xxx

For those with unwilling legs please note that in [squared brackets, and highlighted in bold], are alternative routes that avoid steps and any other observed challenges. On the above maps the dotted line in green, is the only way of getting on to the Queen’s Park footbridge avoiding steps.

As well as the numbered sites, turquoise stars show other sites nearby that may be of interest. Each of the numbered and starred features deserves a post in its own right rather than the short burst of text allowed for each, but hopefully there is enough to make the walk informative as well as enjoyable, and in some cases I have hyperlinked to sites with more useful details.

You can download the text of the walk, including the maps, as a PDF here (but without the introduction, the list of sources and without ink-hogging images).

xxx

Introduction

Together with the city walls, this is my favourite walk in Chester, incorporating some lovely riverside footpaths and green spaces beginning at the Little Roodee car park on Castle Drive. The entire walk is on metalled surfaces, and is therefore very suitable for all seasons. It starts with the Grosvenor Bridge, turning in to Overleigh Victorian Cemetery and taking it from there along the River Walk.

There is plenty to enjoy along the south bank of the Dee, with lovely and peaceful riverside walks separating points of interest such as Minerva’s shrine, Handbridge with the Old Dee Bridge and Weir, and the Queen’s Park footbridge. The Groves is the northern counterpart to the River Walk, with its Victorian grandstand and array of cafes, ice cream parlours and the southern stretches of the Roman-Medieval walls. Back past the Old Dee Bridge, the walk takes in the former old Dee mills, the Gothic Revival hydroelectric station, the remains of the former prison’s outer wall, the Wheeler Building that houses the Riverside Museum and the Royal Infirmary stained glass, and then returns along the river bank to the Little Roodee.

The walk takes in several periods of Chester’s architectural history, from the Roman, through medieval periods, skipping the early Stuart and Civil War years. The Bear and Billet public house on Lower Bridge Street represents the later 17th century, but most of the remaining architectural history on the walk resumes with the Georgian architecture of the 18th century, plunging headlong into ambitious Victorian expansion and alteration. From a distance, seen from the Grosvenor Bridge, is the Art Deco water tower, which is a nice addition to the mix. Two examples of the less fortunate periods of 1960s and 70s architecture that afflict Chester like a bad rash also appear, but although one of them is particularly bad (the “Salmon Leap” apartments on the Handbridge side of the Old Dee Bridge) the other is somewhat less objectionable (the ex-Cheshire County County building, now the University of Chester’s Wheeler Building). A very modern building, nicely done on a budget, is the cafe in the Little Roodee car park with its environmentally friendly “green” roof.

The Walk

1) Roodee carpark, toilets and café

The walk starts from the Little Roodee car park on Castle Drive, which lies along the northern edge of the River Dee. There are plenty of other places in Chester to park, and there is also the very reliable Park and Ride, but this is a useful place to start the walk, including a very nice café with excellent coffee and good snacks, with public toilets within the café (there are other public toilets on The Groves, opposite the bandstand, shown below). The bottom of the car park provides a good viewing point for no.2, the Grosvenor Bridge.

For those wanting to explore the river walk to the east, circling the edge of the Roodee and over to the west of Chester, this is also an excellent starting point.

The postcode for the carpark is CH1 1SL or the exact location for the entrance to the car park is What3Words ///swung.statue.limp), which can be used in most SatNavs. If you are coming in by Park and Ride, ask the driver tell you when the stop is approaching for Adobe (big black glass building) on the Grosvenor Road. The return bus stop is opposite Adobe on the castle side of the road.

2) Grosvenor Bridge

For the best view of the bridge, head downhill in the car park towards the river and turn right towards the bridge, crossing under one of its vast arches. Look back to see a great view of the the entire span. For centuries the only bridge across the Dee at Chester was where the late Medieval Old Dee Bridge is now located, following the line established by the Roman bridge at the end of what is now Lower Bridge Street. This was becoming seriously congested by the 18th century, when both the population and the economy were growing at a considerable pace, and a new bridge was an urgent requirement. Local architect Thomas Harrison won the contract with his daring proposal for a 200ft (61m) single span that would not interrupt tall-masted river traffic. It was not merely a new artery for Chester, but a statement of civic pride. A plaque in the side of the bridge records that work began after an Act of Parliament was passed in 1825, and was paid for by a public loan of £50,000. It was opened by Princess Victoria on 17th October 1832 (5 years before she became Queen), and was paid for by tolls on both the Grosvenor and Old Dee bridges until 1885, when the tolls were abolished. The bridge remains a monumental and impressive sight today.

The Grosvenor Bridge shortly after construction. Source: Wikipedia

Retrace your steps and head back up the car park, passing in front of the cafe, and up the flight of steps to the Grosvenor Road, cross at the pedestrian lights, and turn left to walk over the bridge. [If you want to avoid the steps, head to the other end where the car entrance is, turn left and walk up the road, Castle Drive, to the head of the steps on the corner, and cross at the pedestrian lights and turn left across the bridge].

From the top of the bridge you can look right (or west) over the Roodee racecourse on the north bank of the river, and the impressive houses that formed the new middle class suburbs of Curzon Park which was developed in the 1840s to accommodate wealthy residents who wished to escape the narrower confines of the increasingly busy and commercial city. Some of the bigger of these buildings have been converted into apartments today. Look left (east) and you can see the spire of St Mary’s Without The Walls, as well as the Handbridge water tower, a local landmark that is visible from various points in the Chester area, and was influenced by Art Deco designs.

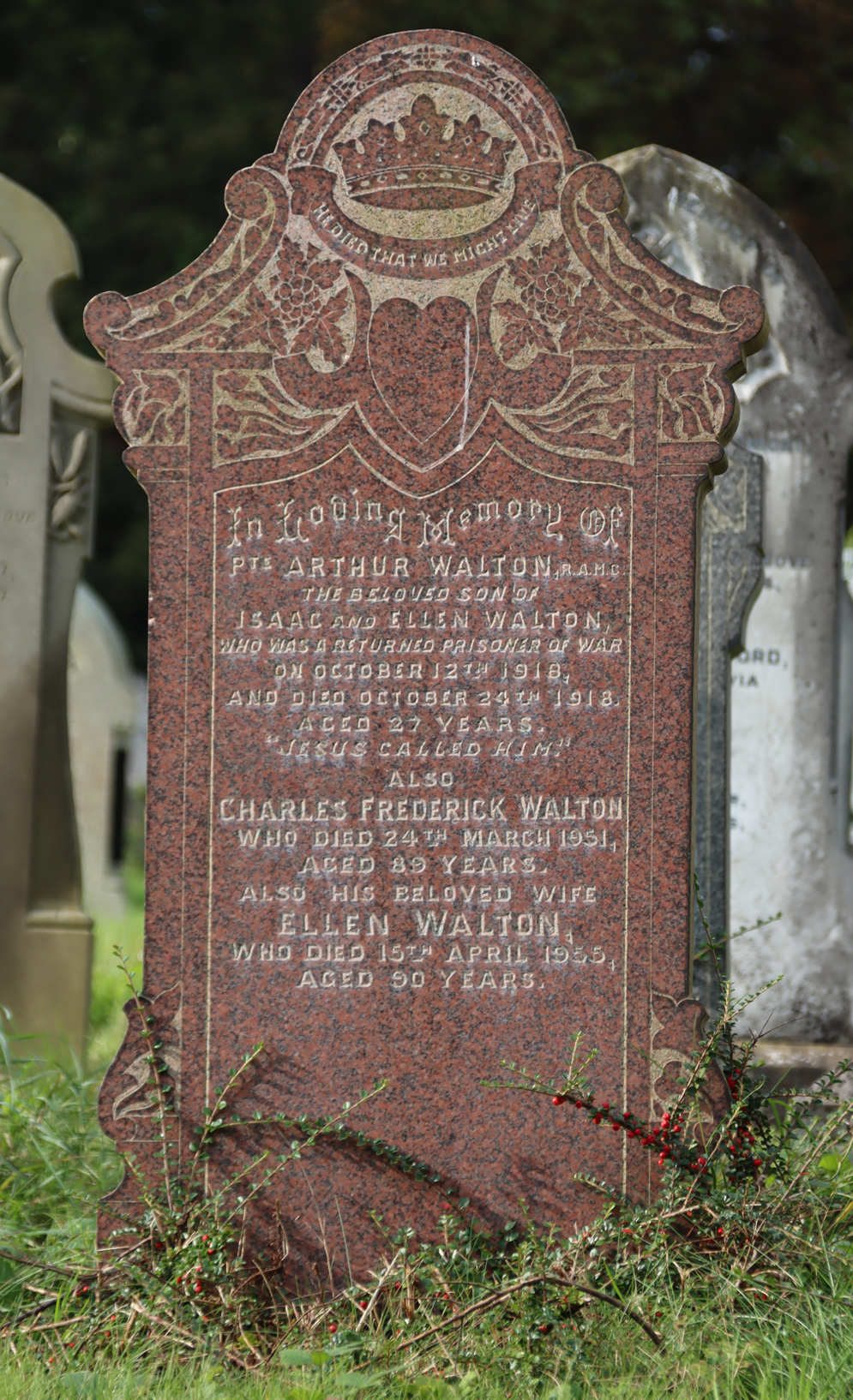

3) and 4) Three memorials in Overleigh Victorian Cemetery

After crossing the bridge, walk for perhaps 30 seconds and you will see a gateway on your left with wrought iron gates, one of which is open to provide access for pedestrians into the Victorian cemetery. If you are on the opposite side of the road, there is a traffic island almost opposite to make it easier to cross. Walk towards the information board and the bench, and pause. The walk will continue downhill to the right, but we are briefly detouring to the left to see two of the most interesting of the memorials in the cemetery, one of which is a puzzle until you see it on the early 1850s engraving of the cemetery.

xxx

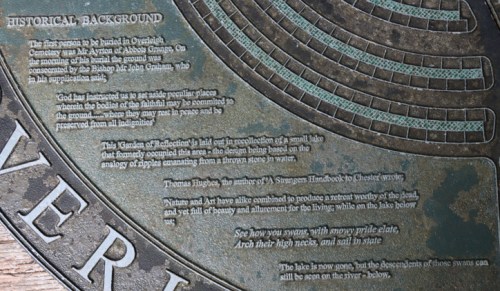

Overleigh cemetery was given the go-ahead by the Chester Cemetery Act in 1848. The land was acquired from the Marquis of Westminster, who exchanged it for a shareholding in the company. Work was forced to stop for seven months when the money raised was spent, and was not completed until new shareholders could be found. The cemetery opened in 1850. Like the Grosvenor Bridge, Overleigh Cemetery, was not merely the result of a Victorian efficiency drive and the desire to return a profit, but also a matter of improving the city in ways that demonstrated a profound interest in the character and status of the expanding city. Although the cemetery was a pragmatic response to the inability of churchyards to meet demand, the layout and planting of the cemetery reflect country house garden and leisure park designs, with curvilinear drives, gothic revival architecture, a lake, plenty of of trees of different types and a rustic bridge. Sadly, the only survivors of the architectural features from the 1850 design shown on the above engraving are the tall thin monument at far left, discussed below, and the rustic bridge at far right. You can read more about the cemetery and its fashionable and elegant design on the blog here.

Now head left past the bench and stop a few seconds away in front of a nicely executed faux Grade II listed Gothic shrine featuring an effigy beneath tan elaborate canopy. It puzzled me that there was no inscription on the shrine, but the actual grave ledger lies flat in front of the shrine over the top of the actual grave, complete with the elusive inscription. The shrine belongs to the Reverend Henry Raikes, who died in 1854, aged 72. The shrine was designed by architect Thomas Penson, who was the landscape architect for the entire cemetery and who built several buildings in Chester. It was erected in 1858, funded by public subscription, the progress of which was frequently reported in the local newspapers. As well as the former Chancellor of the Chester, Diocese Raikes was a philanthropist, a trustee and governor of the Blue Coat Hospital and one of the founders of the Chester “Ragged Schools” that provided education for pauper children.

Now head left past the bench and stop a few seconds away in front of a nicely executed faux Grade II listed Gothic shrine featuring an effigy beneath tan elaborate canopy. It puzzled me that there was no inscription on the shrine, but the actual grave ledger lies flat in front of the shrine over the top of the actual grave, complete with the elusive inscription. The shrine belongs to the Reverend Henry Raikes, who died in 1854, aged 72. The shrine was designed by architect Thomas Penson, who was the landscape architect for the entire cemetery and who built several buildings in Chester. It was erected in 1858, funded by public subscription, the progress of which was frequently reported in the local newspapers. As well as the former Chancellor of the Chester, Diocese Raikes was a philanthropist, a trustee and governor of the Blue Coat Hospital and one of the founders of the Chester “Ragged Schools” that provided education for pauper children.

Immediately to the right of the Raikes shrines, the second monument of note is the grave marker for Robert Turner (1790-1852), a Chester brewer and wine merchant who, in 1848 was Sheriff of Chester, a largely administrative but important function with the responsibility of keeping the peace, closely linked in to the work of the courts and the prison. The memorial as it stands today looks very peculiar, a bit like a three-tier cake on space-rocket jet nozzles. The clues to its original appearance actually still lie at its feet. Three stone columns lie horizontally, when not semi-concealed by undergrowth. Look at the engraving above and find the building at top right that looks like a little Classical temple. This is how the Turner grave marker originally looked. It collapsed at some time in the past, and the tiered roof and although it has been considerably tidied up, reconstruction is no longer possible, and this strangely truncated form is all that is left standing of the memorial monument.

Retrace your steps past the bench and head down the hill until you reach a tall monument (4) in a triangular intersection of the cemetery drives and pause to have a look at it.

Retrace your steps past the bench and head down the hill until you reach a tall monument (4) in a triangular intersection of the cemetery drives and pause to have a look at it.

This is not a burial monument but a memorial to William Makepeace Thackeray, 1790-1849, (uncle of the famous novelist) who moved from Denbigh to Chester to practice, and became a great success as a physician, and was renowned for his philanthropic and charitable works. He was buried in Chester Cathedral, but this memorial and its inscriptions celebrate his achievements, including “His attention to their charitable institutions / His consideration for the sick and needy / His kindness to the schoolboy and the orphan.” The memorial also serves as a useful anchor for the cemetery, a suitably impressive focal point that helps to give this part of the cemetery a sense of cohesion. This is also a very good position to pause and take in the wonderful selection of mature trees, most of which were planted when the cemetery was first laid out. There is a variety of species, and they were an essential part of the parks-and gardens style layout that was very popular in the Victorian period.

Head to the left. You will see the gateway pillars straight ahead of you. This opens on to River Lane. Turn left on to River Lane and turn right when you reach the end, heading east along the lovely River Walk. The walk from Overleigh to Edgar’s Field is a nice one, consisting of a metalled road flanked by trees and shrubs, with fields to the south and views of the river, depending on the time of year, to the north.

You will emerge from the path onto a short residential road, Greenway Street, and opposite is another gateway, this time into Edgar’s Field.

5) Edgar’s Field

Go through the gate into Edgar’s Field

Edgar’s Field is an open green space given to Handbridge by the first Duke of Westminster in 1892. The name Edgar, so the story goes, refers to the early medieval King Edgar, great-grandson of Alfred the Great, who was crowned King of England in both Bath and Chester. His Chester coronation was said to have followed a meeting near the field in AD 973, with leaders (either six or eight) from other regions after which he was rowed by members of the visiting delegation to St John’s Church, just a little further upriver. How much of this is legend and how much reality is anyone’s guess.

6) The sandstone outcrop

Straight ahead there is a choice of going uphill to the right or sticking to the river walk on the left.

Straight ahead there is a choice of going uphill to the right or sticking to the river walk on the left.

You will go right, but pause to look at the amazing sandstone outcrop. This is a particularly nice piece of bedrock, formed of sedimentary layers laid down, during the Triassic period, 252 to 201 million years ago, when the landscape consisted of Sahara-like desert and abraided rivers. This is also the period when the dinosaurs Pseuduchium Archosaur (ancestral to modern crocodiles and alligators) and Chirotherium are found, survivors of the Permian extinction (in which 95%) of dinosaurs were wiped out, and of which fossilized footprints have been found in the Triassic sandstones on Hilbre Island at the top of the Wirral.

The various lines and colours visible in the Edgar’s Field rock represent the different layers of sediment (bedding) that were laid down by rivers and floods that were laid down as muds and have built up over time. Nice features include both cross-bedding and slumping, geological features exclusive to sedimentary rocks. Differences in colour reflect differences in the chemical composition of the sediments as they were laid down, a dramatic example of which is shown in the above photograph of the outcrop. See more about the Cheshire sandstone in this PDF on the Sandstone Ridge Trust website.

Walk along the path to the right of the outcrop. A second outcrop appears on your right, and on the face that looks over the big open green is the Minerva shrine, so leave the path and walk up the green slope.

7) Edgar’s Field and the Minerva Shrine

When you are standing in front of the shrine, you will find it very water-eroded. It is carved directly into outcrop, one of only two known to be still in situ in Britain, and is a Grade II listed Scheduled Monument (1.45m high and 0.73m wide). The sandstone surround is Victorian in date, added in the hope of preventing further erosion.

When you are standing in front of the shrine, you will find it very water-eroded. It is carved directly into outcrop, one of only two known to be still in situ in Britain, and is a Grade II listed Scheduled Monument (1.45m high and 0.73m wide). The sandstone surround is Victorian in date, added in the hope of preventing further erosion.

The Roman 20th Legion, the Valeria Victrix, arrived in Chester (Deva) in AD76, and in one form or another the Romans remained in Deva until around 380. Although outside the Roman city walls, Handbridge was an important location because it was the quarry for the Roman town and its walls, the source of its red sandstone building blocks. Further along the path on an interpretation board is a reconstruction of what the shrine would have looked like, originally with an owl on Minerva’s left shoulder, possibly holding a shield in her left hand, and a spear in her right hand. Minerva was an interesting choice. Although better known goddess of wisdom and knowledge, she also served as a protector for those engaged in defensive war, a subtle distinction from aggressive war that might well be attractive to those building protective walls. The little cave to the right of the shrine was probably carved out to hold votive offerings. The area around the shrine was excavated in the early 1920s, revealing both that the quarry was in use at around AD100 and that subsequently soil was imported to cover the quarry floor in the late-second century. Roman occupation remains dating from that time on were found on the site. The site was again used as a quarry during the Middle Ages, when Historic England speculates that the Minerva carving may have been re-interpreted in Christian terms and re-used as a Christian shrine.

It is worth walking down to the edge of the river, through the line of magnificent lime trees, to enjoy the excellent views over the medieval Old Dee Bridge bridge. From there, follow the path for a short distance to the gates out of the park. You now have the Old Dee Bridge on your left and Handbridge on your right.

8) Handbridge

Handbridge has always has an extra-mural personality of its own. From the mid 12th century there were mills and quays at Handbridge, when parts of the district were owned by St Mary’s Benedictine nunnery, which seems to have taken over the entire manor by the 13th century. In the late 14th century industrial activity seems to have been represented by the production of glass, and by the 15th century it is thought to have been a popular area of Welsh migrant settlement. Welsh residents in the 16th century included a high percentage of the city’s brewers and ale sellers. In the Victorian era it became known as one of the poorer areas, with a high proportion of industrial worker. Today Handbridge has gone upmarket and is now an attractive residential location with a villagey-atmosphere, with some excellent cafés and pubs for those looking to take a break at this point. Both Spoilt for Choice and Brown Sugar cafés are great brunch/lunch stops, and the Old Ship Inn is a very fine pub.

Nathaniel Buck’s view of Handbridge in 1928. Source: MutualArt

9) The Old Dee Bridge

Do not cross the bridge, because the walk continues on the same side of the river, but if you want to stand in the middle and admire the weir, discussed next, it’s an excellent place for getting a good view.

The oldest known bridge to cross the river at this point was Roman, carrying the Via Praetoria from the south gate over the river to link up with the Roman road network, with roads leading directly from Chester to the southeast via Whitchurch to Wroxeter (Vicronium) and the south to London (Londinium) and Caerleon (Isca), and along the north Wales coast to Holyhead (Segontium). It must have been rebuilt several times over the 300 years of Roman occupation. The current late Medieval bridge replaces an early Norman bridge, but apparently fell down during the floods of 1227 and had to be replaced. The construction is interesting. It is built of the usual local red sandstone, but for reasons unknown, instead of being evenly distributed along the length of the bridge, the arches are each of a different width, giving it a splendidly individual appearance.

The Bridgegate on the opposite side of the river is discussed below.

10) The Weir

Staying on the same side of the river, cross the road and follow the line of the river for a few steps until you get a good view of the weir.

xxx

Very little is known about the weir itself. It is generally agreed that it was at least Norman in date, but whether it was actually the elaboration of a Roman innovation is open to debate. The Romans certainly built weirs, some of them very substantial, but at the moment there is insufficient information to determine the earliest date for it. Walk a little further down by the side of the river and you will see that on the near side of the weir there are a series of very wide water steps, forming what looks a little like a stepped waterfall; this is a salmon leap, built to enable the fish to navigate their way upstream for spawning. On an open day at the monitoring station last year I saw one of the salmon being caught for weighing and it looked huge!

Very little is known about the weir itself. It is generally agreed that it was at least Norman in date, but whether it was actually the elaboration of a Roman innovation is open to debate. The Romans certainly built weirs, some of them very substantial, but at the moment there is insufficient information to determine the earliest date for it. Walk a little further down by the side of the river and you will see that on the near side of the weir there are a series of very wide water steps, forming what looks a little like a stepped waterfall; this is a salmon leap, built to enable the fish to navigate their way upstream for spawning. On an open day at the monitoring station last year I saw one of the salmon being caught for weighing and it looked huge!

11) River monitoring station and ornamental water wheel

Probably the least attractive feature of the Chester riverside is a row of 1960s apartments that you will see from the north side of the river. You now pass under the concrete overhang of these apartments. There are lovely views over Chester on your left, and you will reach a small island with a building on it.

This is the river monitoring station, where various tests are carried out on the water quality and the condition of the fish themselves. I was lucky enough to be there on an open day last year when an enormous salmon was pulled out for weighing before being returned to its journey upstream. In front of it is a small water wheel, which was installed in the 1980s as a reminder of the former Dee mills that used to be a dominant feature of the medieval riverside and an all-important feature of Chester’s economy in the Middle Ages. Beyond it is a small sluice that once regulated water into the narrow channel that forms the island.

Carry on walking along the Riverside Walk, enjoying the greenery, until you reach the footbridge, which passes above the path, but has a flight of shallow steps running up either side of it so that you can reach the bridge from the path. [The alternative approach to the bridge, avoiding the steps from the river walk up to the bridge, is a rather long way round and is shown on the above maps as a dotted green line that takes you along Queens Park Road and around Victoria Crescent].

12) The lovely Queen’s Park footbridge

The 1923 bridge under construction. Source: Curiouser and Curiouser (Cheshire Archives and Local Studies blog)

In 1851 it was decided that Chester needed a second suburb, in addition to Curzon Park, to be named Queen’s Park, and this was developed throughout the 1850s. This was also built on the south bank of the river, this time opposite The Groves.

In 1852 a suspension footbridge was built to connect Queen’s Park with Chester, becoming the Queen’s Park Bridge. The predecessor of the current Queen’s Park footbridge was built in 1852. In 1922 this was taken down, and work began on a new suspension bridge that opened, with some ceremony, in April 1923. For more information about the opening of the bridge and its contemporary conditions of use, see the entry on the Cheshire Archives and Local Studies blog.

Conceptually, the bridge is the polar opposite of the vast solidity and monumentality of the later 1832 stone Grosvenor Bridge. The 1923 bridge is superbly elegant with delicate lattice metalwork. This latticing and the suspension cables supply a light, airy feeling, which is something to do with the sense of it hanging freely rather than being solidly rooted in the riverbed. It is a perfect partner for the light-hearted promenade known as The Groves, with its lovely buildings and the similarly elegant bandstand, which is still used today, and the little ice-cream turrets. Pride in the achievement, common to so many Victorian enterprises, is declared in the panels at the top of the suspension towers, which give the name of the bridge and the date of its construction. Just as on the Grosvenor Park Lodge, the bridge’s towers feature the shields of Chester’s Norman earls.

Conceptually, the bridge is the polar opposite of the vast solidity and monumentality of the later 1832 stone Grosvenor Bridge. The 1923 bridge is superbly elegant with delicate lattice metalwork. This latticing and the suspension cables supply a light, airy feeling, which is something to do with the sense of it hanging freely rather than being solidly rooted in the riverbed. It is a perfect partner for the light-hearted promenade known as The Groves, with its lovely buildings and the similarly elegant bandstand, which is still used today, and the little ice-cream turrets. Pride in the achievement, common to so many Victorian enterprises, is declared in the panels at the top of the suspension towers, which give the name of the bridge and the date of its construction. Just as on the Grosvenor Park Lodge, the bridge’s towers feature the shields of Chester’s Norman earls.

13) The Grosvenor Park

Walking off the bridge on the Chester side you will see a flight of steps straight ahead of you. Just before the steps, on your right, is the understated gateway into the Grosvenor Park.

I have included the park partly because it surprises me how many residents and visitors seem to bypass it, and it is lovely on a sunny day. The Grosvenor Park was the brainchild of Richard, the second the Marquis of Westminster, following the example of similar projects elsewhere. Like many wealthy Victorians, he undertook a number of philanthropic projects, and in 1867 the park opened for the benefit of local Chester inhabitants. Unlike many town and city parks this one was not paid for partly by subscription; it was, in its entirety, a gift to the city from the Marquis, who chose the designer of the successful Birkenhead Park, landscape architect Edward Kemp (1817-1891), to lay out his new public space.

Today it is a beautifully maintained space with a miniature railway operating in the summer, a rose garden, a couple of vantage points from which to inspect the views over the river and some lovely wide open spaces, together with the shade of trees for those who prefer a bit of cover, in which to relax. Although this is not a formal park, in terms of the big municipal floral plantings that characterize some English parks, there are colourful beds dotted around and at the top left corner of the park there is a charming wheel-shaped rose garden that is lovely in the summer months, with a variety of colours, and some lovely scented species, with benches around its edges. As in the cemetery, which had opened 17 years previously, the trees were seen as a major feature of park and there are some splendid specimens. The pond may once have been ornamental, but is now surrounded by tall reeds, providing a splendid refuge for wildlife. I have seen the rails for the miniature railway but not the train – I really must find out when it runs! There is plenty of seating throughout the park, and as well as permanent sculptural pieces, there are often temporary modern art installations dotted throughout, which may or may not be your cup of tea, but are always genuinely interesting, and usually reference the natural world. Look out for information panels dotted throughout the park. The lodge, discussed next, serves as a coffee shop during the summer. It’s not on the map because it is closed in the winter.

Today it is a beautifully maintained space with a miniature railway operating in the summer, a rose garden, a couple of vantage points from which to inspect the views over the river and some lovely wide open spaces, together with the shade of trees for those who prefer a bit of cover, in which to relax. Although this is not a formal park, in terms of the big municipal floral plantings that characterize some English parks, there are colourful beds dotted around and at the top left corner of the park there is a charming wheel-shaped rose garden that is lovely in the summer months, with a variety of colours, and some lovely scented species, with benches around its edges. As in the cemetery, which had opened 17 years previously, the trees were seen as a major feature of park and there are some splendid specimens. The pond may once have been ornamental, but is now surrounded by tall reeds, providing a splendid refuge for wildlife. I have seen the rails for the miniature railway but not the train – I really must find out when it runs! There is plenty of seating throughout the park, and as well as permanent sculptural pieces, there are often temporary modern art installations dotted throughout, which may or may not be your cup of tea, but are always genuinely interesting, and usually reference the natural world. Look out for information panels dotted throughout the park. The lodge, discussed next, serves as a coffee shop during the summer. It’s not on the map because it is closed in the winter.

14) Four Medieval monuments

As you walk into the park along a metalled path, you will soon come to a set of three clearly medieval (as opposed to mock-gothic) monuments set back from the main path, with a little side path of its own. These were all moved here from elsewhere in Chester, and serves as a miniature outdoor museum. The first one that you encounter is a gothic arch from St Michael’s Church, which is still standing but was largely rebuilt in the 1840s by James Harrison, and it is possible that the gateway was removed at that time.

Next, following the side path is the little Jacob’s Well, originally installed on The Groves as a drinking fountain and at its base a water dish for dogs. The keystone inscription is from the New Testament and reads “Whosoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again.” Finally, and most impressive of the three, is the arch and flanking niches that once linked the nave of St Mary’s monastic church to its chancel, a sad reminder of the absolute total loss of St Mary’s medieval nunnery. The photograph of it is below under no.27, where the nunnery is discussed.

xxx

Keep walking across the intersection, bearing right, and you will immediately come across the Ship Gate, which once sat to the west of the Bridgegate at the end of Lower Bridge Street providing pedestrian access from the riverside to the city. This was moved three times, first in 1831 to a private garden in the Abbey Square, next in 1897 to the Groves and finally in 1923 to its present location in Grosvenor Park.

Between the St Mary’s arch and the Ship Gate there is a path going uphill to the main park, with handrails, shown in the photograph above. Walk up the slope to the main drive towards the statue at the end.

15) Viewing platform over the Dee

If you follow the main drive to the statue of Richard, the second the Marquis of Westminster, you will see, slightly to your right, a large viewing platform with seating around its circuit. The view over Chester meadows towards Boughton was probably a bit better in the late 1800s, but is still good today.

If you follow the main drive to the statue of Richard, the second the Marquis of Westminster, you will see, slightly to your right, a large viewing platform with seating around its circuit. The view over Chester meadows towards Boughton was probably a bit better in the late 1800s, but is still good today.

16) Grosvenor Park Lodge

When the park was opened in 1867, it had a lodge at the main gate and this remains today, used as a café in the summer months. It was designed by successful local architect John Douglas who is best known for the Eastgate Clock, but who built a great many buildings in different styles in Chester. It was built in the popular half-timbered revival style over red sandstone. The brightly coloured statuettes on black timbers on the lodge show King William I, who appointed Hugh d’Avranches, better known as Hugh Lupus as the first Earl of Chester from 1071 until his death in 1101. Hugh is shown, together with the successive Earls of Chester, ending with John de Scot (from 1232 to 1237), who died without heirs, after which the earldom reverted to the Crown. Various family shields show locally relevant themes including the golden sheaf of the Grosvenor family, the portcullis of Westminster and the Chester city coat of arms.

When the park was opened in 1867, it had a lodge at the main gate and this remains today, used as a café in the summer months. It was designed by successful local architect John Douglas who is best known for the Eastgate Clock, but who built a great many buildings in different styles in Chester. It was built in the popular half-timbered revival style over red sandstone. The brightly coloured statuettes on black timbers on the lodge show King William I, who appointed Hugh d’Avranches, better known as Hugh Lupus as the first Earl of Chester from 1071 until his death in 1101. Hugh is shown, together with the successive Earls of Chester, ending with John de Scot (from 1232 to 1237), who died without heirs, after which the earldom reverted to the Crown. Various family shields show locally relevant themes including the golden sheaf of the Grosvenor family, the portcullis of Westminster and the Chester city coat of arms.

17) The Grosvenor Park Archaeological Excavation

Near to the rose garden, to its east, and for several weeks every year since 2007, an archaeological excavation takes place using students of the University of Chester to investigate the complex historical narrative of this area. The project was initiated to provide information about the Church of St John the Baptist, and the later use of the area, including a house documented to have been built in the late 1500s by Sir Hugh Cholmondeley which was later destroyed in the English Civil War. At the same time, given the proximity of the Roman amphitheatre on the other side of St John’s, it was hoped that some information pertaining to extra-mural activities under the Romans might emerge, and how the position and ruins of the amphitheatre, as well as the influence of the church, impacted on the later use and development of the surrounding area. In 2025 the excavation took place between during May. Visitors can see the excavation taking place, and the site directors and supervisors are very happy to answer any questions from the public. An excavation Open Day is always organized towards the end of the excavation too.

18) The ruins of the east end of St John’s Church

Leaving the park at the west, where the exit puts you on the path that leads back down to the footbridge, you find yourself at the east end of St John the Baptist’s Church.

St John the Baptist’s Church, marked with a green star next to the number 18, has a long and fascinating history, which is far too complicated to deal with here. The current church was established in the 11th century outside the city walls and was the original Chester Cathedral and a collegiate church. Its architecture is splendidly dominated by the Romanesque, featuring vast columns and gloriously rounded arches, has a wonderful if faint painted fresco, and contains a fine collection of early medieval stone funerary memorials. Its monumental sense of indestructibility is somewhat misleading, however, as its tower came down in its entirety on Good Friday in 1881.

Without going into the church, however, you can wander around the ruins at the east end of the church. There are plenty of information boards to explain what is going on, but the short version is that in the mid-1500s the church was too large for the congregation and the decision was made to truncate it by sealing off the eastern end which, deprived of its roof, rapidly deteriorated into ruins. These ruins contain a splendid Norman arch, which once gave access to the chancel, as well as the usual gothic lancet (pointed) arches, shown in George Cuitt’s engraving below. One of the other of the many features is the puzzling inclusion of an oak coffin at the top of one of the gothic arches, facing outward, shown above left.

The ruins of St John’s in the first half of the 19th century, showing a splendid Norman Romanesque arch in the foreground, which still stands, and a gothic lancet arch in the background. By George Cuitt

19) The Anchorite Cell / Hermitage

Just downhill from St John’s, at the base of the steps [or thread your way back through the east end of the park by taking left turns, back to the entrance at the bridge], look over the fence on your right to see the lovely so-called anchorite cell, Grade II listed.

The lovely little building sits on an outcrop of red sandstone bedrock. An anchorite is a religious recluse, someone who decides to retreat from all form of society, even monastic, to pursue a life of prayer and devotion. The building seems to correspond to a number of references to an anchorite chapel and cell dedicated to St James in the cemetery of St John the Baptist’s church, opposite the south door.

The earliest story, unsubstantiated (and generally discredited), comes from the priest-historian Gerald of Wales (d.1223), who records that King Harold II was not killed at the Battle of Hastings, but was wounded and fled to Chester, where he lived at the cell (or hermitage) for the rest of his life. British History Online says that this was the only such building that seems to have had a degree of permanence: “In the mid 14th century it held monks of Vale Royal (1342) and Norton (1356) and a Dominican friar (1363), and in 1565 a lease of property formerly belonging to St. John’s College included the ‘anker’s chapel’.” The Freemen and Guilds of The City of Chester website mentions that at some point the building was used by the cordwainer guild (shoemakers) as a weekly meeting place “until they sold it in due course to a Mr Orange, and spent the proceeds on a party,” but provides no date. It was expanded in the late 19th century, when the porch of the recently demolished St Martin’s Church, which was being demolished, was moved to form a new north entrance. It was renovated in the early 1970s, but I can find no mention of how it is being used today.

20) and 21) The Groves

The Groves are a Victorian invention. The earliest section is The Groves East, which has some very attractive residential buildings facing the river, including an Italianate terrace, a Georgian-style terrace built in the early Victorian period and the revival half-timber rowing club boathouse, as well as cafés and pubs. There are some good views over the riverside buildings on the edge of Queen’s Park, opposite. Between 1880 and 1881 the western section that is most obviously a promenade area was laid out by Alderman Charles Brown.

The Groves are a Victorian invention. The earliest section is The Groves East, which has some very attractive residential buildings facing the river, including an Italianate terrace, a Georgian-style terrace built in the early Victorian period and the revival half-timber rowing club boathouse, as well as cafés and pubs. There are some good views over the riverside buildings on the edge of Queen’s Park, opposite. Between 1880 and 1881 the western section that is most obviously a promenade area was laid out by Alderman Charles Brown.

A s well as the lovely Grade II listed bandstand and delightful little octagonal ice cream huts, the city walls are particularly impressive here, towering above the river with some big chunks of bedrock at their base. From here you can also enter the Roman Gardens (shown on the map with a green star), by following the line of the wall into a corridor between the wall and a restaurant. Just about where the no.21 is marked on the above map is a flight of steps leading up to the walls. These are known as the Recorder’s Steps, built in around 1720, linking the walls and the fashionable promenade to provide ease of access. If you want to continue your walk by doing a circuit of the walls, this is a very good place to start, particularly as there is a map of the walls at the bottom of the steps. The walls either side of the stairs are an interesting mix of different periods of construction, with one or two puzzling features.

s well as the lovely Grade II listed bandstand and delightful little octagonal ice cream huts, the city walls are particularly impressive here, towering above the river with some big chunks of bedrock at their base. From here you can also enter the Roman Gardens (shown on the map with a green star), by following the line of the wall into a corridor between the wall and a restaurant. Just about where the no.21 is marked on the above map is a flight of steps leading up to the walls. These are known as the Recorder’s Steps, built in around 1720, linking the walls and the fashionable promenade to provide ease of access. If you want to continue your walk by doing a circuit of the walls, this is a very good place to start, particularly as there is a map of the walls at the bottom of the steps. The walls either side of the stairs are an interesting mix of different periods of construction, with one or two puzzling features.

The most attractive of all the public toilet buildings in Chester! The Groves West, opposite the bandstand.

As you walk towards the Old Dee Bridge, look over the river to see the concrete apartments under which you you walked earlier. These, in the so-called Brutalist style, are the “Salmon Leap” buildings and were built starting in the late 1960s until the mid 1970s, which look rather like a bar code. In the interests of naming and shaming, they were designed by Liverpool architects Gilling Dod and Partners from Liverpool. I recall that when I was visiting my parents once, many years ago, they were painted pink (salmon pink??), which was indescribably bad.

As you walk towards the Old Dee Bridge, look over the river to see the concrete apartments under which you you walked earlier. These, in the so-called Brutalist style, are the “Salmon Leap” buildings and were built starting in the late 1960s until the mid 1970s, which look rather like a bar code. In the interests of naming and shaming, they were designed by Liverpool architects Gilling Dod and Partners from Liverpool. I recall that when I was visiting my parents once, many years ago, they were painted pink (salmon pink??), which was indescribably bad.

22) The Bridgegate

Nathaniel Buck’s Old Dee Bridge, showing the Bridgegate with the massive 1600 water tower as it was in 1728. Source: MutualArt

Today’s Georgian gateway, carrying the walls over Lower Bridge Street, is the latest iteration of the first gate built here by the Romans to defend access to the Via Praetoria. By the Middle Ages all the bridge’s predecessors had been replaced by a medieval gateway that had a central pointed arch, which carried the walkway, and was flanked by two round towers. This was quite an understated affair, but became considerably more noticeable when a tall, slender water tower was added to the west tower in 1600 to pump water from the river into the city (shown on the above image). It was destroyed during the Civil War, but is recorded in earlier engravings. The medieval Ship Gate, one of the architectural features preserved in Grosvenor Park, was a pedestrian archway giving access to the city Just to the west of the Bridgegate (towards the car park), which has already been mentioned in connection with the Grosvenor Park, where it was moved in the 1830s.

On the city side of the Bridgegate, on your left as you look uphill, is the Bear and Billet public house, which looks like one of the original half-timbered buildings but is in fact part of the revival of timber-framed buildings after the Civil War, in which multiple buildings were destroyed, and was built in 1664 for the Earl of Shrewsbury. See the picture near the end of the post in Sources.

As Chester’s population expanded during the 1700s, the increasing size of vehicles and the need for two-way traffic to pass into and out of the area defined by the walls resulted in the destruction and replacement of the medieval bridge. The yellow sandstone Georgian arch that survives today was built in 1782 to a design by Joseph Turner (c.1729–1807), a successful local architect. It supports a walkway that connects the two parts of the city walls that flank Lower Bridge Street. Although not particularly imaginative, it is elegant in a typically Georgian way.

23) The Dee Mills and the hydroelectric station

The Old Dee Mills in the 19th Century, with the Bridge Gate to its right and the Old Dee Bridge at its side. Source: Chesterwiki

The area around the Old Dee Bridge was busy from the Roman period onwards. In the Middle Ages this part of the river was the site of several water mills, and mills continued to be built here until the last one burned down in 1895 and was knocked down in 1910. In 1913 the site was used to establish a hydroelectric station, part of which survives in the form of the gothic-style building that sits below the bridge in the corner with the north bank, but this went out of use in 1951 and is currently vacant. You can still see the hydroelectric station in situ on the walk, and the Ship Gate is still visible in the Grosvenor park (photograph further up the page at no.14), but the mill is only preserved in pictures.

24) Prison wall

The remains of the west side of the river wall of the former prison, with its distinctive arches, next to the Wheeler Building.

Although it is captured in paintings and engravings, there’s almost nothing left of the former prison, although it was a very substantial building in its day. Both the prison and the river wall with its inset arches can be seen on this painting below by prolific local artist Louise Rayner (1832-1934). All that remains is the former river wall with its inset arches, and even this is a matter of noticing that it is there, rather than actually seeing it, even from the opposite side of the river, as it is hidden by extensive tree growth. It is marked by the fact that it projects slightly into the river. There are two places where the inset arches are visible, first by the railings opposite the Wheeler Building, where you can lean over and look back, and rather more accessibly there is small a section to the side of the Wheeler Building, which carries the path back up on to the walls, shown here. Up until 1785 the prison was based in the Chester Castle dungeons, but by the mid-18th century it was very clear that this was no longer fit for purpose, and when it was decided to build a new prison, architects were invited to submit designs to a competition. Thomas Harrison, who is mentioned below in connection with the revitalization of the castle, won the contract, and new riverside prison opened in 1793. Less than a century later, in 1865, it was unable to cope with demand, and it was rebuilt, opening again in 1869. It was demolished in 1902.

25) The Wheeler Building, housing Royal Infirmary Stained Glass and the Riverside Museum

The University of Chester’s Wheeler Building, a vast block of a thing on your right as you head towards the Little Roodee car park, was built in 1857 as the former Cheshire County Council headquarters. Although there is not much to say about it as a piece of architectural heritage, it does contain two really valuable items of local heritage interest. On the first floor of Wheeler Building you can find the stained glass that was once installed in the Victorian Royal Infirmary (opened in 1761, closed in 1994 was converted for residential use in 1998), and about which you can read more on the Chester Archaeological Society blog here. The Riverside Museum, which usually opens only once a month, is a permanent collection of curiosities from the world of medicine, nursing, midwifery and social work, in addition to an original letter written by Florence Nightingale from Balaclava.

Just past the Wheeler Building, you can walk up the path that follows a slope up the old prison walls onto the city walls for the last stretch of the walk. If you take the opportunity, you get some views over the river, and the best angle to see this side of the castle. [There are no steps upto and off this stretch of the walls, but if you have a wheelchair or buggy, there is a dogleg turn that may be difficult to negotiate]

26) The Castle

Chester Castle today is a bizarre and not terribly attractive mixture of Neoclassical and medieval when seen from the front. The original castle following the Conquest of 1066 was a timber-built motte-and-bailey castle, but this was replaced by the medieval stone castle in the late 12th century. The Neoclassical bolt-on was architect Thomas Harrison’s solution to the dilapidated state of the building in the Georgian period.

From the walkway along the walls you can see the square Agricola Tower, which dates from around 1190-1200, and this and the Flag Tower are the only survivors of this early stone-built castle. The tower is opened at least once a year for visitors to see around the vaulted chapel and 13th century wall paintings that are thought to have been ordered by Edward I for his use of the castle as a base during his negotiations with the Welsh princes. That’s high on my to-do list.

Leaving the walls, you can walk up to the entrance to the castle if you want to see the view from the entrance. Otherwise, cross the road at the pedestrian lights, taking note of the big black modern building squatting on your right as you cross the road and go a short distance to the covered viewing point, where there are interpretation boards, and have a look over the Roodee.

Nathaniel Buck’s 1728 engraving of the castle. Source: chesterwalls.info

27) The Roodee and the site of St Mary’s Nunnery

Nathaniel Buck’s Prospect of the City of Chester 1728 showing The Roodee. Source: chesterwalls.info

The Roodee is now home to the Chester racecourse, with the earliest race here held in 1539, but it also formed the edge of a river port second in size to Bristol on the western coast of Britain, supporting a successful trade along the coast and across to Ireland, as well as a thriving shipbuilding industry. The commercial value of the river began to decline at the end of the 18th century as the river began to silt up, and did not survive the 19th century. However, the archaeology of the river at the Roodee dates back to at least the Roman period when there was a harbour at the river and excavations in 1885 revealed the remains of a jetty near the railway viaduct. The above engraving by Nathaniel Buck shows the medieval tower, connected to the walls by a fortified walkway, which was once at the water’s edge, demonstrating how silting was impacting the port of Chester even at this stage.

Turn so that your back is to the Roodee. Over the road was the site of St Mary’s Benedictine Nunnery.

Turn so that your back is to the Roodee. Over the road was the site of St Mary’s Benedictine Nunnery.

St Mary’s Convent was founded in 1140 and survived until the Dissolution in 1535,on the north side of today’s Nun’s Lane, which is the small road that runs along the top of the Roodee and the race course. It was built just inside the city walls, a little to the west of the castle. This became quite a large monastic establishment with a relatively compact cloister around which were the usual domestic and administrative buildings along three sides, with the monastic church on the fourth side, and a larger separate courtyard with more buildings arranged around it. A double-cloister arrangement was not at all unusual in wealthy monastic establishments, but the nunnery was notable for its financial difficulties even though it owned and rented out several properties in Chester, and from the 13th century owned the manor of Handbridge. The last surviving piece of architecture from the nunnery survives in Grosvenor Park, which preserves the red sandstone arch and flanking niches that once separated the church’s nave from its chancel.

The black glass and red sandstone building on the other side of Nun’s Lane, Abode (built in 2010), replaces the former police headquarters, which was an eyesore of a very different type, and between the police building being knocked down and Adobe being built, an archaeological excavation took place. As well as what are thought to have been significant Roman discoveries, the remains of the nunnery were excavated, producing both architectural and funerary remains, as well as discarded objects. Quite who was responsible for seeing that the excavation records were published I don’t know, but one of the great tragedies of Chester heritage was that the small company responsible for the excavations never did publish, and no-one seems to know where the excavation reports and any preserved materials might be located.

The remains of St Mary’s Nunnery in 1727. Source: British History Online

After the 1536 Dissolution, when the nuns dispersed, the land and buildings were granted to a member of the Brereton family, in whose hands it remained until the 17th century. Its best known resident was Sir William Brereton, who was the Cheshire commander of the Parliamentary forces during the Civil War, when the buildings came under fire, were badly damaged and were never repaired. As ruins on valuable land within the city walls they were soon replaced. At the west end of the former site, architect Thomas Harrison, who has been mentioned several times above, built St Martin’s Lodge for his own use, now sympathetically converted into the gastro pub The Architect.

The walk is over! Retrace your steps back over the Grosvenor Road into the car park, either via the steps on the corner, or down Castle Drive and into the main entrance, which avoids steps.

xxx

Final comments

I particularly like this walk because of the sheer amount of diversity that it introduces to the experience of Chester, beyond what you can find on a walk around the walls or a stroll around the main streets and the rows. This is a slightly different slant on Chester, one that takes place nearly entirely beyond the walls, where there is space for promenades, open green spaces, a massive race course, a Victorian cemetery, river walks and of course some marvellous bridges and views over the surrounding area. Neither urban nor suburban, this walk focuses on the in-between borderland of the riverside.

The shortlink for this post is: https://wp.me/pcZwQK-7BG

Braun’s Map of Chester, 1571 showing the RooDee with a grazing cow at left, Handrbidge at the bottom, and the Old Dee Bridge connecting Handbridge with the Bridgegate. Source: chesterwalls.info

Sources

Books and Papers

Boughton, Peter 1997. Picturesque Chester. Phillimore

Carrington, Peter 1994. Chester. English Heritage

Cheshire West and Chester Council 2012. Explore the Walls. A circular walk around Chester’s historic City Walls. Cheshire West and Chester Council

Clarke, Catherine A.M. 2011. Mapping the Medieval City. Space, Place and Identity in Chester c.1200-1600. University of Wales

Herson, John 1996. Victorian History: A City of Change and Ambiguity. In (ed.) Roger Swift. Victorian Chester. Liverpool University Press

King, Michael J. and David B. Thompson 2000. Triassic vertebrate footprints from the Sherwood Sandstone Group, Hilbre, Wirral, northwest England. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association,

Volume 111, Issue 2, 2000, p.111-132

Langtree, Stephen and Alan Comyns (eds.) 2001. 2000 Years of Building: Chester’s Architectural Legacy. Chester Civic Trust

Laughton, Jane 2008. Life in a Late Medieval City. Chester 1275-1520. Oxbow

Martin, Richard 2018. Ships of the Chester River. Bridge Books

Mason, D.J.P. 2001, 2007. Roman Chester. City of the Eagles. Tempus

Mason, D.J.P. 2007. Chester AD 400-1066. From Roman Fortress to English Town. Tempus.

Ward, Simon 2009, 2013. Chester. A History. The History Press

Websites

Based in Churton

Overleigh Cemetery in Chester, Parts 1 and 2 by Andie Byrnes

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/category/overleigh-cemetery/

British History Online

Religious houses: Introduction

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/ches/vol3/pp124-127

The Cheshire Sandstone Ridge

The geology of the mid Cheshire Sandstone Ridge: Our landscape story

https://www.sandstoneridge.org.uk/lib/F715451.pdf

Chester Characterisation Study

St John’s Character Area Assessment

https://www.cheshirewestandchester.gov.uk/asset-library/planning-policy/chester-characterisation-study/e-chestercharacterisationstudystjohns.pdf

Chester Heritage Festival YouTube Channel

Four Minute Wonder: The Sandstone Outcrop by Paul Hyde, 2024

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxgoKh_4FXk

Four Minute Wonder: The Grosvenor Park Lodge by Paul Hyde, 2024

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Td67domdAWQ

Chesterwiki

River Dee Geology

https://chester.shoutwiki.com/wiki/River_Dee_Geology

Curiouser and Curioser: Tales from Cheshire Archives and Local Studies

A Grand Day Out in Chester: celebrating 100 years of the new Queens Park Suspension Bridge

https://cheshirero.blogspot.com/2023/04/a-grand-day-out-in-chester-celebrating.html

The Freemen and Guilds of the City of Chester

Cordwainers

https://chesterfreemenandguilds.org.uk/about/

Heritage Gateway

Post Dissolution Use of Former Benedictine Nunnery

https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MCH18993&resourceID=1004

Historic England

Roman quarry including Edgar’s Cave and the rock-cut figure of Minerva on Edgar’s Field, 150m south west of Dee Bridge

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1014718

The Hermitage, The Groves

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1375947

The Spoonster Sprouts

Brutalist Architecture in Chester: A Guide. By Tom Spooner, 15th July 2024

https://thespoonsterspouts.com/brutalism/chester-brutalist-architecture/

A Virtual Stroll Around the Walls of Chester

Old Maps and Aerial Photographs of Chester – Nathaniel Buck

https://chesterwalls.info/gallery/oldmaps/prospect.html

Wikipedia

Henry Raikes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Raikes

Upcoming

The Historic Towns Trust map for Chester should be a great aid to anyone planning their own heritage walk. Although I have one on order it hasn’t arrived yet. You can find details on the Trust’s website where you can also order a copy:

https://www.historictownstrust.uk/maps/an-historical-map-of-chester

View of the City of Chester by an unknown artist, mid 1700s. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum, accession number 29635:57

Nathaniel Buck’s South West Prospect of the City of Chester, 1728. Source: Mutual Art