As I outlined in part 2.1, for part 2, just as in Part 1, I have again divided part 2 into two posts, 2.1 and 2.2, mainly because of the number of images used, which would take too long to load if I left it as a single piece. This is the second part of part 2, part 2.2. Part 2.1 is here.

xxx

xxx

Insights from the annual Visitor and Superintendent Reports for 1854-1870 contd.

Patients and their backgrounds

In the annual reports, patients are largely reduced to numbers. Without exception the reports never give personal names of patients, only rarely referring occasionally to specific individual cases, such as suicides, escapes or, as in 1857, the birth of a child, and there are only a few clues in the annual report about who these people were. One of the vital tables in this respect, which always appeared in the annual report, showed the occupations of each of the admissions for each year. Given that this was mainly an asylum established for paupers, it is not surprising to find that most of the intake was from the lower-paid levels of Cheshire society, but the term “pauper” when applied to asylum patients did not always refer to very poor people. The term “pauper” covers a range of people. Some were genuinely very impoverished, such as those transferred from workhouses, but others might be fully employed but without sufficient funds for their families to afford asylum costs. This is probably one reason why there is a wide range of trades and professions represented, partly representing Chester’s diverse economic basis. The variety of occupations might be more mixed when private patients from middle class families were admitted, or when patients were transferred from other asylums such as Staffordshire and Denbigh. Two examples are shown below, one from 1855 and another from 1870.

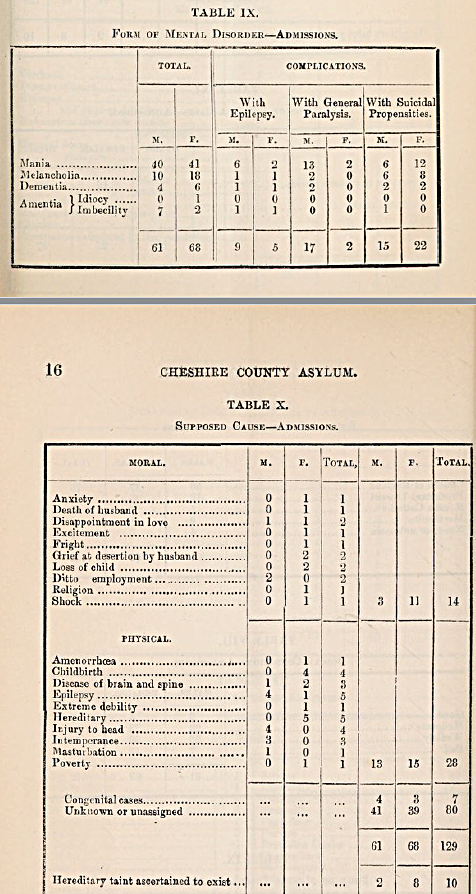

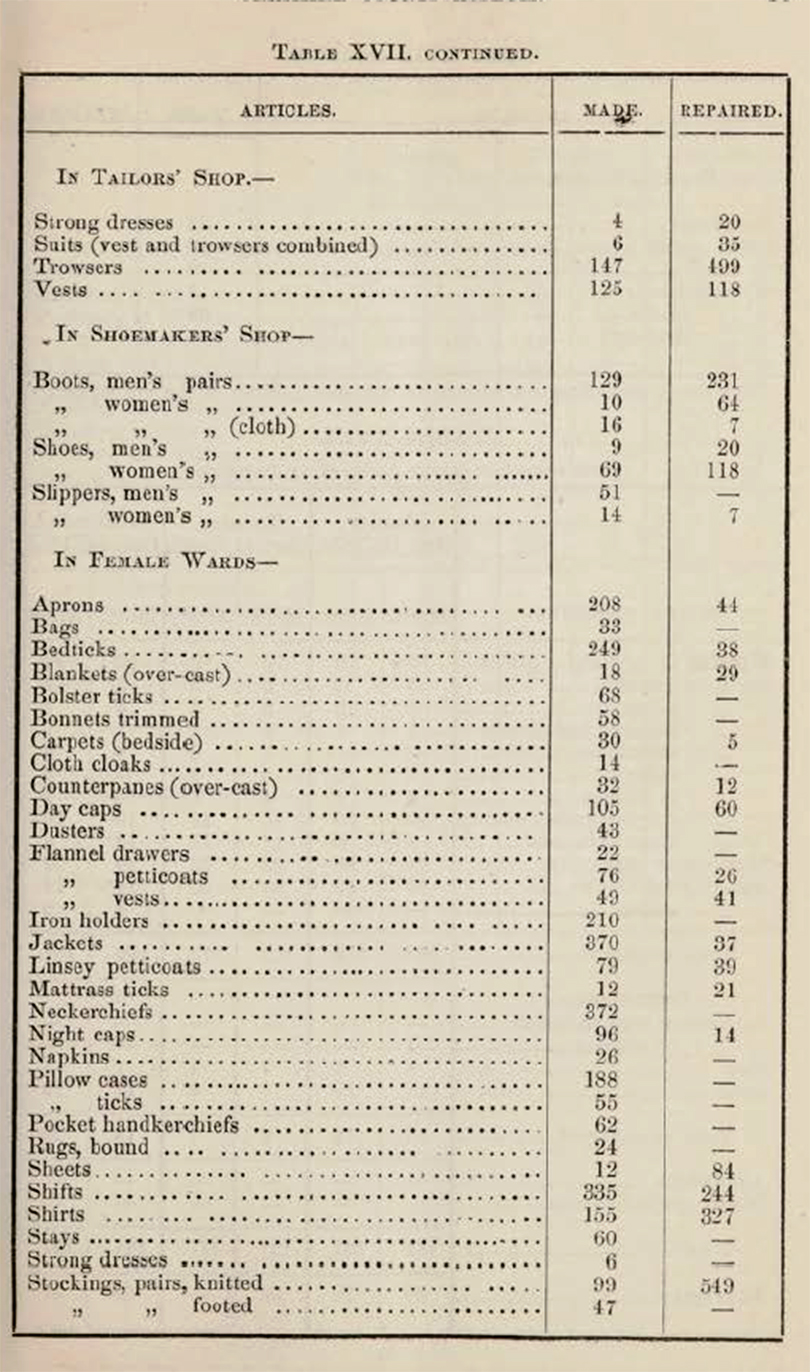

In every report the numbers of new admissions were listed both the symptoms with which patients were admitted in the tables accompanying the reports, together with the supposed causes in Table IX (until 1868). The supposed causes are of interest, because they are specific to individual cases, and change annually, although recurring causes inevitably appear from one year to the next. The following example is from the 1862 report about 1861:

The 1862 report for 1861 reported that the asylum was now capable of housing 500 patients, with the new extra capacity unused, resulting in the decision to charge private patients who were unable to afford more expensive solutions. It was deemed that the admission of this new class of patients required a set of additional rules that would be applicable to these new more privileged patients.

Occasionally something related to an individual patient is deemed important enough to report and these give some clues about the circumstances from which these patients came. For example, in the March of 1862 a “deaf and dumb idiot” was admitted from a workhouse, and within three days had developed symptoms of smallpox. A second patient soon showed the same symptoms and both had to be isolated from the rest of the asylum patients. Again in 1862 a female patient gave birth, and this child was “subsequently removed to the Workhouse.” In 1866 a woman died within six hours of having been admitted and the sad jury verdict determined that the death was due to natural causes “accelerated by ill-treatment, want of proper food and the miserable hovel she lived in.” In 1867 a female was admitted with advanced Phthisis Pulmonalis,(pulmonary tuberculosis, also referrred to at the time as “consumption”) in a state of extreme exhaustion. She gave birth a month later to premature baby, and both died. In the same year, a woman was taken to see her dying husband in her home near Middlewich, giving “no small degree a melancholy satisfaction to both, and probably was the means of saving the patient, a melancholic one, considerable subsequent distress of mind.” One of the female inmates gave birth to a child, which, when a month old, was removed by the Relieving Officer, and delivered to the husband. In another case of a childbirth within the asylum, both mother and child died. There are very few other examples listed.

There are plenty of references in the Cheshire Asylum reports to areas outside Cheshire that had asylums of their own, but would send some of their patients asylums outside their immediate areas, including Chester, when they became full to capacity, thereby incurring associated charges. An example from 1862 is the intake of patients from parishes in north Wales due to the Denbigh asylum being full. The charges imposed for taking in these patients was used to improve conditions at the Chester asylum, enabling the purchase of “a large portion of the furniture required for the new buildings, but for which the Committee would have been under the necessity of applying for a further sum to supplement the grant of £500 already made by the Court of Quarter Sessions for this purpose.”

It is discussed in part 2.1 (Ideology) how patients were put to work within the asylum partly to control costs, but more particularly to provide them with a sense of self and personal achievement. Women sewed and knitted, and sometimes helped out on the wards. By 1867 all the clothes, shoes and bedding were being made within the establishment. The report for 1868 shed more light on this. Of a total population (by the end of the year) of 255 men and 257 women, 120 men and 140 women were employed in productive activities in the asylum. 80-90 men worked in the garden and farm, 8 worked as tailors, 10 as shoemakers, 5 at other trades, and 55 in the wards and offices in unspecified roles. 100-110 women were engaged in sewing and knitting, 22 were in the laundry and washhouse, 9 were in the kitchen and offices and 30-40 assisted on the wards.

In 1870 it was recorded that “an excellent practice has lately been adopted” whereby every patient due to be discharged would be brought before the Committee so that they could be questioned about their treatment and asked if there were any complaints, following which they would have to sign a form confirming their statements.

The overall impression is one in which patients generally came from the lower levels of Chester’s social scale, with a few middle class patients, generally private, and that at the asylum they were integrated into a new community where they were cared for, and to which they could contribute.

xxx

Form of Mental Disorder

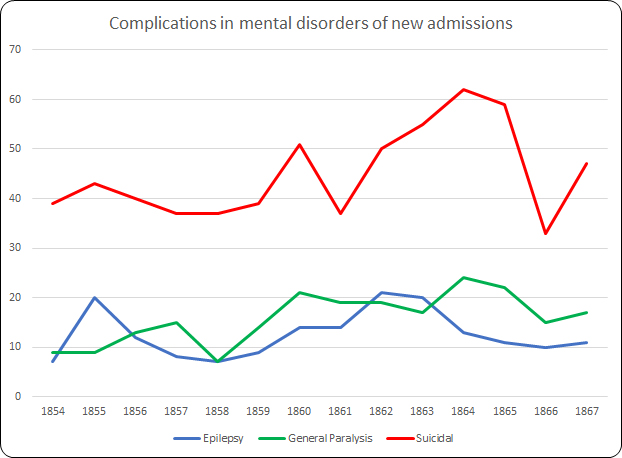

One of the tables in each report showed the main “disorder” with which patients were admitted, with any complications. They make for a fairly startling insight into just how varied and potentially difficult patient symptoms could be. It is difficult to find precise modern analogies for the forms of disorder shown, not only because they were not always precisely defined in the 19th century, but because definitions could differ from asylum to asylum.

The four main classes of disorder were Mania, Melancholia, Dementia and Amentia, the latter subdivided into Imbeciles and Idiots. I have listed Amentia as a single class in the above graph, due to the lack of any clarification on how idiocy and imbecility were distinguished by the asylum. Other causes could be added to the table as well. In 1855, for example, intemperance (alcoholism) was specifically noted as a direct and dominant cause of insanity in new admissions:

Intemperance, as usual, appears to have been one of the most fertile causes of the disease, and this was more especially the case amongst the class of skilled artizans who received high wages. As shewn in table 10, in fourteen instances the attack of insanity was directly attributable to it; and undoubtedly in a large number of the other cases, habits of intemperance acted as a predisposing cause. It unfortunately happens that the offspring of such parents are extremely liable to insanity.

However those shown above in Table IX from the 1855 report, were the main categories up until 1867 when the format of the tables changed, and the “forms of disorder” table was changed. Hill and Laugharne, looking at the Bodmin asylum data suggest that these conditions could be broadly understood as follows, although this is tentative, and reflects the difficulty that was found in categorizing mental illness in the 19th century. Mania is thought to have represented manic episodes, for which they suggest that a test would be to look at the age at which the symptoms began to manifest themselves, expecting to find it appearing in patients aged between 10-30 years old. Melancholia was more closely associated with what were later referred to as depression. They find dementia more difficult to pin down but suggest that it may equate to schizophrenia, but if correct, this too would have manifested itself in younger patients. Taber’s Medical Dictionary Online describes Amentia as “1. Congenital mental deficiency; mental retardation. 2. Mental disorder characterized by confusion, disorientation, and occasionally stupor,” but it was broadly associated with those who suffered from learning difficulties, described in the Chester asylum reports as “idiots” and “imbeciles.”

As well as the main forms of disorder, complications could have a considerable impact on any chance of recovery. Although suicidal tendencies accounted for a considerable proportion of each year’s intake, as shown in the chart above, the greatest complication for any possibility of recovery was General Paralysis, which was one of the most common cause of death in the asylum.

Suicide, which is discussed further below, could be guarded against within the asylum, meaning that even when high numbers of patients were admitted with suicidal propensities, there was a very low rate of suicide within the asylum itself.

General Paralysis of the Insane (GPI), to give it its full title, also known as General Paresis, impacted men far more often than women and was the most frequent contributor to the number of deaths recorded in the asylum each year, with much greater numbers usually found among men than women. As Kelley Swain illustrates, it was not understood in the 19th century, although not through want of speculation:

“Treponema pallidum” (in Swain 2018)

General paresis (or paralysis) of the insane (GPI) was crippling and terminal. It ended in loss of control over mind and body, often accompanied by grandiose delusions of wealth and power and, finally, paralytic death. There was no known cause. Could GPI be caused by overwork? Emotional labour? Mental strain? Sexual promiscuity? Drink? These were possible causes listed by William Julius Mickle in 1880. . . A disease of dissolution and disrepute, GPI was also considered a result of that most Edwardian horror: degeneration

In fact, GPI was the result of undiagnosed syphilis, a bacterial infection usually transmitted sexually, hence its association with disreputable activities. No cure was found until the early 1900s, when the bacterium Treponema pallidum was discovered in Germany, leading to the manufacture in 1908 of a drug called arsphenamine later renamed Salvarsan. GPI was a genuine problem for lunatic asylums like Chester’s. Because it was incurable, and it required constant nursing attention, patients who were admitted with GPI took up vacancies at the expense of those who might be cured. It was a massive dilemma.

The seizures associated with epilepsy were originally thought to be outbreaks of madness, and were treated accordingly but by the mid 19th-century there was a much better understanding, particularly as a result of the work by neurologist John Hughlings-Jackson, of the causes. In 1857 Sir Charles Locock successfully applied the first effective anti-seizure drug, potassium bromide, to epileptic patients. For much of the later 19th century epileptics began to be treated as a separate class of patient, either in dedicated wards and buildings or in epileptic colonies.

A recurring theme in the reports, which has been mentioned before, was the frustration that patients were not admitted until their conditions were very advanced, considerably reducing the likelihood of recovery and filling the asylum with those who could not be nursed back to health and cured at the expense of those in need.

It too often happens that to save expense, or else from misplaced charitable motives, the patient is detained at home by his friends, with a hope that improvement may take place; and when it is too late for medical treatment to be of any service, he is removed to the Asylum, where he is likely to remain for life, a burden to bis friends, or to the township to which he belongs; whereas, had be been sent as soon as the malady had manifested itself, there would have been every probability of his speedy recovery, and of his being able once more to support himself and family by his own labour.

John Hughlings-Jackson (1835-1911). Source: Wikipedia

In 1857 the report for 1856 reinforced the point, drawing attention to the fact that of the forty seven who had been discharged as recovered, thirty nine of those patients had been admitted within three months of having been declared insane.

The confusion of mental illness with neurological disorders in the 19th century was understandable, and it was only through the work of medical pioneers like John Hughlings-Jackson that the two began to be seen as separate fields of medical research, with psychiatry and neurology both developing into essential branches of medicine.

There is almost nothing in any of the Chester asylum reports about what sort of treatments were applied, so it is not possible to track how treatment might have evolved. Nor is there any information about how discharged patients were deemed to be “cured” or “relieved.” Nor is it explained why, if they were not in any way improved, they were discharged anyway.

xxx

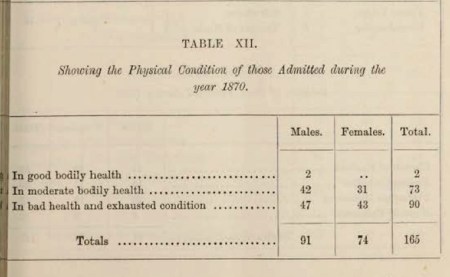

General health and disease

A recurring theme in the reports draws attention to the weak condition and general ill health of new admissions that undermined the efforts of the staff to support new patients. Many of those who died soon after admission were already in a poor state of health, in spite of being provided with good food and other stimuli. Those referred from workhouses were often in a very bad way. This was blamed in some reports on the Relieving Officer who was responsible, at parish level, for assessing paupers and their needs, and for delivering any suitable candidates to the asylums.

There was always the risk of a patient being admitted with a dangerous disease. In 1864 a patient suffering from smallpox was admitted, which lead to a new bye-law authorizing the Medical Superintendent to reject infectious patients. In 1865 this was acted upon when a potential patient was indeed refused admission. On the other hand, there is no mention in the 1867 report for 1866 about any patients contracting cholera, which was an epidemic in that year.

Patients transferred from the Workhouse

The Chester Workhouse, on the edge of the Roodee, hemmed in on all sides. Sometime after 1840. Source: ChesterWiki

The relationship between the Chester workhouse and the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum is an important one and needs far more exploration than is possible here. As Alistair Ritch has highlighted in his study of transfers between Birmingham are workhouses and asylums, there was a great deal of movement in both directions in England. Following changes introduced by the 1834 Poor Law Act workhouses were required to move certain patients to local asylums: “nothing in this Act contained shall authorise the detention in any workhouse of any dangerous lunatic, insane person, or idiot for any longer period than fourteen days” (section 45). They were often in very poor condition by the time the decision was made to transfer them, both before and after 1834, making it very difficult to treat patients both for ill health and for mental illness. In the other direction, those long-term residents of the asylum who were deemed to be both harmless and incurable might be moved to workhouses to make room for more acute cases.

In the 1857 report for 1856 the problem of workhouse admissions was highlighted, which provides a useful insight into the relationship between workhouse and asylum, and the problems in capacity that this represented for the asylums:

It appears that there are at this time more epileptic, idiotic, and chronic pauper patients in the different Workhouses of the County and elsewhere, than the patients actually

present in the Asylum; and as the Commissioners in Lunacy recommend that all these shall be brought into the public Asylum of a County, and also recommend that at least one acre of land for ten patients should be provided for their occupation, the quantity of land with that now proposed to be purchased would be in about that proportion, viz. 70 acres for 600 patients.

Dr Brushfield commented on the referrals from the workhouse in 1859, and how these were less likely to recover due to the lateness of the referrals, than those admitted early from other sources. This is a recurring theme, but was raised particularly with reference to workhouse transfers.

It cannot be too often reiterated, that the chances of the patient’s recovery depends in the great majority of cases upon the circumstance whether the removal to the Asylum is early or late after the primary outbreak of the attack. The patients admitted to the Asylum during the past year, were 11s a class, of a worse description than usual; for instance, at the monthly meeting in October, the following extract was read from my Diary:-

“I beg to call the attention of the committee to the bad and incurable type of cases that are now being brought to the Asylum. Of the eleven patients admitted since the last meeting, there is only one where there is much probability of a cure being established, there are two cases of doubtful issue, and the remaining eight are positively incurable. Seven of the eleven were admitted from workhouses, and four of this number had been the subjects of restraint.”

When a patient is sent to the Workhouse, which practice in some townships is the rule, considerable delay in the removal to the Asylum is too frequently experienced, and as a

When a patient is sent to the Workhouse, which practice in some townships is the rule, considerable delay in the removal to the Asylum is too frequently experienced, and as a

sequence, the recoveries amongst those brought from workhouses are proportionately few, and the deaths many. The following table of the cases admitted into this Asylum during the past year, will bear out the correctness of these remarks.

By 1860 concerns about overcrowding at the asylum, there being no more male capacity and only a few places available in the female wards, lead to a brief exploration of the various options, which included expanding the asylum yet again, shifting patients to other English asylums, and moving others to the workhouse. Of the latter option it was suggested that workhouses represented the least desirable option, “it being a fact well known to all experienced in the treatment of recent acute cases too often results in retarding the discovery, or in causing the degeneration from a curable into a chronic incurable state.” In the 1862 report for 1861 Dr Brushfield expanded upon this point:

In several instances where Patients, after having been quiet and harmless for many months, or even years, in the Asylum, have been removed to the Workhouse, they have, in the course of a short time, been sent back to the Asylum as “dangerous” either to themselves or to others, or to both.

In 1866 there were too few spaces for the number of patients referred to the asylum, and the only solutions were to transfer the new patients to other asylums, if any of those were lucky enough to have capacity, or to send them to workhouses. As none of the asylums approached had any spare capacity, it is assumed that several of the Chester asylum patients were sent to the workhouse in spite of Dr Brushfield’s considerable misgivings.

The subject of the relationship between the Chester asylum and the workhouse would reward a research project in its own right.

xxx

The emphasis on recovery

The objective of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum was not merely confinement but cure, although apart from a community and activity based approach to mental illness, it is by no means clear how recovery was to be achieved. The reports are concerned to record and discuss recoveries, as well as the reasons why some patients could not be cured. Some patients were too unwell to treat effectively when they were admitted to the asylum: “It is lamentable to find that in such a large proportion of the cases admitted, medical skill is of no avail.” There is a clear differentiation between those who have the potential for recovery and those who do not. In the 1855 report this was because of complications due to epilepsy and general paralysis, a recurring theme in these reports, and also because, in some cases, mental illness was too far advanced into the “chronic stage” for any improvement. The usual explanation for this is that admission came too late in their illness, as this example from the report, also for 1855, makes explicit:

It too often happens that to save expense, or else from misplaced charitable motives, the patient is detained at home by his friends, with a hope that improvement may take place; and when it is too late for medical treatment to be of any service, he is removed to the Asylum, where he is likely to remain for life, a burden to his friends, or to the township to which he belongs; whereas, had he be been sent as soon as the malady has manifested itself, there would have been every probability of his speedy recovery, and of his being able once more to support himself and family by his own labour. In table 13 it will be seen that out of the 52 cases discharged cured, 32 left the Asylum within six months from the time of their admission.

The report cites a case of one individual who was only kept alive by a stomach pump that administered food, and who died after five months.

This was reiterated in 1861 when Dr Brushfield wrote:

The proportion is wholly governed by the number of curable cases admitted, as of this

class 70 or even 80 per cent. are discharged recovered, hence the importance and necessity of sending the patients to an institution of this kind before the malady has assumed a chronic incurable form. In too many instances the Asylum, instead of serving the purpose of a hospital for curable cases, has simply become a receptacle for incurables.

In 1867 the 21st Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor was published, for the year 1866. It listed all the asylums with which it was concerned, showing the data for the total number of inmates in the asylum at year end, and the proportion of those deemed to be probably curable and those deemed to be incurable. Out of 481 patients (238 male, 243 female) only 13 were “probably curable” (5 males and 8 females) whilst 468 were “probably incurable. ” In the following year, 1868 the percentage of recoveries, 46.5%, was higher than in any previous years but no specific reasons are provided to account for the difference between these two sets of figures.

In spite of this gloomy prognosis, patients were fed well, if unimaginatively, three times a day, and for paupers, many of whom had probably had very little in the way of consistent and healthy diets, the provision of regular meals full of carbohydrates and protein was probably better than many of them had experienced, and was essential for any hope of recovery. The fact that the farm, on which many of the men worked, supplied a lot of the daily food supplies must have been a source of some satisfaction to male patients.

xxx

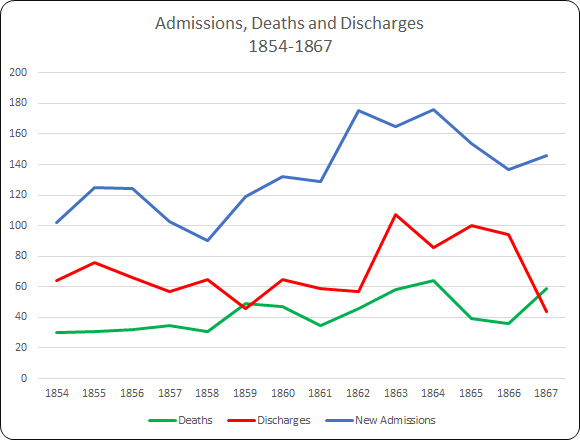

Discharges, deaths and escapes

xxx

Discharges partly reflected the success rate of the asylum, the overall aim of which was to return patients to society rather than retain them, so these were always displayed prominently in the tables and discussed in the text. A distinction was made between those who were considered to have completely recovered, those whose symptoms were relieved and those who had not improved. Superintendent Brushfield was well aware of how the statistical tables could disguise some of the underlying information about recoveries and in his 1860 report for 1859 attempted to clarify the situation as regards curable versus incurable patients:

Of course the proportion of recoveries must depend upon the proportion of curable cases admitted, which varies much from year to year: for instance, during 1858 the admissions consisted of 43 curable and 47 incurable cases, whilst in 1859 the numbers were much more disproportionate, there having been 49 of the former and 70 of the latter. Of the 49 of the curable class 26 were discharged as recovered during the course of the year, and nearly two thirds of the remaining 23 are progressing favourably towards mental restoration.

Causes of death shown in the 1857 report, including 12 cases of General Paralyis, 10 cases of Phthisis (which sometimes followed General Paralysis) and two suicides

Deaths were inevitable, and were the result of a variety of causes. In 1854 nineteen men and twenty women had been discharged, and there were a total of thirty deaths, a third of which were put down to “General Paralysis,” which was incurable and was the main cause of death over the entire period that these reports cover. In 1870 this figure still remained high (15 men and 7 women) In the 1860 report for 1859, Superintendent Brushfield highlighted the much higher than average number of deaths and some of its causes:

There was a considerable increase in the proportion of deaths and several circumstances contributed to swell the number. The mild winter of 1858, assisted in prolonging the lives of manv of our feeble cases for a few months, thereby lessening the mortality of one year to increase that of the next; whilst the severe weather that occurred during the middle of December last, operated very banefully on those suffering from great prostration of the mental powers, or organic bodily disease. The large number of aged persons admitted tended to produce a similar result. One-third of the number was due to general paralysis.

Tables from 1862 showing ages of patients who have died and the duration of their treatment before death

In 1855 and again in 1857 one third of admissions had been recorded as suicidal, but although suicide attempts were occasionally recorded, thirteen years had elapsed before two were successful in the same year, noted in the report for 1857. This is in spite of the fact that some patients had been admitted not only having suicidal tendencies but having made serious suicide attempts prior to admission. An example from 1857 describes how: “in several the attempts made were of the worst desperate description; and in two instances the patients at the time of their admission had extensive incised wounds of the throat which subsequently healed.”

Overview of suicides in the report for 1861

In 1861 two patients had been admitted who had attempted suicide by cutting their throats, one of whom had been confined within the workhouse for two years previously. The year’s only successful suicide lead to new measures to prevent a repeat:

For special notice is that of a male patient who committed suicide in the day time by strangulation. Every precaution appears to have been adopted with a view to guard against his known suicidal propensity. The open ironwork at the head of one of the old bedsteads, however, afforded him the opportunity he had sought. Nearly fifty of these bedsteads were in use when Mr Brushfield entered upon the duties of Superintendent in 1852. All since introduced have been of wood, and of a safe construction . . . It has, consequently, been deemed right to order an alteration, now in progress, in all the iron bedsteads, by the substitution of sheet iron for open work.

1870 was also a particularly bad year for those who were admitted having actually attempted to commit suicide, although there is no attempt to explain why this should be so, and no new suicide attempts were recorded after admission into the asylum:

Of the year’s admissions it was found that a large number had a strong suicidal propensity, and that several had made desperate efforts to commit self-destruction prior to their being brought here: the subjects of melancholia exhibited this proclivity in the greatest intensity. Six cases were received into the asylum with their throats more or less severely cut, all of whom however recovered of their wounds,. except one – a male patient – who died five days after admission, five days after admission, when a Coroner’s inquest was held upon the body, and the Jury gave a verdict to the effect that death was caused by self-inflicted injury. None but those connected with Asylums for the Insane can form an adequate conception of the anxiety which this class of patients causes to the Medical Officers.

Escapes were only noted in the tables where the person had been missing for over a day. There were several escapes in 1854, one in 1855, two in 1863, two in 1864 and one in 1870, which is a remarkably low number. One escape attempt resulted in the escaped man drowning in a local canal; this was considered to be an accident rather than a suicide attempt. This very good record was put down to the amount of freedom accorded to patients as well as their good treatment.

xxx

Re-admission

Re-admissions are not mentioned in every report but are interesting when they are, indicating that someone who had been discharged back into society had not been successfully reintegrated and needed to return to the asylum for treatment. It is unclear what sort of medical or emotional support someone discharge might or might nor receive from the asylum, although there was a charitable fund for helping them financially. A list in the 1863 report for 1862 displays re-admissions versus admissions since 1842. The percentages indicate that this was a fairly high annual number:

One of the problems with these figures is that the re-admissions do not correspond directly to the admissions, as some of them were admitted from previous years. Other reports make it clear that some re-admissions were within the year covered by the report, but that others clearly represented lapses after many years, so that the percentage of re-admissions does not relate directly to yearly admissions. The figures in this table are still interesting for two reasons. First, they indicate that re-admissions were generally quite low for the 17 years concerned, particularly as there does not seem to have been much in the way of after-care, but they did occur. Second, these figures had not been recorded in most of the preceding reports, although they must have been recorded somewhere for them to be included in the 1862 report.

xxx

Religion and education

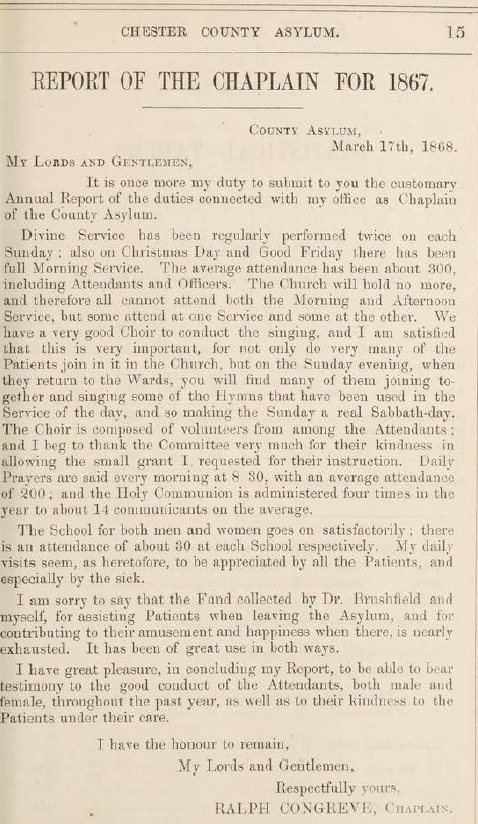

Access to Christian services was considered important not only for the moral and religious wellbeing of patients, but also to reduce the potential tedium of asylum life. The 1858 report for 1857 describes how a new residential chaplain was appointed:

The necessity of having Divine Service performed more frequently in the Chapel of the Asylum has recently brought under the attention of the Committee. After investigating the matter very fully, and finding that such services not only broke the monotony unavoidably connected with these Institutions, but exercised a more salutary influence on the patients, they appointed the present Chaplain, the Rev. R. Congreve, to be resident Chaplain, with a salary of £200 per annum, and an allowance of £50 per annum for a house, until the same could be provided for him. Divine Service will now be performed once every week day and twice on Sunday, instead of (as heretofore) once in the week and once on Sunday, and the Chaplain’s whole time devoted to the Asylum.

From 1858 the annual report occasionally included a section contributed by the Reverend Congreve, and it is one one of the aspects of asylum life on which the visiting commissioners of lunacy regularly commented in the annual report. There were two services on Sundays, one on Fridays, and prayer readings every day in the Recreation Hall, as well as services on Christmas Day and on Good Friday. A choir was made up of both attendants and patients, and Reverend Congreve reported that “all the Sunday evening when they return to the wards, you will find many of them joining together and singing some of the hymns.” Holy Communion was also organized four times a year for a small minority of the asylum residents who required it (for example, in 1867 there were 14 who took advantage of this provision, out of a total number of 526 patients at year end).

From 1858 the annual report occasionally included a section contributed by the Reverend Congreve, and it is one one of the aspects of asylum life on which the visiting commissioners of lunacy regularly commented in the annual report. There were two services on Sundays, one on Fridays, and prayer readings every day in the Recreation Hall, as well as services on Christmas Day and on Good Friday. A choir was made up of both attendants and patients, and Reverend Congreve reported that “all the Sunday evening when they return to the wards, you will find many of them joining together and singing some of the hymns.” Holy Communion was also organized four times a year for a small minority of the asylum residents who required it (for example, in 1867 there were 14 who took advantage of this provision, out of a total number of 526 patients at year end).

In the report for 1863 it was noted that church attendances averaged from between 108 to 118. In 1867 the church had reached its capacity of 300, made up of both patients and attendants, and many had to be excluded. As a result, in 1868 the pews were reorganized to allow an additional 70 to attend. During the closure for this alteration, “as many patients as could be trusted” were accompanied to Upton Church. The average congregation after the reorganization was now 320, still including both residents and attendants.

Reverend Congreve managed a charitable subscription fund called the Convalescent Fund, which was contributed to by people from the local community to assist those who were discharged, which was designed to help them to re-establish themselves. There were occasionally concerns about this running very short of funds, but every now and again it received a generous contribution or legacy. The report for 1867 describes how a a legacy of £100.00 was provided, making a substantial difference to the fund.

The chaplain also managed two voluntary schools, one each for male and female, as a form of leisure activity. A schoolmaster was provided by the men, but women were taught by two nurses. Over time as well as Bible study and reading, the school taught writing and basic arithmetic and one of the chaplain’s activities was to deliver books and periodicals to the patients, taking particular effort to make sure that those who had difficulty reading had material with plenty of illustrations. In 1867 the school attracted 30 men and 30 women.

xxx

Personnel

Staffing consisted of a Superintendent, an Assistant Medical Assistant, a Matron, a number of male and female attendants and nursing staff. These were supplemented by a bailiff, a head gardener and his staff, workshop artisans, the lodge keeper and his wife, and a porter. The farm, which included both livestock and crop production, would presumably have been staffed quite extensively.

Staffing consisted of a Superintendent, an Assistant Medical Assistant, a Matron, a number of male and female attendants and nursing staff. These were supplemented by a bailiff, a head gardener and his staff, workshop artisans, the lodge keeper and his wife, and a porter. The farm, which included both livestock and crop production, would presumably have been staffed quite extensively.

Within the asylum, efforts were made to ensure that women staff worked in the female wards and that male staff worked in the men’s wards. Long-term employees were provided with pensions. In 1854, for example, a resident steward was appointed, a new matron replaced the incumbent matron who was provided with pension after 15 years of employment, the head attendant retired due to ill health after over 20 years of employment. Both were provided with a pension of £20.00 per annum. The outgoing Medical Superintendent was granted a pension of 200.00 per annum.

Staffing levels are usually reported on within the report, and in 1861 there is a useful insight into staffing at the asylum at that time:

On the male side there are a, head attendant, 13 ordinary attendants, (there being at present one vacancy,) and a gardener and an engineer, each of whom has charge of patients during the day. On the female side, under the Matron there are 15 nurses employed exclusively as such, and a laundress, a cook, and a housemaid. The above are exclusive of the night attendants, one in each division, whose duties, during one night in about 13, are taken in turn by the ordinary attendants.

There had been a reference in the report for 1866 to note that “in most cases” attendants had maintained good standards, which looked somewhat as though some details were being glossed over. In 1867, it was not deemed possible to ignore that “on one or two occasions” attendants had been charged with striking patients, although no-one was dismissed. From this year there were repeated problems in this regard. The report for 1867 also commented that female attendants were short by two due to the difficulty of hiring suitable personnel. It was suggested that this might be due to the low starting salaries, and it was recommended that this might be increased.

The Handbook for Attendants of the Insane. Source: Royal College of Nursing, “Out of the Asylum”

In 1865 the problem of training frontline staff, both attendants and nurses, in lunatic asylums was recognized by the medical profession and a manual was produced for their use, the Handbook for Attendants on the Insane. It was known colloquially as “The Red Book.” The book cover on the left shows that this was the sixth edition, a measure of its success. You can read a copy of it on the Wellcome Collection website here (the 1884 edition). It was not until the early 1890s that training schemes and examinations were first set up for frontline staff at lunatic asylums by the Medico-Psychological Association (which later became the Royal College of Psychiatrists).

In 1868 “considerable difficulty” was experienced finding “efficient and well-conducted” attendants to fill vacancies. The loss of the Head Female Attendant in that year due to ill health lead to the combination of her role with that of the Matron (it is not recorded quite what the matron made of this). These staffing difficulties may contributed to the finding of the Lunacy Commission Visitors in that year that although men presented an acceptable appearance, some of the female patients to be “poorly clad and still more untidy, and as if ill-attended to.” One woman complained of injuries imposed by the staff, still visible, that had not been escalated to the upper hierarchy for investigation. Although her bouts of violent epilepsy meant that her injuries may have been accidental or the result of trying to pacify her, the failure to report the incident was a cause of concern. However, it is clear that there were real problems with some of the staff. In the same year, 1868, a few of the staff members were dismissed for “misconduct, wilful neglect of patients and incompetency” and the rules for staff were revised to ensure the regulation of conduct within the asylum and to ensure proper attention to patient care, but there were still occasional problems.

In spite of genuine efforts, in 1869 several male attendants were dismissed, one of whom was prosecuted for striking a patient and was fined £10.00 per costs, which he paid rather than being imprisoned for three months (to put this in perspective, the National Archives Currency Converter suggests that today this would be equivalent to around £626.00, or 50 days salary for a skilled tradesman).

The combination of low salaries and increasing numbers of patients apparently made it difficult to hire sufficient attendants who had both the skills and the physical and appropriate personal attributes to care for patients according to the values of the moral treatment approach. The experience at most asylums was that as patient numbers grew, it became increasingly difficult to maintain this empathetic approach, and it would be interesting to know how Dr Brushfield fared after he moved to Brookwood, which at the time of his new appointment had capacity for 650 patients.

Asylum Deaths in Overleigh Cemetery

Family gravestone that includes the name of Ellen McLean Thurston, who died in the asylum at the age of 42. Photograph by Christine Kemp. Source: FindAGrave.com

Without access to the asylum’s records it is difficult to find out information about patients, why they were there and how they died. I have not yet found out where Asylum patients were buried prior to the opening of Overleigh Cemetery in 1850. However, a burial dataset from Overleight itself can, in some casesbe matched up to newspaper reports. The contents of this section have been provided by Christine Kemp’s entries for in the Virtual Asylum Cemetery for Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries on the Find A Grave website, putting names to some of the anonymous statistics captured in the annual report.

Overleigh Cemetery opened in November 1850. To date Christine Kemp (Friends of Overleigh Cemetery) has found records of 67 patients at the asylum having been buried at Overleigh between 1852 and 1900, as well as 3 from other asylums (Tranmere, St Mary’s Parish and Latchford). The youngest if these was 15 and the eldest 77. Two were suicides. According to Chris’s research on the Asylum Virtual Cemetery, of the 67 known Asylum patient burials, 26 (39%) had no memorials and are in unmarked graves, some of them were buried in common graves (7, or 10.5%), and one of them was interred in a communal cholera grave. In five cases, patient burials are recorded on plots with memorials, but their names are not mentioned on those memorials. Given the size of the asylum and the numbers of deaths recorded in the annual reports, others must remain to be identified or were buried elsewhere. Cremation was not a possibility in Chester until as late as 1965.

Causes of death are almost never shown on gravestones, but some of them refer to the suffering of the deceased in life. The memorial for asylum patient Edward Edwards, who died at the age of 69 on the 26th January 1894, is an example of this genre and reads: “His Languishing Head is at Rest / Its thinking and aching are over / His quiet immovable breast / Is heaved by affliction no more.”

The understated gravestone of Edward (Ned) Langtry, husband of actress Lily Langtry. Photograph by Christine Kemp. Source: FindAGrave.com

Chris has managed to track how some of these people were employed in life, and most of those that she had were in fairly modest work, as one would expect from an asylum set up to assist paupers and those whose families could not afford their care. This agrees with the asylum records which show how patients were employed prior to being admitted. A number were labourers, as well as the wives of labourers. Others are identified as a grocer’s assistant, a tailor, a porter, the wife of a wagoner, a pub landlord and the wife of a pub landlord, a sergeant major, a stone mason, a bricklayer, a mariner, the wife of a coachman, a “gentleman’s gardener,” a painter, a butcher, a fitter, a store and timekeeper, a char-woman, an engine driver, and a collier.

An unusual asylum patient was Edward (Ned) Langtry, the former husband of popular actress Lily Langtry, from whom he had separated in 1887. In October 1897 he was found wandering after a bad fall in a state of delirium and was referred to the asylum by a magistrate, although he would probably have been better referred to hospital care. He died in the asylum after nine days, suffering from “inflammation of the brain.” His gravestone is a very understated affair, but the newspaper records that Lily Langtry sent a very impressive bouquet! The full report of Ned Langtry’s death was reported in the Chester Courant, which can be seen on Chris’s entry on the FindAGrave website.

The asylum deaths reported in newspapers are useful exceptions, because most of the asylum deaths were not usually reported in any detail in the newspapers, such as the Cheshire Observer and the Chester Courant, unless the story was in some way sensational. For example, another newspaper story reports on the death of asylum inmate Martha Miller who was buried in Overleigh Old Cemetery in an unmarked grave in 1879, and whose acts against her children makes for grizzly reading:

Grave of Martha Miller. Photograph by Chris Kemp (who marks the position of unmarked plots using bunches of flowers). Source: FindAGrave.com

She was the 3rd wife of Daniel Miller, Innkeeper of the Yacht Inn, Watergate Street, Chester. He had four living children from his previous marriages and two children with Martha, who was expecting their third. Martha had been in delicate health and had ruptured four blood vessels in the last nine months and had become quite despondent. On a Friday night in June she went to bed with two of her children from her present marriage, Alice aged 2½ yrs and Elizabeth Mary (Lizzie), aged 12 months. Shortly afterwards screams were heard by her stepdaughter Emma. Daniel broke down the bedroom door because it was locked, to find Martha had cut the throats of the children with a table knife, one fatally. She then had tried to commit suicide by the same means. Doctors were called for, who assisted with staunching the flow of blood. Martha who had become violent was put in a straitjacket and confined to the County lunatic asylum, Upton, Chester. Lizzie was taken to the infirmary where she recovered. Martha died at the lunatic asylum aged 30 yrs, after giving birth prematurely. At the Coroner’s inquest she was found ‘guilty of wilful murder’ of Alice Miller. Martha was buried on the 16th October 1879. Her baby daughter Martha, who was born prematurely in the asylum died just a few weeks after her mother on the 30th November 1879. (Source:- Cheshire Observer 21st June 1879 and Chester Courant 15th October 1879) [Researched by Christine Kemp and recorded on the FindAGrave website]

Another example is shoemaker Joseph Crawford whose death was reported in the Cheshire Observer on 14th November 1896. He had been in the asylum for eight years, suffering from “chronic mania” and died suddenly, returning from church. Interestingly, although the gravestone gives the name of his wife, who had died in 1882, and there was plenty of room for his name, and Chris has found a record of him being buried in this plot, his name is not mentioned on the gravestone. Either there were no funds to inscribe the stone, or the manner of his death had lead any remaining family to decide to exclude his memory.

It will be very interesting to try to match the cemetery data with the asylum’s own records when the latter become available in 2026. Although the Cheshire Archives and Local Studies listing of what they hold indicates that there are no burial records for the asylum, they do hold records of deaths, so it may be possible to extract information from the latter to tie in to the cemetery data.

I have assembled all the information that Chris has made available on her Virtual Asylum Cemetery in a 6-page table, which can be downloaded here, with accompanying notes.

xxx

Sample page from the table and notes showing Cheshire Lunatic Asylum deaths buried at Overleigh Cemetery, assembled from data gathered by Christine Kemp.

After 1870

The asylum continued to grow after 1870, and was still operating when it was absorbed into the NHS in 1948. On 31st December 1870 there were 536 patients in the asylum. In 1910 this had risen to 1000, 1500 in the 1920s and 2000 in the 1930s. In 1895 a completely new hospital was added to the site to the north of the original 1829 building, designed by Grayson and Ould, freeing up the 1829 building to be used as the women’s ward. In 1912 a new dedicated block was built for epileptics, which had a more domestic feel to it.

The former Parkside Lunatic Asylum in Macclesfield, which opened in 1871 as a second Cheshire county asylum, to ease some of the pressure on Chester. Photograph by Colin Park CC BY-SA 2.0. Source: Wikipedia

In the 1860s it became clear that the hospital, catering for the entire county, was simply unable to cope, and the decision was made to build a new asylum to serve the east of the county. The Second Cheshire Lunatic Asylum, also known as the Parkside Lunatic Asylum opened in May 1871 to accommodate 700 patients, with additional buildings added later to absorb over 1500 patients by 1938. The Parkside Lunatic Asylum’s architectural style and layout represent a completely different paradigm from that of the original Cheshire Lunatic Asylum building of 1829. It was designed by Robert Griffiths, who specialized in institutional architecture and was built of red brick with features picked out attractively in contrasting pale and black stone and dressings. The design is in the Italianate style, looking rather like a downscaled version of Osborne House (built for Queen Victoria on the Isle of Wight between 1845 and 1851). Instead of a single building linked by a main corridor, Parkside was built on the pavilion-corridor arrangement, with discrete blocks connected by multiple corridors.

Future research potential

The reports used here, the annual Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendents, have so many statistical tables that have only been touched on here, and I have simply presented what they contain. There has been no attempt at analysis. A well-structured project to analyze this data would reveal much more than I have been able to even hint at for the asylum in the mid-1800s. In addition, I have not discussed the accounts that are presented in the same reports, and that would benefit from the attention of someone who is familiar with accounting methods.

Cheshire Archives and Local Studies contents listing of records available when the offices open in 2026

There are many untold stories that live outside the reports used here, from the chairmen, the committee members, the visiting committee members, the staff, patients and those local community residents who paid into the voluntary fund for discharged patients. It will be fascinating to see what is available in the Cheshire Archives and Local Studies office in Chester when it reopens in 2026 so that the earlier and later history of the asylum can be investigated, and it may be possible obtain insights into some of the individual stories of those who worked at, were admitted to and who contributed to the asylum.

It will also be very interesting to try to match Cheshire Archives records with the the Overleigh cemetery and inquest data. Although the Cheshire Archives listing of what they hold indicates that there are no burial records for the asylum, they do hold records of deaths, so it may be possible to extract information to tie the two datasets together. For example, it should be possible to match admission and discharge names with those in Overleigh and track back to inquests and newspaper reports.

At the same time, it would be worth investigating the Riverside Museum in Chester, which also has archives that are relevant to the asylum, and although these have not been digitized a listing of its holdings can be downloaded here. Objects at the same museum may also provide insights into the material culture of the asylum at different times.

Another aspect of the Riverside Museum is that it informs visitors about how nursing became professionalized. Although this might seem like history from above, as nursing was part of the infrastructure of control, in fact nursing was itself in its very earliest stages. The role of women in the operation of an asylum is an aspect of how asylums developed. Each asylum had a matron, and there was one from the beginning at the Chester asylum, but quite what her role was in the asylum, and how many female staff she oversaw is not entirely clear. Female staff would have been needed for female patients. How much of this was caring and how much enforcement would depend on the nature of the patient and her symptoms. At what point female attendants became a professional female body of nurses, becoming more expert and informed throughout the 19th century, is unclear, but the professionalization of nursing provided women with the opportunity to take on roles that were not merely menial, although such roles of course existed, but could be increasingly skilled. If the data is available, and it is a big if, research into the role of women in the Chester asylum might produce some very interesting results when combined with other data and compared with nursing in hospital infirmaries and orphanages.

I originally intended to do a search on the asylum via the British Newspaper Archive, but the reports were so rich that I ran out of both room on this post, and time, so I decided to leave that for now, and perhaps pick it up at another time. The same can be said for the Reports of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor.

The abandoned Denbigh Lunatic Asylum. Photograph by Steve R. Bishop. Source Everywhere from Where You are Not

Other institutions also related directly to the Chester asylum. Several asylums had a relationship with the Chester asylum, each exchanging patients when they reached capacity, and this would be worth investigating. One of those asylums, the Denbigh asylum, would be worth an investigation in its own right, as would the Macclesfield Parkside Asylum that opened in 1871 in east Cheshire.

The role of the clergy in the Chester asylum is interesting, and the role of clergy in other asylums would also be well worth exploring for comparative purposes. Perhaps most importantly, the relationship between lunatic asylums and workhouses was obviously of fundamental importance to both types of institution, with problems associated with how patients were transferred between them, and this would be a fascinating area of investigation.

Finally, It would also be really useful to tie in the history of Victorian Chester with that of the asylum and see if there is any way of tying the two together to find correlations.

Final Comments on the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum

The Cheshire Lunatic Asylum was built in an era of social reform, and evolved during a period when philanthropy and social conscience were translated, painfully slowly, into governmental intervention and the passing of new laws. The 1829 Building represents one of many strategies to cope with the multiple challenges of all the symptoms of mental illnesses, which do not have, after all, a single identifiable cause.

One of the buildings once associated with the lunatic asylum, possibly the “villa” built for the treatment of epileptics in 1912. Never a thing of architectural beauty, it’s still a part of the asylum’s heritage, and very sad sight in this condition. As of April 2025 it is a hive of activity, and is perhaps being converted for new use

As the 19th century developed beyond 1870, asylums continued to grow and new custom-designed institutions could be absolutely vast. It is clear that the buildings of the Chester Lunatic Asylum continued to grow and adapt to meet demand. In the first years of the 1890s the decision was made to add a completely new building, which was built between 1892 and 1898 to the north of the original building. This housed the male patients, whilst the original building was used for women. In 1911 a separate building known as “the villa” was established near the chapel for epileptics, and other buildings were established after the First World War. The site continued to be expanded in the late 19th and throughout much of the 20th century to meet growing demands for its services. It is by no means clear, without access to the reports, what sort of ethos and approach was taken when the asylum’s population had become so big.

The new NHS took over the hospital in 1948 and in the 1970s it became a department of the new general hospital that combined the Chester Royal Infirmary and the City Hospital. In 1984 it was renamed the Countess of Chester. In 2005 its original function was replaced by the Bowmere Psychiatric Unit and in 2016 Ancora House (the latter for young people, shown at the end, a presumably deliberate modern echo of the 1829 Building).

The 2016 Ancora House, just behind the chapel, employs some of the same devices that were used in The 1829 Building, with a central, noticeable and colourful entrance flanked by evenly positioned rectangular windows on a long facade. Even the sculpture outside is a throwback to attempts to make the surrounding estate more attractive.

The 1829 Building is no longer longer devoted exclusively to mental health care but contains other departments too. Other parts of the Countess of Chester continue to offer psychiatric support as mental illness continues to be a problem for families, for state and for society. The modern Ancora House which opened behind the 19th century asylum chapel in 2016 and is shown here has now taken over much of that role.

Chester asylum was an early adopter of many aspects of the “moral treatment approach,” particularly impressive in a public asylum. With access to the airing courts, gardens, and facilities for entertainment and social engagement, the Its oversight committee and its superintendents seem to have had the interests of its patients at heart, even when the growing numbers of patients was clearly becoming a problem as the century proceeded. I have not yet been able to follow its fortunes beyond 1870, and I do wonder if, like so many contemporaries, it became swamped with the sheer volume of patients, and began to abandon its attempts to create an empathetic and socializing environment. That’s a project for another time.

There are several other lines of potential investigation, with many more avenues to pursue, covering a much longer timespan than the sixteen years of 1854-1870 covered here, and there is a lot of work to be done on this very important topic to understand mental healthcare in the 19th century and more recent periods in the Cheshire and neighbouring areas. It would be lovely to see something like the Staffordshire’s Asylums Project set up for Chester.

Final Comments on parts 1 and 2

It has been an absolute voyage of discovery to learn about the development of lunatic asylums in England and Wales, and often thoroughly hair-raising. The notoriously punitive asylums of the late 17th and early 18th century became more regulated, and reformist asylum owners introduced new “moral treatment” approaches that were far more empathetic, attempting to work towards cures. Many of these approaches were incorporated into public asylums, and as early as 1853 the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum had abandoned the use of physical restraints, in accordance with new rules. These approaches acknowledged that there was no cure-all solution, and that different symptoms required flexibility towards the provision of a range of treatments.

It still seems remarkable to me that as I was reading all the standard texts, as well as first-hand 19th century accounts about lunatic asylums, both public and private, the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum is almost never mentioned under any of its alternative names. The first thing I do when I get hold of a new book is flip to the index, or if it is a paper saved as a PDF, do a word search, but Chester is almost never mentioned. It seems to have fallen between the cracks in the history of 19th century lunatic asylums, which strikes me as somewhat peculiar. As a vast county lunatic asylum for paupers, growing every year, and battling to maintain standards with ambitions to restore its patients to society, it seems to have been something of a pioneer. And yet it is almost never mentioned.

Page 487 from Conolly’s 1830 “An inquiry concerning the indications of insanity : with suggestions of the

better protection and care of the insane”

Reading the original texts of people like Samuel Tuke (1811), John Conolly (specifically his 1830 thoughts) and Robert Gardiner Hill (1838) and even the later reports for the Chester asylum, there is a sense of a brave new world, an innovation of care for the mentally unwell, and a profound interest in helping those who were suffering to find a route back to a conventional and peaceful life. The Cheshire Lunatic Asylum under Dr Nadauld Brushfield was a part of that trend to find answers and help rather than subjugate the mentally ill.

With hindsight, the approaches that seemed so pioneering, the product of real humanity and social conscience, were limited in what they could achieve and they have come under some criticism today. First, it is suggested that they suffered from a normalizing attitude, failing to differentiate for treatment purposes between multiple possible causes of insanity, whether medical or psychological, treating all forms of mental illness as though they would respond to a single homogeneous approach. These ethically driven asylums have also been accused by influential writers like Foucault of trying to use coercion and incarceration to impose strict behavioural norms as a form of social control to conform to middle class values of decorum and self-control, although this seems to miss the point that patients in many asylums were no longer treated as sub-human but were given the dignity of being treated as coherent, thinking participants in a community and were provided with an opportunity to learn how to re-integrate. However not all mental afflictions could be approached with those treatments. As more people entered asylums a significant problem seems to have been one of resources. The empathetic approach of moral treatment became far more difficult to apply to even those for whom it may well have worked. At the same time, there was a change of direction to begin categorizing different types of mental illness to make the task of looking for solutions, remedies and cures far more scientific. It resulted in some truly shocking approaches, most of which have now been abandoned.

There is a sense running through the 16 years of the reports used here that the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum, whilst experiencing problems due to overcrowding and occasional personnel issues, was a well-run and compassionate institution that suffered few suicide or escape attempts, and did its best to provide quality of life for its inmates. Even so, care did not equate to cure and it is obvious that there was a long way to go before treatment was converted to remedies and solutions that endured.

Finally, the uncertainties regarding mental health today mean that the 19th century attempts to address these issues are all the more impressive, even when the challenges of implementation did not live up to what were often, although not always, very good intentions. As I commented at the end of part 1, and since which time I have done a lot more reading on the subsequent 20th and 21st history of mental health, from the beginning of lunatic asylums governments have struggled to know how to cope with those suffering from mental illness. Institutional care for patients suffering from mental illness is no longer a prominent feature of state responsibility, specialist institutions having been largely replaced by “care in the community” since the late 1980s when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, responding to an Audit Commission report in 1986, made it a reality. This potentially deprives the mentally ill from a sense of community and support that institutions dedicated to their care might provide. Some social scientists and sociologists like Andrew Scull argue that apart from a very few exceptions like syphilis and pellagra, absolutely no consensus exists even today on what causes mental illnesses or how to handle most forms of severe mental instability: “A penicillin for disorders of the mind or brain remains a chimera.” Whilst medicine continues to make advances all the time, and in spite of the fact that “mental health” is now one of the most over-used terms in modern society, the treatment of mental illness is still in need of much more investment and resources.

Finally, the uncertainties regarding mental health today mean that the 19th century attempts to address these issues are all the more impressive, even when the challenges of implementation did not live up to what were often, although not always, very good intentions. As I commented at the end of part 1, and since which time I have done a lot more reading on the subsequent 20th and 21st history of mental health, from the beginning of lunatic asylums governments have struggled to know how to cope with those suffering from mental illness. Institutional care for patients suffering from mental illness is no longer a prominent feature of state responsibility, specialist institutions having been largely replaced by “care in the community” since the late 1980s when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, responding to an Audit Commission report in 1986, made it a reality. This potentially deprives the mentally ill from a sense of community and support that institutions dedicated to their care might provide. Some social scientists and sociologists like Andrew Scull argue that apart from a very few exceptions like syphilis and pellagra, absolutely no consensus exists even today on what causes mental illnesses or how to handle most forms of severe mental instability: “A penicillin for disorders of the mind or brain remains a chimera.” Whilst medicine continues to make advances all the time, and in spite of the fact that “mental health” is now one of the most over-used terms in modern society, the treatment of mental illness is still in need of much more investment and resources.

Afterthought – coats of arms associated with the asylum

This is the emblem included on most of the Reports of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendent of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum, and a version of it appears on the pediment of the 1829 building. Both versions show the Chester coat of arms at the centre, showing the usual three wheat sheaves, but the mottos differ.

In the report version, the crowned coat of arms has the words “Honi Soit qui mal i pense” around the three sheafs, meaning “shame on anyone who thinks evil of it.” The text on which the arms rest reads “Antiqui Colant Antiquum Dierum” meaning “Let The Ancients Worship the Ancient Days.”

On the pediment there is no text around the coat of arms, but beneath the motto on the pediment the text reads “Jure et dignitate gladii, a phrase often associated with the Chester coat of arms, meaning “by the right and dignity of the sword.” Sorry it’s a bit fuzzy – I took it with my smartphone when I was there for a jab!

Flanking the coat of arms in both examples are two dragons, each with wings and forked tails. The dragons in the pediment only have two legs. In both versions each dragon holds a feather, the meaning of which eludes me, although I believe that this motif is usually associated with the Black Prince (Edward of Woodstock, son of Edward III, who had been invested with the earldom and county of Cheshire in 1333), and was later adopted by Henry VII. If anyone can decipher this dragon-related symbolism for me, please get in touch!

xxx

Sources:

This second part of the piece on the Cheshire Archaeological Asylum depends almost completely on the annual Reports of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendent of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum Reports for the years 1854-1870. Thankfully, the Wellcome Collection website has the digitized records of the Reports produced between and 1855 and 1871 (relating to the years 1854 to 1870), which have been digitized and are available for download free of charge.

All other sources are listed on a separate page because of its length, covering both parts of the post, updated at the time of posting part 2 here:

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/heritage/sources-for-cheshire-lunatic-asylum/

==