assist with the absorption of miasmas, helping to promote good health and prevent the spread of disease. Often his designs were based on a grid, like the 1879 Overleigh New Cemetery, but his above design for cemeteries on hills and slopes, like the Overleigh Old Cemetery was more forgiving.

Sculptural monument on a plinth dedicated to land agent and surveyor Henry Shaw Whalley, d.1904

After the 1850s commercial cemeteries were not the standard way of establishing new cemeteries. The Metropolitan Interments Act allowed for burial grounds to be purchased by a civic authorities, which was itself replaced by a new Act of Parliament in 1852 when Burial Boards were established, after which publicly funded cemeteries became the norm.

One of the results of the new cemeteries, with individual plots dedicated to single individuals or to families, was that graves became part of the domestic sphere of families, part of their personal real estate. In an elaborate cemetery this might include personal family mausolea and vaults, but at a more modest provincial cemetery like Overleigh, it usually consisted of a sculptural element or a headstone with a kerb and sometimes a footstone, although at Overleigh footstones are unusual (all the elements are in the grave shown at the top of the page, on the right). This created a clearly defined space in which family and friends could commemorate their dead with gifts of flowers and sometimes additional memorabilia. The main sculpture or headstone, usually of stone but occasionally of metal, was itself a medium for expression, combining shapes, symbolic and sentimental imagery, and text to express ideas about both the dead and their relationship to the living. The kerbs were usually visited and the dead were gifted fresh flowers or immortelles (more permanent artificial flowers presented in suitable vessels or frames, sometimes under a glass dome).

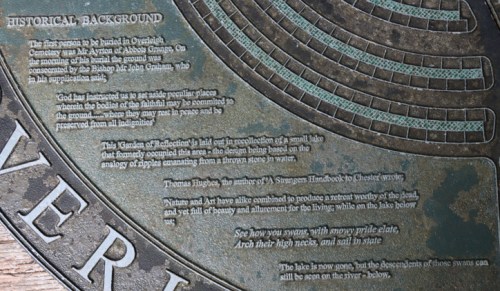

Overleigh Old Cemetery

Overleigh Old Cemetery, very convenient for Chester residents without intruding on the town itself, lies just across the Grosvenor Bridge, its northern border running along the south bank of the river Dee. It has gateways from the Grosvenor Bridge, Overleigh Road and River Lane which converge on the monument of, cenotaph to William Makepeace Thackeray, a Chester doctor and benefactor. Although this is the oldest of the two halves of the cemetery, it is still in use today for new cremation memorials in its maze-like hedged memorial area (actually designed to look like ripples on the lake that once occupied the space), as well as an enclosed area for interments and cremated ashes of babies, which is inevitably particularly sorrowful. Overleigh Old Cemetery is often used as a short-cut from the Grosvenor Bridge to the walkway along the Dee, and presumably as its designer Thomas Penson originally intended, always has the feeling of a public park as much as a cemetery, although up until late August 2024, there has been nowhere to sit. A bench supplied by the Friends of Overleigh Cemetery has helped to bring the cemetery further into the public domain.

The cemetery was established by The Chester Cemetery Act in 1848. Chester’s City Surveyor, Mr Whally had held a public inquiry at the Town Hall to discuss the urgent need of a new extramural cemetery. Overleigh was established by a private company named the Chester General Cemetery Company, which was formed by an Act of Parliament on 22nd July 1848. According to Historic England, the cemetery site was owned by the Marquis of Westminster who exchanged it for a shareholding in the company. The cost of the cemetery was estimated at £5000 but the company blew its budget and in 1849 work was forced to stop for seven months until new shareholders could be found. The thinking behind it was, much like the Grosvenor Park and the museum, as much a matter of civic pride as it was a practicality. However, unlike the park or the museum, the cemetery was intended to turn a profit, and was essentially a retail operation, selling or renting burial plots, paying for its own maintenance and offering a return on shareholder investment, and providing a valuable service to residents at the same time.

Crypt Chambers, Eastgate Street. Source: Wikipedia

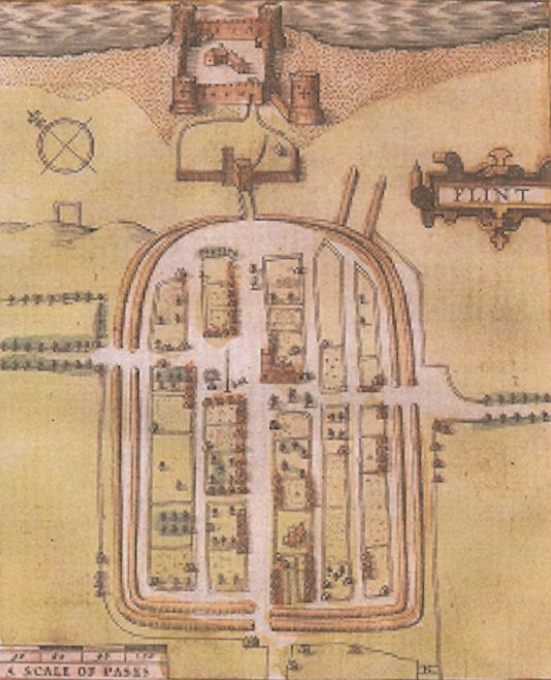

Overleigh Old Cemetery was designed by Thomas Mainwaring Penson (1818–1864), the surveyor and architect responsible for, amongst other Chester buildings, the 1858 Crypt Chambers and the 1868 Grosvenor Hotel, both on Eastgate Street. The original layout of Overleigh Old Cemetery is preserved in an engraving from sometime after it opened, shown below, probably in the later 1850s.

Following the model already established in Paris, Belfast, Glasgow, Liverpool and London, this was a garden- or landscape-type cemetery, planned to emulate a large garden or small park. When compared with some of the vast architectural entrances to the great Victorian cemeteries of Liverpool, Glasgow, London and elsewhere (see, for example, Kensal Green or, in a different style, the Glasgow Necropolis) the gates at Overleigh are a mere nod to a transitional zone between the busy outside world and the quiet necropolis within, with modest pillars and iron gates, shown above. The buildings that were once just inside each gate, the entrance lodges, will have given more of sense of entry and exit than the entrances retain today. Something of that effect can be seen over the road at Overleigh New Cemetery where the lodge building survives. The funeral cortege would stop here to be formally received and recorded before proceeding to the burial site.

Overleigh Cemetery. Source: Wikipedia