Introduction

Either side of the River Dee, and linked by the lovely late medieval red sandstone bridge, are the villages of Holt on the Welsh side and Farndon on the English side, each with its own substantial red sandstone church, both of which are dedicated to St Chad and both of which have well-populated churchyards. Each has its own very particular character and personality, and as well as being the centres of Christian devotion and burial, seamlessly blending life and death, both have Civil War stories and scars and both continue to function as places of worship today. This post is about the Grade-1 listed St Chad’s in Holt.

Map showing the location of Mercia and the line of the Anglo-Welsh border. Source: Wikipedia

The church is located at the top of the slope that runs down to the river crossing, precisely where Bridge Street meets Church Street, opposite the small rectangular green. An attractive wrought iron gateway is set between a house on one side and the Peal O’ Bells pub on the other, and opens onto a path flanked by red sandstone garden walls leading to the church and churchyard. The church is light-filled with a peaceful atmosphere and some notable features, some of them very unusual. The overall effect of St Chad’s is welcoming and combines a sense of heritage with contemporary relevance. For details about visiting, see Visiting Details at the end.

According to Bede (in the 8th century) St Chad, who died in AD 672, was a leading light in the Anglo-Saxon church, rising through the ecclesiastical ranks in the kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia and under King Wulfhere, one of the earliest Christian kings, became the first Bishop of Lichfield in the new diocese of Lichfield, at the heart of Mercia. Mercia was one of seven British kingdoms of 7th century Britain and occupied most of central England, with much of the border with Wales, always a movable feast, somewhat further to the west. Regarded as a pioneer who helped to spread Christianity in and beyond Mercia, he became popular during the Middle Ages in the Midlands and its borders.

The following details are just the edited highlights. For a more technical architectural description see the Wrexham Churches Survey (see Sources at the end). The church very much rewards a visit.

xxx

Exterior

South side of St Chad’s Church, Holt

The church is approached through a pair of wrought iron gates that were made in 1816 and replaced the former lychgate. As you approach the church and walk around to find the carvings around the south door, you will notice a change underfoot because in the immediate vicinity of the church the path is composed of horizontal ledger grave stones and vertical headstones laid flat (distinguished by chisel marks at the bases, which would have been underground), all forming huge paving slabs, some from the 18th century.

Path made up of grave markers

The exterior of the church is built of local red sandstone, the older parts badly eroded on the exterior, probably as a result of traffic pollution. Sandstone, being soft, lends itself to graffiti and there is quite a lot of it dotted around the building, dating from the 18th century. The roof of the rectangular nave and chancel is made of copper, which accounts for its green colour. Copper was more expensive than the more usual lead, and is both fire resistant and more enduring, as well as a gesture of status.

A curious feature of the church and its roof-level features is the presence of crocketed pinnacles, each with twin gargoyles on the north sides and the absence of them on the south side. I only noticed because I love gargoyles and go looking for them. This is due to the removal of the pinnacles on the south side during 1732, one of the periods of redesign and alteration.

North side of the church, showing four pinnacles, each of which is adorned with small gargoyles. Photograph taken from the west, just next to the tower.

The tower features four gargoyles on the corners at the very top of the tower, and a string-course just below that level marked by floral ornamental motifs and small grotesques, very similar to the sculpted string-course that you can see here at Gresford All Saints’. The 18th century bells are referred to below. The top of the tower has gargoyles at its corners and the roof of the tower appears to be leaded.

The string course of grotesques, flowers and other motifs near the top of the tower.

A circuit of the exterior reveals that there are three doorways. The studded west door, through which visitors enter today, is impressively large, but has no notable features.

A circuit of the exterior reveals that there are three doorways. The studded west door, through which visitors enter today, is impressively large, but has no notable features.

The earliest entrance is the south door, with some lovely, albeit very eroded ornamental carvings. This would have been the main access from the castle, which is why it was so ornate. As well as decorative motifs, there is a central panel showing the Annunciation set over the top of the arch and carvings in the spandrels (the three-sided sections between the arch and the square frame). The spandrel on the right as you face the door shows the arms of Henry VII, together with a figure wearing a mitre; the other side is very worn. Above the door and its surround is a carved band of small quatrefoil motifs, each arranged in patterns of four. xxx

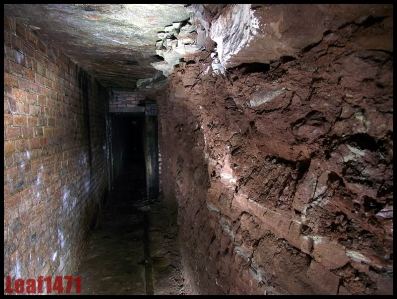

The door that opens into the north aisle of the church (round to the left of the tower as you face it) has nice carved details in the spandrels between the arch and the square frame. Most fascinatingly, it has a line of three holes in it plugged with wooden stoppers. These holes are called loopholes and were used for firing muskets from inside, much like arrow-slits in medieval castles.

The north entrance with the “loop holes.”

At the east end, under the central window, is an unusual little memorial built into the wall to Jasper Peck Esq and his wife Amy, died 1712 and 1740 respectively, the latter the daughter of Sir Kenrick Eyton.

At the east end of the church, built into the external wall beneath the central window, is an 18th century memorial

A memorial in the churchyard of St Chad’s, Holt

The churchyard contains plenty of grave stones and memorials. The earliest, now moved for its protection inside the church (about which more below) dates to either the late 17th or early 18th century. Although there are many from the 18th century, the majority of graves and their memorials date to the 19th century, with a range of fairly typical shapes and symbols. Most of the memorials accompanying the graves are headstones, but earlier chest-style memorials and ledgers (inscribed horizontal slabs) are also represented, together with more obviously monumental types. The cemetery was later extended east, possibly in an effort to avoid the north side of the church, which only has one gravestone, and even that is at the far east end. The north side of a churchyard, in the shadow of the church, was often reserved either for burials that had to be buried in unconsecrated ground, such as suicides or babies who had died before baptism, but might also contain pauper and unmarked graves. The monument known as the Roman Pillar, shown further down the page, may or may not have originally been a Roman column from the nearby tileworks, but in the churchyard performed the role of a sundial, now without a dial, with an octagonal top with the engraving TP WR CW 1766.

xxx

Interior

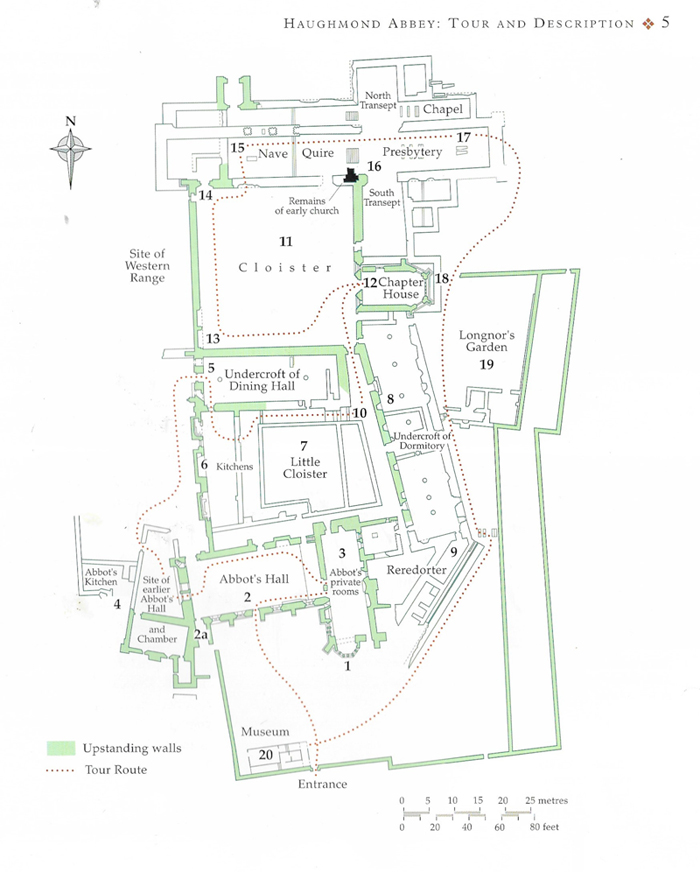

The plan of St Chad’s is simple, with the tower at the west end, and the chancel (where the high altar is located) at the east end as usual. The nave, where the congregation sits, is flanked by two aisles. The chancel is flanked by two chapels for private prayer.

The roof looks as though it belongs to the Perpendicular period, but is belongs to the restoration of 1871-3

Heading through the impressive main door, set into the base of the tower, and through the glass-panelled doors into the nave, you are immediately presented with an uninterrupted view down the full length of the tall nave towards the east end. The multiple large windows, only one of which has stained glass (dating to the early 1900s), provide the interior with a lot of natural light, even in the absence of clerestories. The arcades are made of a fine yellow sandstone, much better than red sandstone for creating a light space, and much more refined in appearance. The warm, light reddish wood of the relatively modern pews helps to add to avoid any sense of dourness. The walls lack the usual distracting and overblown clutter of highly ornamental wall memorials. Looking up, the wooden ceiling looks as though it belongs to the Perpendicular period, but is belongs to the restoration of 1871-3.

Inevitably there is a bank of 1910 organ pipes blocking the south aisle, shutting out light and preventing direct access from the north aisle to the north chapel, but this is entirely typical, echoing the same scheme in both Gresford and Malpas churches, amongst many others. Similarly, the south aisle is truncated at the western end of the aisle by a small room presumably used as a vestry.

The 13th and 14th Centuries

Holt Castle by Peter Mazell in 1779. Source: Castle Studies Trust

There is no evidence of a church prior to the 13th century. The village of Holt was built in the early 1280s, probably as a bastide by John de Warenne, the 7th Earl of Surrey under a charter from Edward I. A bastide was a newly laid out pioneer town built around a castle on the edge of potentially hostile territory. Edward I imported the idea imported from Gascony where he had founded a number of new defended towns, and used it as a model for Flint Castle and its bastide town, as well as subsequent castles in his circle of defences in north Wales. Defensive walls may have been planned for the town but were never built. The foundations of the first church were probably included in the plan for the border colony, along with a former marketplace (where the village square is located today).

The earliest remaining components of the present church belong to the 13th -14th century. The nave arcades (arches that divide the nave from the aisles) feature five bays of lancet-shaped pointed arches that date to this period and indicate either that the original church of c.1280 was aisled, or that aisles were a later 14th century addition. The aisles were widened in the 15th century, removing the older aisle outer walls, but the original ones almost certainly featured lancet-shaped windows of the earlier gothic “Decorated” style.

The earliest of the aisle arches are pointed (or lancet) shaped, unlike the later Perpendicular arches that flank the chancel.

An attractive 14th century “credence table,” looking like a small shrine, was built into the south wall of the Lady Chapel at the east end of the south aisle, moved into this position in Sir William Stanley’s alterations in the late 15th century. This was used for accessories used to celebrate Holy Mass. The underside, completely hidden when looking down onto the small platform, has a marvellous grotesque face flanked by two faces, one human and one animal, looking very like a misericord. If there were misericords in the late medieval choir, like the lovely ones at Gresford, these are long gone. A mirror leans against the wall but can be laid flat for those who want to see the underside without kneeling down.

Unexpected underside of the credence table, looking very like a misericord

Late 15th Century

In 1483 Richard III granted the Lordship of Bromfield and Yale to Sir William Stanley, which incorporated both Holt Castle and the church. Stanley made significant changes to the church, removing and replacing the outer walls of the original aisles to widen them, providing them with the Perpendicular style windows, and extended the arcade at the east end. For reasons unknown, the north aisle is wider than the south aisle. The south aisle chapel is a Lady Chapel. The little leaflet that the church provides suggests, with reservations, that that the chancel, which is slightly out of alignment with the nave, may have been a so-called “weeping chancel,” deliberately and symbolically echoing the images of the crucifixion where Christ’s head is tiltee down to his right.

At the chancel, the two bays of arcades flanking the chancel (the choir and high altar), have much wider four-centred (flattened) arches, providing a very fine contrast to the earlier lancet-shaped arches. The new arcades were fitted with carved stone heads at the tops of the east and west walls, all but three undetermined male heads. The other three consist of one male head that is crowned and is probably a king, another depicting a dog and another a grotesque face.

At the chancel, the two bays of arcades flanking the chancel (the choir and high altar), have much wider four-centred (flattened) arches, providing a very fine contrast to the earlier lancet-shaped arches. The new arcades were fitted with carved stone heads at the tops of the east and west walls, all but three undetermined male heads. The other three consist of one male head that is crowned and is probably a king, another depicting a dog and another a grotesque face.

There were apparently problems with the civil engineering of the new east arcade. The last of the free-standing arcade pillars in the south aisle is at a distinct angle, and there is a pillar at the east end, against the wall, which does not reach the roof, as described on the Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust / Heneb website: “To explain anomalies at the east end of the south aisle it has been suggested that because the east window of the aisle was too large for the wall to support, an external buttress had to be placed nearer to this window than was planned. An internal pillar was then constructed where the exterior buttress should have been sited.”

Mitred figure at St Chad’s, Holt

The tower at the west end, through which you enter the church, has a spiral stair case to the bell tower (closed to the public). As you go into the nave from the tower, look right. There is a carving of a figure wearing a mitre, which is a fragment of a medieval bench-end of the sort that you can see in the choirs at Chester Cathedral and Gresford All Saints’, and suggests that there was once some very interesting Gothic wood carving here. The mitre is consistent with it representing St Chad, but other candidates are also entirely plausible. During 19th century restoration work the head was removed from the church and for reasons unknown found itself at Holt Hall, where its dignity was severely undermined, having been employed as a newel post. Holt Hall was one of the many of the fine buildings that failed to survive the early 20th century, and when it was taken down in the 1940s the head was returned to St Chad’s.

Also at the west end to the right as you enter the church, in the south aisle, is the wonderful font, elaborately and deeply carved and dated by Edward Hubbard to c.1493 on the basis of the heraldry that appears in amongst the other carved panels. It is a truly remarkable object, featuring the above-mentioned heraldic emblems, religious symbols and even a number of grotesques. The heraldic symbols include a stag’s head, which is one of the emblems of Sir William Stanley and the others are the arms of previous lords of Bromfield, the Warenne and Fitzalan families as well as the heraldic shield of King Richard II (reigned 1452-85). Others are religious symbols showing emblems of Saints Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, the Lamb of God, the “pelican in her piety,” highly stylized roses representing the Virgin Mary and the ubiquitous gothic acanthus leaves.

The late 15th century font with a reconstruction from one of the interpretation boards showing how the shields may have been coloured

Sir William’s modifications represent a major investment and suggest enormous personal ambition, a desire to put his stamp on the biggest community asset in late medieval Holt. It did not save him from political manoeuvring. Although one of the richest men in England, Sir William Stanley was executed for suspected treason by Henry VII in 1495 and the Lordship of Bromfield and Yale reverted to the crown.

The 17th Century

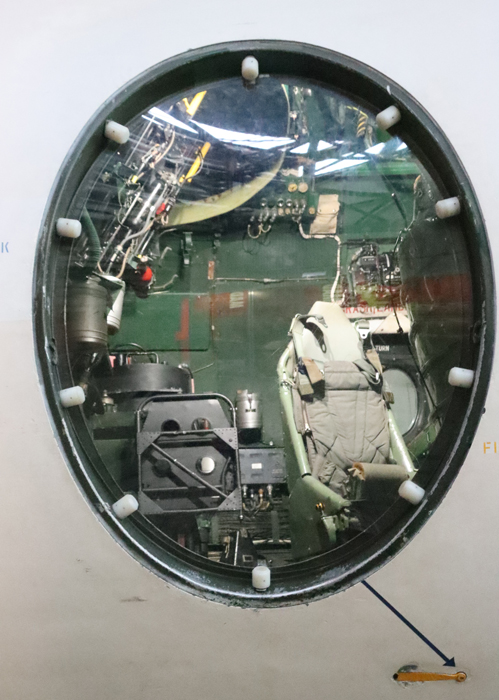

Musket ball holes in the west wall, south aisle of st Chad’s Church, Holt

The Civil War took place between 22nd August 1642 and 3rd September 1651, and had a massive impact on the Chester area, with opposing forces occupying Holt and Farndon at the strategic river crossing. Frank Latham sets the scene as it was in 1643: “Because of its prominence on a hilltop overlooking the river the parish church of Farndon was garrisoned by Roundhead troops from 1643 to 1645 which enabled watch to be kept on the Welsh village of Holt and particularly on the castle there which was occupied by the enemy.” With Farndon in the hands of the Parliamentarians and Holt in the hands of the Royalists, armed conflict was almost inevitable, and the Battle of Farndon Bridge in November 1643 appears to have been the beginning of a number of skirmishes. The castle was taken by the Parliamentarians, but in 1644 was retaken by the Royalists. In 1647 it was besieged for 9 months.

Fascinatingly, impact marks of musket balls scar the wall and pillars inside the west end of St Chad’s, which are an evocative reminder of the area’s troubled history at that time, when Royalist soldiers defended the church against the Parliamentarians, with hand-to-hand fighting taking place within the church itself. You can find these mainly on the west wall of the south aisle (turn right as you walk in from the tower and they are on your right), with a few on the other side as well. Don’t forget that the north aisle has a doorway with three “loop holes” through which weapons could be fired, only one of these can be seen from the interior, but there are also some marvellous lock fittings.

Finally, a very small and beautifully decorated late brass plaque in the north aisle chapel should not be missed. Its beautifully reflective surface made it impossible to photograph nicely. It is dedicated to Thomas Crue, who died in 1666. The plaque was provided by his brother Silvanus Crue. All of the imagery, with a skeleton flanked by skulls at its base, columns supporting sundials and hour glasses all reference time, death and the transition of the soul. On the columns the words FUGIT HORA also reference the passing of time: “time flies.” At the top, in the centre, a lion rampant stands over a grotesque head. As well as some lovely engraved mortuary-themed decoration, it contains an acrostic; when read vertically, the first letter of each new line makes up one or more words. In this case the vertical reading over two verses is THOMAS CRUE, and the full text is as follows (having performed some serious gymnastics to read it against the light):

Finally, a very small and beautifully decorated late brass plaque in the north aisle chapel should not be missed. Its beautifully reflective surface made it impossible to photograph nicely. It is dedicated to Thomas Crue, who died in 1666. The plaque was provided by his brother Silvanus Crue. All of the imagery, with a skeleton flanked by skulls at its base, columns supporting sundials and hour glasses all reference time, death and the transition of the soul. On the columns the words FUGIT HORA also reference the passing of time: “time flies.” At the top, in the centre, a lion rampant stands over a grotesque head. As well as some lovely engraved mortuary-themed decoration, it contains an acrostic; when read vertically, the first letter of each new line makes up one or more words. In this case the vertical reading over two verses is THOMAS CRUE, and the full text is as follows (having performed some serious gymnastics to read it against the light):

The life of man incessantly from the womb

Hastneth both day and night unto the tomb

Of mortal life when once the thread is spunne

Man has a life immortal then begunne

A wise man dying lives; and living dies

Such was the main that here intombed lies

Carefull he liv’d gods secret laws to keep

Religiously until to Death or Sleepe

Unto a happy life his soule did bring

Ending this life to live with Christ our King

At the base it reads STIPENDIUM PECCATI MORS EST is a Latin phrase that translates as “The reward of sin is death,” and with dry humour typical of the 18th century, HODIE MIHI CRAS TIBI translated as “Me today, you tomorrow”. All of this may sound a little gloomy and morbid, but this was the era of John Donne and equally articulate metaphysical poets who engaged with satire, dark humour and word play, balancing the reality of time and its inevitable consequences with a strong sense of irony and flamboyant wit.

The 18th Century

In the south aisle, heading towards the chancel and on your left, there is a super grave slab that was moved in from the churchyard to protect it. It is a marvellous piece, with a skull and crossed bones, the skull having a somewhat surprisingly beatific smile on its face. There are also some flowers at its base. The flowers at bottom left were apparently typical of the 18th century, but the skull and crossed bones were better known from plague graves of the 17th century, and are known as memento mori stones, indicating the inevitability of death.

In the south aisle, heading towards the chancel and on your left, there is a super grave slab that was moved in from the churchyard to protect it. It is a marvellous piece, with a skull and crossed bones, the skull having a somewhat surprisingly beatific smile on its face. There are also some flowers at its base. The flowers at bottom left were apparently typical of the 18th century, but the skull and crossed bones were better known from plague graves of the 17th century, and are known as memento mori stones, indicating the inevitability of death.

It is in this period that six bells were added to the tower, made by Rudhalls of Gloucester in 1714. Presumably, if there had been any misericords these would have been removed either during the 17th century purge of medieval religious motifs, or at this time, although at least parts of the choir stalls were reported to be preserved in 1853, but were stripped out in the 1870s. In 1720 the church was presented with a clock, which stayed in position until 1901. This was followed by significant renovation of the church in 1732, during which, very sadly, the the rood loft and screens were removed. This renovation also accounts for the parapet that replaced the pinnacles, gargoyles and battlements on the south side, although some were left in position on the north side.

A lovely engraved brass plaque near the entrance, on the west wall on the north side is worth looking out for, dedicated to John Lloyd and dating to 1784.

19th – 20th Century

The 19th century restoration between 1871 and 1873 was responsible for adding some of the ornamental features, such as the new seating in the nave and oak screens to separate the chancel from the side chapels, but also removed some of the memorial tablets from the walls. Restoration work included including the renewal of the camber-beam oak panelled roof of the nave and the sanctuary at the far end of the chancel, re-laying of the floors and repairs to the window tracery. Interestingly, many memorial tablets were removed during the renovation of the interior, which almost certainly improved it no end, but whatever remained of the rood screen and choir stalls were also stripped out. It is possible that choir stalls and some stained glass were removed at this time, as they were mentioned by a visitor in the early 1850s.

The 19th century restoration between 1871 and 1873 was responsible for adding some of the ornamental features, such as the new seating in the nave and oak screens to separate the chancel from the side chapels, but also removed some of the memorial tablets from the walls. Restoration work included including the renewal of the camber-beam oak panelled roof of the nave and the sanctuary at the far end of the chancel, re-laying of the floors and repairs to the window tracery. Interestingly, many memorial tablets were removed during the renovation of the interior, which almost certainly improved it no end, but whatever remained of the rood screen and choir stalls were also stripped out. It is possible that choir stalls and some stained glass were removed at this time, as they were mentioned by a visitor in the early 1850s.

The interior ceiling corbels that support the camber beams were provided with sculptural elements, all human heads. You will need binoculars or a long camera lens to see them, high up and in shadow, but a couple of examples are shown here. There is no mention of them in any of the texts, so it is unclear if this dates to the major reworking during the 15th century, or to the 19th century restoration and reconstruction of the ceiling.

Nineteenth century restoration activities can often result in some hair-raising alterations, but St Chad’s seems to have got off quite lightly, retaining some fine original features. The attempts to restore some of the original ambience were fairly sympathetic, and the new features were not unattractive. As nineteenth century restorations go, it was not unsuccessful.

In 1896 the bells were provided with a new iron frame and the following year a weathervane was added.

The single stained glass window in St Chad’s, Holt. Early 20th century.

Since then, the main additions to the church have been the new clock in 1902 and a stained glass window later in the early 20th century. The new clock and chimes were fitted to commemorate the coronation of King Edward VIII and Queen Alexandra in 1902. The stained glass window consists of four panels depicting saints. The two central panels show St Chad holding an image of the church in his hand, and St Asaph (the church is in the diocese of St Asaph). The outer panels show St David, the patron saint of Wales and St Swithin, reflecting an older connection with Winchester Cathedral in 1547. It is very nicely done for a 20th century window, emulating the gothic and works well with the rest of the church’s features.

In the 1960s the lighting and heating were improved and the roof coverings were restored.

Detail of Victorian pulpit, St Chad’s Holt

Uncertain dates

It is not known for sure when the tower was built. One authority puts it in the 17th century, but it is more likely that is is much earlier, probably late 15th century.

It is not known for sure when the tower was built. One authority puts it in the 17th century, but it is more likely that is is much earlier, probably late 15th century.

Probably late medieval, but not officially dated, are consecration crosses, one of which is next to the radiator to the right of the credence table, and there are other similar consecration crosses marking places that have been consecrated by a member of the clergy elsewhere in the church.

There is a magnificent chest not far from the west end, which had four locks, each representing a keyholder who had to be present when the chest was opened. This has not been dated, but realistically looks as though it could date to any time between the late 15th to the 17th century.

xxx

Chest in St Chad’s, Holt

Today

There has also been some modernization to improve lighting and heating, which were probably much-needed. The pipework for the heating system is fantastic – a remarkable feature in its own right, just as the heating system in Chester Cathedral makes its own contribution to domestic-industrial history.

A replacement sandstone block interrupting some engraved text on an external wall of the church

Obviously the church requires ongoing maintenance. Sandstone is very vulnerable to pollution, and some of the blocks have had to be repaired using modern sandstone, but thanks to the church being set back from the road this is minor work. It also looks as though some of the four gargoyles on the tower have experienced some damage, but that too is inevitable. Overall, St Chad’s seems to be in really excellent condition and is clearly well cared for and appreciated.

The church organizers seem to be doing a very good job of balancing the contrasting demands on St Chad’s. As well as the provision of plenty of information for visitors about the history and heritage of the church as a tourist attraction, the church is managed as a community asset for services, weddings, funerals and community activities. Reflecting a concern with modern global issues, there are four “millennium banners,” made by members of the congregation to welcome in the year 2000, which capture local scenes but represent the universal ideas of love, hope, peace and faith.

Visiting St Chad’s, Holt

The “Roman pillar”

There is currently no dedicated website, so there is no generally available online information about opening times. I was able to walk in during the day one bank holiday Monday on a whim, and found it open. On the other hand, I was there some months later at around 1230 on a Wednesday and it was closed, but I found that it had opened later in the afternoon. There is a Facebook page but it has no details about opening times and contact details. Please note that the email address on the National Churches Trust page bounces (i.e. it is defunct). This is a living church, with Sunday services, weddings and funerals, so even if you do find out what the opening times may be, there will be times when it is not possible to gain access.

There is plenty of parking along the road, but there is also a public car park just a few minutes walk away on the other side of the rectangular grass area, Church Green, on the other side of the road from the church. There is a car park next to the Dee on the Farndon side, but this is very small and fills up quickly at the weekend and during the school holidays, and floods when the river is up.

One of the bilingual interpretation panels in the church, describing the early development of the town

Information boards and circular panels on short pedestals explain the heritage of the church and are nicely done and for the most part do not intrude on the look and feel of the church. A small black and white leaflet was available on the table to the right in the tower as you walk in, consisting of two sides of A4, folded, that lists the key features to see in the church.

For those worried about steps and accessibility, the church can be visited without having to negotiate any obstacles, as there is a ramp from the tower into the nave. There are plenty of pews for giving irritable legs a rest. Outside, there is a wide path that runs along the south side of the church and a narrower one along the north side and these both felt safe underfoot. There are also tracks through the churchyard, but if you are looking for a particular grave, note that the grassy spaces between graves are very uneven and you need to take seriously good care where you place your feet. I suspect that it gets very muddy during rainy periods, so appropriate footwear is recommended.

This would make an excellent start or finish to a walk along the River Dee, which has footpaths on both sides of the river. The late medieval bridge is itself a joy. On the Holt side a visit could easily take in Holt Castle as well and on the Farndon side there is, of course, the other St Chad’s. There’s a pub next door to the Holt church that advertises food and a garden, which I haven’t yet tried, but might be handy for the end of a walk. There are other pubs and coffee shops on both sides of the river, all serving food.

————-

Sources:

Visitor information in St Chad’s, Holt

Interpretation boards and panels

Free leaflet: 20 Minutes of Discovery Around St Chad’s Church Holt

Books and papers:

Farmer, David 2011 (5th edition). Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford University Press

Hubbard, Edward 1986. The Buildings of Wales. Clwyd (Denbighshire and Flintshire). Penguin Books and University of Wales Press

Latham, Frank. 1981. Farndon: the History of a Cheshire Village. Farndon Local History Society

Websites:

Archaeodeath

Skulls in Stone and Brass: Inside Holt Church

https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2015/08/25/skulls-in-stone-and-brass-inside-holt-church/

Masters of Holt

https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2015/10/09/masters-of-holt/

Based In Churton

Big and bold: All Saints’ Church in the small village of Gresford

https://wp.me/pcZwQK-43a

Gresford All Saints’ Church – exterior gargoyles and grotesques

https://wp.me/pcZwQK-498

Gresford All Saints’ Church – a beginner’s guide to funerary monuments

https://wp.me/pcZwQK-49Z

Miracles, myths, demons and the occasional grin: Misericords in the Chester-Wrexham area #2: The churches of Gresford All Saints’, Malpas St Oswald’s and Bebington St Andrew’s

https://wp.me/pcZwQK-4Ey

British Listed Buildings

The Parish Church of St Chad, Holt

https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/300001596-parish-church-of-st-chad-holt

Cadw

The Parish Church of St Chad, reference 1596

https://cadwpublic-api.azurewebsites.net/reports/listedbuilding/FullReport?lang=en&id=1596

Coflein

St Chad’s, Holt

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/165283/?term=holt&pg=2

(images at https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/165283/images?term=holt)

Holt Bridge; Farndon Bridge, Holt, Wrexham

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/24043/

Early Tourists in Wales

North side of the churchyard

https://sublimewales.wordpress.com/material-culture/buildings/churchyards/special-graves/north-side-of-the-churchyard/

CPAT / HENEB – Wrexham Churches Survey

Church of St Chad, Holt

https://heneb.org.uk/archive/cpat/Archive/churches/wrexham/16796.htm

or https://cpat.org.uk/Archive/churches/wrexham/16796.htm

National Churches Trust

St Chad’s, Holt

https://www.nationalchurchestrust.org/church/st-chad-holt

Peoples Collection Wales

St Chad’s Church, Holt

https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/435519#?xywh=0%2C-55%2C799%2C642

St Chad’s, Holt – Facebook page

https://www.facebook.com/pages/St-Chads-Church-Holt/102667013120267

xxx

One of the many heads at the tops of the aisle walls

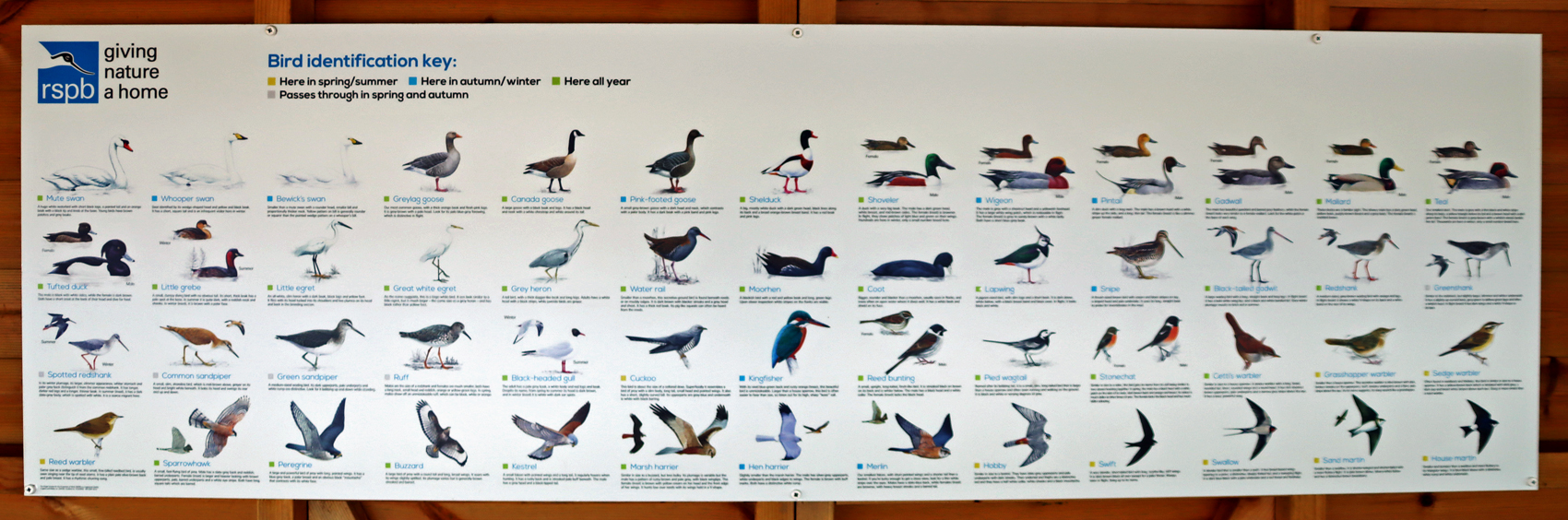

I have made a short visit to the estuary cycle track and walk in the past, simply to get a good look at the purported Iron Age promontory fort on Burton Point, but although it was enjoyable, it was a short stroll because the skies opened and I got drenched. Today, with no risk of rain, I decided to walk from Burton towards Parkgate, which I guessed to be about an hour’s walk each way. When I reached the “You are Here” board (with which the walk is dotted at key points) at Moorside, alongside Parkgate Spring and on the very edge of Parkgate, this was a full hour.

I have made a short visit to the estuary cycle track and walk in the past, simply to get a good look at the purported Iron Age promontory fort on Burton Point, but although it was enjoyable, it was a short stroll because the skies opened and I got drenched. Today, with no risk of rain, I decided to walk from Burton towards Parkgate, which I guessed to be about an hour’s walk each way. When I reached the “You are Here” board (with which the walk is dotted at key points) at Moorside, alongside Parkgate Spring and on the very edge of Parkgate, this was a full hour.

This first stretch of metalled lane is dominated by dog walkers and cyclists. Do keep an ear open for the cyclists as they can pick up a lot of speed along the lane and don’t always give a lot of notice of their impending arrival. The path goes through various changes. After some time it parts from the lane and becomes much more of a footpath with rough stone underfoot, which probably accounts for why the cyclists vanish from the scene at this point. At one stage it becomes a track across a field, although there is a route around this in wet weather that diverts inland for a while. The entire walk is well maintained with pedestrian gates and bridges where needed. One field had horses in it, so do take care if you are walking dogs.

This first stretch of metalled lane is dominated by dog walkers and cyclists. Do keep an ear open for the cyclists as they can pick up a lot of speed along the lane and don’t always give a lot of notice of their impending arrival. The path goes through various changes. After some time it parts from the lane and becomes much more of a footpath with rough stone underfoot, which probably accounts for why the cyclists vanish from the scene at this point. At one stage it becomes a track across a field, although there is a route around this in wet weather that diverts inland for a while. The entire walk is well maintained with pedestrian gates and bridges where needed. One field had horses in it, so do take care if you are walking dogs. Nearing Neston I spotted a line of vast red sandstone blocks extending out into the estuary vegetation, and a small spur of land also extends out at this point. An information board explains that this is part of the Neston Colliery, Denhall Quay. There is a particularly good book about the collieries, The Neston Collieries, 1759–1855: An Industrial Revolution in Rural Cheshire (Anthony Annakin-Smith, second edition), published by the University of Chester, which I read and enjoyed a few years ago. The sandstone blocks are massive, and as well as retaining original metalwork, one of them has become a memorial stone, as has one of the trees on the small spur of land. The line of sandstone, now a piece of industrial archaeology, is a very small hint of the extensive work that once took place here, but is an important one. The author of the above-mentioned book refers to it in a short online page here, from which the following is taken:

Nearing Neston I spotted a line of vast red sandstone blocks extending out into the estuary vegetation, and a small spur of land also extends out at this point. An information board explains that this is part of the Neston Colliery, Denhall Quay. There is a particularly good book about the collieries, The Neston Collieries, 1759–1855: An Industrial Revolution in Rural Cheshire (Anthony Annakin-Smith, second edition), published by the University of Chester, which I read and enjoyed a few years ago. The sandstone blocks are massive, and as well as retaining original metalwork, one of them has become a memorial stone, as has one of the trees on the small spur of land. The line of sandstone, now a piece of industrial archaeology, is a very small hint of the extensive work that once took place here, but is an important one. The author of the above-mentioned book refers to it in a short online page here, from which the following is taken: There are very few places to sit down along the walk, so I would recommend that if you need to rest your legs occasionally, you take your own portable seating. Regarding refreshments, I have mentioned Net’s Café, near the Burton end. I haven’t visited and apparently there’s no website, but it is just off Denhall Lane and it is listed on Trip Advisor here. There is also a very good pub called The Harp, which I actually have visited, with outdoor tables immediately overlooking the wetlands towards the Welsh hills, just outside Little Neston. The food being served there looked excellent, and I can give a solid thumbs-up for the cider. The pub was particularly well situated for my return from Parkgate as the zoom lens on my camera, a particular beauty that has been worryingly on the twitch for weeks, suddenly stopped working and was now, just to ram home the overall message, rattling. A glass of cider and a seat in the sun were perfect for jury-rigging the wretched thing so that the zoom now worked like an old-fashioned telescope and the camera’s autofocus, which was refusing point-blank to engage in conversation with the lens, could be operated manually on the lens itself. Sigh. New lens on order.

There are very few places to sit down along the walk, so I would recommend that if you need to rest your legs occasionally, you take your own portable seating. Regarding refreshments, I have mentioned Net’s Café, near the Burton end. I haven’t visited and apparently there’s no website, but it is just off Denhall Lane and it is listed on Trip Advisor here. There is also a very good pub called The Harp, which I actually have visited, with outdoor tables immediately overlooking the wetlands towards the Welsh hills, just outside Little Neston. The food being served there looked excellent, and I can give a solid thumbs-up for the cider. The pub was particularly well situated for my return from Parkgate as the zoom lens on my camera, a particular beauty that has been worryingly on the twitch for weeks, suddenly stopped working and was now, just to ram home the overall message, rattling. A glass of cider and a seat in the sun were perfect for jury-rigging the wretched thing so that the zoom now worked like an old-fashioned telescope and the camera’s autofocus, which was refusing point-blank to engage in conversation with the lens, could be operated manually on the lens itself. Sigh. New lens on order.