The magnificent Rhuddlan Castle, and its predecessor Twthill motte-and-bailey castle (the latter now just a mound), are located just over 3 miles south of the point on the North Wales coast where the river Clwyd, which Edward I diverted to pass the foot of Rhuddlan, empties into the sea at Rhyl. Like all of Edward I’s newly built English castles in Wales, this has some features in common with its brethren, but is at the same time a unique entity, each with a highly distinctive, unmistakable appearance in its own right, building on previous creativity to create even more innovative defensive measures.

I visited Rhuddlan last week for the first time, taking spur-of-the-moment advantage of a cold but gloriously sunny morning to make the most of Rhuddlan’s striking looks and lovely location. The castle is an impressive sight, particularly as it is bounded on its northeastern side by fairly dense village housing and one gets the sense of emerging abruptly from the bustling present into a peaceful and finely fossilized landscape of the past.

I visited Rhuddlan last week for the first time, taking spur-of-the-moment advantage of a cold but gloriously sunny morning to make the most of Rhuddlan’s striking looks and lovely location. The castle is an impressive sight, particularly as it is bounded on its northeastern side by fairly dense village housing and one gets the sense of emerging abruptly from the bustling present into a peaceful and finely fossilized landscape of the past.

This is the third post in an occasional series about the history of Edward I’s earliest castles in northeast Wales. The background history to Edward’s sudden launch into castle building in Wales from 1277 is the first part, and can be found here. It looks at the disputes between Edward I’s father Henry III, king of England, and his subsequent and far more personally felt disputes with Llywelyn ap Gruffud, Llywelyn the Last of Wales. The second post in the series looked at Flint Castle, the first of Edward’s castles in Wales started in July 1277, with its accompanying new town. Rhuddlan Castle was started in September 1277, and is covered below. Denbigh built in 1282 is posted about here.

St Mary’s Rhuddlan

I combined Rhuddlan Castle with a look at the last surviving chunk of Edwardian defensive ditch that originally surrounded the town, and a wander around the exterior of the nearby St Mary’s Church (its opening times to visitors are limited to the summer months), which was built sometime after the granting of the town charter in 1278, both of which are mentioned below. I then skirted the castle and followed the track and footpath down to Twthill. The story of life at Rhuddlan before Edward I, both pre- and post-Norman, will be covered on another post, and will include the background to and history of Twthill.

St Asaph’s Cathedral

After Rhuddlan I drove the few miles south to visit St Asaph Cathedral, which has connections to both Rhuddlan Friary, originally located near the castle, and Valle Crucis Abbey, near Llangollen. Valle Crucis is the subject of an ongoing series of posts on this blog. Rhuddlan Friary has been discussed on the blog here, and St Asaph Cathedral will be discussed on a separate post at a later date.

To make it an official day-trip, the day not being warm enough for an ice cream, I stopped for a very self-indulgent glass in The Hare in Farndon on the way home, which was the cherry on top of a very good day!

Visitor information for Rhuddlan Castle is at the end of the post.

Rhuddlan during the reign of Henry III

Henry III (reigned 1216-1272), father of Edward I, had ongoing problems with self-styled Prince of Wales Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, also known as Llywelyn the Last, a grandson of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great). Llywelyn was based in Gwynedd, his home territory, but had managed to establish some degree of unity within his own family (particularly his brothers Dafydd and Owain) and throughout Wales, historically a fragmented and constantly shifting set of territories. The powerful Marcher lordships along the Welsh border formed an aggressive barrier between Wales and the rest of England, and trouble had rumbled continuously along the border during the reigns of previous kings, causing the official border between the two countries to move regularly. The crown held territories within modern Wales, and these came under attack by Llywelyn the Last. This is all covered in the post that describes the background to the disputes between Edward and Llywellyn, complete with a family tree of the relevant participants.

Henry III (reigned 1216-1272), father of Edward I, had ongoing problems with self-styled Prince of Wales Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, also known as Llywelyn the Last, a grandson of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great). Llywelyn was based in Gwynedd, his home territory, but had managed to establish some degree of unity within his own family (particularly his brothers Dafydd and Owain) and throughout Wales, historically a fragmented and constantly shifting set of territories. The powerful Marcher lordships along the Welsh border formed an aggressive barrier between Wales and the rest of England, and trouble had rumbled continuously along the border during the reigns of previous kings, causing the official border between the two countries to move regularly. The crown held territories within modern Wales, and these came under attack by Llywelyn the Last. This is all covered in the post that describes the background to the disputes between Edward and Llywellyn, complete with a family tree of the relevant participants.

A Dominican priory, described on the blog here, was founded by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1258 during the reign of Henry III, and is discussed. The building does not survive, but some of its materials were visibly incorporated into the farm that now sits on the original site of the priory. It is quite likely that during the 13th century played host to Llywelyn ap Grufudd, and later to both Henry III and Edward I during their visits. As with most monastic institutions, the Dominicans were obliged to show hospitality to guests, irrespective of their political allegiance, and it would have been in their interests to stay in the good graces of both Welsh and English leaders. Edward had probably taken advantage of hospitality at Basingwerk Abbey during the construction of Flint Castle.

A Dominican priory, described on the blog here, was founded by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1258 during the reign of Henry III, and is discussed. The building does not survive, but some of its materials were visibly incorporated into the farm that now sits on the original site of the priory. It is quite likely that during the 13th century played host to Llywelyn ap Grufudd, and later to both Henry III and Edward I during their visits. As with most monastic institutions, the Dominicans were obliged to show hospitality to guests, irrespective of their political allegiance, and it would have been in their interests to stay in the good graces of both Welsh and English leaders. Edward had probably taken advantage of hospitality at Basingwerk Abbey during the construction of Flint Castle.

Edward I’s Rhuddlan Castle

Expanding the the “Ring of Iron”

Map of Edward I’s campaigns in Wales. Source: History Matters at the University of Wales

Edward was granted the royal lands in Wales by Henry III on the occasion of his marriage to Eleanor of Castille, and took an active interest in the Welsh situation until his departure on crusade, during which his father died. Edward inherited the dispute with Llywelyn, but was already very familiar with the the Welsh prince and his ambitions, and was also familiar with the Welsh landscape. The expenses incurred during his crusade had left him with serious debts, and the terms of the agreement that Llywelyn had reached with Henry III involved a substantial annual payment by the Welsh prince to the Crown treasury, but there were problems. Llywelyn was already three years in arrears, and was now refusing to pay homage to the new king. Several treaties under Henry III had failed to achieve long term peace, and although the Treaty of Montgomery of 1267 had looked as though it might hold, Llywelyn ap Gruffud’s behaviour was intolerable to Edward who labelled Llywelyn an outlaw in 1276, and war was declared in 1277. A peace was brokered, but although Edward had every reason to believe that the treaty might secure peace between England and Wales, he began to build a series of castles in northeast Wales, eventually extending into northwest Wales, beginning at Flint in the July of 1277 and rolling out along the coastlines throughout the next two decades. This was followed almost immediately by the foundation of Rhuddlan in the same year.

Artist’s impression of the Twthill motte-and-bailey castle by Terry Ball. All that survives today is the motte. Source: Wikipedia

When Edward started building his castle at Rhuddlan in September 1277, Flint Castle and town were still under construction. Flint had been virgin territory, and consisted of both a stone castle and a new defended town, an “implanted bastide.” Although the site of Edward’s castle itself had not been occupied, Rhuddlan had been long-established, from the pre-Conquest period into the 13th century. The existing wooden Twthill motte-and-bailey castle, a short distance from Rhuddlan probably served as a useful base from which to manage building works and campaigns as the new stone castle was built and the new town laid out and provided with perimeter defences.

Llywelyn, realizing that his cause was lost, surrendered later in 1277 at Rhuddlan, several years before Edward’s castle was finished, and for a while it looked as though the resulting Treaty of Aberconwy would provide the basis for long-term peace. Llywelyn had been granted the entire region of what is now known as Gwynedd, permitted to retain the title Prince of Wales, and his difficult brother Dafyddd was allocated territories in mid-north Wales whilst Owain was given control of the Llŷn peninsula. Edward, however, was not taking any chances, and he continued with his castle building programme, unambiguously reinforcing his message that Wales was under English control, with Rhuddlan performing the role as the administrative headquarters for the region. Should any attempts at rebellion be attempted in the future, Edward and his supporters would be ready.

Llywelyn, realizing that his cause was lost, surrendered later in 1277 at Rhuddlan, several years before Edward’s castle was finished, and for a while it looked as though the resulting Treaty of Aberconwy would provide the basis for long-term peace. Llywelyn had been granted the entire region of what is now known as Gwynedd, permitted to retain the title Prince of Wales, and his difficult brother Dafyddd was allocated territories in mid-north Wales whilst Owain was given control of the Llŷn peninsula. Edward, however, was not taking any chances, and he continued with his castle building programme, unambiguously reinforcing his message that Wales was under English control, with Rhuddlan performing the role as the administrative headquarters for the region. Should any attempts at rebellion be attempted in the future, Edward and his supporters would be ready.

Why Rhuddlan?

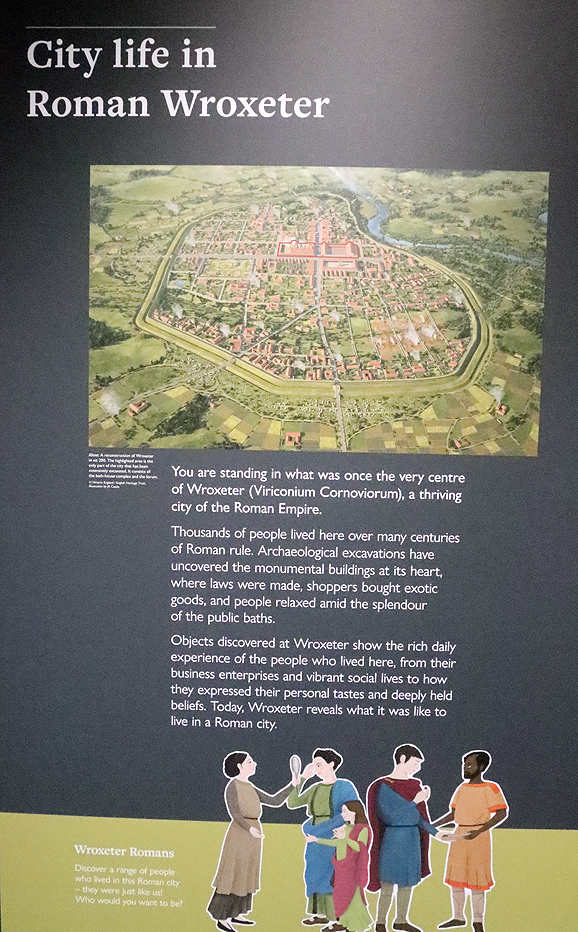

What were the strategic advantages that made Edward I choose Rhuddlan as the location for his third castle, his new administrative headquarters for north Wales?

What were the strategic advantages that made Edward I choose Rhuddlan as the location for his third castle, his new administrative headquarters for north Wales?

First, the castle is right on the edge of the River Clywd, a fairly narrow but very attractive ribbon of blue threading its way between the fields, all the more impressive when you know that the river actually ran along a slightly different course until Edward canalized it and had it dredged to provide a deep-water channel for connecting the castle to the coast and the Dee Estuary. The River Clywd become un-navigable not far south of Rhuddlan. The link to the estuary connected Rhuddlan both to Flint Castle and Chester to its east and then, later, to Edward’s castles at Conwy and Caernarvon in the west.

Photograph of Rhuddlan Castle in the context of the River Clwyd floodplain and the coast to the north. Rhuddlan Castle is at bottom left, near the rear foot of the RCAHMW dragon logo. Source: Coflein, archive number 6356180 / AP_2007_2032

The castle itself sits above a very wide, low floodplain, on an area of raised land. Standing on the battlements, reached by modern spiral staircases, the views over the surrounding landscape are remarkable, providing an excellent impression of how well the castle was positioned for sighting oncoming threats. Economically, the wide floodplain was ideal for the development of a new town, with potential for raising livestock and agriculture.

Until Conwy was built, Rhuddlan was conveniently located as a regional HQ just on the edge of Llywelyn’s territory, and it was his most important base in Wales. By the time Conwy Castle was up and running, Rhuddlan had become secondary in importance, but was still garrisoned and was very important in Edward’s chain of defences.

The Designers and the Design

The outer curtain wall, which only survives in very small sections, followed the perimeter of the revetted dry moat, and enabled archers in the battlements of the castle to fire over the heads of those protecting the outer defences.

Rhuddlan has a very distinctive look and feel to it, containing some innovative features that were carried through to other castles in the northeast. The first architect to work on Rhuddlan, who was probably responsible for its layout and some of its initial design elements, was king’s engineer Master Bertram, who had been employed by Henry III is Gascony, and who brought with him Gascon design principles. He was replaced after six months by Master James of St George, whose work Edward had seen in France at the castle of St Georges d’Esperanche, and who went on to build Edward’s great castles at Conwy, Caernarvon, Harlech and Beaumaris.

The most obvious novel feature of the design, when compared to Flint, was the use of both an inner and a very short outer curtain wall, shown in the photograph above, a concentric arrangement of defences that formed the template for Edward’s later castles, including nearby Denbigh, built in 1282. The lower outer curtain wall, which at Rhuddlan was installed along the inner perimeter of a revetted dry moat, itself impressively lined with stone, enabled archers on the battlements of the main castle to aim beyond those defending the outer curtain wall without endangering them, whilst providing two lines of defence for the castle and its defenders.

Originally a formal gateway granted access across the moat and the short outer curtain wall into the riverside entrance between the first pair of distinctive twinned towers. Diagonally across the inner ward a second pair of twinned towers gave access via a secondary entrance. On the other two corners of the main castle were another two towers, each single. All the towers, including the river tower, were 4 storeys high, including a subterranean basement in each.

Building the castle

The first task was to build defensive ditches, which which would offer protection for the construction camp as the castle was built, and would later become the dry moat. At Flint Castle 1800 ditchers, known as fossatores, were employed for thus task, as well as the digging of the ditch and banks for the town defences, and it is probable that a similar number was employed at Rhuddlan, sourced from all over England, some of whom were forced labour. It is possible that a proportion of the fossatores who had been employed at Flint were now deployed at Rhuddlan.

The first task was to build defensive ditches, which which would offer protection for the construction camp as the castle was built, and would later become the dry moat. At Flint Castle 1800 ditchers, known as fossatores, were employed for thus task, as well as the digging of the ditch and banks for the town defences, and it is probable that a similar number was employed at Rhuddlan, sourced from all over England, some of whom were forced labour. It is possible that a proportion of the fossatores who had been employed at Flint were now deployed at Rhuddlan.

As the castle began to take shape, skilled craftsmen were also imported, including carpenters and masons. Carpenters would have been vital for the build, as they were responsible for the scaffolding as well as various buildings in both inner and outer wards, and other architectural features. Masons used a mixture of stone types for the construction, all available locally, including yellow and red sandstones, the latter more vulnerable to erosion over the centuries than the yellow, and the grey limestone. Extensive robbing from the lower levels of the castle after it was slighted (damaged to prevent re-use) after the English Civil War in the 17th Century gives the impression of a serious attack of delamination, but as peculiar as it looks helpfully reveals the underlying construction, showing that the the more enduring limestone covered more vulnerable sandstones.

As the castle began to take shape, skilled craftsmen were also imported, including carpenters and masons. Carpenters would have been vital for the build, as they were responsible for the scaffolding as well as various buildings in both inner and outer wards, and other architectural features. Masons used a mixture of stone types for the construction, all available locally, including yellow and red sandstones, the latter more vulnerable to erosion over the centuries than the yellow, and the grey limestone. Extensive robbing from the lower levels of the castle after it was slighted (damaged to prevent re-use) after the English Civil War in the 17th Century gives the impression of a serious attack of delamination, but as peculiar as it looks helpfully reveals the underlying construction, showing that the the more enduring limestone covered more vulnerable sandstones.

View of Rhuddlan from the west showing what it may have looked like by the beginning of the 14th century. Illustration by Terry Ball. Source: Taylor / Cadw 2004, p.3

In 1278 sufficient progress had been made for the king and queen to stay at the castle, and in 1280 the towers were roofed in lead and in 1281 the king’s hall was roofed with shingles. A well was sunk into the centre of the inner ward, 50ft deep.

Whilst work on the castle proceeded, one of the most impressive of the civil engineering feats at Rhuddlan was completed simultaneously. The river Clwyd was diverted from its natural course, and canalized for two miles (3.5km), the work of 968 workers who were imported to Rhuddlan for the task in 1277, providing the castle with deep channel access to the coast, suitable for sea-going vessels, avoiding the need for trans-shipping. This met Edward’s requirement for a fluid and seamless communications network.

There was space by the riverside tower, known today as Gillot’s Tower, for a single vessel to put in to dock at high tide, and a river gate alongside the tower, improving efficiencies for loading and unloading. As Rhuddlan always had a garrison, and was on a number of occasions the base from which forces departed towards Snowdonia, it was often provisioned from Ireland with livestock and grain. A military cemetery was established at the castle, a clear indication that Edward was expecting casualties in his dealings with Wales.

There was space by the riverside tower, known today as Gillot’s Tower, for a single vessel to put in to dock at high tide, and a river gate alongside the tower, improving efficiencies for loading and unloading. As Rhuddlan always had a garrison, and was on a number of occasions the base from which forces departed towards Snowdonia, it was often provisioned from Ireland with livestock and grain. A military cemetery was established at the castle, a clear indication that Edward was expecting casualties in his dealings with Wales.

Work was suspended during renewed hostilities in 1282, when Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd instigated another rebellion against Edward I. Dafydd attacked Hawarden Castle on 21st March, Palm Sunday. His action encouraged other Welsh landholders to retaliate in kind, but it was not until June that Llywelyn took the decision to join his brother’s rebellion. Although the Welsh rebellion seemed to gain ground for a while, the English assembled a substantial force at Rhuddlan, consisting of around 9000 men, which advanced into Wales taking several Welsh castles as they proceeded. The castle was re-provisioned by ship from Ireland with livestock and cereals. This time there was no peace treaty, and Llywelyn was killed on the battle field in the same year, whilst Dafydd was eventually caught in June 1283 and held at Rhuddlan Castle before being put on trial in Shrewsbury for treason, after which he was tortured and executed. The cost was massive, some £120,000 (£83,288,423.43 in today’s money, according to the National Archives Currency Converter) with £50,000 having been raised by a tax on English residents. There was also a huge cost in terms of English life; the military cemetery established at Rhuddlan had run out of space by October 1282.

Work was suspended during renewed hostilities in 1282, when Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd instigated another rebellion against Edward I. Dafydd attacked Hawarden Castle on 21st March, Palm Sunday. His action encouraged other Welsh landholders to retaliate in kind, but it was not until June that Llywelyn took the decision to join his brother’s rebellion. Although the Welsh rebellion seemed to gain ground for a while, the English assembled a substantial force at Rhuddlan, consisting of around 9000 men, which advanced into Wales taking several Welsh castles as they proceeded. The castle was re-provisioned by ship from Ireland with livestock and cereals. This time there was no peace treaty, and Llywelyn was killed on the battle field in the same year, whilst Dafydd was eventually caught in June 1283 and held at Rhuddlan Castle before being put on trial in Shrewsbury for treason, after which he was tortured and executed. The cost was massive, some £120,000 (£83,288,423.43 in today’s money, according to the National Archives Currency Converter) with £50,000 having been raised by a tax on English residents. There was also a huge cost in terms of English life; the military cemetery established at Rhuddlan had run out of space by October 1282.

Work had resumed on Rhuddlan following the conflict and although there are no records of damage to the castle at that time, records of repairs do survive and these suggest that Rhuddlan had come under attack. A record survives for the payment of 64 shillings to “Adam the tailor” for red silk to make pennons and royal standards for Rhuddlan. As if the massive castle itself was not a sufficient statement of English power in the region, it was to be adorned with the rich and brightly coloured symbols of English monarchy.

Work had resumed on Rhuddlan following the conflict and although there are no records of damage to the castle at that time, records of repairs do survive and these suggest that Rhuddlan had come under attack. A record survives for the payment of 64 shillings to “Adam the tailor” for red silk to make pennons and royal standards for Rhuddlan. As if the massive castle itself was not a sufficient statement of English power in the region, it was to be adorned with the rich and brightly coloured symbols of English monarchy.

The 50ft / 15m well in the inner ward

Today it is difficult to conceive of a royal court that was constantly on the move, but in the Medieval period, royal authority was reinforced by the movement of the monarch to properties around his kingdom, both his own and those of favoured aristocrats. After the execution of Dafydd, Edward took his court on a tour of various provincial areas, whilst work continued at Rhuddlan. He was back at Rhuddlan for Christmas. Between 1283 and 1286 further investment was made on the royal apartments and chapel, both of which would have been in the wooden buildings in the inner ward, together with the kitchens. Beam holes in the walls of the castle’s interior show where the roof beams were installed. A well was sunk in the centre of the inner ward. The outer ward would also have been filled with buildings, of a more utilitarian variety, including at least one granary, a forge, stables and storage facilities.

Arnold Taylor quotes a figure of £9613 2s 8 3/4d for the building of Rhuddlan between 1277 and 1282. According to the National Archives Currency Converter, this would be some £6,672,184.58 in today’s money (or 11,209 horses or 21,362 cows or 961,313 days of a skilled tradesman’s labour).

Edward’s new borough and town

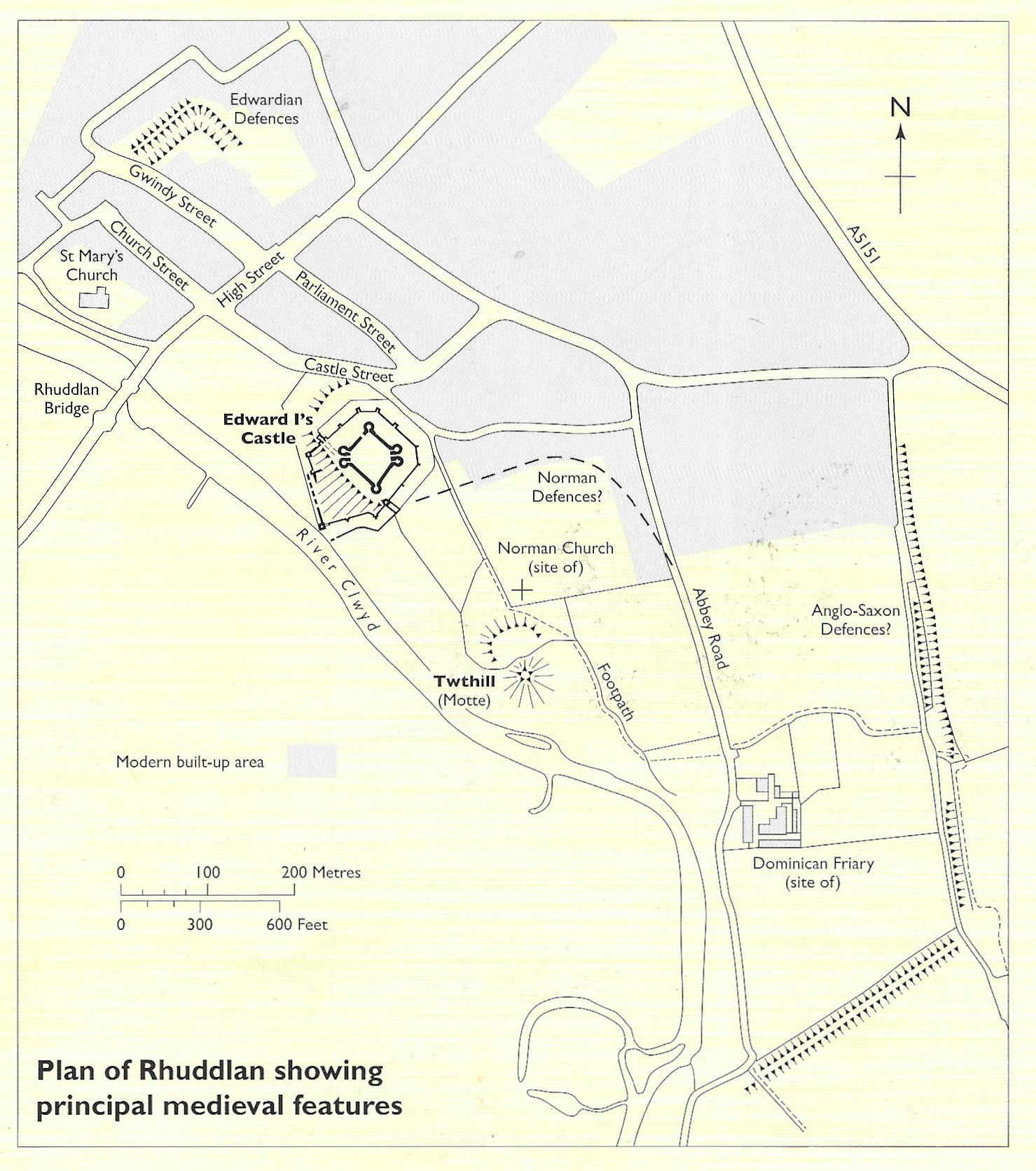

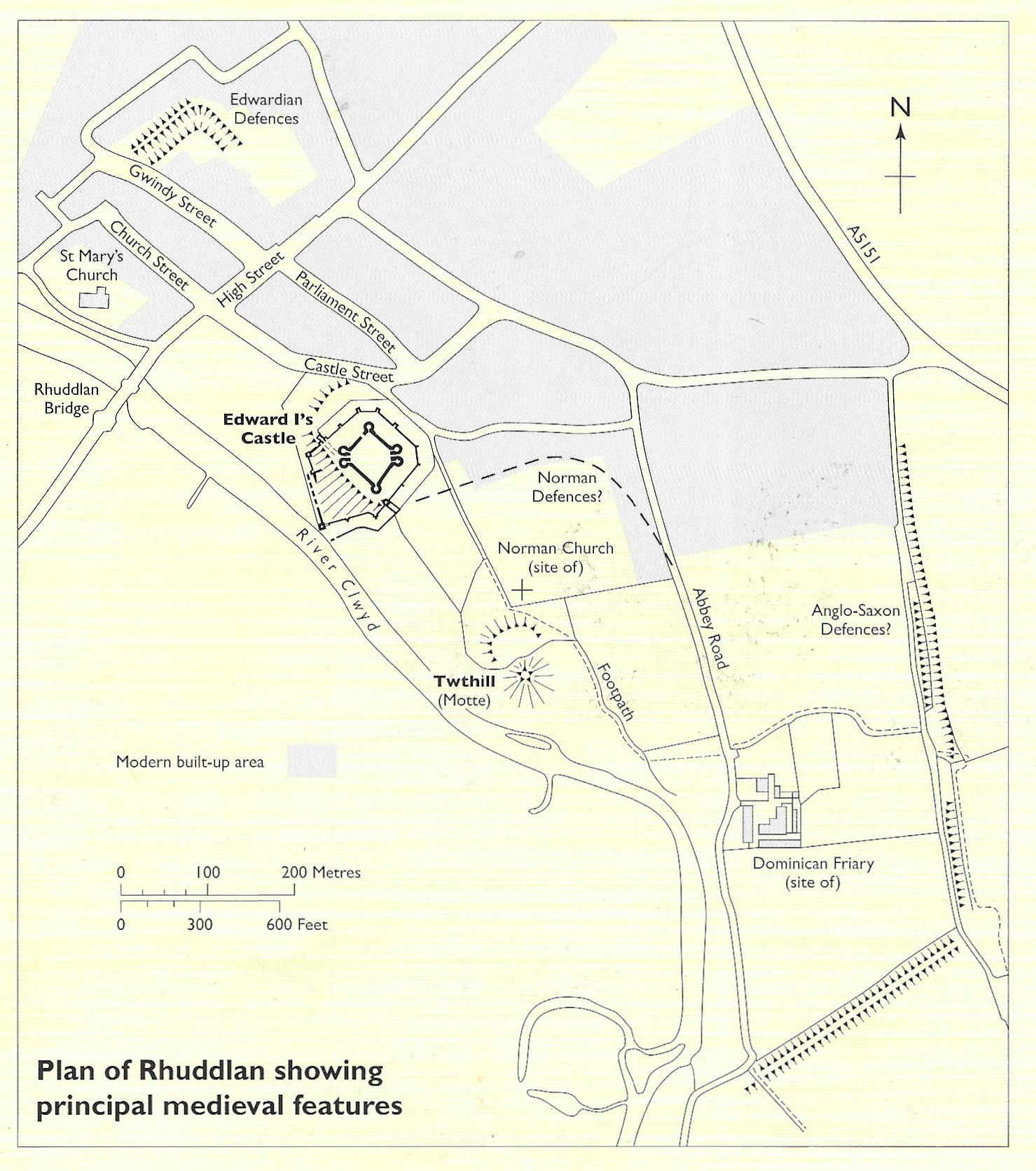

Plan of Rhuddlan. Source: Arnold Taylor/Cadw 2004, p.9

As at Flint a new borough was created and provided with defences and English settlers were incentivized to live and work there. The new town, known as an “implanted bastide” after prototypes in Gascony, was built to the northwest of the the old town and was granted its charter in 1278. This new-town bastide concept and its management are discussed in more detail on the post about Flint Castle. Today’s town follows the original layout of the new town, its streets originally dividing the town into five sections leading down to a bridge across the river, with the High Street, Church Street, Castle Street, Parliament Street and Gwindy street being the key survivors.

The town was defended on three sides by a ditch with flanking banks, possibly topped with a timber palisade, a section of which survives off Gwindy Street, shown in the illustration and photograph below. In the 1960s the complete length of the ditch survived north of the town, but by 1970 only the Gwindy Street section remained. Excavation of part of the defences, known as Plot 0, was undertaken when the land was due to be sold for development, but due to the heavily eroded state of the banks was unable to confirm if there were timber defensive features. The fourth side of the defences was made up by a cliff running down to the river.

Source: Quinnell and Blockley 1994

====

What remains of the double banks and ditch that surrounded the new town of Rhuddlan

Although it might have seemed like an unattractive proposition to be an immigrant English population living in a defended town in ostensibly hostile territory, there was a huge demand for land in England at that time, and the new towns in Wales represented great opportunity as well as risk, particularly as charters offered far more favourable conditions for the English than their Welsh neighbours. Marc Morris refers to them as “those enclaves of English privilege, where the Welsh were obliged to trade but could not live and where the legal discrimination between the two peoples was a fact of every day existence.” The risk for these settlers was very real, and it was the towns rather than the castles that were targeted by Dafydd in 1282, in Aberystwyth, Denbigh and Rhuddlan.

===

The Statute of Rhuddlan of March 1284

In 1284 Edward I formalized how Wales to was to be governed and ruled after the deaths of Llywelyn in 1282 and Dafydd in 1283 during Dafydd’s ill-conceived rebellion of 1282. The document that captured his requirements was the Statute of Rhuddlan or Statue of Wales, which was issued by Edward I from Rhuddlan whilst he was in residence. Although Edward had been sufficiently diplomatic to recognize different interests and hierarchical claims within Wales after 1277 for the sake of peace, in 1282 his aim was to bring the entire of Wales into a single administrative system controlled by England.

The Statue of Rhuddlan, part territorial administration and part legal treatise, handled Wales as a single homogenous unit, an extension of England and her criminal legal system. Wales was divided into new English-style shires: Flint, Merioneth, Caernarvon, Anglesey, Cardigan and Carmarthen, a structure that endured until 1536 when the Act of Union was passed. An English administrative hierarchy was put into place with officials and administrators answering to a new justiciar based in northwest Wales. Legally, the Statue was an interesting mixture of English law with some concessions to Welsh traditions. Criminal law was English, but the Statute allowed for Welsh traditions of civil law to be maintained for matters like contracts, inheritance, land deals and debt handling.

Edward’s castle building continued unabated even as the statute was being written up in Rhuddlan, announced and enforced. It is thought that it was at Rhuddlan that Edward declared that the title and role of prince of Wales would pass to his own son and to the future sons of English kings. Edward’s first child, who became Edward II, was born at Caernarfon in April 1284, in the month following the statute, and was officially granted the title of Prince of Wales in 1301. The title has been handed down from reigning monarch to eldest son ever since that date, most recently on the death of Queen Elizabeth II when, the former Prince of Wales, Charles, having acceded to the throne on 10th September 2022, the title passed to his eldest son, Prince William.

Edward’s castle building continued unabated even as the statute was being written up in Rhuddlan, announced and enforced. It is thought that it was at Rhuddlan that Edward declared that the title and role of prince of Wales would pass to his own son and to the future sons of English kings. Edward’s first child, who became Edward II, was born at Caernarfon in April 1284, in the month following the statute, and was officially granted the title of Prince of Wales in 1301. The title has been handed down from reigning monarch to eldest son ever since that date, most recently on the death of Queen Elizabeth II when, the former Prince of Wales, Charles, having acceded to the throne on 10th September 2022, the title passed to his eldest son, Prince William.

Rhuddlan Castle after Edward I

Rebellion of October 1294

Resentment in Wales continued to fester, and in October 1294 Madog ap Llywelyn, a relation of Llyweln the Great, and Morgan ap Maredudd, both important land owners in northwest Wales laid siege to Edward’s castles at Criccieth, Conwy and Harlech. This followed particularly harsh taxes imposed by Edward, that discriminated against the Welsh, and also Edward’s demand for men to fight in Gascony. Rhuddlan served as a jumping-off point for Edward’s response to this uprising in March 1295, but Conwy was by now at the heart of the action, and Edward’s new headquarters whilst Caernarfon Castle was still being built (and which was damaged during the attack). By June 1295 the uprising had been put down and order was restored.

Resentment in Wales continued to fester, and in October 1294 Madog ap Llywelyn, a relation of Llyweln the Great, and Morgan ap Maredudd, both important land owners in northwest Wales laid siege to Edward’s castles at Criccieth, Conwy and Harlech. This followed particularly harsh taxes imposed by Edward, that discriminated against the Welsh, and also Edward’s demand for men to fight in Gascony. Rhuddlan served as a jumping-off point for Edward’s response to this uprising in March 1295, but Conwy was by now at the heart of the action, and Edward’s new headquarters whilst Caernarfon Castle was still being built (and which was damaged during the attack). By June 1295 the uprising had been put down and order was restored.

Owain Glyn Dŵr, 1400-c.1410

In 1400, during the reign of Henry IV, Owain Glyn Dŵr, having been declared Prince of Wales by a group of his followers met at Glyndyfrdwy, lead a new rebellion in response to harsh conditions imposed by the English crown, and Rhuddlan was one of the castles and towns that came under attack. Rhuddlan Castle held out against the assault, but the town itself was brutalized, and there are indications such as the failure to properly repair town defences that the borough never recovered.

The English Civil War, c.1642-51

In the Civil War of 1642-48, the castle was held by the king’s forces but although it initially held out, it was surrendered to the parliamentarian commander-in-chief Major-General Thomas Mytton, and a decision was made in the House of Commons to slight the castle (render it unusable), which was actioned in May 1648. This was the fate of several medieval castles that were employed during the Civil War.

Rhuddlan Castle in 18th and 19th century art

In my posts about Flint and Denbigh I had a look at some of the art works that were produced in the 18th and 19th centuries when medieval buildings with their air of romance and mystery found an enthusiastic audience amongst painters of all skill levels. There are so many art works of Rhuddlan that it is almost impossible to pick and choose, so I have selected views that show different aspects of the castle, and have added a link at the end of Sources to some more examples.

John Boydell was a publisher, talented engraver and promoter of art, as well as doing a stint as Lord Mayor of London. His 1749 image above not only captures the castle but the attached village and the distinctive bridge and that captures something of village life, with men fishing, a barge pulled up at the river edge, and people approaching on horseback and foot. The strongly featured bridge is typical of his work – in 1747 he published The Bridge Book, featuring six landscapes all of which showcased distinctive bridges. He did a rather nice one of Denbigh Castle too.

From the 1781 edition of “A tour In Wales” by Thomas Pennant (1726-1798) Source: Wikipedia via the National Library of Wales

Thomas Pennant was born in Flintshire and is best known for his remarkable A Tour In Wales, which eventuallyran to eight illustrated volumes, capturing three journeys that he made in Wales between 1773 and 1776. The National Library of Wales says that one of his greates gifts was “his ability to foster friendships. His appreciation of people was very well-known and because of this he always received sensible and full answers to all his enquiries for information.” He was a great collector, but his interest was always in the subject matter and the details captured, rather than particular artistic merit. The painting of Rhuddlan below was in the 1781 edition, capturing something of the sense of the isolation of the castle in a wide landscape, a contrasting and more delicate approach to Boydell’s bright and lively image.

Rhuddlan Castle as captured by artist George Pickering (1794-1857) and engraved by George Hawkins the Younger (1819-1852). See the National Library of Wales catalogue for a bigger image in which details can be clearly seen.

A completely different approach was taken by lithographer George Pickering the Younger, who got up close and personal with the castle, sacrificing the general form of the castle in favour of picking out particular features. He artist looks out over the river and the floodplain beyond, the sun low in the sky, with village buildings shown in the background, including St Mary’s Church. The ivy clinging to the towers is also shown on Peter Ghent’s painting below. Cattle are shown grazing on the foreshore, a small sailing vessel is pulled up on the other side of the bridge, and there are other visitors inspecting the site.

Rhuddlan Castle c.1885 by Peter Ghent (1857–1911). Williamson Art Gallery and Museum. Source: ArtUK

The oil on canvas painting of Rhuddlan Castle by Peter Ghent, now at the Williamson Art Gallery and Museum in Birkenhead, is a rather more impressionistic view of the castle, showing the ivy and the surrounding trees, and cattle cooling themselves in the river. The riverside tower is not shown, although part of the river wall is shown. The russet and green palette is characteristic of Ghent’s work. Ghent was born in Birkenhead and attended Birkenhead School of Art. He moved to Conwy, which he used as a base for exploring Welsh landscapes in both oil and watercolour.

===

Rhuddlan Castle Today

The castle was given into state care in 1944 and conservation work began in 1947. It was transferred from the Department of the Environment to the newly created Cadw, the Welsh Government’s historic environment service, in 1984. It is beautifully cared for, without a single blade of grass out of place. The ivy that once ran riot over its walls has been completely eliminated which given how invasive ivy is was a considerable task. The castle continues to undergo conservation work as needed to prevent deterioration and to ensure that it remains safe.

The castle was given into state care in 1944 and conservation work began in 1947. It was transferred from the Department of the Environment to the newly created Cadw, the Welsh Government’s historic environment service, in 1984. It is beautifully cared for, without a single blade of grass out of place. The ivy that once ran riot over its walls has been completely eliminated which given how invasive ivy is was a considerable task. The castle continues to undergo conservation work as needed to prevent deterioration and to ensure that it remains safe.

The castle was deliberately slighted (i.e. partly demolished) at the end of the English Civil War in the 16th century so that it could not be reused in any future offensives, which accounts for its ruined state. This does not impede an understanding of the castle and its features, many of which remain. Some of the damage is more recent. The lower courses of stone have been extensively robbed since the 16th century for local construction projects, revealing the inner filling of the walls, and leaving it looking very denuded and rather peculiar at its ground floor level, but allowing the inner construction of the thick walls to be seen.

Although there are no floors left in the towers and inner walls, there are fireplaces and beam slots (the beams supporting the floors at each level) that show where each of the storeys was located. Some of the fireplaces, like the one on the left, retain black burn marks, a really evocative link to the past. Many of the fireplaces were quite huge and, given the diameter of the towers, must have provided substantial heat for the castle guardians and administrators who were based there even in the coldest Welsh winters, even if the space was a little cramped.

Although there are no floors left in the towers and inner walls, there are fireplaces and beam slots (the beams supporting the floors at each level) that show where each of the storeys was located. Some of the fireplaces, like the one on the left, retain black burn marks, a really evocative link to the past. Many of the fireplaces were quite huge and, given the diameter of the towers, must have provided substantial heat for the castle guardians and administrators who were based there even in the coldest Welsh winters, even if the space was a little cramped.

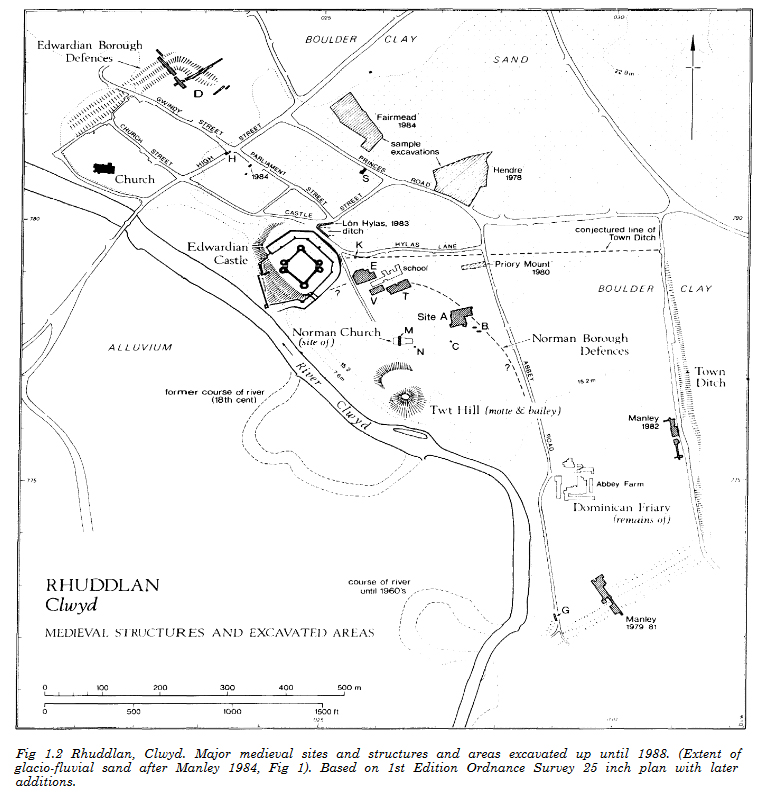

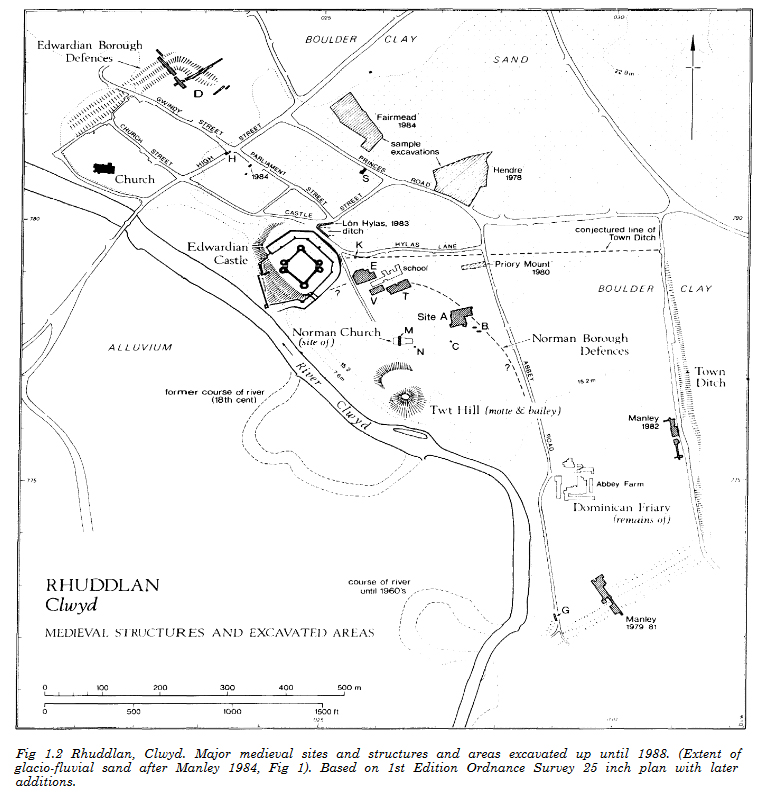

A number of modern excavations have been carried out at Rhuddlan, between 1973 and 1988 helping to clarify some details about the medieval history of Rhuddlan as well as information about earlier phases, particularly during the Norman and prehistoric periods (Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age, including some particularly fine lithics and decorated pebbles dating to the Mesolithic). These are summarized by Quinnell and Blockley in their 1994 publication, which can be downloaded from the Archaeology Data Service website.

Excavated Areas in Rhuddlan between 1969 to 1973. Click to expand. Source: Quinnell and Blockley 1994, p4

Excavated object from Rhuddlan. Source: Quinnell and Blockley 1994, p.184

St Mary’s Church, Rhuddlan

St Mary’s, only a five minute walk from the castle, was closed when I visited, so I am going to cover it on another post next summer when it re-opens to visitors, but it is certainly worth mentioning here, as it looks as though it is a splendid piece of later medieval heritage. An earlier Norman church was built to the east of the castle, but St Mary’s was first built in 1284 and was enlarged in the 15th century. It has undergone changes over the years, and perennial multi-tasker Sir George Gilbert Scott had a go at it during his restoration of St Asaph’s Cathedral in the 1900s, but by all accounts the restoration appears to have been quite sympathetic. The gilbertscott.org website reports that “Scott treated the old building gently, lowering the floor in the nave and raising it in the chancel, providing some new windows, seating, a vestry and rebuilding the south porch. He also provided a vestry screen, pulpit, an eagle lectern, altar rail and chancel seats.” However, Quinnell and Blockley say that the church contains much of the original 13th century architecture in the nave and chancel. They add that fragments from two different crosses, found during the demolition of a wall near the Vicarage in 1936, are now kept in the church. Both have inter-laced decoration and have been dated stylistically to the late 10th or early 11th centuries.

St Mary’s, only a five minute walk from the castle, was closed when I visited, so I am going to cover it on another post next summer when it re-opens to visitors, but it is certainly worth mentioning here, as it looks as though it is a splendid piece of later medieval heritage. An earlier Norman church was built to the east of the castle, but St Mary’s was first built in 1284 and was enlarged in the 15th century. It has undergone changes over the years, and perennial multi-tasker Sir George Gilbert Scott had a go at it during his restoration of St Asaph’s Cathedral in the 1900s, but by all accounts the restoration appears to have been quite sympathetic. The gilbertscott.org website reports that “Scott treated the old building gently, lowering the floor in the nave and raising it in the chancel, providing some new windows, seating, a vestry and rebuilding the south porch. He also provided a vestry screen, pulpit, an eagle lectern, altar rail and chancel seats.” However, Quinnell and Blockley say that the church contains much of the original 13th century architecture in the nave and chancel. They add that fragments from two different crosses, found during the demolition of a wall near the Vicarage in 1936, are now kept in the church. Both have inter-laced decoration and have been dated stylistically to the late 10th or early 11th centuries.

If you are there when it is open, it should be well worth visiting at the same time as a trip to the castle (unfortunately the St Mary’s website does not currently show the times when it is open to visitors, but there is an email address). Even though it was closed, I very much enjoyed a walk around the building and a poke around the churchyard. Gravestones and their symbolism are eternally fascinating and there are some very good examples of churchyard monuments.

If you are there when it is open, it should be well worth visiting at the same time as a trip to the castle (unfortunately the St Mary’s website does not currently show the times when it is open to visitors, but there is an email address). Even though it was closed, I very much enjoyed a walk around the building and a poke around the churchyard. Gravestones and their symbolism are eternally fascinating and there are some very good examples of churchyard monuments.

Final Comments

Rhuddlan is visually stunning, and retains plenty of its newly innovated features to capture interest, demonstrating significant improvements in medieval castle design. The canalized river showcases both Edward’s obsession with good communication links and the civil engineering skills that were available to him. As a visitor attraction it is beautifully maintained by Cadw, which is particularly noticeable when comparing it with earlier images of the castle covered in ivy. Rhuddlan attracted a serious amount of artistic interest, providing views of how it looked in the 18th and 19th centuries and, at the same time, demonstrating the fascination that artists had for medieval ruins. This is a site that really rewards a visit, particularly on a bright sunny day, when the red and yellow sandstones absolutely glow against a blue sky.

Rhuddlan is visually stunning, and retains plenty of its newly innovated features to capture interest, demonstrating significant improvements in medieval castle design. The canalized river showcases both Edward’s obsession with good communication links and the civil engineering skills that were available to him. As a visitor attraction it is beautifully maintained by Cadw, which is particularly noticeable when comparing it with earlier images of the castle covered in ivy. Rhuddlan attracted a serious amount of artistic interest, providing views of how it looked in the 18th and 19th centuries and, at the same time, demonstrating the fascination that artists had for medieval ruins. This is a site that really rewards a visit, particularly on a bright sunny day, when the red and yellow sandstones absolutely glow against a blue sky.

Visiting Rhuddlan Castle

Rhuddlan is operated by Cadw, and is subject to an entry fee. Details of opening times and entry charges are on the Cadw website. There is a free car park, which also has a map of the main features of the town and the route down to Twthill, just five minutes away from the castle. Beyond Twthill, the footpath passes the Abbey Farm and caravan park, the site of the former Rhuddlan Friary, which is on private land and cannot be visited.

As usual with Cadw venues, there is not much information about the history of Rhuddlan on the Cadw website, but there are plenty of online resources and there is an excellent short (9-page) Cadw guide book available from the ticket office, or from online book retailers, with a 3-D reconstruction and a site plan, as well as a history of the site and a numbered tour of the key features, each with a descriptive paragraph explaining what you’re looking at – well worth the £2.50 that it cost me in the Rhuddlan Castle gift shop. You are also given a site plan as part of the ticket price, with 7 features picked out and described briefly (bi-lingual English and Welsh).

My battered copy of the Cadw leaflet that is provided with your ticket, showing some of the key features of the castle. The reverse side shows the same details in Welsh.

===

The approach to the castle is on the flat, as is the interior and the walk around the castle, so this is suitable for those with unwilling legs. As with Flint Castle, the towers are fitted with modern spiral staircases, which will probably not be suitable for unwilling legs, but there is plenty to see without scaling the heights, including excellent views over the floodplain.

The approach to the castle is on the flat, as is the interior and the walk around the castle, so this is suitable for those with unwilling legs. As with Flint Castle, the towers are fitted with modern spiral staircases, which will probably not be suitable for unwilling legs, but there is plenty to see without scaling the heights, including excellent views over the floodplain.

The ticket office also has toilets and a small gift shop. There are no coffee facilities but there is a freezer with ice-creams and a fridge with cold drinks, and there are some tables and chairs outside for a sit down.

It’s a seriously attractive site, and well worth a visit.

Sources

Books and papers

Davis, Paul R. 2021. Towers of Defiance. The Castles of Fortifications of the Princes of Wales. Y Lolfa

Davies, John 2007 (3rd edition). A History of Wales. Penguin

Dean, Josh and Catherine Jones 2020. Archaeological Watching Brief report for Plas Llewelyn, Rhuddlan. Project code: A0209.1, report no. 0203. Aeon Archaeology

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/92914

Morris, M. 2008. A Great and Terrible King. Edward I and the Forging of Britain. Penguin

Quinnell, Henrietta and Marion R. Blockley with Peter Berridge 1994. Excavations at Rhuddlan, Clwyd 1969-73. Mesolithic to Medieval. CBA Research Report No 95 (1994)

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-281-1/dissemination/pdf/cba_rr_095.pdf

Rowley, T. 1986. The High Middle Ages, 1200-1550. Routledge and Kegan Paul

Shillaber, C. 1947. Edward I, Builder of Towns. Speculum, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jul., 1947), p.297-309

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2856866

Spencer, Dan 2018. The Castle At War in Medieval England and Wales. Amberley Publishing

Stevens, Matthew Frank 2019. The Economy of Medieval Wales 1067 – 1536. University of Wales Press

Taylor, Arnold. 2004. Rhuddlan Castle. Abridged from a text by Arnold Taylor. Cadw

Websites

Abbey Farm Caravan and Camping Park

History

https://abbeyfarmrhuddlan.co.uk/portfolio-item/history/#top

Balfour Beatty

Balvac repaired this 13th century castle in North Wales

https://www.balfourbeatty.com/what-we-do/projects/rhuddlan-castle/

Cadw

Rhuddlan Castle

https://cadw.gov.wales/visit/places-to-visit/rhuddlan-castle

Rhuddlan, Norman Borough

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/303586

Coflein

Rhuddlan Castle

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/92914

Ecclesiastical and Heritage World

Rhuddlan Castle: Conservation of Castle River Dock

https://www.ecclesiasticalandheritageworld.co.uk/news/1038-rhuddlan-castle-conservation-of-castle-river-dock

Goldin Fine Art

John Boydell: The Enlightenment Man

https://www.goldinfineart.com/blogs/blog/john-boydell?srsltid=AfmBOop6p7_0_WrJ2Sx_WA4FEs0lZW09ZdoRzqo61Hc6WFokRC3aLG9h

National Library of Wales

A Tour In Wales. Thomas Pennant (eight digitized volumes)

https://www.library.wales/discover-learn/digital-exhibitions/pictures/a-tour-in-wales

Sulis Fine Art

Peter Ghent RCA (1857-1911)

https://www.sulisfineart.com/peter-ghent-rca-1857-1911-late-19th-century-watercolour-cottage-by-a-stream-qo859.html

Rhuddlan Castle in Art

Meisterdrucke

Rhuddlan Castle and Marshes, 1898, unknown artist

https://www.meisterdrucke.ie/fine-art-prints/Unbekannt/785633/Rhuddlan-Castle-and-Marshes.html

ArtUK

Rhuddlan Castle by John Lawson 1868 – 1909. Glasgow Museums Resource Centre

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/rhuddlan-castle-84929

Darnely Fine Art

Rhuddlan Castle by Norman Wilkinson 1878-1971.

https://darnleyfineart.com/artwork/rhuddlan-castle/

Government Art Collection

Rhuddlan Castle by David Gentleman 1930 –

artcollection.dcms.gov.uk/artwork/17005/

Rhuddlan Castle in Art

Various examples – a good mix

https://jenikirbyhistory.getarchive.net/topics/rhuddlan+castle+in+art

This looks like a must-see exhibition at the Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery. On my to-do list:

This looks like a must-see exhibition at the Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery. On my to-do list: