The Celtic cross style headstone of Robert Walter Russell (d.1909) and his wife Louisa Alma (d.1936) is on the left; the grave of Jane Whitley (d.1912), with its elaborate angel, topped with a cross and provided with a kerb and footstone (which is where the dedication is to be found), is on the right, erected by her husband Captain W.T Whitley, late Royal Artillery, who joined her there in 1936.

I have been to dozens of archaeological and historical burial sites, from prehistory onward, including famous monumental 19th century cemeteries in London, Paris and Havana, but the easiest by far to visit for someone based near Chester are local parish churchyards and the later dedicated Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries built during the Victorian period. Ironically, I know much more about the burial traditions of ancient Egypt than I do about those on my own doorstep. Up until now I have been repairing the gaps in my knowledge by visiting parish churchyards, but Overleigh Cemetery represents a different type of experience altogether, part graveyard and part public green space. Overleigh reflects the growth of urban populations in towns and cities “which massed people on a hitherto unimaginable scale” (Julie Rugg, 2008) and put unmanageable pressure on urban parish churchyards. It also demonstrates both a new idealism in the 19th century, the belief in the development of civic resources for the benefit of the general public, as well as the growing awareness of how disease was spread, the dangers of insanitary conditions, and the need for new approaches to public health. The Victorian cemetery introduced into suburban environments the down-scaled aesthetics of 18th century estate parkland, often with their associated Classical architectural features, made popular by landscape designers like Capability Brown. This touches on the complexities of the Victorian cemetery of which Overleigh was a smaller provincial form albeit clearly influenced by more elaborate examples.

Before I go any further, many thanks are due to Christine Kemp for her marvellous help when I started this mini-project. It would have taken me at least twice as long without her, probably a lot longer, and I would have made errors that she has put right, so I am in her debt. Chris has contributed 1000s of grave descriptions from this and other local cemeteries to findagrave.com, and is a founder member of the Friends of Overleigh Cemetery.

Where the findagrave.com website has an entry for a grave owner, I have added the hyperlink to the photographs used on this page for anyone who wants to read the inscriptions or find out more.

There will be five parts to this piece about Overleigh. Part 1 starts with a very brisk and short overview of Chester in the 19th Century and goes on to look at the establishment, in that context, of Overleigh Old Cemetery and Overleigh New Cemetery, followed by a short introduction to the objectives of research activities that can be carried out using cemetery material (discussed more in other parts) and some final comments. At the end it also lists the sources for the entire five-part series, which will be added to as the series is posted.

- Part 1: Introduction to the background and the establishment of Overleigh Cemetery

- Part 2: The living, the dead and the visitor at Overleigh,

- Part 3: Shifting ideas – the move away from monumental cemeteries towards cremations and lawn cemeteries

- Part 4: The research potential of cemeteries; and Overleigh case studies

- Part 5: The Overleigh Old and New Cemetery today and in the future

—-

Chester in the 19th century

Overleigh Old Cemetery opened in 1850, and the New Cemetery opened in 1879. To put this into some sort of context, here’s a very short gallop through Chester in the mid-19th century.

Chester Tramways Company Horsecar no.4 at Saltney. Source: Tramway Systems of the British Isles

Chester had been connected to the greater canal network in 1736, linking Chester with the Mersey, and was connected to the rail network by 1840, with today’s station opening in 1848. The Grosvenor Bridge opened in 1832, taking the pressure off the Old Dee Bridge. A horse-drawn tram was introduced in 1879 to link the railway station to Chester Castle and the racecourse. This was replaced by an electric service in 1903 after Chester built an electricity plant in 1896, which also allowed the 1817 gas lighting to be replaced. Improved communications brought more prosperity, and from the 1830s to the beginning of the 20th century, Chester had become an affluent town with a growing population. To accommodate this rapidly growing population the city suburbs expanded to the south of the river, with Middle Class suburbs developing at Curzon Park and Queen’s Park, with a new suspension bridge built in 1852 (the current one replaced it in 1923) to connect the latter to the town.

Chester Town Hall of 1869. Photograph by Jeff Buck, CC BY-SA 2.0

Signs of prosperity were everywhere. Commerce in the markets, shops and local trades thrived in the mid 19th century, and the sense of confidence and ambition was reflected in the expansion of the 18th century Bluecoat Hospital School, the building of the new Town Hall of 1869, the restoration of old buildings, and the establishment of new buildings, many in the style of earlier medieval half-timbering, as well as churches, including those for Dissenters. With its extensive retail, its race course, its regatta and its medley of fascinating architecture, Chester was becoming a popular destination for visitors, and a series of hotels were built to support the growing tourist industry.

Although the Industrial Revolution did not revolutionize Chester in the same way that it did in other towns and cities, it left its mark, although in a rather piecemeal fashion. As with most towns of the period it had light industry concentrated around the canal basin, as well as over the river in Saltney, and a declining shipbuilding industry. Industries included new steam mills, a lead works, an anchor and chain works, three oil refineries and a chemical works amongst other enterprises. Craft trades included tailoring, shoe-making, milliners, dressmaking, bookbinders, cabinet makers, jewelers and goldsmiths, amongst others. In both town and suburban houses domestic service was an important source of employment for the less well off, as was gardening. In line with the Victorian interest in civic works and promoting education and health, the Grosvenor Park opened in 1867 and the Grosvenor Museum in 1885.

Louise Rayner’s (1832–1924) painting of Eastgate Street and The Cross looking towards Watergate Street. Source: Wikipedia

Although the face of Chester seen by most people was a gracious attractive and prosperous one, there was also a lot of poverty. For those who were not quite on the breadline, but could not afford expensive accommodation a solution was provided by lodging houses of variable quality and pricing, which were growing in number to cater for both temporary visitors and more long-term residents. Far more troubling, there were also slum areas known as “the courts,” which housed the city’s poor. The St John’s parish became particularly notorious but these too were expanding, extending into the Boughton, Newtown and Hoole areas. As agriculture made increasing use of labour-saving techniques, former agricultural labourers and their families moved to urban centres to find work. At the same time, the appalling Irish Famine of 1845-52 drove starving people out of Ireland, and a large influx of impoverished Irish refugees, including entire families, expanded the poorest quarters of Chester and were a source of considerable concern to the authorities. Although charity and church schools took in some of the poorer children, the most impoverished and vulnerable, sometimes the children of criminals and certainly in danger of becoming criminals themselves, were not at first provided for but the problem was acknowledged and three free schools for impoverished children known as “ragged schools” were built, of which more in Part 4.

According to John Herson there was an economic decline after 1870, during which population numbers fell, and Chester became more focused on its retail and service industries and the development of its tourism. I recommend his chapter in Roger Swift’s Victorian Chester for more information about his discussion of the three phases of Chester’s Victorian past (see Sources at the end).

A solution to overflowing churchyards

Population in Chester and suburbs by year in 19th Century Chester. Source of data: John Herson 1996, Table 1.1, p.14

Polymath and diarist John Evelyn and architect Christopher Wren had both proposed out-of-town cemeteries in the 17th century, but their suggestions had fallen on deaf ears. An exception was the famous Dissenter cemetery at Bunhill Fields, established from a sense of spiritual necessity.

The rising population that lead the living to move to new areas around Chester, was also a problem for churchyards. The condition of Chester’s city churchyards was very poor, in common with other cities and towns throughout the country, and as the population expanded the situation in churchyards became somewhat desperate, and the new cemeteries were a necessity. John Herson’s chapter in Roger Swift’s Victorian England provides a table of population figures for Chester and its suburbs from 1821 to 1911, and this shows that the population was rising rapidly. Rising populations and the concentration of people in towns had lead to parish church cemeteries becoming problematic all over Britain. This was infinitely worse in big-city urban environments where manufacturing industries had become major employers, where the lack of churchyard capacity led to some truly dreadful, squalid scenes representing appalling health risks, but even in a county town like Chester the problem was very real and churchyards there too were struggling to meet demand.

George Alfred Walker’s “Gatherings from Graveyards“

Complaints were growing about the unsanitary condition of full intramural graveyards, and the risks that this represented. Typhoid, typhus, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, measles, influenza and cholera, were all infectious diseases that were common in Victorian England, and the establishment of new graveyards for minimizing risk was becoming increasingly important as the links between health and sanitation were established. Jacqueline Perry says that between 1841 and 1847 the annual average was 700 burials in Chester alone.

Those arguing for a new cemetery in Chester as a response to this problem were able to point to other specialized graveyards in Britain and overseas. Bigger city cemeteries had been established earlier in the 19th century in Paris (in 1804 Père La Chaise was the first municipal cemetery in western Europe), Liverpool (Liverpool Low Hill opened in 1825 and St James’s Cemetery opened in 1829). In 1830 George Carden, after years of campaigning, organized a meeting to discuss how to improve the burial situation in London and Kensal Green opened in 1833, which initiated “The Magnificent Seven” ring of London cemeteries. Glasgow’s remarkable Necropolis followed in 1833.

In 1839 surgeon George Alfred Walker published his Gatherings from Graveyards (including the subtitle And a detail of dangerous and fatal results produced by the unwise and revolting custom of inhuming the dead in midst of the living), which drew uncompromising attention to some of the horrors of churchyards, encouraging burial reform and the wider adoption of the out-of-town cemetery. I have provided a link to an online copy of this book in the Sources, but it is absolutely not for the faint-hearted. Although this trend was challenged by the Church of England, which derived an income from burial fees, the need was acute, and parish churches were compensated for their loss of income. Most of these new cemeteries were commercial, charging for burials and paying dividends to investors from their profits.

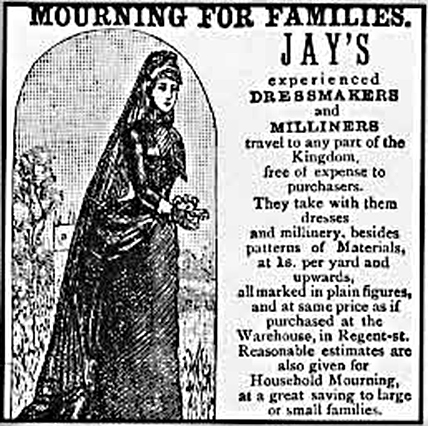

Mourning clothes were a major investment in the Victorian funeral ceremonies. Source: Wikipedia

There was also clearly a psychological need for new cemeteries with neatly defined and delineated plots for individuals and families, and the space to commemorate and mourn loved ones. As James Stevens Curl explains: “It could never be said that the Victorians buried their dead without ceremony. Apart from the immediate family, all the distant relatives would be present . . . Friends, business associated, acquaintances would all appear . . . A dozen or sometimes more coaches therefore followed the hearse.” The acts of observance and the rituals associated with death in the Victorian period, and the traditions associated with the bereavement that followed interment were elaborate, encoded and important to Victorian religious beliefs and social conventions. These beliefs and conventions were part of a deeply felt attitude to death and how it should be handled. They were also opportunities to display wealth and status for those who had it. The new landscape-style cemeteries offered the opportunity to carry out these various rituals at each stage of bereavement after loss with dignity and ceremony.

Following the new cemeteries and the success of the concept, cemetery design became a recognized field of endeavor for landscape designers and architects, and the best known cemetery designer, although by no means the first or even the best, was probably John Claudius Loudon, who consulted on a number of projects before publishing his 1843 On the Laying Out, Planting and Managing of Cemeteries, which became an important source of practical advice and creative ideas for many private enterprises. Loudon’s intentions are captured in these two statements from the beginning of his book:

Cemetery design for a hilly location by Thomas Loudon, 1834, showing a similarly sinuous arrangement as Overleigh, but with the building centred at the heart of the cemetery. Source: Loudon 1843

The main object of a burial-ground is, the disposal of the remains of the dead in such a manner as that their decomposition, and return to the earth from which they sprung, shall not prove injurious to the living; either by affecting their health, or shocking their feelings, opinions, or prejudices.

A secondary object is, or ought to be, the improvement of the moral sentiments and general taste of all classes, and more especially of the great masses of society.

The means by which Loudon proposed to address his “secondary object” was by introducing a sense of serenity, providing fresh air and a sense of nature, and encouraging contemplation. At the time disease was thought to be conveyed by “miasmas” or vapours, not entirely unsurprising given how bad cesspits, uncovered drains and overfilled graveyards smelled, and trees were thought to assist with the absorption of miasmas, helping to promote good health and prevent the spread of disease. Often his designs were based on a grid, like the 1879 Overleigh New Cemetery, but his above design for cemeteries on hills and slopes, like the Overleigh Old Cemetery was more forgiving.

Sculptural monument on a plinth dedicated to land agent and surveyor Henry Shaw Whalley, d.1904

After the 1850s commercial cemeteries were not the standard way of establishing new cemeteries. The Metropolitan Interments Act allowed for burial grounds to be purchased by a civic authorities, which was itself replaced by a new Act of Parliament in 1852 when Burial Boards were established, after which publicly funded cemeteries became the norm.

One of the results of the new cemeteries, with individual plots dedicated to single individuals or to families, was that graves became part of the domestic sphere of families, part of their personal real estate. In an elaborate cemetery this might include personal family mausolea and vaults, but at a more modest provincial cemetery like Overleigh, it usually consisted of a sculptural element or a headstone with a kerb and sometimes a footstone, although at Overleigh footstones are unusual (all the elements are in the grave shown at the top of the page, on the right). This created a clearly defined space in which family and friends could commemorate their dead with gifts of flowers and sometimes additional memorabilia. The main sculpture or headstone, usually of stone but occasionally of metal, was itself a medium for expression, combining shapes, symbolic and sentimental imagery, and text to express ideas about both the dead and their relationship to the living. The kerbs were usually visited and the dead were gifted fresh flowers or immortelles (more permanent artificial flowers presented in suitable vessels or frames, sometimes under a glass dome).

Overleigh Old Cemetery

Overleigh Old Cemetery, very convenient for Chester residents without intruding on the town itself, lies just across the Grosvenor Bridge, its northern border running along the south bank of the river Dee. It has gateways from the Grosvenor Bridge, Overleigh Road and River Lane which converge on the monument of, cenotaph to William Makepeace Thackeray, a Chester doctor and benefactor. Although this is the oldest of the two halves of the cemetery, it is still in use today for new cremation memorials in its maze-like hedged memorial area (actually designed to look like ripples on the lake that once occupied the space), as well as an enclosed area for interments and cremated ashes of babies, which is inevitably particularly sorrowful. Overleigh Old Cemetery is often used as a short-cut from the Grosvenor Bridge to the walkway along the Dee, and presumably as its designer Thomas Penson originally intended, always has the feeling of a public park as much as a cemetery, although up until late August 2024, there has been nowhere to sit. A bench supplied by the Friends of Overleigh Cemetery has helped to bring the cemetery further into the public domain.

The cemetery was established by The Chester Cemetery Act in 1848. Chester’s City Surveyor, Mr Whally had held a public inquiry at the Town Hall to discuss the urgent need of a new extramural cemetery. Overleigh was established by a private company named the Chester General Cemetery Company, which was formed by an Act of Parliament on 22nd July 1848. According to Historic England, the cemetery site was owned by the Marquis of Westminster who exchanged it for a shareholding in the company. The cost of the cemetery was estimated at £5000 but the company blew its budget and in 1849 work was forced to stop for seven months until new shareholders could be found. The thinking behind it was, much like the Grosvenor Park and the museum, as much a matter of civic pride as it was a practicality. However, unlike the park or the museum, the cemetery was intended to turn a profit, and was essentially a retail operation, selling or renting burial plots, paying for its own maintenance and offering a return on shareholder investment, and providing a valuable service to residents at the same time.

Crypt Chambers, Eastgate Street. Source: Wikipedia

Overleigh Old Cemetery was designed by Thomas Mainwaring Penson (1818–1864), the surveyor and architect responsible for, amongst other Chester buildings, the 1858 Crypt Chambers and the 1868 Grosvenor Hotel, both on Eastgate Street. The original layout of Overleigh Old Cemetery is preserved in an engraving from sometime after it opened, shown below, probably in the later 1850s.

Following the model already established in Paris, Belfast, Glasgow, Liverpool and London, this was a garden- or landscape-type cemetery, planned to emulate a large garden or small park. When compared with some of the vast architectural entrances to the great Victorian cemeteries of Liverpool, Glasgow, London and elsewhere (see, for example, Kensal Green or, in a different style, the Glasgow Necropolis) the gates at Overleigh are a mere nod to a transitional zone between the busy outside world and the quiet necropolis within, with modest pillars and iron gates, shown above. The buildings that were once just inside each gate, the entrance lodges, will have given more of sense of entry and exit than the entrances retain today. Something of that effect can be seen over the road at Overleigh New Cemetery where the lodge building survives. The funeral cortege would stop here to be formally received and recorded before proceeding to the burial site.

Overleigh Cemetery. Source: Wikipedia

The cemetery was landscaped with sinuous wide driveways winding down the hill towards a lake, laid out over an area of some 12 acres. In the engraving to the right there are six buildings, none of which survive today. I have no information about why they were taken down, but assume that they had fallen out of use and were becoming a problem to maintain. Two of them are lodges at the Grosvenor Bridge and River Lane gates of the cemetery, used by cemetery superintendents and officials, and housing cemetery records. One of the lodges was apparently removed in 1967. Chris has a plan of the cemetery dating to 1875 that identifies the church-like buildings at the top and the one by the lake as mortuary chapels (the one by the lake was for Dissenters), whilst the building behind the temple-style monument to Robert Turner was the Chaplain’s house. It may have had rather good views over the bridge and the river. The tiny building at centre left was probably a grounds-man’s hut, used for storing tools.

The headstone of Harriett Garner (d.1905) and other family members. Harriett was a suicide, but because the inquest found her to be temporarily insane, and therefore innocent of crime, she was allowed to be buried in a consecrated grave

The 1847 Cemeteries Clause Act (section 36) stated that a new cemetery contain both consecrated and unconsecrated land and there were usually two chapels, one Anglican and one for Dissenters. The provision for non-Anglican graves had become particularly important because of the Nonconformist movement, which had grown from strength to strength. Non-denominational chapels of rest, where the deceased could be laid before interment, were a characteristic feature of the new cemeteries. The idea of including unconsecrated land was to ensure that a cemetery should exclude no-one, including suicides who were declared sane at the time of their deaths (those judged to be insane when they committed suicide were considered to be innocent), unbaptized children and those of non-Anglican religions. Chris showed me where, indicated by marker stones, there is a section for Roman Catholics and another for Dissenters, whilst pauper graves, some of which surprisingly have headstones, are dotted throughout the cemetery. For those short of funds, there were burial club schemes, a little like life assurance today, where people could pay in a regular amount to save up for a proper ceremony and gravestone.

Plantings to give the garden cemetery its Arcadian feel included both deciduous and evergreen trees. The use of deciduous trees was counter to Loudon’s advice, as in his view they grew too fast, became too big, dropped leaves that had to be cleared up, and looked ugly with bare branches in the winter, but at Overleigh the combination provides a marvelous mixture of colours, textures and shapes for most of the year. The trees are worth a study in their own right, including some very unusual specimen varieties. The now truly massive and splendid redwoods and traditional yew trees, both of them evergreen and long-lasting, often represent the hope for eternal life, and the sheer variety of specimen deciduous trees is remarkable and if anyone out there happens to be a tree expert and would like to help me out with some identifications, I would be grateful!

The William Thackeray cenotaph that sits at the conjunction of the cemetery drives. A huge beech tree stands behind it, and in front of it is a big horse chestnut; the trees in Overleigh are one of its most appealing features

The lake was eventually filled in, a very nice feature but presumably something of a problem to maintain and probably a risk to children and of course was using up land that could be used for more graves. Partially in its place is a cremation area made of concentric hedging to emulate the ripples on the former lake. The cremation memorial will be discussed in part 3. The rustic bridge to the right of the lake on the engraving remains in situ, although the land either side of it is being used as a dumping ground for clearance works, which will eventually biodegrade and build up the soil level around the arch bases, which is a real shame.

The William Thackeray monument, at the confluence of the Old Cemetery drives has already been mentioned, but in the engraving above, the tall, slender temple-style monument shown at top right of the image, which commemorated brewer and wine merchant Robert Turner, who was Sheriff of Chester in 1848. The plinth now sits directly over the base, with the fallen pillars at its side. The engravings are on the floor of the base, which would once have been visible by walking into the monument and looking down, one for Robert Turner and one for his wife, which are shown on the findagrave.com website (by Chris Kemp). There’s a certain amount of irony in its demise, as over the course of the Victorian period the brewery industry also went into a state of terminal decline. Work was done by Blackwells Stonecraft to prevent it sliding down the slope in 2022.

Robert Turner’s grave (d.1852) as it now appears in the oldest part of Overleigh Old Cemetery. Christine Kemp has posted a fascinating photograph of it under repair in 2022 on the findagrave website at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/195750339/robert_hugh-turner/photo#view-photo=247132692

Overleigh New Cemetery

Overleigh New Cemetery, with the Greek Orthodox church, formerly a cemetery chapel, in the background

Overleigh New Cemetery, established in 1879, lies to the south of the Old Cemetery, with the Duke’s Drive running along its southern boundary, accessible via its entrance on Overleigh Road, opposite the entrance to the Old Cemetery, which gives some sense of continuity, and this too is still in use. Overleigh New Cemetery, established in 1879, is a more obviously lower budget incarnation, all on the flat, its driveways laid out on a grid that divides the cemetery into raised rectangles. Loudon’s book had layouts very like this in his 1843 book, although they weren’t amongst his more imaginative designs. They did, however, have the essential idea that Loudon proposed of trees and shrubs to create a healthy and contemplative experience, and these are largely missing from Overleigh New Cemetery, except around the very edges. By virtue of the fact that it does not serve as a route to anywhere else, and is essentially a cul-de-sac, it is more peaceful than the Old Cemetery but has less of a feeling of community.

*****

There is a small and beautifully maintained section dedicated to Commonwealth War Grave Commission graves, and managed by the Commonwealth War Grave Commission itself, is an important reminder of the sacrifices that were made, although graves dedicated to those who lost their lives in combat are also dotted through both the Old and New cemeteries. These are planted with evergreen and flowering shrubs, and carry just the right balance of dignity, solemnity and floral tribute. It was decided, when they were originally designed that there should be no distinction between graves of different rank so the headstones are all made according to a standardized template, differentiated by the regimental crest and or badge, the ranks and of course the names of the deceased.

One of the chapels in Overleigh New Cemetery, a Designated Heritage Asset in the Cheshire West and Cheshire “Chester Characterisation Study”

There are four buildings in the New Overleigh Cemetery. The largest is the West Chapel, now Saint Barbara’s Orthodox Church. Historic England states that it was built in the style of John Douglas in the early 20th Century. Chester Council made it available to the Greek Orthodox church in the 1980s and it opened its doors to congregations in 1987. It attracts a congregation from a very wide area and prevents the site feeling entirely field-like. Also assisting in this sense of place rather than space is a lodge that sits near the Overleigh Road entrance but is now apparently used as a private residence. The small chapel, now used as a base for cemetery workers, is a lovely little thing with a few nice decorative features inside and out and some understated stained glass consisting of small square panels in quiet colours. It was nicely thought through when it was built, and is now a Designated Heritage Asset.

The other building, recently fenced off presumably due to the sorry state of repair, making it look like a complete eyesore, is the former grave-digger’s hut, a charming brick-built building, described as “an important historical feature” in the Handbridge Neighbourhood Plan. It is clearly in urgent need of help.

—–

Headstone of Frederick Coplestone, d.1932 and members of his family by sculptor Eric Gill, showing St Francis of Assisi (Grade 2* listed)

When you first enter the New Cemetery, the initial impression given by the repeated lines of headstones is that the cemetery is less obviously interesting than the variety of shapes and sizes over the road. This is, however, partly an illusion caused by the grid-like horizontal layout. Closer inspection of the older sections, nearest to Overleigh Road, demonstrates that these too offer an enormous amount of variety that provides insights into personal preferences and choices, and certain very specific affiliations. The graves here, many of them more recent than those at the Old Cemetery, offer a rather different sense of style and character, of different experiments with more personalized design and symbol as new trends emerged. There are, for example, some interesting Art Nouveau and Art Deco examples that I have not noticed in the Old Cemetery.—-

As you head to the extremities furthest from the road, you will see less of these mainly earlier 20th century monuments and find yourself confronted with the more modern emblems of British commemoration of the dead. These are generally smaller and plainer, often with flowers or other memorabilia, and reflect a changing attitude to memorializing the dead. The further on you go, the more you find yourself in the sort of “lawn cemetery” concept that is becoming increasingly popular for public cemeteries, with small memorials. Although this is much less aesthetically engaging than the older cemeteries, it does reflect an interesting change in mortuary practices that will be discussed further in parts 4 and 5.

**

Family Research

It does not take a great deal of imagination to see that a cemetery like Overleigh contains an enormous amount of information about people who have lived and died in and near Chester. Most of this information comes from words on gravestones, although some general comments can be made about the imagery employed and the design of the grave monuments themselves. There is as much fashion as there is tradition, all mingled together. Classical elements, Gothic Revival, Art Deco, Art Nouveau are all here, and in Overleigh New Cemetery the differences between Anglican and Roman Catholic graves are often particularly striking. One way of learning more about the cemetery as a whole is by taking the Stories in Stone walking tour with one of Chester’s excellent Green Badge Guides, which takes visitors on a tour of the main features and some particularly interesting graves.

Grave of William Pinches (d.1929), Overleigh New Cemetery

The most common motivation for conducting research at cemeteries is to find the grave of an ancestor or loved one, whilst others find real interest in the individual stories told by gravestones via design, symbol and inscription. Although Overleigh is so large that it may all seem like a challenge to make sense of it all, if you know the name of the grave’s owner, the findagrave.com website is an excellent database containing details of the grave and its owner, where known, together with any interesting stories that might be connected with either the grave or the owner. Chris Kemp alone has been responsible for researching and adding literally thousands of graves in Overleigh and elsewhere in the Chester area since she began to record them over 12 years ago. There are other online databases that do something similar, but findagrave.com is probably the most accessible resource for Overleigh. Note that findagrave.com divides the cemetery into the Old Cemetery and the New Cemetery for search purposes. Chris points out that until 1879 when the Overleigh New Cemetery was built, the Overleigh Old Cemetery was at that time known and referred to in documents as the “new cemetery.”

The Cheshire Archives and Local Studies service has some excellent online resources, and as well as their Overleigh Cemetery 1850-1950 database (it’s not the most user-friendly interface, so do watch the video about how to use it here), there are many other sources of local information about individuals, institutions and business in their online Archive Collections, including parish records, the electoral register, business directories, court sessions and poor law and workhouse records.

Amongst many other activities, Chris Kemp receives emails from people looking for graves from outside the area, and sometimes overseas, and tracks down the graves for them, a valuable and time-consuming task, as she receives at least half a dozen every week, which she hunts down every Saturday, and which demonstrate how much the cemetery, on both sides of the road, continues to contribute to people’s investigations of their past and their sense of a link with their family history.

———–

Part 1 Final Comments

Many of the first out-of-town cemeteries were conceived of as memorial parklands that were designed to balance the natural and the man-made, to harmonize different needs and priorities. Although at Overleigh each of the two halves of the cemetery has a different personality, both combine monument and commemoration within a designed space where the dead and the living can peacefully coexist. The graves themselves, some of them impressive, others very modest, never reach the heady heights of London’s “Magnificent Seven” with their extravagant mausolea and world-famous names, but in the details, the variations and subtleties, and of course in the engravings, there is a very real sense for visitors of mingling with the lives of Chester residents and getting to know something about the population at large.

Many of the first out-of-town cemeteries were conceived of as memorial parklands that were designed to balance the natural and the man-made, to harmonize different needs and priorities. Although at Overleigh each of the two halves of the cemetery has a different personality, both combine monument and commemoration within a designed space where the dead and the living can peacefully coexist. The graves themselves, some of them impressive, others very modest, never reach the heady heights of London’s “Magnificent Seven” with their extravagant mausolea and world-famous names, but in the details, the variations and subtleties, and of course in the engravings, there is a very real sense for visitors of mingling with the lives of Chester residents and getting to know something about the population at large.

Detail from the headstone of Margaret Roberts (d.1900), Overleigh Old Cemetery

The gravestone is, just as much as items given pride of place in the home and passed between generations, both an object and a commodity. It was manufactured, chosen, customized, purchased and curated. Even within its own funerary landscape, the funerary monument had a role within the home, in that it formed part of a personal experience of the world, a form of mental mapping that includes places beyond the front door but are endowed with a personal value. They become part of a much wider family and social landscape than their physical location in a cemetery. This means that there is a social and cultural history component to be researched in large cemeteries that offers a different type of record from documentary resources. I will talk more about the role of cemetery research in social and cultural history in Part 4.

Overleigh is a place where relatives can visit their loved ones or carry out genealogical research into their ancestors and where social history can be investigated. At the same time it needs to be respected and to be recognized as a vulnerable piece of local heritage. One of the most important questions about any monument or object is what happens when it is no longer valuable to someone, when the useful life for which it was intended comes to an end. At this point, so many bad decisions have been made in Britain about the value of buildings and objects to social and cultural history, and there is a need to ensure that cemeteries like Overleigh continue to both support and inform the living. This will be discussed further in part 5.

Part 2, only part-written at the moment, will look at how the living and the deceased are both incorporated into a common language of the necropolis, and how gravestones are used to express complex ideas about the dead.

***

With sincere thanks again to Christine Kemp for giving me a guided tour of both parts of Overleigh Cemetery at the beginning of August 2024, and then guiding me to find specific graves and helping me to understand different aspects of the cemeteries when I met her again at the end of August, and for offering ongoing help. In this and the following parts, she has been a splendid source of information, fact-checking and guidance. Any errors are, of course, all my own work!

Sources:

The books and papers and websites used in all the parts are listed in their own page. Splitting them up over the various parts does not make much sense because so many of them are used time and time again and listing the sources in one place makes it easier for anyone wanting to print off the full list.

The list of references for this post has become ridiculously long, so instead of listing them here on the page I have copied them onto their own page on the blog at

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/walking/overleigh/