Cadw sign at the site showing a cutaway of how the interior of the Valle Crucis abbey church may have appeared

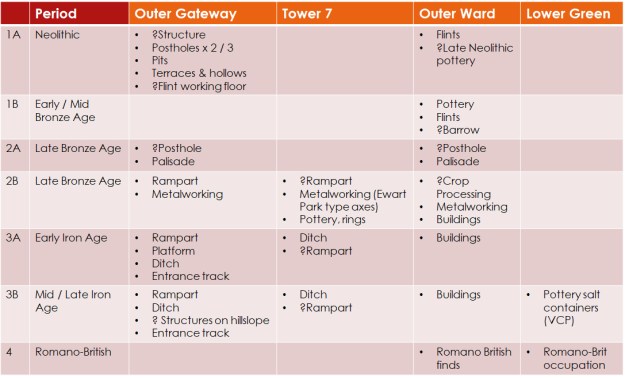

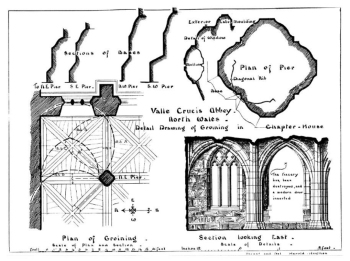

Part 1 of this series about Valle Crucis Abbey near Llangollen introduced the background to 12th Century monasticism in Britain, via St Pachomius and St Benedict, and talked about the Cistercians, the spread of the Cistercian order in Wales and why Valle Crucis was located where it was. Part 2 looked at how the buildings at Valle Crucis were used and how the monastic community functioned. Part 3 looked the architectural development of the abbey, an architectural jigsaw of a story from foundation in 1201 to dissolution in 1536.

Part 4 and upcoming part 5 look at how the patrons, abbots, priors and monks of the Cistercian Order contributed to life at Valle Crucis. In Part 4, the top levels of the abbatial hierarchy are introduced, and in Part 5 the main body of the monastic community is described, all helping to build a view of what sort of people were to be found at the abbey, and what life was like within the cloister.

It is the way of the literate world that more is known about those at the top of the hierarchy than those of the main body of the community, because it is the patrons and abbots whose names were on formal documentation, and who were accountable to the mother abbey at Strata Marcella, to the General Chapter at Cîteaux, to the pope, and ultimately to God. More mundanely, the abbots were also subject to the vagaries of political activity and war, and as leaders of the abbey were named as its representatives. Even so, there are considerable gaps in the list of abbots at Valle Crucis, many of whom are simply unrecorded and others are known only by their names, and even then not always with certainty, and sometimes only partially.

dsfsdfsdfs

Normans, Cistercians and Welsh princes

The remains of Strata Florida in midwest Wales. Photograph by Jeremy Bolwell. Source: Wikimedia

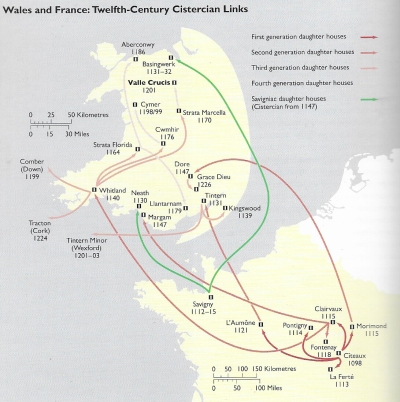

Although Wales had its own monastic tradition both before and after the Norman invasion in 1066, by 1150 Norman lords had established houses attached to a number of monastic orders in Wales, connected with French orders. The Normans also set about normalizing the priesthood, bringing it under the archdiocese of Canterbury, and a number of new dioceses were established, each under a new, Norman-sponsored bishop. Welsh Cistercian monasteries were spawned by the Anglo-Norman abbeys in Tintern and Whitland in the south. Whilst Tintern remained embedded in the Norman-Marcher tradition, Whitland’s fortunes became bound up with the Welsh princes in the 12th century when the Lord Rhys ap Gruffudd restored the fortunes of Deheubarth by claiming it from the Anglo-Norman Robert fitz Stephen. Lord Rhys assumed patronage of both Whitland (founded with monks from Clairvaux) and Strata Florida in mid-west Wales (founded with monks from Whitland), the latter initially founded by fitz Stephen. The new Welsh monasteries spawned by Whitland spreading from south to north, were all founded with this sense of being true to the Cistercian order, the spirts of St Benedict, the Virgin Mary and Christ, but were, at the same time, Pura Wallia, pure Welsh.

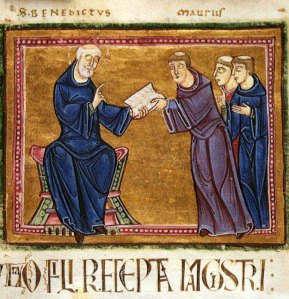

The regulations and charters of the Cistercians formalized the original intentions of St. Robert of Molesme Benedictine Abbey, who founded the Cistercian order in 1098. Robert was was conscious that the labora component of the Benedictine motto “ora et labora” (prayer and work) had been largely abandoned. In the Cluniac order in particular there was too much comfort, a lot of elaborate and time-consuming ora and very little labora. Cistercian abbeys were intended to be self-sufficient, combining work, prayer and solitude, distant from the distractions of urban areas. This was Robert’s vision for the New Abbey at Cîteaux. Robert was recalled somewhat forcibly to Molesme to resume his role, but was succeeded as abbot at the New Monastery by Alberic (1099-1109), who built on Robert’s initial work and successfully obtained papal privilege for the new abbey and its community in 1100. Alberic was in turn succeeded by Stephen Harding in 1109, an English monk and theologian who consolidated his predecessors’ work over the next 25 years.

The New Monastery at Citeaux as it is today. Source: European Charter of the Cistercian Abbeys and Sites

Abbot Stephen Harding is usually credited with much of the underlying structure that ensured the success of the Cistercian order. He appears to have understood that new abbeys, each one its own world isolated from its predecessors and peers, meant that standards would be difficult to maintain. One of his priorities was to standardize life throughout the Cistercian network of abbeys, to ensure conformity to both the Benedictine Rule and Cistercian values, and it is generally thought that he produced the official constitution for the Order, the Carta Caritatis (Charter of Care), ratified by the Pope in 1119. Amongst other regulations were a number that dealt with governance and accountability. The governance was to ensure that all abbeys had the resources to conform to the Cistercian vision. The accountability was the means by which abbeys were monitored, disciplined and assisted.

Aerial view of Valle Crucis. Source: Coflein

Records of life at Valle Crucis are sketchy. To complicate matters, as the centuries passed and the Cistercian order relaxed some of the more severe of its dictums, daily life changed accordingly. This means that there is no single Valle Crucis way of life because as ideological decay set in, so did the way in which lives were lived. This phenomenon of gradual departure from early Cistercian values is by no means unique to Valle Crucis, and was remarkably consistent across the Cistercian abbeys and across the centuries. Some of this is visible at Valle Crucis, and the records that do survive give some insights into a few of the peaks and troughs at Valle Crucis. Between what is known about Valle Crucis and what is known about Cistercian abbeys in general, we can make a fair stab at getting to know some of the people and their roles.

asfdasdf

Patronage of the abbey

The founder and first patron of Valle Crucis

Cistercians might seek relatively remote locations, but they never made any decisions about founding new abbeys without the input of the Cistercian order, local senior clergy and influential secular local dignitaries. The most important of these secular authorities was the patron who put up the money for the building of the core monastic buildings, including the church, and provided the abbey with lands to secure its income. Welsh monasteries were not merely religious but had a political and territorial role.

Prince Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor of Powys Madog (north Powys, northeast Wales) was the last of the major landholders in Wales to invest in a Cistercian establishment, and was convinced by four of the nearest abbots that he should found a monastery in his territory, extending the reach of the Cistercians in Wales. Investing in Valle Crucis was not a light-hearted undertaking. As well as land on which to establish the monastic precinct (the monastery buildings, the abbey church, the gatehouse, storage facilities and possibly farm buildings), the abbey had to be allocated lands to ensure that it could at least achieve self-sufficiency and, ideally, to make a profit to fund future activities. Although monks took a vow of poverty, some abbeys and priories became very wealthy in their own right. In the case of Valle Crucis, endowment first meant relocating the village that already occupied the land chosen for the abbey, and providing it with land and other properties, such as mills and fishing rights. The lands subsequently allocated to the abbey, both highland and lowland, suitable for livestock grazing and agricultural development respectively, had previously fed into Madog’s own coffers.

Depiction of purgatory in the 15th Century Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. Source: Wikimedia

In return, what did Madog acquire to compensate himself for the ill-will of villagers and farmers, the loss of a useful revenue stream? The position, prestige and identify of the Welsh princes in the 12th Century was dependent not merely upon political power, but also on spiritual security, which could be secured by investment in monastic establishments and the prayers that would be dedicated to them by the monks. Richard Southern’s epic narrative about the Middle Ages emphasises the importance of monasteries to patrons (p.225):

The battle for the safety of the land was closely associated with the battle for the safety of the souls of their benefactors. It was this double objective that induced great men to alienate large portions of their property for monastic uses. They and their followers and families . . . believed that their temporal and eternal welfare equally depended on the warfare of the monks.

At the same time, his personal prestige would grow along with the monastery. He had achieved a new status, a validation of his authority and a connection into the wider European world of erudition, culture and divine integrity represented by the spread of the Cistercians and their influence. With a Cistercian abbey in his heartland, no-one could accuse any ruler of presiding over an uncivilized land. The spread of the Cistercians in Wales was often connected with reinforcing power, prestige and identity, whilst still maintaining a Welsh personality all wrapped up in a nicely Christian package. A neat trick.

By investing in a monastic establishment, Madog also stayed on the good side of the Church. More importantly, what he obtained for himself and his family was the most important direct commodity that the abbey had to offer – its prayers. As the horrors of purgatory loomed ever closer, patrons hoped that the strength and integrity of monastic prayer would offer powerful intercession. The prayers of monks who were so close to the divine might work wonders on behalf of the deceased and his family. Although the Cistercians initially banned burial of secular people within monastic premises, no matter how important, this rule was not observed at many Cistercian monasteries, and certainly at Valle Crucis part of the arrangement seems to have included the burial of Madog and members of his family within the monastic precinct, yet another step nearer to God.

Patrons descended from Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor

When Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor, prince of Powys Fadog (north Powys) died in 1236, his son Gruffudd Maelor ap Madog (c.1220-1269/70), appears to have taken over most of the responsibilities of Madog’s role, although the domains were split between all five of Madog’s sons. It was Gruffudd who in the year of his father’s death re-confirmed the founding charter, meaning that Valle Crucis retained the properties and assets that had been bestowed upon it by Madog. He had two sons, Gruffydd Ial ap Madog and Madog ap Gruffydd Maelor. The family had complicated allegiances, swapping sides between the Welsh and the English, but retained their lands until Edward I took Powys Fadog in 1277. Gruffudd’s sons were both buried at Valle Crucis, and had presumably taken over the patronage as their father had done before them.

Patronage under English rule

Valle Crucis, located in a part of Powys known as Bromfield and Iâl, found itself in the middle of several political tugs of war and it is difficult to know what sort of patronage followed between the death of Gruffyd and the suppression of Valle Crucis in 1536. The answer lies somewhere in the history of Bromfield and Iâl, which had become something of a diplomatic bargaining chip. It seems worth recounting some of that history in order to highlight how political complexities could impact both Valle Crucis and other monastic establishments in Wales.

Following Edward I’s conquest of Wales Edward I’s reparations to Valle Crucis were generous, but these were intended for replacement of stock, repairs to property, and general compensation for the injury to the dignity of the monastery, but Edward did not replace the Powys princes as patron. Madog ap Gruffyd, the great-grandson of founder Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor, was buried in the abbey in 1306, as was his cousin Gweirca, implying that they continued to support the abbey even after Edward I. However, on the death of Madog ap Gruffyd everything changed.

Much of the following has been based on information from the 1992 doctoral thesis The Welsh Marcher Lordship of Bromfield and Yale 1282-1485 by Michael Rogers (any errors are, of course, my own). Rogers quotes a charter of Edward I from 7th October 1282 at Rhuddlan:

Notification that the king, for the greater tranquillity and common benefit of him and his heirs and of all his realm of England, has granted by this charter to John de Warenne, earl of Surrey, the castle of Dinas Bran, which was in the king’s hands at the commencement of the present war in Wales, and all the lands of Bromfield, which Gruffudd and Llywelyn, sons of Madog Fychan, held at the beginning of the said war . . . saving to the king the castle and land of Hope . . . ; and the king also grants to the earl the land of Yale, which belonged to Gruffudd Fychan, son of Gruffudd de Bromfield, the king’s enemy; doing therefor the service of four knights’ fees for all service custom and demand . . .

Seal of John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey. Source: Wikipedia

Two years later in 1284, John de Warenne granted Bromfield and Iâl to his son William, who died young in 1286. The crown once again took possession whilst John tried to claim his rights to the lands, but in the following year Bromfield and Iâl were restored to John, in spite of possible claims of William’s baby son, also John, born in 1286. When John de Warenne died on 27th September 1304, his grandson and heir, William’s son John was still a minor and became a ward of the king, with Bromfield and Iâl remaining in crown hands until 1306.

The history of Bromfield and Iâl was tied closely to the history of the village of Holt, which was also given to John Warren on Madog’s death, and which also passed to William. John began the castle, which William subsequently continued to build. Holt and its castle passed by marriage into the hands of the Earl of Arundel, who fell foul of Richard II and was executed. After reverting to the crown and again being granted to the Earls of Arundel, Holt and its castle were granted by Richard III to Sir William Stanley, together with Chirk Castle the lordship of Bromfield and Iâl (now known as Yale) in 1484. It is this family that appear to have taken on the patronage of Valle Crucis. Unfortunately Stanley was himself executed for treason in 1495. Holt Castle next passed to William Brereton, who was apparently also a patron of Valle Crucis, before being executed in 1536 under Henry VIII for most foolishly tinkering with Ann Boleyn. Bromfield and Iâl was then transferred to the crown under Henry VII and subsequently Henry VIII.

Sir William Stanley. Source: Wikipedia

In 1536 the Act of Union withdrew the special status of the Marcher lordships, and Bromfield and Iâl were incorporated into the new county of Denbighshire, together with Chirkland, Denbigh and Dyffryn Clwyd. 1536 was a momentous year for Bromfield and Iâl, and marked the dissolution of Valle Crucis.

After the death of Madog, with Bromfield and Iâl passing to John de Warenne, Valle Crucis had now of passed from the Welsh line to the English. In spite of its location in the territory of Bromfield and Iâl, it is by no means clear whether Valle Crucis received any real material support from de Warenne or subsequent owners of the land. On the other hand, it seems as though the descendants of the former Welsh ruler of Powys Madog still took an active interest in the abbey, and that local landowning patrons may have been involved with the abbey’s writing of Welsh history and its connection with Welsh poets, whom local gentry also supported. The Trefor family, from whom two of the 15th century abbots as well as bishops of St Asaph were derived, is one example.

It was not until the arrival of Sir William Stanley in the picture that clear support for the abbey is once again demonstrated. Whilst it is possible that the Stanley family may have continued to support the abbey on a private basis after Sir William’s death, it is more likely that reversion to the ownership of the crown changed the abbey’s circumstances yet again. Eventually Bromfield and Iâl passed to Henry Fitzroy, duke of Richmond and Somerset, who became the patron of Valle Crucis and who was involved in untangling the problems that ensued, not long before the dissolution, under Abbot Robert Salusbury.

I suspect that there is a lot more to be said on the above, and hope to dig out some more details as I continue to look into Valle Crucis.

Abbots of Valle Crucis

One of the ways in which Cistercian standards were maintained was in the strict hierarchy of the abbey. The senior position was abbot, who was supported by a prior and, at larger establishments a sub-prior. Beneath them were the choir monks who made up the primary community of the monastery. Although monks were in theory equal in status, many of them had particular responsibilities, and the requirement for self-sufficiency meant that these roles were very clearly delineated and were of importance to the smooth running of the abbey. The monks assigned certain roles were called obedientiaries. The monks will be discussed in part 5.

The role of the abbot

The most important person in the abbey was the abbot (from the Greek abbas, father). He would normally be assisted by a prior, the second in command. The abbot was responsible for maintaining order according to the Cistercian regulations. He was accountable to both the mother abbey, Strata Marcella in mid Wales, as well as the founding abbey, Cîteaux, for the abbey’s performance and adherence to Cistercian standards, as well as for internal morale and discipline. An abbot could have been a prior or an experienced monk before being elevated to the most senior position within a new abbey. He could be promoted internally from within his own abbey or another Cistercian abbey on the retirement, death or elevation of a predecessor. Alternatively, when a new abbey was established the mother house provided the abbot and monks, and the new abbot was responsible for managing not only the monks but also for overseeing the building of the monastery and its church, a process that could take 40 years or more.

Most importantly, the abbot was responsible for ensuring that salvation was ensured for all of of the monks under his authority. Salvation could only be achieved by undivided focus on God, achieved by adhering to the Order’s rules, including obedience, commitment and remarkable self-discipline. Individual breaches of internal order would be profoundly disruptive to the community as a whole and, depending on the nature of the transgression, could place the individual’s soul in jeopardy. Even the most dedicated and devout might find frustrations and difficulties associated with such a life. Maintaining strict discipline, albeit with compassion, empathy and care, was of fundamental importance for a community that lived together, usually for life, and the abbot was responsible for the wellbeing of both individual monks and the community as a whole, the father of his community.

Salvation. God seated in glory with angels to either side, proclaims salvation; the archangel Michael fights the 7-headed dragon as devils are hurled by other angels from the sky. From the Cistercian Abbey of Citeaux. Source: Wikipedia

The abbot was also responsible for the welfare of the monastery’s finances and its economic self-sufficiency. Each abbey received land and associated assets to ensure that it was self sufficient, but these resources did not manage themselves and, with assistance from key obedientiaries, the abbot was responsible for ensuring that the abbey achieved ongoing financial security. Obedientiaries, monks with specific roles within the community, were each allocated a budget to finance their particular area of responsibility, and the abbot would have been responsible for overseeing how to allocate funds, and how these individual budgets, once allocated, were employed. The running of a monastic establishment was equivalent to running a business, and the abbot was its managing director.

Each year, abbots were obliged to proceed to the heart of the Cistercian order, the New Monastery at Cîteaux, to attend a meeting called the General Chapter, which discussed matters of policy, changes to the rules and statutes, and disciplinary matters and ensured that standards were maintained. Sometimes abbots at lesser abbeys such as Cymer near Dolgellau, or abbeys going through economically rough patches, were forced to borrow the funds required for this long trip, which might place a heavy burden on the economic resources of the monastery.

Abbots of Valle Crucis

The abbey took its tone from the abbot, and there were both successes and failures recorded at Valle Crucis. Nothing much could be done about the war waged by Edward I on the abbey’s properties, and although reparations were made by Edward twice in the late 13th Century, the financial constraints and perhaps even some privation within the community may have been felt. It would have been the job of the abbot at that time of these and other difficulties to mitigate the impacts of the worries and any challenges that the abbey experienced.

There are no likenesses of any of the abbots of Valle Crucis, with the possible exception of a stone effigy that may have been Abbot Hywel, shown below and discussed further in part 5. The Cistercians did not believe in adorning their monasteries with art works, and even though later Cistercian abbots might have indulged themselves with portraits, during the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry VIII commanded that all the assets of the monasteries be sold or destroyed. Only a few Cistercian portraits therefore survive, and none of them were from Valle Crucis.

Sculpted face at the far end of the slype. Source: Wikimedia

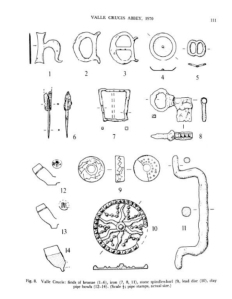

Valle Crucis, founded in 1201 with monks and an abbot, Abbot Philip, from Strata Marcella, received an annual visitation from the abbot of Strata Marcella, or his proxy, throughout its life to ensure that it was conforming to the rules and values of the Cistercians. Nothing is known of Abbot Philip, except that his appointment as abbot of an important new house marks him out as a highly responsible and suitably motivated individual, in all ways suitable for the daunting task of bringing up a monastery and its economic infrastructure from scratch. Certainly the architectural development of the abbey argues that Abbot Philip was very capable in at least that respect, but a statute issued early in his tenure refers to him rarely celebrating Mass or receiving the Holy Eucharist. He was apparently not alone, as the Abbots of Aberconwy and Carleon were also found guilty of the same lax behaviour.

There is mention of an an Abbot Tenhaer in 1227 and again in 1234. Nothing about him is known, but three dates tie in roughly with his tenure. In the mid 1225 and 1227 Valle Crucis was recorded as being in dispute with neighbouring monasteries Strata Marcella and Cwmhir respectively, probably in connection with grazing rights. In 1234 the General Chapter recorded that the incumbent abbot had allowed women to enter the monastic precinct. The name of the abbot is not given, so the guilty party could have been either Tenhaer or his immediate successor whose name is not recorded.

Between approximately 1274 and 1284 an Abbot Madog or Madoc is known, his name recorded in two notable documents. The first was a letter to the Pope in 1275, in which seven of the Welsh Cistercian abbots defended the reputation of Llywelyn against charges made by Anian, Bishop of St Asaph. The other six abbeys were Aberconwy, Whitland, Strata Florida, Cwmhir, Strata Marcella and Cymer. Valle Crucis is recorded in the same year as having only 5 monks. The second document is a document dating to December 1282, which notes a loan from Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffud of £40.00 to “expedite and sustain Abbot Madog” on abbey business. That was a substantial sum – the National Archives Currency Convertor estimates that today this would equate to £27,762.78 (or 47 horses, 88 cows or 173 stones of sheep wool). It may well have had something to do with Edward’s two major assaults on Wales in 1277 and 1282–83 respectively. Edward’s generous compensations to Valle Crucis and other northern abbeys indicate the level of damage inflicted on the monastic establishments, allocated to Valle Crucis in 1283 and 1284 (£26 13s 4d and 160 respectively – the latter the highest sum paid to a Welsh Cistercian monastery).

Fragment of a gravestone, possibly from Valle Crucis and perhaps showing Abbot Hywel. Photograph by Professor Howard Williams. Source: ArchaeoDeath blog

An Abbot Hywel is mentioned in February 1294 and July 1295. The dates tie in with a record showing that Edward I placed the estates of Roger of Mold in the care of the abbey in 1294 (whilst Roger was on Crown work in Gascony), and then visited in person in in 1295, making oblations (religious gifts) of “two cloths.” It is possible that he is the same Hywel Abbas shown in the fragment of a gravestone effigy showing a tonsured monk, first recorded in 1895 and now in Wynnstay Hall near Ruabon, which was on loan for a period to Llangollen Museum. A photograph of the effigy is shown left. Professor Howard Williams and colleagues have researched the fragment, the style of which is consistent with the late 13th century, and believe that it probably came from Valle Crucis. Whilst it may have been one of the choir monks, the investment in the carving of the slab argues that it was someone of more importance.

Abbot Hywel was succeeded by a number of abbots about whom, again, almost nothing is known, but in 1330 Abbot Adam was appointed and is apparently mentioned on several occasions until perhaps January 1344. It is thought that the inscription that remains clearly visible on the rebuilt gable on the west façade of the abbey church belongs to this abbot, claiming credit for the restoration work. His inscription was not consonant with Cistercian ideas of modesty and humility, but this type of autograph was by no means unknown in the Cistercian Order.

St Asaph Cathedral, which dates back to the 13th Century. Source: Wikipedia

Again there are some names or partial names recorded, but this was the period of the Black Death that arrived in 1349, when keeping up to date records was probably the last thing on most people’s minds, and it is not until Abbot Robert Lancaster that more details are again available. Abbot Robert was installed as abbot of Valle Crucis in about 1409, the year in which the papacy was reunited under pope Alexander V after the Great Schism of 1378. Shortly afterwards he was elevated to the bishopric of St Asaph. He held the positions of Abbot and Bishop simultaneously, until September 1419. His is an interesting case, although not unique. In that same year, 1419, a petition to the pope records that he had undertaken repairs to the monastery following a fire possibly inflicted during the Owain Glyndŵr rebellion. Another extension to his twin role was granted In June 1424 for another fifteen years. The conflicting demands of St Asaph and Valle Crucis may have tested his leadership skills because there is papal correspondence to the monastery, reminding the monks of their vows of obedience to the abbot, implying that there had been at least one serious breach of discipline or a challenge to his authority. Abbot Robert may have retained the abbacy of Valle Crucis up to the time of his death in March 1433. It is somewhat ironic that 6 generations on from Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor, the founder of Valle Crucis, the damage inflicted on the abbey during the Welsh rebellion between 1400 and 1410, was lead by Madog’s own descendent Owain Glyndŵr. This time, there was no compensation, and it is not known how Valle Crucis, under Abbot Robert, was able to fund its own recovery.

The English Richard or John Mason held the position of abbot, for a period period lasting between February 1438 and July 1448, which may have been a period of neglect, although the evidence for this has not been clearly stated. Abbot Mason was English, which may have caused difficulties within a Welsh context. Although 18 years after the end of Owain Glyndŵr’s rebellion, nearly a generation on, there must have been residual resentment and a sense of loss amongst the Welsh gentry of Powys Fadog, if not amongst those monks of the Valle Crucis community who retained a sense of Welsh identity.

Sculpted head at the far end of the slype. Photograph by Llywelyn2000 Source: Wikimedia

There is a gap of some seven years in the records, but the three abbots that followed, Sîon ap Rhisiart (John ap Richard, 1455-1461), Dafydd ab Leuan ab Iorwerth (1480-1503) and Sîon Llwyd (John Lloyd) seem to have engineered a turnaround in the fortunes of the abbey, which now came under the patronage of the Stanley family who have been discussed above. Under these abbots, Valle Crucis became a centre for literature and poetry. At the same time, it seems to have become a rather more gregarious establishment than in previous centuries, entertaining high profile guests in fairly lavish style, praised in verse by Welsh poets Guto’r Glyn, Gutun Owain and Tudur Aled.

Abbot Sîon ap Rhisiart (John ap Richard) was abbot between c.1455 and 1461. David Williams refers to him as an “abbot-restorer,” who was from an important local family, the Trefors. He is best known for the enthusiasm with which his hospitality was received by the poet Gutun Owain who described Valle Crucis as “a palace of diadem.”

Abbot Dafydd ab Leuan ab Iorwerth seems to have become abbot in February 1484. He may have come from the Aberconwy monastery, and was again a member of the important local Trefor family. He too was being praised by the Welsh poet Gutun Owain for his hospitality, commenting, with hindsight somewhat ambivalently “how good is the lord who loves to store his wealth and spend it on Egwestl’s noble church.” Owain also praised Dafydd’s architectural achievements, including a fretted ceiling in the abbot’s house. The village of Egwestl was the one that Valle Crucis had supplanted, and the abbey was still known locally by the village name. Abbot Dafydd became deputy reformator of the Cistercian Order in England and Wales in 1485, a position of considerable importance. Between 1500 and 1503 he was raised to the position of Bishop of St Asaph in Wales which, like Abbot Robert Lancaster earlier in the same century, he held concurrently (in commendam) with the the abbacy of Valle Crucis. He died in about 1503.

Abbot Sîon Llwyd (John Lloyd) became abbot in about 1503 and stayed in the position until about 1527. He became one the overseers of the compilation of the Welsh pedigree of Henry VII, a royal appointment, and in 1518 he was described as “king’s chaplain and doctor of both laws.” Like his two predecessors, he was praised in verse for his hospitality by a well known poet, this time Tudur Aled. Although he was buried at Valle Crucis, his tombstone was moved after the suppression and placed outside the church of Llanarmon yn Iâl.

Henry Fitzroy, duke of Richmond and Somerset, and patron of Valle Crucis during the abbacy of Robert Salusbury and during the dissolution of the abbey. Source: Wikipedia

Unfortunately but interestingly, this relatively brief period of glory was followed by disgrace. The richness of the abbey in its late years, and its comfortable lifestyle, seems to have attracted quite the wrong sort of abbot, of which more in the next post. The member of a local family was appointed to the post of abbot, although it is far from clear how he was able to obtain the position. The family was prominent and well respected, but Abbot Robert Salusbury, who held the position from 1528-35 has been implicated in a number of crimes and felonies and appears to have had no training as a monk. As Evans puts it (Valle Crucis Abbey, Cadw 2008): “He was a totally unsuitable candidate, who appears to have been imposed upon the abbey; he was probably under age, never served a proper novitiate as a monk, and does not seem to have been properly professed or elected.” Five monks left, leaving just two behind, forcing Robert Salusbury to acquire seven more from other monasteries, who he paid to serve. In February 1534, with matters clearly out of control at the abbey, Henry Fitzroy, duke of Richmond and Somerset, Lord of Bromfield and Iâl, and patron of Valle Crucis, sent a visitation (inspection) to Valle Crucis, headed by Abbot Lliesion of Neath (reformator of the Cisternian order in Wales), and accompanied by the abbots of Aberconwy, Cwmhir and Cymer. Things were soon set in motion for change. In June 1534, the abbey was put under the care of the Abbot of Neath. in 1534, assisted by the prior Robert Bromley. Salusbury was sent to Oxford for re-education, with a generous allowance, but the order’s good intentions were wasted. Salusbury was eventually imprisoned in the Tower of London for leading a band of highwaymen in Oxford.

Abbot John Herne/Heron/Durham had the unenviable task of succeeding Robert Salusbury. He had been a monk of the Abbey of St Mary Graces, Smithfield, London. It must have been something of a culture shock transferring from one of the Cistercian order’s few urban locations to the rural splendours of Valle Crucis, especially as he found the finances in such a poor state that he was forced to borrow £200 to meet the expenses of his own installation. He was abbot of Valle Crucis from June 1535 until August 1536. He was abbot when the Valor Ecclesiasticus, Henry VIII’s valuation of all the abbeys in the realm, was carried out. All monastic establishments valued at less than £200.00 were listed for immediate suppression and and the abbey was closed accordingly in 1536. Henry Fitzroy, patron of Valle Crucis, died in the same year, at the age of 17. After the suppression of the abbey, it is recorded in March 1537 that Abbot John was granted a pension.

fsdfasdf

Priors and sub-priors

The opening page of the Valor Ecclesiasticus, showing Henry VIII. Source: Wikipedia

The prior was secondary only to the abbot, was usually promoted from within the abbey’s own ranks and could rise to abbot of the same or another establishment, particularly a new, daughter establishment.

The only prior to receive attention in records associated with Valle Crucis is Prior Robert Bromley, who had been at Valle Crucis since about 1504 was passed over in favour of Robert Salusbury in 1528, a clearly very bad decision. Williams says that he was given several privileges, perhaps as compensation for being passed up for the abbacy in 1528: “He was now absolved from ecclesiastic censure due (if any) for not wearing the habit; he was permitted (because of infirmity) to wear linen next to his skin, long leggings of a decent colour (the monks were normally hare legged beneath their habit, and a ‘head warmer’ under his hood; he was allowed to talk quietly in the dorter [dormitory] . . . . and to eat and drink in his own (prior’s) chamber” (The Welsh Cistercians, p.68). Such concessions were usually allowed only to the abbot. When Salusbury was ousted by the Abbot of Neath in 1534, it was put in Bromley’s care temporarily, but he had no desire to become abbot of such a neglected establishment. He too was a victim of the Valor Ecclesiasticus, and was respectably pensioned off.

fsdfasdf

Final comments on part 4

As I was trying to untangle the stories of Powys Fadog and Bromfield and Iâl with a view to determining how they impacted patronage of the monastery, and to see what sort of political world surrounded and incorporated the abbey, it became increasingly clear why there were peaks and troughs in its career. Whilst there were periods of investment in architecture and scholarly output, it was also clear, and perfectly understandable, that the abbey had been through periods of downturn and neglect.

The Black Death of 1349 raised questions in secular minds about the value of the clergy and of monastic prayer, whilst the Hundred Years War between 1337 and 1453 and the Great Schism of 1378-1409 inevitably challenged more than the idea of a unified Cistercian identity, placing Britain and France (the homeland of the Cistercians), in opposing camps. For the entire period of the Great Schism, the annual General Chapter at Cîteaux was cancelled, with a papal bull from Urban VI releasing the Cistercians outside France from their obedience to the abbot of Cîteaux. The General Chapter resumed in 1411, but the tone of Europe, the perception of the Church and the character of the Cistercian order had changed. It was during the late 14th and 15th centuries that the abbots of Valle Crucis became more worldly, less committed to the original ideals of either St Benedict or the earliest Cistercians.

The penultimate abbot, Robert Salusbury, was clearly a very poor decision, but demonstrates how both the abbey’s current patron, Henry Fitzroy, and the Cistercian order mobilized together to resolve the undoubtedly embarrassing problem. They might not have bothered had they known how soon their world was to come tumbling down.

Next

Part 5 is coming shortly, and will talk about the monastic community below the level of abbot and prior, and how the monks and their colleagues lived their lives. All parts are available, as they are written by clicking on the following link: https://basedinchurton.co.uk/category/valley-crucis-abbey/

fsdfasdf

Sources for part 4:

Tying in various bits of data would have been a lot more difficult without the excellent Monastic Wales website, a brilliant resource for all monastic establishments in Wales, which lists a number of abbot names mentioned in documents, highlighting gaps in the sequence and allowing a clear impression of what is and is not known about both the abbey and its abbots. I used this as my starting point for reading about the personnel at Valle Crucis. As usual, The Welsh Cistercians by David Williams (2001) and the booklet Valle Crucis Abbey by D.H. Evans (2008) have been invaluable.

All sources for the series are listed in part 1.

Swallow mentions that Castletown Bridge, which carries the road across the stream between the two castles, “was probably the site of the medieval toll gate, catching people and animals entering Cheshire from Wales to the south and west, as Shocklach castle guarded the only road into Cheshire at this point.” Documentation suggests that a toll gate was present there

Swallow mentions that Castletown Bridge, which carries the road across the stream between the two castles, “was probably the site of the medieval toll gate, catching people and animals entering Cheshire from Wales to the south and west, as Shocklach castle guarded the only road into Cheshire at this point.” Documentation suggests that a toll gate was present there