On this page:

- Introduction to the Parish Church of St Giles

- Who was St Giles?

- Medieval Wrexham

- A brief history of the church

- Highlights of a visit to St Giles

- Final comments

- Visiting details

You can download an image-free version of this post as a PDF, apart from a small site plan, so that the page count and, should you wish to print it, the ink consumption are kept to a minimum. Click here to download.

Introduction

Aerial view of the Parish Church of St Giles from the south. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Grade-1 listed Parish Church of St Giles, (or St Silin or Silyn in Welsh), was the heart of medieval Wrexham and is still the main architectural anchor of the town. It is possible that it lies over the site of an earlier medieval church, perhaps dating to the 11th century. Today’s church, built of local yellow sandstone, dates mainly to the late 15th and early 16th centuries. It is a huge and impressive structure built in two main phases of the gothic style, with five vast windows on the north side and six on the south. None of the glass is original, all dating to the 19th and 20th centuries, but some of it is very fine, and it all gives a sense of how the church would have looked originally.

The tower at the west end and the polygonal chancel at the east end were both added in the early 16th century. The famous tower and the roofs of nave and chancel are elaborately decorated with crenellations and sculptural features. Only a fraction of the original churchyard remains, but you can still do a full circuit around the church and of the remaining grave markers there remain some fine chest-type grave markers.

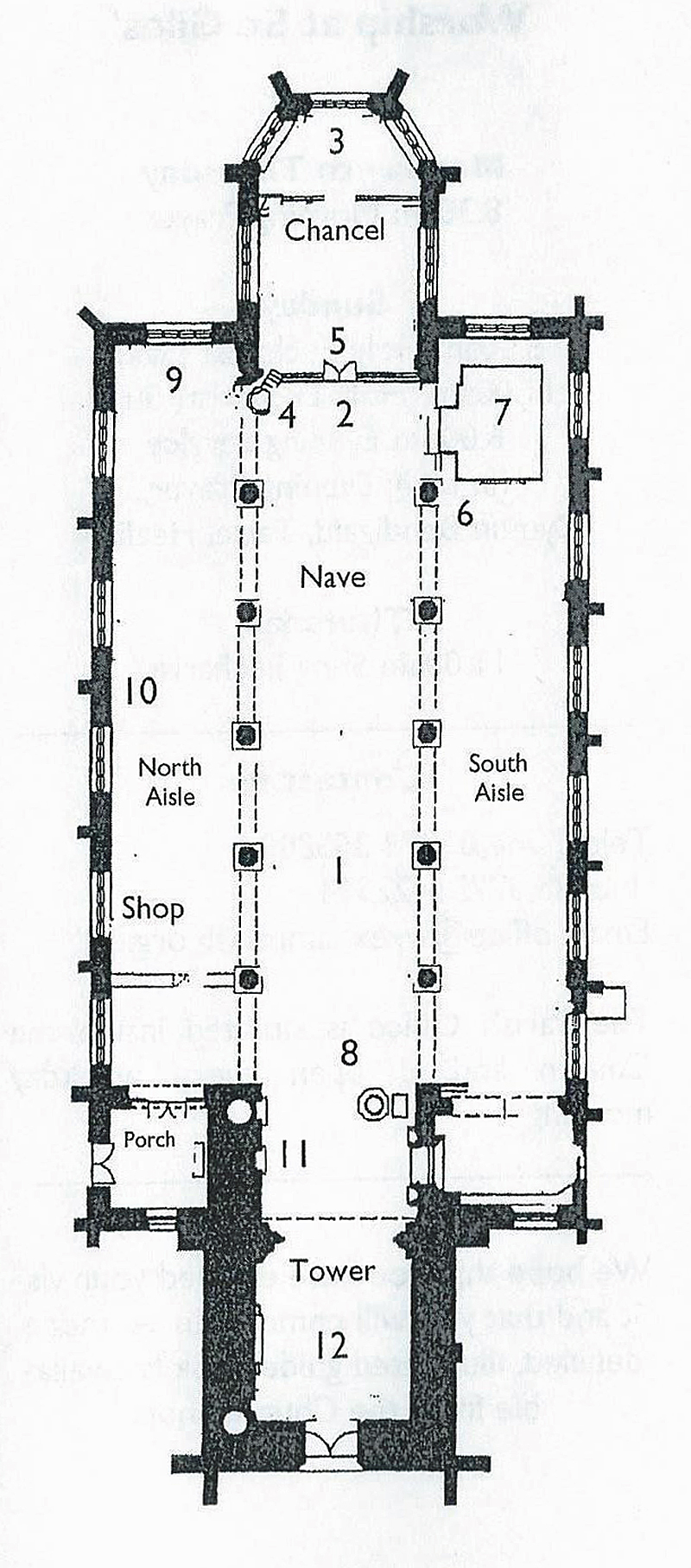

The interior is influenced by the window apertures of the Perpendicular Gothic, but the arcades themselves are more consistent with the earlier Decorative style. At the east end a polygonal chancel (5) with a three-sided apse protrudes (3), with the still remarkable remains of a Doom painting over the chancel arch (over 5). There is a 41m (136 feet) tall tower at the west end (12) that is visible from miles around, and from which the views are reportedly spectacular.

The plan today consists of a nave (1) divided from its flanking north and south aisles by an arcade of six arches. Running along the top of the nave are the clerestories, a row of windows above the level of the aisles that let in light to supplement the stained glass. The east end of the north aisle (the side on which you enter, facing into the town), is now dedicated to the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (9). Opposite this, the east end of the south aisle is fully occupied by the 19th century organ (7) where the medieval Lady Chapel was once located. The organ dates to 1894 and its pipes are very nicely decorated, although it hides a stained glass window aperture and the original piscina. At the western end of both aisles, and lying beyond them, connecting the nave with the tower, is the ante-nave, which is where the font (8) is located.

I have included a summary below of some of what is known about medieval Wrexham, the period that created the main architectural legacy of the church, mainly because I knew so little about it myself before visiting the church. Hopefully it will also help others unfamiliar with Wrexham’s past to put it into some sort of context. I have also included a list of features that I particularly enjoyed. More formal lists of features are available in a leaflet on the table just beyond the north porch in the ante-nave, as well as in a comprehensive and invaluable visitor guide, with lots of photos, available from the church shop, but I have simply singled out the features that particularly grabbed my attention.

Apart from the font (possibly 15th century) stand-alone features such as the brass eagle lectern (16th century) are generally of post-medieval date. The pulpit and pews are all Victorian and the choir stalls are missing, which is a crying shame as they were probably beautifully crafted with sculptural carvings. Inevitably there were 19th century alterations and additions mainly by Benjamin Ferrey in 1866-7, with the chancel refurbished by T.G. Jackson in 1914 and again between 1918 and 1919. For the most part, with notable exceptions such as the chancel reredos, these have been done quite sensitively, usually with the intention of restoring the appearance of the church rather than elaborating the original vision.

Who was St Giles?

According to the guide book (Williams 2018), this is St Giles on the north face of the tower standing on a “grotesque” corbel.

St Giles, whose name in Latin is Aegidius, is one of two saints whose name is associated with the Wrexham parish church. The other is the Welsh saint Silyn, whose name in Latin is also Aegidius, which may explain why the church has different names in English and Welsh. An alternative explanation is that the church of St Giles sits over the site of a much earlier medieval church dedicated exclusively to Silyn.

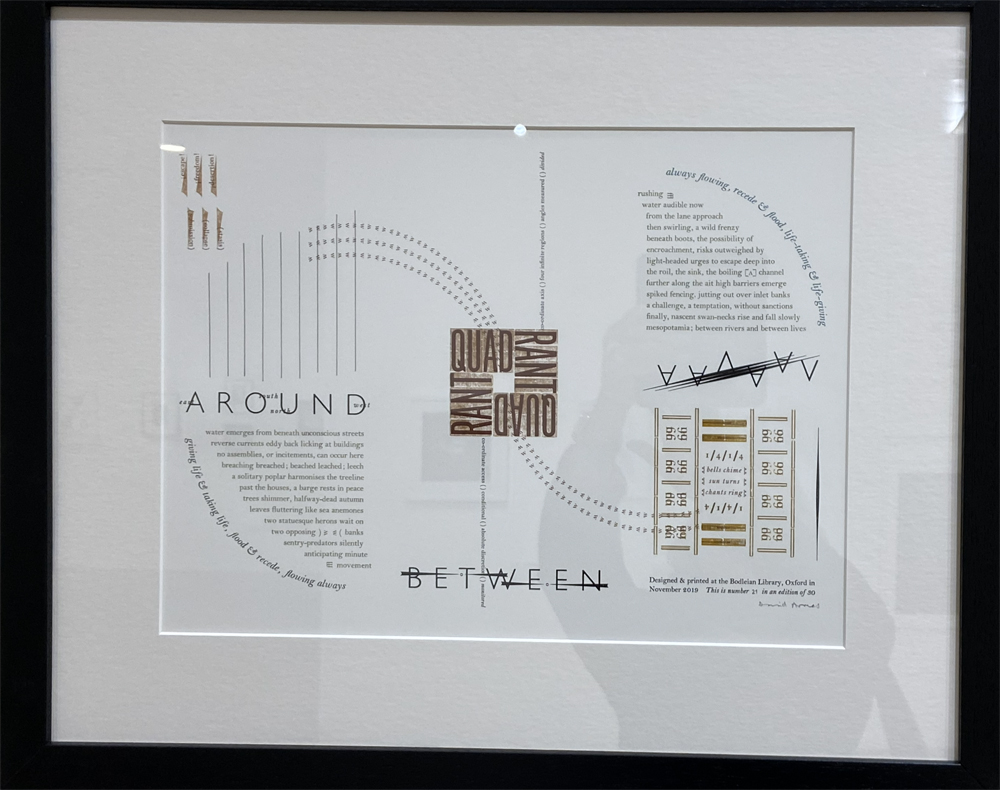

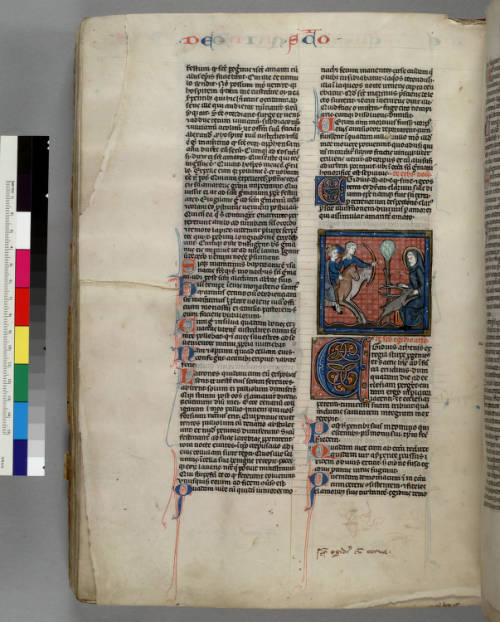

St Giles was featured in the 13th century compilation of nearly 200 stories (hagiographies) of saints called Legenda Aurea (the Golden Legend), by Dominican Friar Jacobus de Voraigne, in which “legend” meant passages of text to be read out aloud. It was designed as a handy tool for preachers who wanted rousing content for their sermons, a who’s who of revered Christian saints. It spread quickly even before the invention of the printing press in the mid 15th century, after which it went viral with over 80 editions printed, with four editions in English. It remains an invaluable resource for understanding which saints were most appreciated throughout the medieval period, what was understood about them and how they were valued as models of divinely approved behaviour. St Silyn was a purely native saint and is not included in the Legenda, but the description of St Giles indicates why he was so valued in the medieval period.

St Giles in the “Legenda Aurea.” mssHM 3027 f.118v. Source: Huntington Digital Library

According to the Legenda, St Giles was an aristocratic Athenian, who died A.D. c.710. His earliest miracle took place when he gave his coat to a sick beggar who, as soon as he put on the coat, was cured. On another occasion Giles prayed for a man who was bitten by a snake, and the poison was driven out. He decided to leave his homeland to escape his spreading fame and head west, and was given passage by some sailors who were saved from wreckage by the saint’s prayers. Having arrived in southern France, where he remained, he stayed for a while with a hermit, before moving away to become a hermit himself with a spring nearby and with the company of a doe who provided milk.

When the doe fled to him for protection during the local king’s hunt, Giles was accidentally pierced by an arrow let loose by one the king’s hunters. Giles miraculously lived, but he prayed for his wound not to be fully healed so that he might experience how “power is made perfect in weakness.” The king, duly impressed, established a monastery and convinced Giles to become its head, which became an important site of pilgrimage.

St Giles, Avignon 1335 (Indulgence from 15 archbishops and bishops for the St. Aegidius / St Giles Chapel of the Teutonic Brothers in Aachen). Source: Picryl (PublicDomain)

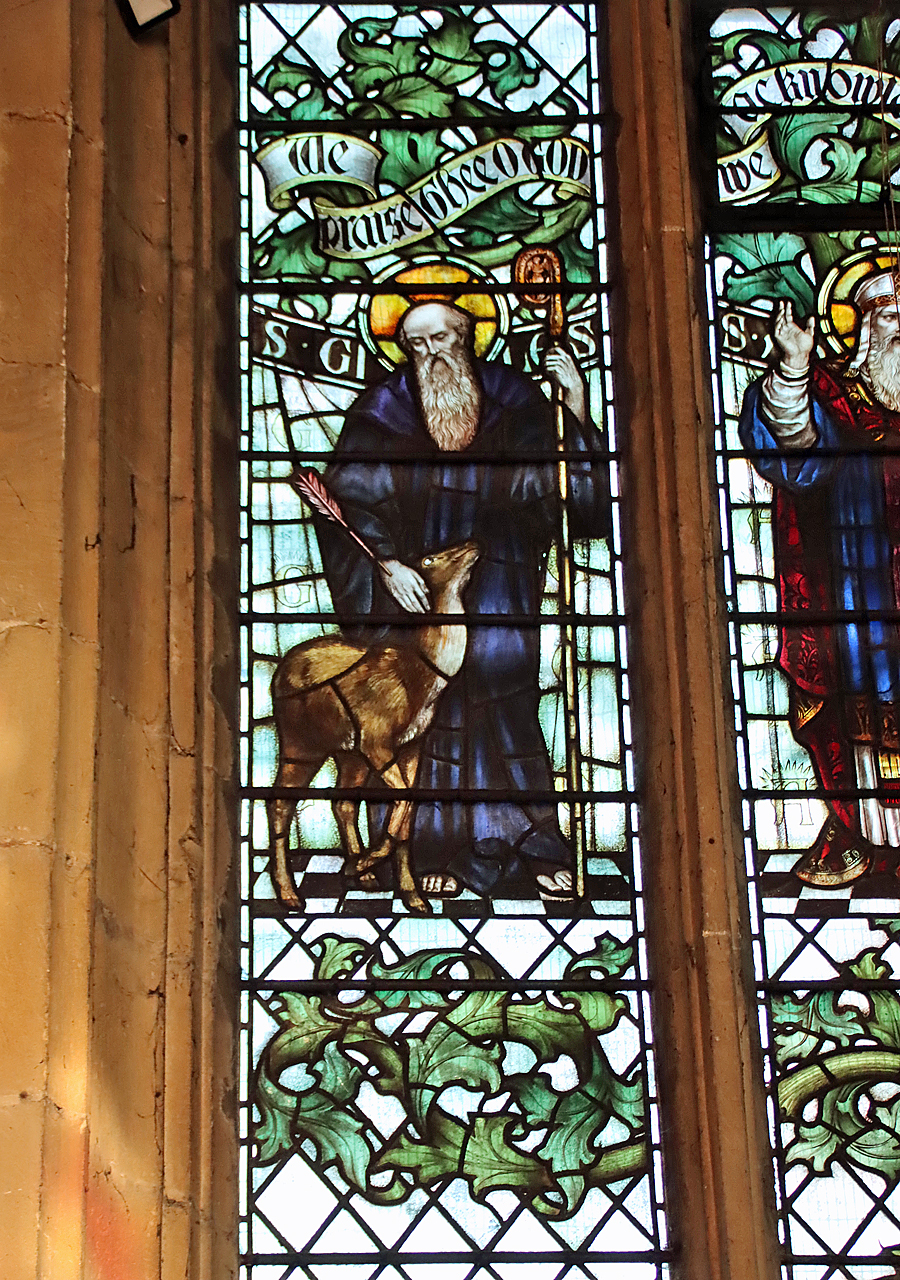

St Giles became the patron saint of the sick (particularly cripples and lepers), the poor and nursing mothers. Books like the Legenda ensured that the inspirational story spread across Europe. There are records of around 162 churches dedicated to him in England and at least 24 hospitals bearing his name. A leper hospital dedicated to him was located in Chester beyond the Northgate. He can be identified by his main symbols, a deer, an arrow, and sometimes an abbot’s staff. His feast day is annually on September 1st.

St Silyn is far more elusive, although sometimes associated with St Tysilio, a Welsh monastic saint of the 7th century (broadly contemporary with St Winefrede of Holywell), whose cult was centred in Powys.

xxx

Medieval Wrexham

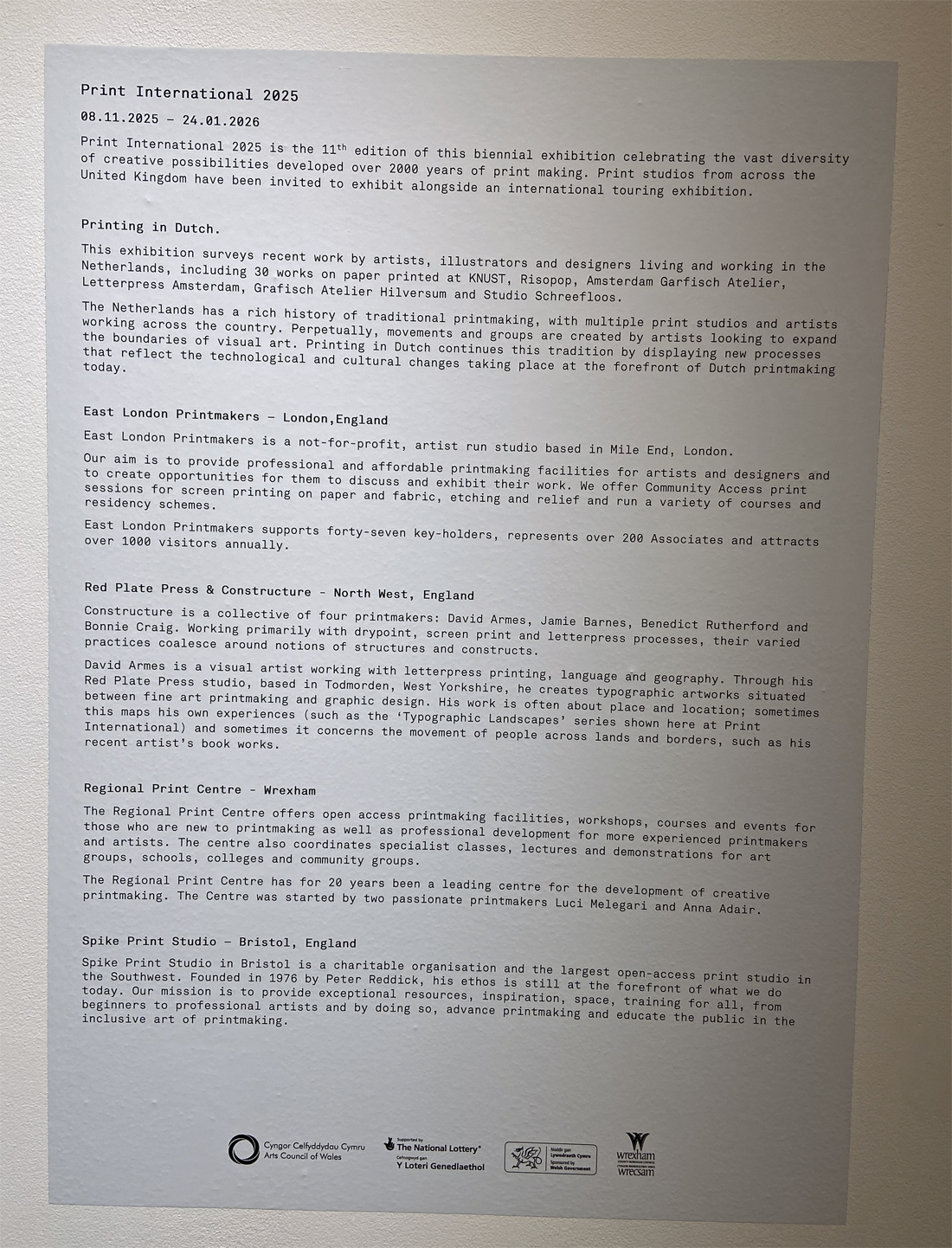

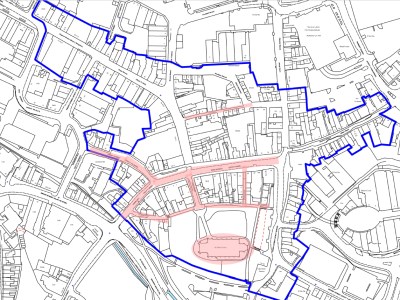

Wrexham Town Centre Conservation Area Character Assessment and Management Plan map 2009, with my annotations in pink to show the Parish Church of St Giles and roads that the report states were laid down during the medieval period

St Giles is a vast edifice, the visible architecture built mainly in the 15th and 16th century to house a large congregation in style, something that required a considerable investment in its basic form, its ornamental embellishments and its furnishings. Today the church is surrounded by a mixture of urban buildings from different periods. Throughout Wrexham Georgian and Victorian buildings speak of 18th and 19th century confidence, but unlike Chester, where there are plenty of echoes of its medieval and Tudor past, there are scarcely any obvious indications of a medieval heritage. However, a bit of hunting around in local resources (with thanks to the local history section at Wrexham’s public library) produced some useful information about the medieval townscape of Wrexham.

The earliest sign of a settlement in the immediate area is a motte and bailey castle prior to 1161 located 1 km away at Erddig, called “de Wristlesham,” which must have supported a settlement, although it is now known exactly where the accompanying settlement was located. The predecessor of today’s Wrexham was certainly founded by 1220 because it is at this time that Bishop Reyner of St Asaph allocated half of Wrexham’s income to Valle Crucis Abbey in Llangollen (established 1201), with the other half granted to them in 1227 by Bishop Abraham, also of St Asaph. Prince Madog ap Gruffyd of Powys Fadog, the founder of Valle Crucis, added to its coffers in 1247 when he granted the abbey the tithes (a type of religious tax earned by parish churches) of the parish church of Wrexham, sealing the link between the town and the abbey, even beyond Henry VIII’s suppression of the monasteries. By accepting the tithes, the abbey also accepted certain responsibilities to the church, including appointing its clergy and maintaining the chancel.

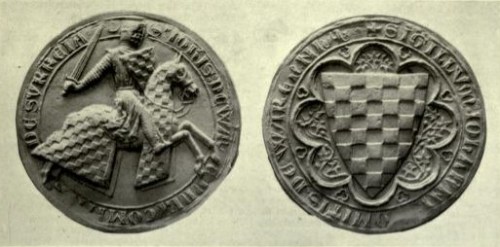

Seal of John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey. Source: Wikipedia

Wrexham’s history started to take a more recognizable and politically stable shape following Edward I’s shake-up of Wales after the defeat of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd (Llywelyn the Last), his brother Daffyd and their supporters in 1282-3. This destroyed the 13th century challenge to England’s control in northeast Wales. As part of Edward’s plan to bring northeast Wales under English control, Wrexham became the centre of lordship of Bromfield and Yale within the cantref (administrative district) of Maelor under the lordship of John de Warenne, 6th earl of Surrey (best known for building the castle at Holt on the River Dee to the north, completed c.1315). It is recorded that in 1316 Wrexham was spelled Wrightlesham, and was based in the current location with an accompanying church. By this time there was a thriving community of 44 tenants who held 52 tenements, with several markets. In 1330 the church tower fell during a storm, which must have created quite an impression on the town!

The Grade 2* listed 7-9 Church Street, thought to date to the 1500s. Timber-framed, originally thatched, and possibly a single storey mid-medieval hall house, the oldest remaining buildings in Wrexham to which alterations were later made. A floor was added in the 17th century, and it was renovated in the 1990s

The growing importance of Wrexham was confirmed by the king’s grant of a market charter in 1391, permitting it to hold a weekly regional market and annual fair, becoming a focal point for trade and encouraging the growth of local manufacturing and service industries. Based initially on agricultural activities, with land suitable for some cultivation and a lot of livestock herding, the town’s commercial status was given a boost in the 15th century with the development of coal mining, initially for local consumption, and iron production. A leather tanning industry, together with all its associated skills, was also well established.

As well as almshouses at Llangollen Abad, a number of documents also refer to the abbey having almshouses in Wrexham, although their original location is not mentioned. They were destroyed in 1589 by inhabitants of Wrexham, angry by the appropriation of all of the abbey’s properties and financial resources by incomers, and the buildings were converted to raw materials (brick, tile, wood etc) that could be carried off for use elsewhere.

The revolt of Owain Glyndŵr in the first decade of the 15th century, unlike other unluckier towns in Wales, had no direct impact on Wrexham in terms of attacks and damage to property. Its effect would have been felt, however, in terms of the disruption to economic activities, transport and communications. In rural areas the attacks, resulting in loss of resources and income in some areas, would have caused great hardship, and would have led to the fluctuating availability of goods in the Wrexham markets. Ripples of uncertainty would also have felt throughout the town, as the potential impacts of Glyndŵyr’s activities and the future of Wales, as well as concerns about the immediate fate of the town, would have been extensively debated.

Unlike Chester, the medieval and Tudor past of which is writ large on the cityscape, Wrexham’s early past is architecturally elusive, most of it demolished and replaced by much more recent buildings, roads and the former Ellesmere-Wrexham railway, its fugitive remnants hidden in nooks and crannies. The main indicator of medieval Wrexham today is the arrangement of roads that once fanned out in all directions in a radial pattern from the church itself. Original medieval roads, lanes and alleyways in Wrexham were very narrow, mainly straight, and were characterized by narrow, low buildings. According to the Wrexham Town Centre Conservation Area Character Assessment and Management Plan report, the wider roads were those where market stalls lined the sides, such as the High Street. Other medieval roads and lanes are Abbot Street, College Street, Temple Row, Town Hill, and The Ney. In 1643 around one quarter of the part of the town that was clustered around the market area was burned down. It was quickly rebuilt, reflecting both the importance of the town and the funds available locally in the Stuart period, but the fire almost certainly took with it a number of medieval buildings.xxx

The former Wrexham and Ellesmere Railway of 1895. The carriage in the distance next to a white building shows the Central Station (moved in 1998) and beyond is the church of St Giles, with one branch of the railway running to its south. This section of railway partially closed in 1962 and completely closed in 1981. Source: Wikipedia

In spite of the 1643 fire, the 19th century railway that tore up part of the town, and the unsympathetic redevelopments of the 1960s, there are two complete medieval buildings remaining, although you need a sharp eye to spot them, on Church Street (no.s 7-9) and Town Hill (5, 7 and 9). The Golden Lion pub at the north of the High Street originated in the 16th century. Otherwise, remnants of medieval timber frames can still be found within some later buildings, the footprints of long thin burgess plots and footprints of shopfronts with yards, where only the yards remain. Beneath the current ground level there is still potential for learning more about the medieval period: “The medieval core remains a highly sensitive archaeological area. There is a strong likelihood that remnants of buildings and deposits may be found in the excavation of land, provided this has not been destroyed by later structures” (Wrexham Town Centre Conservation Area Character Assessment and Management Plan 2009, p.9).

Railway passing just south of St Giles through what was once the southern extent of the churchyard. Source: Facebook

A brief history

The Gothic church

The parish church of St Giles in the first half of the 19th century by W. Crane. Source: medievalheritage.eu

As mentioned above, the earliest reference to a parish church in Wrexham was in 1220 when the Bishop of St Asaph granted the monks of Valle Crucis Cistercian Abbey in Llangollen half of the income of Wrexham. In 1247, the Prince of Powys, Madoc ap Gruffydd, granted the monks of Valle Crucis the tithes of the parish church of Wrexham. It is probably from this earliest period that the splendid stone effigy of Cyneurig ap Hywel dates. The full-sized depiction of the Welsh knight shows him with long hair, no helmet, but with a sword in his left hand and shield over his body, showing a lion rampant and the legend in Latin “here lies Cynerig ap Hywell.” It was found in the churchyard and moved indoors for its protection, now lying at the west end of the north aisle in the war memorial chapel.

14th century corbel sculpture with a mermaid holding a mirror and comb facing into the nave on the north face of the south arcade (left as you walk down towards the chancel)

In 1330 on St Catherine’s feast day the church tower fell during a severe storm. It was widely believed that this was because the weekly market took place on a Sunday, angering either St Catherine or God, or both; subsequently the market was held instead on a Thursday. The original church was largely rebuilt with an emphasis on the gothic Decorated style. The arcades with their very fine lancet-shaped arches and octagonal pillars date from this rebuild. Although some of the sculpted corbels were provided with their sculptural elements in the 19th century, others are thought to be 14th century, including a man with toothache in the north aisle, and a mermaid with mirror and comb in the south aisle (the latter very reminiscent of a medieval misericord in St Oswald’s church in Malpas). Some of the mason’s marks within the church are thought to belong to this period. There was no stone tower and no chancel, but it is thought that by the end of the 14th century a wooden bell tower had been added at the west end on the site of the fallen stone tower.

The east end of the church with the former east end window arch now serving as the chancel arch (see bits of tracery from the old window) and the Doom painting above. The three-sectioned apse lies beyond, behind an enormous stone reredos.The pulpit at left dates to the 19th century. The raised semi-circular dais in the foreground is modern.

In the mid 15th century, either in 1457 or 1463, the 14th century church went up in flames, and yet again the church had to be largely rebuilt, based on the footprint of the 14th century church, but adopting the new fashion for the Perpendicular. A new roof was added. Only a few elements of the Decorated style, such as the arcades, survived. Likewise, the decorated corbels that supported the former roof, although they no longer had a practical function, were left in situ.

In 1506 a new set of works took place to transform the church into the structure seen today. The roof was again replaced, this time with a wooden camber beam ceiling, supported on corbels featuring armorial shields. Sixteen brightly painted angels playing musical instruments or singing look down from the roof, and the glorious Doom painting was added above the chancel at this time (about which more below), with a small red devil’s face on the roof in front of it. The north porch and a new chancel were added, and the new tower was completed in 1525, extending the length of the church and giving it a magnificent presence in the landscape. The extension of the chancel was achieved by taking out the former east window, which now forms the chancel arch, with part of the former window’s tracery still clearly visible. The Perpendicular is usually a less lively version of the gothic aesthetic than the previous Decorated, and can be rather regimented and severe, but the sheer number of pinnacles, crockets, battlements, canopies, statues, sculpted corbels, bosses, angels, gargoyles and grotesques, both inside and out, but particularly the famous sculpted elements on the tower, provide the church with real energy. The font (see further down the page) was certainly present in the 16th century, but its date is unknown. It was lost during the Civil War, but was remarkably returned to the church in 1843.

The legs of Man, associated with the Stanley family. South aisle, arcade. Possible mason’s mark in the chiselled block at top right.

Although previous rebuilds had been the result of storm and fire damage, this time the 1506 works seem to have been the result of an investment in status, suggested by the proliferation of Tudor imagery throughout the church, including the Tudor rose and portcullis (associated with Henry VII) and the symbolism associated with the Stanley family (such as the legs of the Isle of Man) who are thought to have invested in a number of religious buildings in the area, including the parish churches at Gresford, Holt and Mold, as well as the superb chapel at the shrine of St Winefrede in Holywell. The devout Margaret de Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, who married Thomas Stanley in 1482 is often credited with much of this work, but it is not always clear from documentation what form her or her family’s influence or investment took. If the investment was not made exclusively by the Stanelys, it remains unknown how the financial injection was sourced and where from.

Decorated spandrel on the 16th century north porch, showing a splendid, if slightly startled-looking lion

In Henry VIII’s Valor Ecclesiasticus of 1535, a valuation of all the monastic holdings in Britain, it is recorded that pilgrim offerings were being made to images in the church of St Giles (a property of Valle Crucis Abbey), amounting to £2.62.8d, which according to the National Archives Currency Converter is around £1029 in today’s money. The entire contribution of St Giles to the abbey was recorded as £14 2s 8d (c.£6000 today) for temporalities (secular income such as farms, mills, tenant farmers, mines and quarries and sundry rural and urban buildings that could secure rents), and £54 16s 8d (c.£23,000) for spiritualities (income derived from religious sources such as church tithes and other revenue, pilgrim donations, oblations, and chantries). It also showed how the abbey short-changed the vicars of its appropriated churches. The abbot claimed £50 9s 2d (c.£21,000) from Wrexham’s parish church, but the vicar only earned £19 9s 8d (c.£8209 – c.39%).

One of the interesting questions regarding the early Tudor period is what happened after Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. The church and other Wrexham resources had become one of many possessions of Valle Crucis Abbey (founded 1201) during the 13th century, but after Valle Crucis had been dissolved, probably in January 1537, the abbey itself was granted by the king to a Yorkshireman, Sir William Pickering, causing significant local resentment from local landowners who had their own designs on the former abbatial property and its incomes. Although some of the abbey’s land and properties were dispensed of, and most of its building materials stripped down and the church dismantled, many properties that provided incomes were retained by Sir William, including revenues from Wrexham’s parish church. The income from St Giles for the year 1538-9 (in Appendix II of Derrick Pratt’s book on the subject of the dissolution of Valle Crucis) earned him £50.00 per annum (c.£21,000, according to the National Archives Currency Converter), one of five ecclesiastical incomes that he enjoyed, as well as those from secular properties. Quite what this meant for how St Giles was administered, including who was now responsible for appointing the clergy, and how and what they were paid is not clear.

One of the interesting questions regarding the early Tudor period is what happened after Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. The church and other Wrexham resources had become one of many possessions of Valle Crucis Abbey (founded 1201) during the 13th century, but after Valle Crucis had been dissolved, probably in January 1537, the abbey itself was granted by the king to a Yorkshireman, Sir William Pickering, causing significant local resentment from local landowners who had their own designs on the former abbatial property and its incomes. Although some of the abbey’s land and properties were dispensed of, and most of its building materials stripped down and the church dismantled, many properties that provided incomes were retained by Sir William, including revenues from Wrexham’s parish church. The income from St Giles for the year 1538-9 (in Appendix II of Derrick Pratt’s book on the subject of the dissolution of Valle Crucis) earned him £50.00 per annum (c.£21,000, according to the National Archives Currency Converter), one of five ecclesiastical incomes that he enjoyed, as well as those from secular properties. Quite what this meant for how St Giles was administered, including who was now responsible for appointing the clergy, and how and what they were paid is not clear.

The 17th century and Civil War

1524 brass lectern with an eagle on a sphere supported on an ornate stand, with four lion’s feet at its base, which went on to support an original 1601 copy of the King James Bible. It is a surprising survivor of the Protestant attack on the church

The 17th century was a tumultuous period for the churches of England and the borders. Many were targetted by Puritans determined to eliminate even a hint of pre-Reformation papism, finery and ritual. The Puritans, suspicious of any rituals and richly ornate ceremonial objects and vestments that echoed elaborate Catholic practices, set about destroying the ornate and the rich. Worship per se was not discouraged, but the Puritans demanded a purer and more modest relationship with God that reflected honesty and humility rather than wealth, artworks and ostentation.

The church of St Giles did not escape Puritan notice, although the damage could have been much worse. The organ was destroyed in 1643, the font was removed and a tomb was opened. John Rowland Phillips gives a vivid description in his Memoirs of the Civil War in Wales and the Marches, describing Sir William Brereton’s advance into Wales: “In Wrexham they broke in pieces the best pair of organs in the King’s dominions, the lead pipes of which were converted into bullets.” Phillips seems to feel that they should be congratulated for their restraint in not pillaging homes “purloining nothing save from churches and damaging nothing save what to them appeared superstitious and idolatrous.” (p.181). It was actually the Bishop of St Asaph who, in 1662, ordered the removal of the rood-loft from the church. Rood lofts were particularly targeted because they segregated the public from religious activities, instead of allowing them uninterrupted access to the clergy and their lessons. The sense of mystery and ritual was being placed by unambiguous preaching and sermons.

It is thought that after the destruction of the rood screen, the chancel was segregated from the nave and used for secular, possibly administrative activities, whilst the nave was used by the vicar and congregations. A surprising survivor of the Puritan visits is the 1524 brass lectern with an eagle on a sphere supported on an ornate stand, with four lion’s feet at its base, which went on to support an original 1601 copy of the King James Bible. Presbyterian preachers were appointed to St Giles as vicars.

The 18th Century

In the early 18th century, Wrexham had not moved particularly far, in terms of its economic structures, from the medieval period, still based on agriculture, leather tanning and a nail-making industry, with some coal and lead mining. However the area benefitted from the expansion of the Industrial Revolution, and in the late 1700s John “Iron Mad” Wilkinson opened the Bersham iron foundry in 1762 and the Brymbo smelting plant in 1793. Even so, by 1801, Wrexham’s population was still only some 2,575 inhabitants, less than half the size of the population in 1841, suggesting that a slow start in the direction of industrialization soon gained traction.

The church benefited from the generosity of Elihu Yale of Plas Grono, best known for his investments in Yale University in Connecticut, today one of the most prestigious American universities, founded in 1701. His contributions to St Giles were a gallery at the eastern end of the nave in 1707, moved to the west end in 1718, but removed in 1779. Also in 1707 he is thought to have paid for the installation of the low wrought iron screen that marks the entrance to the chancel, by Robert Davies of Croesfoel. A Royal Arms of Queen Anne was added at his expense to the north porch in 1718. Finally, Yale paid for a new organ to be added in 1779, to replace the one destroyed in 1643. The chest tomb of Elihu Yale is still located at the west end of the church.

A magnificent addition to the church was the wrought iron gateway and flanking railings by Robert Davies (about which more below), who is also thought to have made the screen to the chancel. They were installed in 1720 and attached to buildings on either side of Church Street, moved to their present position a century later in 1820.

In 1747 the most impressive of the church’s memorials was added. Sculpted by Louis Francois Roubiliac, it commemorated the life of Mary Myddelton (on which more later). In 1793 the pressure on the churchyard, where all Anglican burials were interred, was relieved when a new dedicated cemetery was laid out on Ruthin Road.

The 19th and 20th-21st Centuries – restoration and adaptation

The 18th and 19th centuries marked considerable growth in Wrexham. By 1841 the population had reached 5,854 and by 1881 it was 10,903. This was a good period for the church, with the presence of large congregations ensuring its continued relevance and ongoing maintenance. The presence in Wrexham of new wealth founded on industry, now including brewing, translated into investment in the town’s infrastructure and architecture, as well as the church’s structure and features. Fortunately in the case of the church, much of the work carried out was sympathetic to the medieval building. In 1809, the Grade 2 listed octagonal sundial was added to the churchyard, a gift from Edward Ravenscroft. In 1822 new box pews were added so that the wealthy could purchase their own private places for attending services. In the same year a new south porch was added. Sadly for the medieval and later remnants of historic Wrexham, the railway ploughed through much of the town south of the church, taking most of the churchyard with it, opening in 1895.

19th century statue of Moses with the tablets listing the 10 Commandments standing on a corbel that has a portcullis emblem, one of the armorial symbols of the Stanley family in the Tudor period

A major programme of church restoration was carried out, lead by Benjamin Ferrey in 1866-7, during which a wall painting of the crucifix was found in the north porch. The family box pews installed in 1822 were removed in 1867 to make way for open pews and the giant statues on the arcades of St Augustine, St Paul and Moses were added in the same year, as was the stone pulpit gifted to the church by Willow Brewery proprietor Peter Walker, twice mayor of Wrexham). The c. 1747 Roubiliac memorial to Mary Myddelton (more below) was moved to the north aisle in the same year, where it remains. The 14th century corbels were fitted with new sculptural elements at the same time, although the mermaid holding a mirror in the south aisle and the man with toothache in the north aisle are almost certainly original. The present organ, with its pipes colourfully decorated, was installed in 1894. A ceiling boss showing St Giles was added to the north porch some time later, in 1901. The Robert Davies gates were renovated at around the same time. The south aisle stained glass was installed sometime in the 19th century, five of them by well known stained glass designer Charles Eamer Kempe. Most of the south aisle is now screened off at least some of the time for community activities, so it may not always be possible to see the windows.

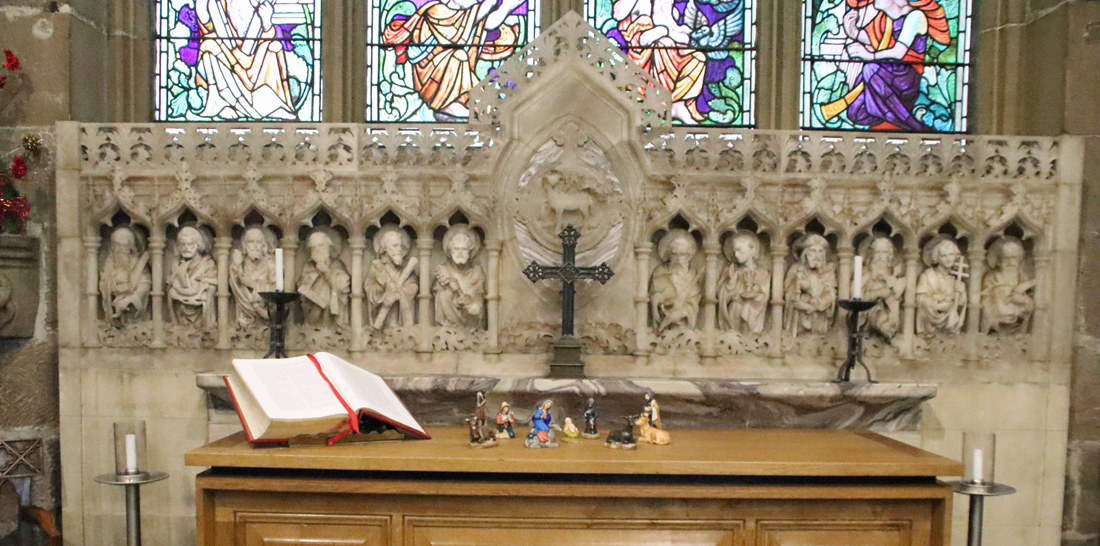

The 1914 refurbishment of the chapel included the installation of the enormous alabaster reredos by Sir Thomas Graham Jackson showing four scenes from the life of Christ, and the three stained glass windows in the apse designed by Jackson and made by James Powell and Son. The central window depicts the Jesse Tree (substantially hidden by the reredos) and on the left St Giles and the doe is also represented.

The charmingly decorated organ, built in 1894, was restored in 1984. The next major work at the church was the re-ordering of the church in 2012, which created new facilities for administration, the congregation and visitors, including kitchen, toilets and a meeting room, the conversion of most of the south aisle into a screened-off community space and the re-positioning of the altar, pews and the removal of choir stalls so that the available space could be used more efficiently.

xxx

The uplifting Angel Festival at St Giles. Source: The Church in Wales

The church is still going strong today, with services, baptisms, weddings and funerals, as well as ongoing community activities, such as community lunches and regular events such as heritage talks, art exhibitions, music concerts and Christmas and other seasonal celebrations. Following the Coronavirus pandemic of 2019 and the losses experienced during the lockdowns, the church organized a remarkable commemorative event, with the making of over 6000 fabric and paper angels, each representing a death directly caused by Covid, all strung across the church. The photographs from that time show that it was a remarkable sight, a touching commemoration of a terrible period that both involved the community and helped to support it. As 2026 is the official celebration of the 1876 Year of Wonder, the church is celebrating with a special 1876 Liturgy Service on St. David’s Day on 1st March, together with a celebratory bell-ringing performance using the innovative Ellacombe mechanism that was installed in the bell tower in 1876.

Highlights of a visit to the church

The church of St Giles approached from Church Street, with the white medieval buildings, nos 7-9 Church Street on the right.

The leaflet and guide book, both available in the church, will give you their recommended features. I’ve taken just a handful that struck me particularly for these highlights.

The main approach to the church is via Church Street. This is recommended, as not only can you see the medieval buildings, numbers 7-9, on your right as you approach the church, but you enter the churchyard via the magnificently ornate gate and flanking railings painted in black and gold. These were made by Robert Davies of Croesfoel forge near the local source of iron at Bersham, and were fitted to buildings on opposite sides of Church Street in 1720, only being moved to their present position in 1820. The Davies brothers are probably best known for the stunning gates at Chirk Castle. On the way in to the churchyard of St Giles the legend over the gateway reads O GO YOUR WAY INTO THESE GATES WITH THANKSGIVING AND INTO HIS COURTS WITH PRAISE,” and on the way out, the optimistic “GO IN PEACE AND SIN NO MORE.”

On the exterior of the church, there is a plethora of masonry features to admire – almost too many to get to grips with. The 16th century north porch, through which you enter the church, is two-storey and features the Virgin Mary over the entrance. Today’s 41m tall tower replaced the original tower that collapsed during a storm in 1330, and was built in the early 16th century. It is impressively elaborate with statues in niches standing on sculptural corbels and topped with ornamented canopies, its top ornamented with plenty of pinnacles and crockets. The aisles of the main building, feature huge windows with flattened arches along each side, topped with battlements and an army of gargoyles. The exception, pointed out to me by one of the church volunteers (sorry – I forgot to as your name!) is a lancet-shaped arched window at the west end of the south aisle, which looks like the earlier Decorated arches that make up the interior arcades. It is the only one of its type along the aisles, sitting to the east of the chancel, and is not visible from the interior where it is blocked by the organ.

On the exterior of the church, there is a plethora of masonry features to admire – almost too many to get to grips with. The 16th century north porch, through which you enter the church, is two-storey and features the Virgin Mary over the entrance. Today’s 41m tall tower replaced the original tower that collapsed during a storm in 1330, and was built in the early 16th century. It is impressively elaborate with statues in niches standing on sculptural corbels and topped with ornamented canopies, its top ornamented with plenty of pinnacles and crockets. The aisles of the main building, feature huge windows with flattened arches along each side, topped with battlements and an army of gargoyles. The exception, pointed out to me by one of the church volunteers (sorry – I forgot to as your name!) is a lancet-shaped arched window at the west end of the south aisle, which looks like the earlier Decorated arches that make up the interior arcades. It is the only one of its type along the aisles, sitting to the east of the chancel, and is not visible from the interior where it is blocked by the organ.

Continuing to walk to the east, the three apse windows each feature elegant ogee frames around the arched windows. There is not much of the churchyard left, but some fine chest tombs are a reminder that this was once the burial place for all Anglican burials in Wrexham before the 1793 cemetery open on Ruthin Road.

The two-storey north porch, through which you enter the church itself, was added in the early 1500s, and on the exterior has a niche with a sculpture of Mary and child. On entering, you will see a vaulted roof with a number of ceiling bosses, the central of which, dating to 1901 is St Giles. Straight ahead, but very difficult to make out, there was a painting on the wall, thought to have been of a crucifix, but sadly only a few black lines remain and the original subject matter is impossible to make out.

xxx

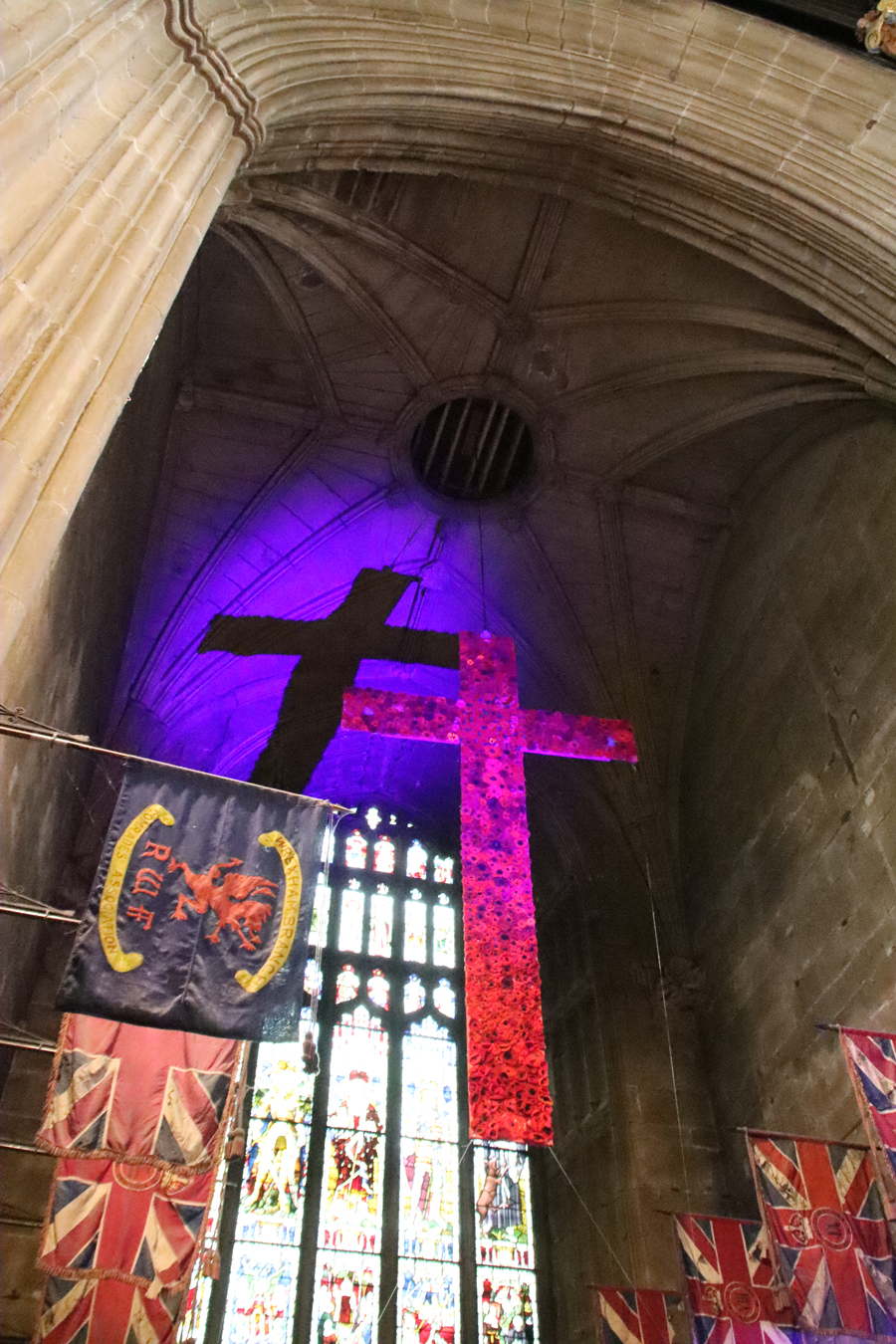

The entire north aisle (left as you enter the church), entered via a wooden screen at its west end, is designated as a chapel lined with marvellously colourful flags (regimental colours) belonging to the RWF.

A window in the north aisle, dating to 1989, is a lively celebration of the Royal Welch Fusiliers by Joseph Nuttgens, showing different uniforms that have been used by the regiment between 1689 to 1989.

The end of the aisle, as you approach the chancel end, note the effigy of Cynerig ap Hywel, mentioned above. The end of the aisle is now the Wrexham War Memorial Chapel, but was originally a chapel dedicated to St Catherine, whose image appears on the east side of the tower. The alabaster reredos shows the twelve apostles, with the 19th century window above showing the Sermon on the Mount. Note the 19th century ceiling decorated with colourful bosses. Although it was built during the 1847 restoration to resemble the roof in the main nave, the ceiling bosses all represent local organizations, some of which are still operating today.

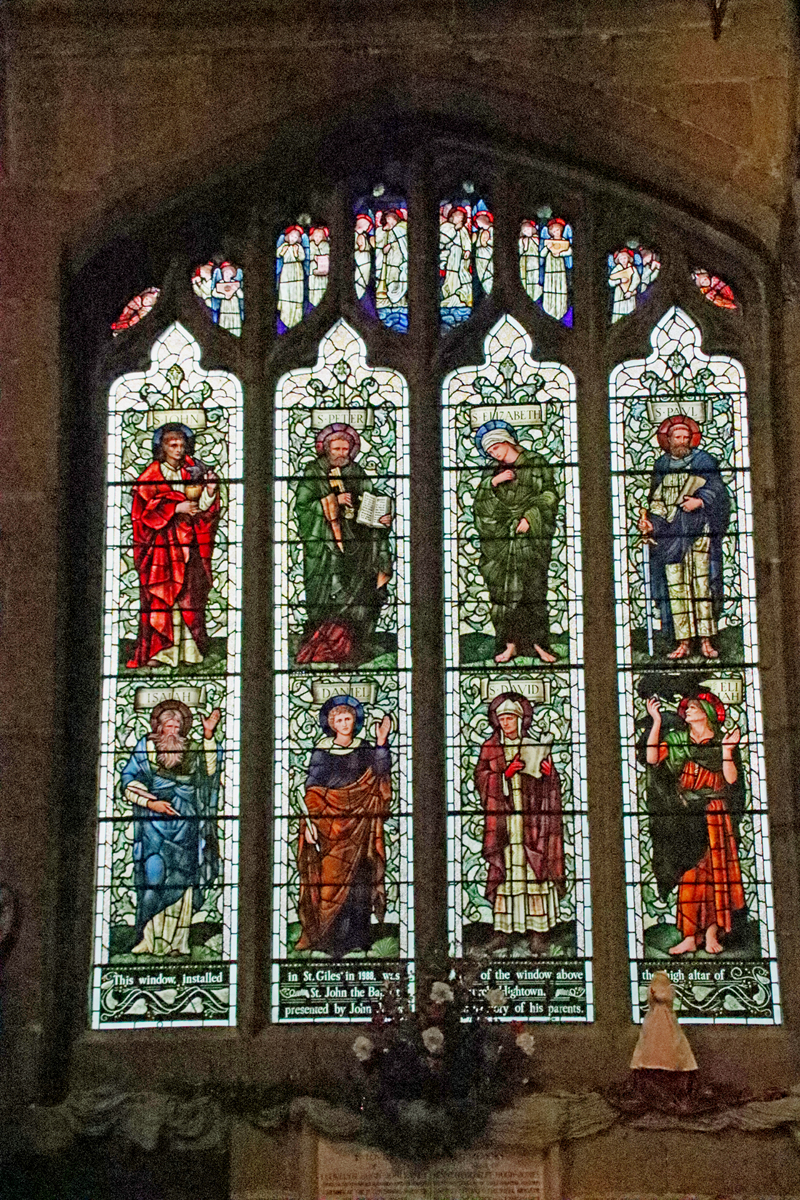

Inside, as you begin to walk down the north aisle note the 1910 Edward Burne-Jones stained glass on the left, which was moved from St John the Baptist Church in Hightown in 1988, prior to its demolition, originally presented to St John’s by the owner of the Island Green Brewery in memory of his parents. With its Pre-Raphaelite palette of bright, rich colours and the almost androgynous holy faces, it is a particularly fine piece, showing eight saints from both Old and New Testaments. all on the background of green foliage (John, Peter, Elizabeth, Paul, Isiah, Daniel, David and Elijah). The lights at the very top are filled with angels with crimson halos and blue wings. The inscription at the base, with Art Nouveau foliage wending its way along the bottom, records the date of the window being moved, and the reason for its original installation. It is easy to walk past stained glass windows without distinguishing between them, particularly in a church where there is so much of it, but there are some fine examples in the church of St Giles that are worth noting. See a complete set of the St Giles stained glass on the Stained Glass in Wales website.

Inside, as you begin to walk down the north aisle note the 1910 Edward Burne-Jones stained glass on the left, which was moved from St John the Baptist Church in Hightown in 1988, prior to its demolition, originally presented to St John’s by the owner of the Island Green Brewery in memory of his parents. With its Pre-Raphaelite palette of bright, rich colours and the almost androgynous holy faces, it is a particularly fine piece, showing eight saints from both Old and New Testaments. all on the background of green foliage (John, Peter, Elizabeth, Paul, Isiah, Daniel, David and Elijah). The lights at the very top are filled with angels with crimson halos and blue wings. The inscription at the base, with Art Nouveau foliage wending its way along the bottom, records the date of the window being moved, and the reason for its original installation. It is easy to walk past stained glass windows without distinguishing between them, particularly in a church where there is so much of it, but there are some fine examples in the church of St Giles that are worth noting. See a complete set of the St Giles stained glass on the Stained Glass in Wales website.

The north aisle also boasts a memorial sculpture by Louis François Roubiliac to Mary Myddleton (1688-1747) of the 17th century Croesnewydd Hall (still standing next to the Wrexham Maelor hospital). Mary Myddelton was the daughter of Sir Richard Myddelton of Chirk Castle. I normally don’t pay attention to memorials, as they are very rarely designed to blend in with the architecture and are often dreadful carbuncles on the face of beautiful buildings (Westminster Abbey is a prime example), but this one does require recognition, although to modern tastes it is extravagantly ornate and somewhat melodramatic. It is a rather good contrast to the Doom painting over the chancel arch, showing a completely different style of interpretation of the same foretold event. Roubiliac (1702-1762) was a highly regarded sculptor in his French homeland, coming second for sculpture in the Académie Royale’s Prix de Rome. He moved to London in 1730, where he became very fashionable. The subject shows the Day of Judgement. An angel in a cloud blows his trumpet to summon the dead, and Mary Myddelton, discarding her shroud, climbs from her black stone tomb, which bears an indistinct inscription. Behind her is a palm frond, signifying the Christian promise of everlasting life triumphing over death. The toppling pillar or obelisk in the background represents diveine judgement and the final end of the material world.

It has been suggested that this corbel represents Thomas Stanley, but quite why Stanley should have the ears of a donkey remains unexplained

Unlike most of the church, which reflects the late medieval fashion for the rather severe and highly linear Perpendicular style of gothic architectural design with flattened arches, the parallel arcades that separate the nave from the aisles were built in the earlier Decorative style, with elegant lancet-shaped arches supported on strong octagonal piers (columns). The livelier and more expressive Decorative style is also found in some of the corbel sculptures found throughout the church (bearing in mind that some of them are 19th century, built in the same style). Original medieval examples include a man with toothache (north aisle) and a mermaid holding a mirror (north arcade, facing into the nave, photo further up this post), a man with donkey ears (behind the pulpit) and a lady, possibly Margaret de Beaufort (on the east side of the chancel arch, at the very top). The 19th century imitations have taken gothic examples as their models and are an imaginative collection that offer an insight into how the late medieval church originally looked. In the 18th century the arcades were fitted with galleries, which somewhat minimized the elegant impact of the arcades, but were a curiosity in their own right. They were removed in the early 19th century.

The 16th century camber beam roof features ornamental bosses and 16 splendid musician angels, each holding a musical instrument or singing. In his guide to the church, Williams lists the instruments as follows: 10 playing citherns (similar to lutes), 1 with bagpipes, 1 with a double pipe (shown near the top of this post), 2 playing harps, and 2 playing an unknown instrument. Follow the line of the roof towards the early 16th century chancel, and look at the chancel arch. The arch was part of the wall at the far end of the church prior to the building of the chancel, it and once housed a vast stained glass window. Look at the inner line of the arch (photo below) and you will see the remains of the tracery that once held the stained glass.

The 16th century camber beam roof features ornamental bosses and 16 splendid musician angels, each holding a musical instrument or singing. In his guide to the church, Williams lists the instruments as follows: 10 playing citherns (similar to lutes), 1 with bagpipes, 1 with a double pipe (shown near the top of this post), 2 playing harps, and 2 playing an unknown instrument. Follow the line of the roof towards the early 16th century chancel, and look at the chancel arch. The arch was part of the wall at the far end of the church prior to the building of the chancel, it and once housed a vast stained glass window. Look at the inner line of the arch (photo below) and you will see the remains of the tracery that once held the stained glass.

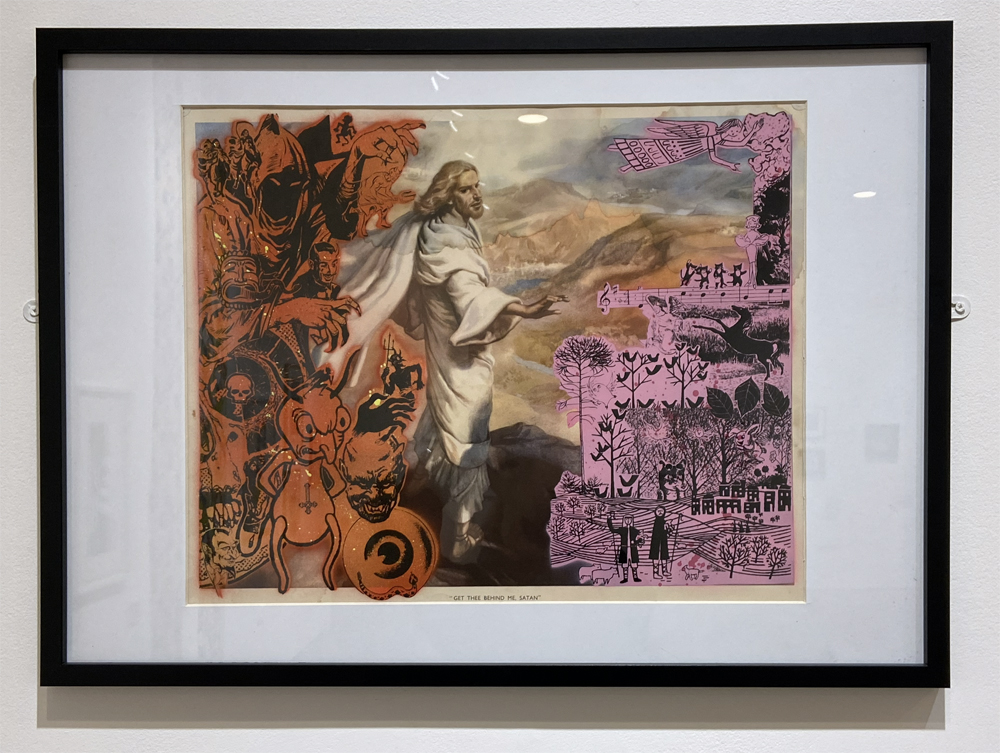

Above the chancel arch is one of the most remarkable features of Welsh church art – the fabulous Doom painting showing the Day of Judgement. It is the most complete example known in Wales, thought to be contemporary with the chancel itself. The central section is much better preserved than those flanking it, suggesting that the central portion may have been covered over at some stage for some time. The clerestory windows were enlarged to cast light onto it and make it more visible to the congregation, to whom the warning of an impending Judgement Day was directed. The central scene is missing its upper register, eliminating Christ’s head and shoulders, but the rest of the scene shows him presiding over figures emerging from coffins, the whole composition highlighted against a background of black merging into dark green. Christ himself is seated on a rainbow, signifying the promise of redemption, and wears a red robe decorated with floral motifs. Wounds on his hands and feet and in his side are visible. To his right (the onlooker’s left) is the Virgin Mary in a cloak of ermine with her breasts exposed to indicate her role as mother. On the opposite side is St John the Baptist in an animal skin, with the head still attached. Either side of Christ are saints in robes of yellow or red, and beyond them angels with the symbols of the Passion – nails, pincers and lances. Below this hierarchy of the divine are small naked figures rising from their graves, some in shrouds. A mitred bishop and a crowned monarch make it abundantly clear that no-one is spared Judgement. Hell is at the lower right, further down the side of the arch, with rows of barely visible figures and red flames licking upwards.

Above the chancel arch is one of the most remarkable features of Welsh church art – the fabulous Doom painting showing the Day of Judgement. It is the most complete example known in Wales, thought to be contemporary with the chancel itself. The central section is much better preserved than those flanking it, suggesting that the central portion may have been covered over at some stage for some time. The clerestory windows were enlarged to cast light onto it and make it more visible to the congregation, to whom the warning of an impending Judgement Day was directed. The central scene is missing its upper register, eliminating Christ’s head and shoulders, but the rest of the scene shows him presiding over figures emerging from coffins, the whole composition highlighted against a background of black merging into dark green. Christ himself is seated on a rainbow, signifying the promise of redemption, and wears a red robe decorated with floral motifs. Wounds on his hands and feet and in his side are visible. To his right (the onlooker’s left) is the Virgin Mary in a cloak of ermine with her breasts exposed to indicate her role as mother. On the opposite side is St John the Baptist in an animal skin, with the head still attached. Either side of Christ are saints in robes of yellow or red, and beyond them angels with the symbols of the Passion – nails, pincers and lances. Below this hierarchy of the divine are small naked figures rising from their graves, some in shrouds. A mitred bishop and a crowned monarch make it abundantly clear that no-one is spared Judgement. Hell is at the lower right, further down the side of the arch, with rows of barely visible figures and red flames licking upwards.

The Doom painting is flanked by two wooden painted angels, with another immediately above. Just before them is a small, bright red feature that looks like a conventional ceiling boss on the roof. If you have binoculars or a long lens you will find yourself looking the devil in the face.

The Doom painting is flanked by two wooden painted angels, with another immediately above. Just before them is a small, bright red feature that looks like a conventional ceiling boss on the roof. If you have binoculars or a long lens you will find yourself looking the devil in the face.

Within the chancel itself, with its triple-sided apse, is a very fine triple sedilia, for the clergy officiating over services, consisting of three recesses canopied arches set into the northeast wall of the chancel, where the clergy sat during services. Above the canopies are highly ornamented panels between the pinnacles. A piscina was sometimes positioned next to the sedilia, but in St Giles this remained in the nave and is now concealed behind the organ.

xxx

Don’t forget to look at the baptismal font in the ante-nave on your way back towards the tower. It is octagonal, with a different motif on every face, and is very fine. Its date is uncertain, but it was known to have been one of the fittings of the church in the 16th century. It was lost during the Civil War, but was rediscovered in the early 19th century in Little Acton House (since demolished), returning to the church in 1843.

Walking around in the churchyard, keep an eye out underfoot because, as with many churchyards in the area, some of the gravestones have been put into practical use as paving stones.

Final Comments

I have no idea why it took me so long to visit the Parish Church of St Giles in Wrexham, but I am very glad that I have not merely visited, but thoroughly familiarized myself with it over a number of visits, and enjoyed it. As well as architectural magnificence, the church has real heart, and there is an unusual feeling of continuity between past and present. Sadly, the 17th century fire, the 19th century railway and the painful decisions of the authorities during the 1960s have destroyed much of the older town’s heritage, as happened in many towns in England and Wales. However, there remain some fine buildings dating to the 18th and 19th centuries, when the church was well used, providing good hints of what the town must have looked like. Although the medieval town has almost vanished from modern view, the church itself speaks loudly about the importance of Wrexham to northeast Wales from the 13th century onwards. It continues to feel like a living part of the community. A very fine building, and a very fine legacy.

2026 is Wrexham’s commemoration of the 1876 Year of Wonder, with events to showcase Wrexham’s Arts, Culture, Industry and Commerce. As well as marking the four-month long great Art Treasures Exhibition of 1876 and the first National Eisteddfod to be held in Wrexham, the Parish Church of St. Giles is currently celebrating the 300th birthday of their bells, so January 2026 is a good time to talk about the church, and to visit its architectural finery and get a sense of its importance to centuries of community life.

xxx

Visiting Details

The Parish Church of St Giles is very welcoming to visitors. It is heated, very well lit, with friendly volunteers on hand to answer questions, and is open every day to visitors except Sundays when it is confined to those attending services,or during weddings and similar events. There is a small shop selling the guide book (including a 41-point self-guided tour on the back – Williams 2018), postcards and souvenirs. There are digital payment posts for taking card donations, which help to keep the church open and well maintained. Outside, there is a path that enables you to do a full circuit of the church, which is well worth doing so that you can see some of the carvings, big and small, that line the upper levels of the walls and the roof pinnacles.

The Parish Church of St Giles is very welcoming to visitors. It is heated, very well lit, with friendly volunteers on hand to answer questions, and is open every day to visitors except Sundays when it is confined to those attending services,or during weddings and similar events. There is a small shop selling the guide book (including a 41-point self-guided tour on the back – Williams 2018), postcards and souvenirs. There are digital payment posts for taking card donations, which help to keep the church open and well maintained. Outside, there is a path that enables you to do a full circuit of the church, which is well worth doing so that you can see some of the carvings, big and small, that line the upper levels of the walls and the roof pinnacles.

Binoculars are very strongly recommended. There are some superb features to see in the interior including the roof itself, the Doom painting and features just above the arcade level which are very high up and cannot be seen clearly without binoculars or a telephoto lens. Likewise, there are some splendid features on the exterior of the building, and in particular tower, which are not visible without optical assistance.

Small grotesques on the south side of the church. I love the way the drainpipe has been carefully diverted around both the grotesque and the window.

The nearest car parking is behind the church in the St Giles Car Park off Tuttle Street (pay and display) – see fees etc here), for three hours maximum, with a capacity of 69 cars. You can walk out of the car-park straight up a flight of stairs into the churchyard. The car park does fill up quickly, and parking to the north of the church is better for anyone with unwilling legs, to avoid stairs. There is plenty of other parking throughout Wrexham. I often park at the multi-storey car park at Tŷ Pawb on Market Street (What3Words address ///track.lazy.poppy), which is long-term but inexpensive (at least at the time of writing in January 2026) and has elevators (What3Words ///waddled.famed.filer). On entry into the car park the system records your registration number and you need this to pay on return to the car park, so do make sure that you know what it is! The pay point (which is thankfully indoors) is outside the pedestrian entrance to the car park and you have to enter your registration before you pay. I have always found that there is always plenty of room there if other car parks are full.

Sources:

Leaflets available at the church

The Parish Church of St Giles, Wrexham n.d. A Brief Guide to the Church. Leaflet with site plan.

The Parish Church of St Giles, Wrexham n.d. A Brief Guide to the Church. Leaflet with site plan.

(Also available online at https://stgilesparishchurchwrexham.org.uk/index.php/history)

The Parish Church of St Giles, Wrexham n.d. Stained Glass Window Guide. By Dr Malcolm Seaborne 1998

Books, booklets and papers

Ebsworth, David 2023. Wrexham Revealed: A Walking Tour with Tales of the City’s History. Carreg Gwalch

Evans, D.H. 2008. Valle Crucis Abbey. Cadw

Farmer, David 2011 (5th edition). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford University Press

Hubbard, Edward 1986. The Buildings of Wales. Clwyd (Denbighshire and Flintshire). Penguin Books / University of Wales, p.297-302

Palmer, Alfred, N. 1893. A History of the Town of Wrexham. Woodall, Minshall, and Thomas.

https://archive.org/details/historyoftownofw0000palm

Phillips, John Rowland 1874. Memoirs of the Civil War in Wales and the Marches, 1642-1649, vol 1. Longman, Green and Co.

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=U28LAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Pratt, D., 1997. The Dissolution of Valle Crucis Abbey. Bridge Books

Price, G. Vernon 1952. Valle Crucis Abbey. The Brython Press

Suggett, Richard with Anthony J. Parkinson and Jane Rutherfoord 2021. Painted Temples. Wallpaintings and Rood-screens in Welsh Churches, 1200-1800. RCHAMW. (Dual language, English and Welsh)

de Voraigne, Jacobus 1993 (with an introduction by Eamon Duffy 2012) . The Golden Legend. Readings on the Saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton University Press

Williams, D.H., 1984. The Welsh Cistercians. Cyhoeddiadau Sistersiaidd

Williams, W. Alister 2001, revised 2010. The Encyclopaedia of Wrexham. Bridge Books

Williams, W. Alister 2018. The Parish Church of St Giles, Wrexham. Published by the Parish Church of St Giles, Wrexham. The best place to find all the most useful information in one place, with an excellent 41-feature annotated map on the back for those wishing to do a self-guided walk. Available to purchase in the shop at the church

xxx

Websites

Cadw

DE158 – Wrexham Churchyard Ornamental Wrought Iron Gates and Screen

https://cadwpublic-api.azurewebsites.net/reports/sam/FullReport?lang=en&id=309

The Church in Wales

Angel festival for Covid victims attracts thousands. 13th January 2022

https://www.churchinwales.org.uk/en/news-and-events/angel-festival-for-covid-victims-attracts-thousands/

Civic Heritage

Wrexham Gateway, Wrexham. Archaeological Desk-based Assessment. July 2025

https://spawforths.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Archaeological-Assessment-Compressed.pdf

Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust / Heneb

Wrexham Churches Survey: Church of St Giles , Wrexham

https://heneb.org.uk/archive/cpat/Archive/churches/wrexham/106012.htm

Heneb

Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust – Historic Settlement Survey – Wrexham County Borough

https://heneb.org.uk/archive/cpat/ycom/wrexham/wrexham.pdf

Wrexham Churches Survey – Church of St Giles, Wrexham

https://heneb.org.uk/archive/cpat/Archive/churches/wrexham/106012.htm

Historic England

Sundial, Approximately 2 Metres West of Tower of Church of St Giles

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1116496

historypoints.org

St Giles’ Church, Wrexham – audio file recording the bells

https://historypoints.org/index.php?page=st-giles-church-wrexham

Howard Williams Blog – ArchaeoDeath

Where can you visit Wat’s Dyke in Wrexham?

https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2019/01/03/where-can-you-visit-wats-dyke-in-wrexham/

National Archives Currency Converter

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/

Public Statue and Sculpture Association

Louis-François Roubiliac (1702–1762)

https://pssauk.org/public-sculpture-of-britain/biography/roubiliac-louis-francois/

Stained Glass in Wales (University of Wales)

Church of St Giles, Wrexham / Wrecsam

https://catalogue.stainedglass.wales/site/103

Welsh Government

Wrexham Town Centre Conservation Area Character Assessment and Management Plan. 2009

https://www.wrexham.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2023-04/wrexham-town-centre-cons-area-assessment.pdf

Press release: Historic Church of St Giles nears end of essential conservation works. 8th August 2025

https://www.gov.wales/historic-church-st-giles-nears-end-essential-conservation-works

Wrexham’s Year of Wonder 1876 – 2026

https://wrecsam1876.co.uk/

Wrexham.com

Views of 1970s Wrexham From Top of St Giles Tower (most usefully including photos of the Wrexham-Ellesmere railway line that ran just under St Giles until sometime after the railway closed in the early 1980s)

https://wrexham.com/news/view-of-1970s-wrexham-from-top-of-st-giles-tower-100315.html

Wrexham Heritage Trail

Home Page

https://reesjeweller.co.uk/heritage/index.html

Map

https://reesjeweller.co.uk/heritage/mapsmall.html

Town Hill

https://reesjeweller.co.uk/heritage/town_hill.html

xxx