Introduction

Plas Newydd and the Gorsedd Circle seen from a high vantage point. Source: RCAHMW

In the garden at Plas Newydd in Llangollen a 60ft (18.3m) diameter stone circle with a large stone at its centre is partially overlooked by some rather nice topiary. It is probably no surprise that the stone circle is not prehistoric, because it would be infinitely better known if it was, and a real tourist attraction in its own right. It was built in 1907 to host the Proclamation ceremony that preceded the 1908 National Eisteddfod. During the 1908 Eisteddfod it had a specific ceremonial function. The circles used during the eisteddfodau (plural of eisteddfod) are known as cerrig yr orsedd (stones of the throne or Gorsedd circle), which refers to the Gorsedd ceremonies that take place within the circle, and which are explained below. When Mr George Robertson, who owned Plas Newydd in 1908, agreed to host the Gorsedd circle and decided to make it a permanent addition, he added a new aspect to Plas Newydd both at the time and for perpetuity. Brand new at the time of its creation, and part of a tradition that had only been established in 1819, it has now become a piece of heritage in its own right.

This post looks at what a Gorsedd stone circle represents and how its particular character contributes to the eisteddfod tradition, and then describes how the Plas Newydd circle was assembled and used and what it means today.

I did the background reading for this piece as much for myself as for readers, because I had only the fuzziest view of what an eisteddfod might be, how it related to the national and, on the other hand, the international events, and what on earth a Gorsedd might be. It turns out that this takes rather a long time. I have tried to tackle the terms and their histories succinctly but clearly below. All sources are listed at the end. If you would prefer a PDF version without images (except for two that are necessary to show the layout of the circle) please get in touch.

Throughout the post I have used eisteddfod with a small “e” to refer to local and provincial events, and with a capital “E” to refer to the National Eisteddfodau.

You can find parts 1-3 of this series on the fabulous Plas Newydd, the house shown in the photograph above, by clicking here.

- Developing a rich Welsh cultural heritage

- The growth of the eisteddfodau

- The example of the 1908 Llangollen Eisteddfod

- The Plas Newydd Gorsedd Circle

- The Question of Authenticity

- Final Comments

- Visiting

- Sources

xxx

Developing a rich Welsh cultural heritage

Before a discussion of the Gorsedd circle is possible, a few concepts from Welsh cultural history need to be addressed. The Gorsedd circle is only one component of an event called the Eisteddfod, with a specific ceremonial role within that event, connected to the bardic tradition of Wales. These terms, foreign to many who live outside Wales, are an essential part of the language of Welsh literature and song, and are explored below.

Eisteddfod

David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill at the 1908 Llangollen Eisteddfod

When David Lloyd George visited Snowdonia in 1908, in the company of Winston Churchill, he visited the Llangollen Eisteddfod. He spoke in the pavilion about the power of the mountains, the valleys and the rich cultural history of his homeland. It is this sort of perceived power of the Welsh landscape and its history that formed the basis of some of the early ideas about the heritage of the eisteddfodau and what they might achieve. Lord Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth is usually credited with having ordered the first formal competitive eisteddfod 1176 to take place at Cardigan Castle. The word eisteddfod is made up of two terms eistedd (sit) and fod (be), which, according to Hywel Teifi Edwards translates roughly as “sitting together” and is a type of local festival, fair and pageant celebrating Welsh music, literature, theatre and language. In the 18th century the growing perception of the importance of Welsh culture to Welsh identity resulted in a number of new initiatives and organizations, and resulted in a renewed interest in the eisteddfod as an engine of Welsh cultural progress.

The eisteddfod, being a non-political but vibrant statement of Welsh pride in its literary and musical traditions, became an important tool for promoting Welsh solidarity and supporting the sustainability of Welsh cultural traditions and language. At the conclusion of the 1908 Llangollen National Eisteddfod it was concluded that one of the positive features of the event was that the Eisteddfod has a great education value as well as supporting Welsh culture. The Bishop of St Asaph took up this theme at the 1908 Llangollen Eisteddfod, saying that the Eisteddfod not only rewarded excellence but encouraged those that aspire to excellence, pointing out that the competition was open to poor and rich alike, and accessible to those who were self-taught as well as those who had attended seats of higher learning.

Every town to host a National Eisteddfod host is selected two years in advance of the event, and the date and competitions to take place are announced at a Proclamation Ceremony (Gorsedd y Cyhoeddiad) at least a year and a day in advance of the actual opening ceremony. The stone circle, whether temporary or permanent, is required at the time of the Proclamation so that the ceremony can take place within it, before being once again needed for the opening ceremony a year later. This system of formal proclamation echoes Lord Rhys’s own 1175 proclamation for the 1176 eisteddfod, announced a year in advance to allow competitors to prepare. The development of local and provincial eisteddfodau into the National Eisteddfod is discussed below. Local, provincial and national eisteddfodau could all occur simultaneously, each with its own goals in mind.

The bards

Proclamation Ceremony at a tiny symbolic Gorsedd circle in 1888 at Brecon

The revived eisteddfod celebrated the bardic tradtion. The earliest use of the term “bard” refers to Welsh-language poets who, in the medieval period, were professional poets, and usually maintained their professions by being itinerant. They were honoured guests at the homes of nobility and in monastic premises as orators of poetic forms including poetic versions of accepted history. The best of these bards were widely lauded, valued members of society and are referred to extensively in medieval literature. Guto’r Glyn, for example, was a famous 15th century bard who lived for a time at Valle Crucis Abbey, just outside Llangollen, and wrote about the architecture as well as the hospitality he received whilst there in flattering terms (see, for example, the Valle Crucis page on the Guto’s Wales website). Whilst this type of poetry was undoubtedly entertainment, it was also a form of artistic endeavour and was recognized as such. Bards often performed at local eisteddfodau where winning prizes helped to establish them in bardic circles, but rarely beyond. By the later 18th century, when the eisteddfod became associated with the Gorsedd ceremonies, many of the bards were working class and would have had full time professions, writing in their spare time. A bard would usually have two names, the one with which he (and later she) was born and the one he or she picked as a pseudonym, a type of stage name, and a tradition that is retained today.

Druids

Pages from Stukeley’s Stonehenge showing Stukeley’s impression of a British druid. Source: Stukeley 1740

A revival in Druidism informed the ideas behind the Gorsedd ceremonies performed at eisteddfodau, but it was a form of Druidism that was based on wishful thinking rather than empirical knowledge. Druidic traditions as they developed in the 18th century, although largely fictional, are based on a real historical religious movement that seems to have been widespread in Gaelic-speaking regions during the Iron Age (from c.800BC until the Roman invasion of Wales by around 78AD). This period is sometimes referred to as “Celtic,” although that term is itself full of geographic, chronological and cultural ambiguity, implying an exaggerated degree of homogeneity over vast regions and encompassing significant variation in archaeological data. Both Greek and Roman authors reference the Druids in Europe, particularly in Gaul (now France) and Roman writers later record encounters with Druids on Anglesey. The earliest records that specifically mention Druids are no earlier than the 1st century BC, although as Miranda Green points out, they must have been in existence in some form from the 2nd century BC in order to have been so well established by the time they were being reported. Although some of the historial information about Druids is contradictory, the available texts refer not only to religious belief and ritual (including sacrifice and divination) but also to the curation of knowledge, a culture of oral history and poetry, a judicial role, the application of health cures and a strong affinity with the natural world.

A revival in British interest in Druids and anything Celtic began in the 17th century with John Aubrey (1626-97). Edward Lhuyd, Welsh linguist and antiquarian, produced his Archaeologia Britannica in 1707. He argued that a common origin for language was shared by those who lived in Brittany, Wales, Cornwall and the Gaelic parts of Ireland and Scotland, and the term “Celtic” that he applied to these areas was widely adopted as a term referring to a common Celtic cultural heritage in these regions. The first of the groups based on an idealized view of Druidism was the non-religious Ancient Druid Order established by J.J. Toland in 1717 on the back of a huge wave of interest in all things Druid, and in Wales the antiquarian Reverend Henry Rowlands (1655-1723) argued in his Mona Antiqua Restaurata of 1723 that the megalithic monuments on Anglesey were Druidic temples.

The fascination reached its apex with physician and antiquarian William Stukeley (1687 – 1765). He argued that Druids had come to Britain with Phoenician colonists as priests from Tyre. As Bruce Trigger explains, this tied into his belief in “a relatively pure survival of the primordial monotheism that God had revealed early in human history to the Hebrew patriarchs and hence closely related to Christianity” (Trigger p.111). The tying in of Druidic history with Christianity has been an essential component of the sustainability of the Gorsedd tradition described below, practiced at the Eisteddfod which is often overseen and contributed to by Christian clergy. Stukeley had a Druidic folly in his garden and had himself painted in what he imagined were Druidic style robes. His publications were popular and influential. Druids were not merely respectable in the 18th century; they were fashionable. The reinterpretation of Celtic artefacts and imaginary rituals by artists in the 18th and 19th centuries was often founded on imagined realities, false impressions and incorrect histories, but was hugely influential.

Gorsedd of Bards

Edward Williams, “Iolo Morganwg.” Source: Peoples Collection Wales

Belief in Druidism was essential to many parts of the part of the ceremonial component now a part of the eisteddfod known as the Gorsedd. The word Gorsedd is a Welsh word meaning “throne.” It was employed by former stonemason and bard Edward Williams (bardic name Iolo Morganwg, 1747 – 1826) for the name of his new group and nationalist manifesto, the “Gorsedd of Bards of the Isle of Britain” (Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain, now known as Gorsedd Cymru – the “Gorsedd of Wales”). Williams was brought up in Glamorgan, and knew the bards Lewis Hopkins, Siôn Bradford and Rhys Morgan when young. Although his first language was English, Williams was brought up in Glamorganshire, where he was based for the majority of his life, learned Welsh and was an indefatigable activist on behalf of Welsh interests, advocating for a national library and a folk museum. He travelled in 1771 and went to London in 1773 where he met members of the Society of Gwyneddigion, and attended their meetings. This inspired him to set up an association of bards based on ancient traditions.

His Gorsedd of Bards was the tool that Williams used to promote Welsh culture, particularly that of south Wales, showcasing individuals who furthered the interests of art, music, literature and language. Williams was an interesting, if very divisive character. In order to give his new group a strong historic validity he claimed a personal connection between himself and Iron Age Druids, whose knowledge he claimed had survived and had been passed down through generations in Glamorgan as a secret sect with a series of ceremonies into which he had been initiated by the last surviving Druid. Antiquarian William Stukeley had made Druidism fashionable in the 18th century, and Williams was able to jump on the bandwagon. To substantiate his claims and gain acceptance, he forged ancient manuscripts including a fake Druidic alphabet, which he presented to peers as authentic documents, which were widely accepted by the community of Welsh nationals in London, where he was temporarily living, including the influential Gwyneddigion Society. The account in the I884 Introduction of the Transactions of the Royal National Eisteddfod of Wales, provides a good idea of the sort of fraudulent history invented by Williams:

The records thus furnished, take us back to a time of Prydain ab Aedd Mawr, who is said to have lived about a thousand years before the Christian era, and who established the Gorsedd as an institution to perpetuate the works of the poets and musicians. But the first Eisteddfod, properly so called, appears to have been held at Conway in the year 540, under the authority and control of Maelgwn Gwynedd.* This was followed by a series of meetings held at varying intervals under the auspices of the Welsh Princes, among whom Bleddyn ab Cynfyn and Gruffydd ab Cynan were prominent as patrons and organizers; and the granting of Royal Charters by Edward IV for the holding of an Eisteddfod at Carmarthen in 1451, and by Queen Elizabeth for a similar festival at Caerwys in 1568 [quoted in Wikipedia: Transactions of the Royal National Eisteddfod of Wales, Liverpool, 1884] *Maelgwn Gwynedd (d. c. 547) was King of Gwynedd during the early 6th century.]

It has to be said that Williams was not alone in seeking a largely mythological identity for Wales. There was a precedent in Theophilus Evans and his 1716 book Drych y Prif Oesoedd (Mirror of Past Ages), which re-wrote Welsh history as an epic tale of Welsh descent from a grandson of Noah. It has already been mentioned that in 1717 The Ancient Druid Order had been founded by J.J. Toland and that in 1723 the Reverend Henry Rowlands (1655-1723) published Mona Antiqua Restaurata, which sought and purported to find a Druidic explanation for prehistoric monuments on Anglesey which are now known to have been much earlier. William Stukeley was convinced that the great circles of Stonehenge and Avebury were the work of the Druidic religion.

On 21st June 1792, Midsomer Solstice, Williams built a small stone circle on Primrose Hill in London, with a central stone as a ceremonial focus, and used it to formalize the membership of a number of supporters of Welsh culture into his Gorsedd of Bards. Later in 1792, on September 22nd, this was repeated. The ceremonies that he held in 1792 and afterwards were designed to reward the efforts of those who were making significant contributions to Welsh culture and its sustainability, framing these contributions and successes within a time-honoured Druidic tradition.

In 1795 Edward Williams returned to Glamorgan. At the age of 70 he travelled to the Carmarthen eisteddfod, uninvited, and used a pocket full of pebbles to delineate a Gorsedd circle on the lawn of the Ivy Bush Inn. There he ceremonially inducted a number of individuals to the Gorsedd, providing them with coloured ribbons to indicate their new rank of ovate, bard or Druid. This was the first time that the eisteddfod and the Gorsedd were linked, and the second time a circle had been deployed.

Eventually, of course, Edward Williams was revealed to be a fraud. Even some of his contemporaries were doubtful of his claims, with John Walters (1721-97) referring to his Gorsedd and its historical foundations as “a made dish.” Rather more personally damning, William Williams stated flatly that “no vouches can be produced but the brains of Iolo Morganwg” (the latter being the bardic name of Edward Williams). However it was not until the latter half of the 19th century that academics began to make their voices heard on the subject of the authenticity of the Gorsedd. The very first Celtic professor at Oxford University, John Rhŷs, appointed in 1877, referred to the Gorsedd as “antiquarian humbug, positively injurious to the true interests of the Eisteddfod” (all quoted on the Peoples Collection Wales).

Archdruid Cynan (seated central) in 1956 at Aberdare. Source: Wikipedia

Although doubts were cast on the Gorsedd narrative, with many declaring it to be a fantasy, the false history provided by Edward Williams was not actually addressed until after the 1950s when Albert Evans-Jones “Cynan” (1895-1970), an ordained pastor of the Presbyterian church and tutor in the Extramural Department of the University College, Bangor, became Archdruid. He held the position twice, from 1950 until 1954 and again from 1963 until 1966 and was a considerable innovator, responsible for declaring that the Gorsedd had no connection with ancient Druidism. According to the Welsh Dictionary of Biography:

Endowed with a keen sense of drama and pageant, he realised that the Gorsedd ceremonies were capable of being made attractive to the crowds. He brought order and dignity to the proceedings, and introduced new ceremonies, such as the flower dance. He renounced all the Gorsedd’s former claims to antiquity and links with the Druids, and openly acknowledged that it was the invention of Iolo Morganwg (Edward Williams). He succeeded in gaining many new members, including some academics.”

The Druidic component of the Gorsedd ceremonies is now purely symbolic, but that symbolism still remains an important aspect of the display and ritual. Whilst rejecting the historical links to Druidism, the Archdruid innovated new modern ceremonies that were more inclusive of Christian ideas, marrying them to Celtic symbolism to create a new hybridized approach that retained all the pageantry.

The invention of the Gorsedd of Bards is a truly extraordinary story, not least because it worked. By weaving together a mixture of Druidic history (as it was then understood), Bardic tradition, and spurious historical reimagining supported by faked manuscripts, to lend his ideas credibility, Edward Williams was able to produce a new Druidic-bardic tradition, of which he was himself a key component. As David Lowenthal says

History is customarily made more venerable. those who magnify their past are especially prone to amplifying its age. Relics and records count for more if they antedate rival claims to power, prestige or property; envy of antecedence plays a prime role in lengthening the past (p.336)

Williams did not just massage his data, he faked it, producing a Celtic documentary equivalent of Piltdown Man and like the forger of Piltdown, Williams targeted colleagues and influencers. He used his invented platform of the Gorsedd to relaunch the institution of the eisteddfod as a celebration of Welsh culture. After his death, his son Taliesin worked to continue his father’s legacy.

Stone circles / Cerrig yr orsedd

A prehistoric stone circle in Happy Valley near Aberdovey, mid-west Wales with a friend standing for scale to show how relatively small it is. Dates to the Early Bronze Age.

William Stukeley’s proposal that stone circles like Stonehenge and Avebury were Druidic incorrectly linked what were actually Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age monuments with Druids of the later Iron Age. Even though there are stone circles in Wales, these tend to be small, particularly in north and mid Wales, and go out of use well before the Iron Age. Stone circles were never a feature of the Druidic portfolio. Although subsequent archaeological research placed prehistoric stone circles in a much earlier period, this knowledge was not available at the time. This means that neo-Druidic groups making claims on Stonehenge and other sites are doing so without any basis in the available archaeological data. Edwards very cleverly adopted the stone circle as a useful motif and device for his Gorsedd ceremonies. Given Stukeley’s claims, this must have seemed perfectly reasonable and from 1819 was developed into an important part of the Eisteddfod, with custom-designed Gorsedd circles, cerrig yr orsedd, making very good use of a much older model to meet the Gorsedd’s own needs within the eisteddfod format.

The Gorsedd circle has survived into the modern eisteddfod, and although since 2004 it now uses portable fibreglass “stones”, the circle continues to be a component part of the Eisteddfod. As Archdruid Cynan demonstrated, a belief in Druids is not required to make the stone circle a very effective ceremonial container for some of the Eisteddfod ceremonies, and nor, apparently, is the authenticity of its materials.

xxx

The growth of the eisteddfodau

The eisteddfodau up until the 19th century

There had been a long tradition of eisteddfodau in communities in Wales each adapting the festival to its own requirements at various different scales of endeavour before the idea of provincial, and later national eisteddfodau, were first explored. After the first known eisteddfod of Lord Rhys in 1176, the tradition seems to have survived until the mid-16th century when it went into decline, but began to revive in the early 1700s. John Davies refers to some of the earlier 18th century eisteddfodau as “often drunken and bootless occasions” (p.297), but the value of the event to national interests ensured that in the later 18th century the larger provincial occasions were far more sober and well-structured. Whilst still being enjoyable festivals, pageants and fairs, they focused mainly on Welsh traditions and language, rewarding Welsh cultural output. Welsh music and poetry were major components of these festivals, and so have literature, theatre and scholarship.

As suggested above, in the later 18th century a new interest in Welsh culture had developed both within and beyond Wales and new ways of finding expression of Welsh identity were sought via education, religion and publications. Formal organizations grew up to highlight Welsh cultural distinctiveness and merit and to promote Welsh cultural values, many developing outside Wales to attempt to raise the national profile beyond the country’s borders. Examples are the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion founded in 1751, the Gwyneddigion established in 1771, and the Caradogian Society founded in the 1790s. As these initiatives took off, new means to market Welsh nationality were sought, and the eisteddfod was seized on as a vehicle for promoting these ideas of cultural identity and uniqueness. In September 1789 the Gwyneddigion sponsored the eisteddfod in Bala and might have continued to do so if it had not been for the French Revolutionary Wars (followed by the Napoleonic Wars) when nationalistic activities were strongly discouraged in a climate of fear of sedition and revolution.

In the post-Napoleonic war period enthusiasm for the eisteddfod lingered, and in 1819 the first provincial eisteddfod took place in Carmarthen, when Edward Williams staged his first eisteddfod Gorsedd ceremony. There were signs that the eisteddfod was becoming far more organized and flexible to new ideas. Teifi Williams gives the example of how Edward Williams argued that as well as the cynghanedd, other freer forms of poetic composition should also be welcomed, claiming that this would reflect medieval traditions, but would also open the competition to more bards. At the same time new sources of material were being sought and English songs translated into Welsh became part of the portfolio of Welsh music, absorbed into a narrative of Welsh national musical heritage, not particularly authentic but helping to contribute to the available material.

Rewarding competitions and demonstrations of skill became increasingly important, with a beautifully designed wooden chair, being awarded annually to the winning “Chief Bard,” From 1867 a crown was also awarded annually, and medals began to be designed by well-known silversmiths to highlight the prestige of winning. These medals would merit study in their own right. Cash prizes were also offered to encourage participation and help bards to establish themselves after the events. The competitions have been a particularly good opportunity for Welsh men and an increasing number of women to establish themselves as artists and scholars who might be lauded for their achievements further afield. However, feeding into the format were English contributors and Anglicized Welsh landowners. it was only in the second half of the 20th century that the occasions became more confidently and exclusively Welsh.

The institution of the eisteddfod was given a significant publicity boost in both 1828 and again in 1832 when the events were marked by royal visits. King George IV visited in 1828 at the Denbigh Eisteddfod and in 1832, although poor weather caused the proposed visit of Princess Victoria and her mother to the Beaumaris Eisteddfod to be cancelled, the winners were all taken to Baron Hill, where she was staying, to have their medals presented to them by the future monarch. The winner of the Chair for a poem that year was the Reverend William Williams (bardic name “Caledfryn”) who wrote a poem that is well known even today: The Rothesay Castle (about a ship wrecked off the coast of Anglesey).

Lady Augusta Llanover became an important name in the history of eisteddfodau. In 1834, using the Bardic name Gwenynen Gwent (the bee of Gwent), Lady Llanover won first prize for her essay The Advantages resulting from the Preservation of the Welsh Language and National Costumes of Wales. As well as being a competitor in the 1834 eisteddfod, Lady Llanover (1802-1896) sponsored other eisteddfod competitors, promoted other Welsh traditions, including Welsh wool and costume, and was particularly interested in the Welsh triple harp. As with Edward Williams, English was her first language but she learned Welsh. She was also a founder of the Cymdeithas Cymreigyddion y Fenni (the Abergavenny Welsh Society) founded in 1833 to emulate the Cymmrodorion society. In 1835 as part of the Cymdeithas Cymreigyddion y Fenni she established a new series of ten eisteddfodau in Abergavenny, which lasted until 1853:

By the time we reach the end of this exciting movement with the last of the Abergavenny eisteddfodau in 1853, it’s obvious that the Eisteddfod is on the threshold of a particularly exciting period. By then there were railways the length and breadth of Wales, and this made it possible to bring thousands of people from every part of Wales to the different venues where the eisteddfodau were held. A new era had dawned, and by the middle of the 1850s people were beginning to talk of a National Eisteddfod. The time had come to create one single eisteddfod, yearly, if possible, that would encapsulate Wales’s eisteddfod culture on an annual basis. [Amgueddfa Cymru]

At the same time other local eisteddfodau continued to be organized, each doing things in their own way, so that the tradition continued to grow at all levels.

The provincial eisteddfodau had taken place in an atmosphere of national discontent. From the 1830s the rise of Non-Conformism as an alternative to Anglicanism was widespread, and the working class Chartist movement was increasingly popular. Following the French Revolution there was fear at a state level that protests like those in Newport in 1839, where a crowd of some 20,000 protestors was fired upon by soldiers, and the Rebecca Riots of the 1840s would escalate into something that would threaten national security. It was the Welsh M.P. for Coventry, William Williams, who drew attention to the state of education in Wales, believing that the lack of English teaching in Welsh schools limited employment opportunities. The result was the 1847 Report of the Commissions of Enquiry into the State of Education in Wales, which became referred to as the Blue Books due to the blue binding, and was later referred to as The Treason of the Blue Books after a play of that name was written and performed.

When the report was published it was scathing and sweeping in its findings. Welsh children were poorly educated, poorly taught and had little or no understanding of the English language. They were ignorant, dirty and badly motivated. Welsh women were not just lax in their morals – many of them being late home from chapel meetings! – they were also non-conformist lax. To reinforce the power of the established church and to make English the required mode of teaching and expression in schools is the main thrust of the report. [BBC News]

To make matters worse, Matthew Arnold (1822-1888), an English cultural commentator, poet, Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, literary critic and inspector of schools considered that Welsh would die out and should be allowed to do so. Writing in 1867, Arnold stated that “the sooner the Welsh language disappears as an instrument of the practical, political, social life of Wales, the better for England and the better for Wales itself.” He was supportive of Celtic literature, but thought that in confining itself to Welsh, it failed to engage with mainstream poetic trends in Britain and Europe and would never be fully appreciated outside Wales.

The importance of promoting positive aspects of Welsh life in the face of the Blue Books and other detractors coincided with the increasing popularity of the eisteddfodau, and the establishment of the first National Eisteddfod helped promote Wales as a cultural presence capable of competing on equal terms with the English.

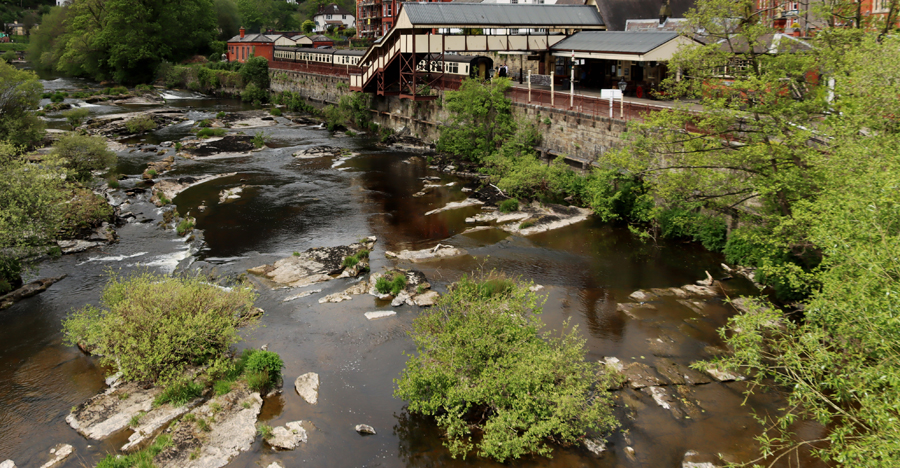

The National Eisteddfod

In 1858 the eisteddfod in Llangollen was a landmark event, the Great Llangollen Eisteddfod (Eisteddfod Fawr Llangollen). In positioning itself as a national eisteddfod, it set the ball rolling for an official annual National Eisteddfod. It was organized by John Williams “Ab Ithel,” one of the adherents of Edward Williams, and made a formal, official inclusion of Gorsedd ceremonies including a stone circle in which to hold them. Michael Freeman notes that the circle for the 1858 event was removed after the event. Llangollen was a good venue because Telford’s improved Holyhead road, now the A5, had opened in 1826 although the railway did not open to passengers until 1862. Llangollen had been a tourist destination since the late 1700s, when Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby were in residence at Plas Newydd, and had continued to rise in popularity. The 1858 eisteddfod was the first time that robes were worn instead of sashes at the Gorsedd, giving it a new feel and a greater Druidic atmosphere. Most entertainingly, an essay was presented by one Thomas Stephens that set about overturning the pseudo-history in which Prince Madog ap Owain Gwynedd had discovered America. Unfortunately the set topic for the eisteddfod was The Discovery of America in the 12th Century by Prince Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd, for which a silver star medal was offered. This had run counter to the type of message of Welsh supremacy that the organizers had been hoping for, and caused no little controversy. Fortunately for the organizers, the poem that won the Chair by John Ceiriog Hughes (Bardic name “Ceiriog”) entitled Myfanwy Fychan of Dinas Brân was an instant and lasting success, creating a model of a virtuous and charming Welsh heroine, and referring to the local castle perched behind Llangollen. In the 1856 and 1858 Eisteddfodau, the song Hen Wlad Nhadau (Land of my Fathers) by father and son team Evan and James James from Pontypridd was sung with such gusto that it was soon adopted as the Welsh National Anthem.

At the 1860 eisteddfod in Denbigh a decision was made to established a national body run by an elected committee to run a National Eisteddfod. The first official National Eisteddfod took place in 1861 in Aberdare. Subsequent eisteddfodau went to Caernarfon, Swansea, Llandudno, Aberystwyth, Chester, Carmarthen, and then Ruthin In 1868. Innovations continued to be made. For example, in 1862, in Caernarfon, a new Social Science category was added, which extended the scope of the Eisteddfod beyond the arts into the realm of the everyday Welsh living. In 1863, although musical compositions had won awards and been performed to enthusiastic reception in the past, the Swansea Eisteddfod marked the first time that a medal was awarded for choral singing, and this became a major aspect of the competition from then on.

From 1895 to 1905 the Archdruid was the Reverend Rowland Williams “Hwfa Mon,” the son of an agricultural labourer who became a carpenter and like so many of the stand-out characters in the Eisteddfod and Gorsedd, had received an education and found a path to an influential position. From being a lay preacher he trained in the Bala Theological College and was ordained as a Congregational Minister in 1851. He became a Bard at the Eisteddfod in Aberffaw in 1849 and rose through the ranks to become the first Crowned bard in Carmarthen in 1867 and Archdruid in 1895. His main claim to fame is his role in fully integrating the Gorsedd with the National Eisteddfod, building on the ideas of Edward Williams, turning the Gorsedd component into a pageant with full ceremonial garb.

From 1910 costs for the National Eisteddfod became the responsibility of the a local committee, to be reimbursed by ticket sales for the main event, as well as for subsidiary events. For the 1908 Llangollen Eisteddfod, for example, as well as turnstile takings, an Arts Exhibition, with items on loan from London and from local collectors, was ticketed separately.

In 1876 the first “empty chair” had been awarded at Wrexham, when the winning submission had died and the Chair was awarded posthumously to Thomas Jones (Taliesin o Eifion). This was echoed in 1917 when the Chair was again empty. The Chair had been awarded to Ellis Humphrey Evans “Hedd Wyn” (Blessed Peace) but Private Evans had died in the trenches whilst serving with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. The Chair was covered with a black sheet to indicate mourning.

xxx

The example of the 1908 Llangollen Eisteddfod

The pavilion of the 1908 National Eisteddfod. Source: People’s Collection Wales (Llangollen Museum Object Reference 2005_20_42)

Using the 1908 Eisteddfod as an example, gleaned mainly from contemporary newspaper reports, holding the Eisteddfod was an important event for the town. It is referred to as the “Ceiriog Memorial Eisteddfod” (after the bardic name, Ceiriog, of the winner of the 1858 Llangollen Chair), the “Llangollen Jubilee Eisteddfod” or the “Royal National Eisteddfod.” It marked the 50th year anniversary of the Great Llangollen Eisteddfod of 1858, when the Chair was won by Ceiriog for Myfanwy Fychan of Dinas Bran. Ceiriog was important to Llangollen, and is sometimes referred to in Welsh newspapers as the Burns of Wales, reflecting Welsh hopes to produce a poet who would be recognized outside Wales.

The organizing committee clearly felt under pressure as a comparatively small venue to put on a show just as impressive as those of its larger predecessors, and took the fact that it was the Jubilee year very seriously. Local dignitaries were recruited to form a committee, including landowners, clergy, and civic officials, and and the entire community was involved in delivering the fully functional enterprise. A 60ft (18.3m) stone circle was decided upon and built in 1907 for the proclamation ceremony (about which more below), and the design for the pavilion, after much discussion, was agreed. It was made of wood with a corrugated iron roof, which was designed to be easy to dismantle after the event, but which actually managed to withstand the dreadful wind and rain in the Eisteddfod week at Llangollen. It slighting was supplied by one T.C. Davies who used acetylene gas that cost the committee one third of what any other form of lighting would have cost them. Usually the pavilion was the covered stage for the main events, including competitions and the awarding of prizes, and the circle was the focus of the Druid-inspired Gorsedd ceremonies, but because of the rain some of the Gorsedd ceremonies had to be conducted in the pavilion.

Details of the Week’s programme from The Welsh Coast Pioneer and Review for North Cambria 3rd sept 1908

As well as ceremonial and competition considerations there were the logistical arrangements required for a huge influx of visitors. Extra trains were put on for visitors from the wider area including North and South Wales, Cheshire, Lancashire, Yorkshire and Staffordshire, and the railway station took measures to cope with the volume of passengers that they would have to process. Extra police were brought in to help direct crowds and to cope with any wayward behaviour, and the Post Office arranged for extra mail handling requirements. Even the Parish Church put on special services for the visitors, with a service delivered by the Lord Bishop of Ottawa, visiting from Canada.

After the opening ceremony in the Gorsedd circle, the Art Exhibition was opened by The Countess of Grosvenor on Friday August 28th with an opening speech by Sir Theodore Martin. As well as two chairs once belonging to Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby, the famous owners of Plas Newydd up until 1831, there were items relevant to the 1858 Eisteddfod, including the wreath won by Ceiriog and the original manuscript of his winning Myfanwy Fychan of Dinas Bran. Ab Ithel’s gold tiara and satin robe, and the hirlas horn were all present too. Local property owners also supplied items of interest. Of more universal interest were paintings by JMW Turner and David Cox, supplied by the South Kensington Museum. There was also a demonstration of weaving, the Mile End Mills having loaned a loom, whilst other local companies supplied an oil engine and a card setting machine. It was apparently visited by hundreds of visitors. The art exhibition was ticketed separately. It accompanied a set of papers delivered later in the proceedings on the subject of developing art in Wales. The Cardiff Times (12th September 1908) commented that it was suggested that until national or public art galleries were established to provide public access to art within the Principality, “[a]rt in Wales is in the future and not the present.” Although ticketed separately, the exhibition was apparently a great success.

Given that the competition for the Chair and Crown were both for Welsh-language verse, the winners were almost inevitably Welsh. The Chair (shown in a photograph further up the page) was awarded to the the person deemed to be the prifardd (the main or chief bard) for an awdl a long-form poem written in strict metre according to specific rules around alliteration, assonance, and internal rhyme (cynghanedd), which was still expected to have emotional content. In 1908 it was awarded to ordained preacher John James Williams (“JJ”) for his poem on the fixed theme for the awdl competition, “Ceiriog.” John Ceiriog Hughes had been the winner of the chair in the 1858 Llangollen Eisteddfod, and his two daughters were on the platform during the ceremony and participated in the investiture. The Crown was awarded to Hugh Emyr Davies (“Emyr”), a Welsh Presbyterian minister for his poem, awarded for free metre (pryddest) on the theme of Owain Glyndwr. Both ceremonies were performed within the pavilion. The announcement of the winner of the Crown was preceded by the bards appearing in their robes and paraphernalia, and forming an arc behind the Archdruid. Two of the three judges (the other not in attendance) stepped forward and the unanimous judgment was given. The poet “Emyr” knelt before local dignitary Mrs Bulkeley Owen for the crowing, after which he was accepted into the fraternity with the recital of poetry and a song.

A crown made in arts and crafts / art nouveau style that was given to the winner of the free verse competition at the National Eisteddfod of Wales. Made of silver, green enamel and velvet. Produced in 1908 by Philip and Thomas Vaughton. Source: Titus Omega via Art Nouveau Style.

Other competitions taking place throughout the week included prizes for literature; music (vocal, choral and instrumental as well as compositions); arts, crafts and science; sculpture and modelling; architecture; photography; designing and decorating; and wood and stone carving. There were also prizes for different age groups, so that children could be included. In between events there were many speeches, some by local worthies, others by more widely known individuals. On one of the days both David Lloyd George (Chancellor under Herbert Henry Asquith) and Winston Churchill (President of the Board of Trade), travelling together, gave speeches. The speech by Lloyd George was a somewhat romantic and hyperbolic view of Welsh history as derived from the mountains and valleys themselves and spoke of his pride in Welsh progress (described by one columnist for the Aberystwyth Observer as “a mere string of platitudes interspersed with florid compliments to his own country and people”); that of Winston Churchill referred to Wales as a “sea of song” and he hoped that that song would endure and preserve what was best in the Welsh national character and faith. A more interesting speech was by Mr Llywelyn William MP who “transgressed the time honoured rule which bans politics from the Gorsedd circle and the Eisteddfod platform by declaring he looked forward to seeing a national Parliament, like that over which Llywelyn the Great presided,” which was followed by applause [The Aberystwyth Observer, 10th September 1908]. The Bishop of St Asaph was invited to speak not because of his episcopal position but due to his eminence as a Welshman. The speech by Sir Merchant Williams, which was reported in several newspapers, is quoted further below.

Off-stage, some of the more sensitive discussions were held, such as the important consideration of the Archdruid’s Reform Bill, (which was referred back to a committee for consideration due to concerns that could not be resolved) and the problems of the Breton Gorsedd delegation, which resulted in the statement that the British Gorsedd would never interfere with political or sectarian questions. The event was also dotted with a number of concerts, receptions and banquets, including an event to celebrate the presence of some 50 delegates from Patagonia. Importantly, it was also decided which town would win the competition to host the National Eisteddfod in two years time (Colwyn Bay was selected to follow London’s Albert Hall Eisteddfod of 1909).

Although the winners of the two main Welsh-language poetry prizes were both Welsh, no Eisteddfod was a purely Welsh affair. Part of its purpose was to demonstrate that the Welsh could compete on equal terms with the English in music, and this meant that English competitors, as well as some European ones, were a big part of the Eisteddfod well into the 20th century. Indeed, five Eisteddfodau were also held in England – in Chester (1866), Liverpool (1900 and again in 1929), London (1909, following the Llangollen Eisteddfod) and Birkenhead (1917), which one of the newspapers interpreted as a successful transmission of Welsh traditions across the border.

The last day featured a brass band contest, after which the end of the Eisteddfod was marked by a splendid display at Plas Newydd to celebrate the success of the event. The Llangollen Advertiser provides a vivid description:

The splendidly complete arrangements made Mr. Robertson for the illumination of the grounds of Plas Newydd, on Wednesday evening during Eisteddfod week, were in every way admirable. A Manchester contemporay, in the course of an elaborate description of the effect, says; “The outline of every flower-bed was picked out with coloured fairy lamps. In among the geraniums they lay in almost dazzling pro fusion—white, amber, and rose—and some there Were of an icy, greenish blue, like giant glow- worms in the grass. Chinese lanterns, too, were hanging in lines between the distant trees, and the water tower, black and white like the house, though half leaf-buried, had near its summit a huge star of gleaming. All Llangollen, little and big, bad mounted the hill to see the sight, And were now peering over the garden hedge from the neighbouring lane, either standing on tiptoe or seated at ease on a paternal shoulder. The mosaic of ground lights cast a flush on the long line of watchers’ facts and turned into maidenhair the canopy of birch leaves overhead. It picked out, too, the grotesque outlines of poodle-clipped yew trees, unvenerable though so old, and by its many-tinted reflex made medley of the stained-glass windows of Plas Newydd.” [Llangollen Advertiser, 11th September 1908]

Olga Harte winner of the under-16 violin solo. Source: Evening Express, September 3rd 1908

The Pembroke County Guardian and Cardigan Reporter was pleased to note, on 11th September 1908, that even though there were big crowds with over 7000 people a day through the turnstiles, there had not been a single reported case of drunkenness or disorderly conduct, and that the police had experienced no difficulties managing the revellers. This is surprising, as not only were people pouring in from the immediate area, but special trains had been put on to carry people from much further afield. This was quite unlike the “often drunken and bootless” occasions of earlier eisteddfodau reported by John Davies.

The Cambrian News and Merionethshire Standard on 11th September reported that 34,626 visitors had been recorded through the turnstiles. The newspapers reported that the finances after the event were healthy. The Llangollen Advertiser on 11th September commented that “the financial success of the National Eisteddfod id virtually assured – something like £500 being required to meet all claims, something over £950.00 having been taken yesterday.”

Overall, although the standard of singing was thought to be inferior, possibly because some of the most prestigious competitors were unable to attend due to bad weather, and the weather itself spoiled some of the Gorsedd ceremonies, the media deemed that the Eisteddfod as a whole was a great success.

xxx

Gorsedd circles and their role in the eisteddfodau

The Gorsedd circle was developed as a ceremonial space, using a millennia-old design to create a marketable image of a modern Welsh identity with roots that were positioned as deriving from Celtic traditions. Edward Williams, influenced by the ideas of William Stukeley and others incorrectly associated stone circles with Druids, worked back from a desired state of Welsh identity to provide his nation with time depth and historical integrity towards making that desired time-honoured identity a reality.

The Proclamation, described above, took place a year and a day in advance of the event, and this now takes the form of a procession to the circle where the next eisteddfod is announced. The National Eisteddfod celebrations, which are not exclusively Gorsedd, shift between the circle, the pavilion and, in subsidiary temporary structures in the the field in which the entire event takes place, (Y Maes). The first Gorsedd ceremony held by Edward Williams on Primrose Hill took place in a stone circle, and for his impromptu arrival at the 1819 eisteddfod he carried pockets full of pebbles. After then most circles were temporary, and sometimes none were built at all. The first permanent stone circle was built in 1897 at the Newport (Gwent) National Eisteddfod and they have been a much valued component of most of the annual celebrations in Wales ever since. Most were permanent but the five held in England were all apparently temporary.

Over the course of two decades Michael Freeman (former curator of the Amgueddfa Ceredigion / Ceredigion Museum) has carried out a comprehensive research programme, effectively an archaeological survey. This research has found that of around 90 circles originally built around 75 survive. Most of these are not shown on the Ordnance Survey maps and until the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW) recorded Michael Freeman’s research, complete with grid reference and NPRN (a unique RCAHMW identifier), they were not listed as heritage monuments. They have been divided into four categories, which enable the trends and differences in Gorsedd circle building to be compared. For those interested in knowing more about the permanent Gorsedd circles, see Michael Freeman’s web pages dedicated to the subject on his Early Tourists in Wales website. It makes for fascinating reading.

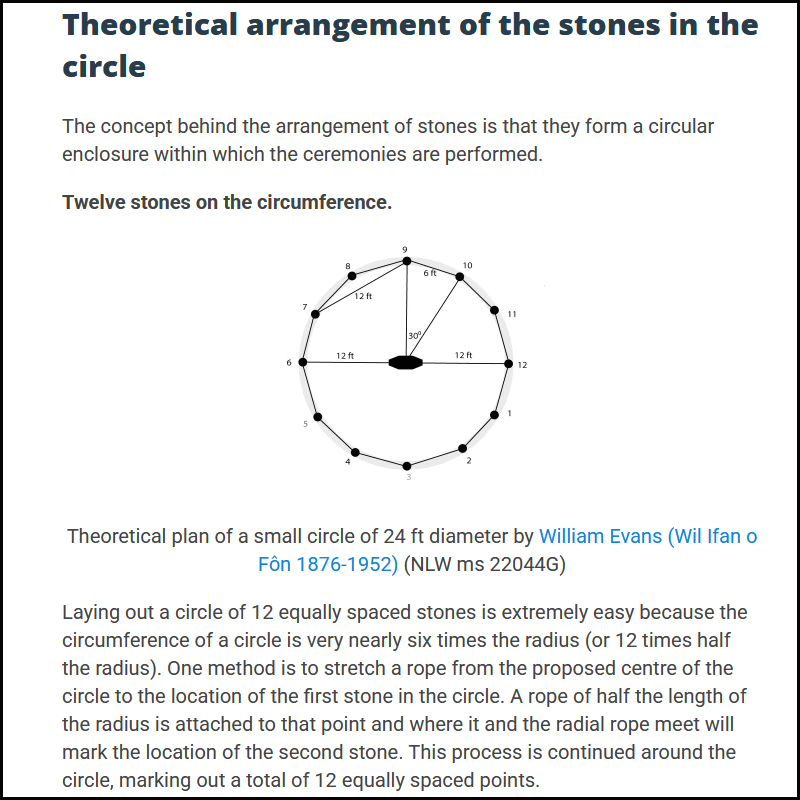

Michael Freeman’s research has shown that the most common circles consist of a single circuit of 11 or 12 stones, a central large stone, the Maen Llong (Logan Stone), which acts as a focal point and what was a Druidic altar but since Archdruid Dyfed’s tenure is now secular. This basic layout could be supplemented by two or more outliers or inliers which either reflected points where the sun would rise at certain times of the year, or alternatively the symbol of the Gorsedd, a three-stroke symbol known as the anwen or Y Nod Cyfrin. Interestingly, Michael Freeman’s work has found that the location of the circle was usually one of convenience and had little to do with a good position in terms of solar or astronomical observance. This would not usually have been the case in the Early Bronze Age, when most were built and when sites were often located where they provided views into the distance, where large portions of the skies could be observed.

Incorporated into the timetable of the National Eisteddfod, such as the one that took place in the 1858 and 1908 Eisteddfodau at Llangollen, a number of ceremonies took place. First is the Proclamation ceremony that gives a year’s notice of the event, and which involves a ceremonial procession to the circle accompanied by music, school children and other community groups. Some of the ceremonies that take place during the Eisteddfod are for granting awards to the competition winners and others are for rewarding the achievements of those who are to be formally admitted to the membership of the Gorsedd, either by completing exams or by having made some significant contribution to Welsh culture or language.

Just as in the 1819 ceremony, there are three classes of Gorsedd membership, each represented by a different colour: ovates (green), bards (blue) and Druids (white). When Edward Williams began the Gorsedd ceremonies he used ribbons, but these became sashes and eventually became robes. These categories used to form a tripartite hierarchy, but are now considered to be on equal footing. There is, however, an elected head of the Gorsedd known as the Archdderwydd (Archdruid) whose robe is gold and has tenure for three years. The form of the ceremonies is designed to reference Druid iconography, and includes rituals supported by ritual objects and accompanied by prayers and chanting. The key material components of the Gorsedd at a national Eisteddfod, apart from the stone circle itself, are the corn hirlais (horn of plenty), the Grand Gorsedd Sword (sheathed at the end of the ceremony to symbolize peace), the Y Corn Gwlad trumpet, an official banner introduced in 1896, and roles and regalia that were introduced at different times, including the crown, breast-plate and sceptre that are often prominent in photographs. The symbol known as the mystic mark, consisting of three converging slender triangles, was known as the anwen, Nôd Cyfrin or Nôd Pelydr Goleuni (mark of shafts of light) was not much used during the life of Edward Williams, but was employed by his son, and became a popular icon of National Eisteddfodau. Robes and insignia were introduced to replace sashes in the 1858 Llangollen National Eisteddfod.

Interestingly, Gorsedd sites were never objects of pilgrimage, even when still associated in Gorsedd lore with ancient Druidism. They may hold local importance, and are sometimes tourist attractions, but even before a more formal synthesis with Christian ideas and rituals, they were never seen as Druid temples in their own right. Nor are they seen as Christian places of worship.

The point has already been made that in the context of an eisteddfod, local or national, the cerrig yr orsydd are an artifice in the sense that they were never associated with the medieval tradition of the eisteddfod. The stone circle was chosen as an emblem decided to reference prehistoric monuments and this too is an artifice because the Early Bronze Age circles have nothing to do with the later Druidic sects. Although they have only recently been acknowledged as heritage in their own right, the Gorsedd circles are fixed reminders that an Eisteddfod has taken place there and that these events represent the value of Welsh cultural output, stamping a sense of modern Welsh identity on the landscape. It was a brilliant idea, but a shame that it required the dragging in of ancient Druidism to give it momentum. Since 2004 the cerrig yr orsedd are not actually made of stone and are not permanent. Fibreglass look-alikes are used instead, which must greatly simplify the logistics, and saves much of the hand-wringing that has taken place when permanent circles are sometimes found to be in places that interrupt modern development plans.

Gorsedd circles are a long-term material emblem and reminder of past eisteddfodau, collectively representing a recognizable identity associated with specific ideas, values and cultural beliefs. For every community in which a Gorsedd circle still stands, it carries social and cultural significance that is both locally grounded and an integral part of a larger tradition into which those individual communities are linked by having played their part in a grand Welsh tradition.

xxx

The Plas Newydd Gorsedd Circle

1908 Gorsedd circle. Plas Newydd is behind it with Mr George Robertson’s wing before it was demolished, and Castell Dinas Bran at the top of the hill behind the house. Peoples Collection Wales (Object Ref 2001_6_47, Llangollen Museum)

The Plas Newydd stone circle is located in a small field just beyond the remarkable house of Plas Newydd, overlooked by topiary and surrounded by a driveway that today serves as parking for visitors. It has been recently recorded by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales as NPRN 800631.

The Gorsedd stone circle itself was a community effort, and at the centre of decisions about how the Proclamation ceremony, which would take a year in advance of the main event, would be managed and experienced. At a planning meeting of the organizing committee it was decided to ask Mr George H. Robertson who owned Plas Newydd for the field next to the house, so that a procession could be organized from the town up the hill to the circle. Mr Robertson, a Liverpool cotton trader, was one in a line of owners of the Plas Newydd cottage, all of whom maintained the legacy of Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby as well as making modifications of their own. He contributed a new wing to the cottage that can be seen in the above photograph (demolished in the 1960s) and probably added new features to the original building, whilst maintaining what was already in situ. He was also responsible for the yew tree garden and the topiary. His gift of the land for the Gorsedd circle, and his decision to make the circle a permanent feature, has added to the already unique personality of Plas Newydd.

The central stone in the middle of the Gorsedd circle, on top of which many of the ceremonies were performed

The Llangollen circle is spacious, with a diameter of 60ft (18.3m), with twelve evenly spaced large rocks around the circumference, averaging 2 tons each, as well as the 5-ton 8ft (2.4m) long monster at its centre, the maen llong (Logan stone). There are also three outliers. There are different explanations for what outliers, which occur at other sites too, may represent. One newspaper, the Chester Courant and Advertiser for North Wales, describes the Llangollen outliers as representing sunrise, midday and sunset, but more generally they may equally represent the Y Nod Cyfrin (or anwen), used by Edward Williams to represent love, justice and truth. Judging from Michael Freeman’s survey, at 60ft (18.3m) it was smaller than most of the surviving circles (which are between 75-80ft / 23-25m), but it was exactly twice the size of the reported diameter for the 1858 Llangollen circle. Before 1900 most were fairly small, portable stones, but in the early 1900s the stone circles became larger and enabled more elaborate ceremonies.

Michael Freeman’s diagram of the layout of the Llangollen circle with its central Maen Llong and three outliers, type 2d. Source: Early Tourists in Wales

The circle at Plas Newydd with the outliers highlighted in red.

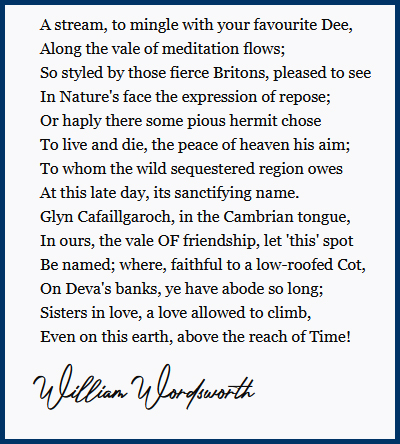

Although Stonehenge with its seriously modified uprights and lintels is impressive and influential, most prehistoric stone circles were made of unmodified stones that were chosen for their individual properties before being raised into position, and these have a quite different character from anything as thoroughly transformed as Stonehenge. The Llangollen Eisteddfod organizers chose the more natural prehistoric circle for their model, as required by the Gorsedd guidelines. By 1907 they had the technology to batter rocks into a particular form, but they chose to use unaltered stones from local Pengwern Hall. They deployed vast, natural rocks into an unnatural symmetrical form, and in doing so they effectively bridged between nature and design to create a contained but permeable space in a way that is spectacularly effective. They It has more in common with the prehistoric stone circles of Cumbria than anything like Stonehenge or Avebury.

Each stone circle, whether prehistoric or modern, big or small, has its own particular personality, and the one at Plas Newydd is impressive both in its scale and in the individual rocks chosen to give it a real presence in the landscape. The spacing of the stones provide a dual sense of delineation and permeability. It is easy to see how it can be used as a zone of inclusion-exclusion when the occasion demands, but at the same time it is easy to move through and around, making it a monumental but subtle component of the Plas Newydd gardens that does not block access. By using products of the natural world to define the space there is the sense that the landscape itself, the hills and valley have been incorporated into the experience, with Castell Dinas Bran above, itself looking like an extension of the landscape. This is reflected in the Pembroke County Guardian and Cardigan Reporter on 11th September 1908 which commented that the stones were “all massive natural bounders collected from the surrounding mountain sides and so deeply embedded in the soil that they appear to have been planted not by the hand of man but forces of nature.”

In 1907 the new Llangollen Gorsedd circle was erected in what was named the Heritage Field at Plas Newydd and the 1908 Llangollen Royal “Ceiriog” Eisteddfod was proclaimed in June 1907 at a ceremony in the newly built stone circle. The Llangollen Advertiser described the procession at 1pm:

Archdruid Dyfed (Evan Rees). Source: Wikipedia

Proclamation Ceremony of the Welsh National Eisteddfod of 1908, which is to be held at Llangollen next Autumn, took place yesterday (Thursday), upon the beautiful enclosure at Plas Newydd, kindly placed at the disposal of the organisers by Mr. G.H., Robertson, the owner of the historic residence. A procession was formed in the Smithfield at one o’clock, and consisted of contingents of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, Denbighshire Yeomanry, Worcestershire Militia, Denbighshire Constabulary, Llangollen Fire Brigade, Friendly Societies, Llangollen Urban Council, Tradesmen’s Association, Cymrodorion Society, Lord Lieutenants and representatives of the various public administrative bodies in Denbighshire and the adjoining counties, the Mayors of Aberystwyth, Wrexham, Shrewsbury, Ruthin. Oswestry and Llanfyllin attending in their official robes. There was a very large gathering of Justices of the Peace and the representatives of the Celtic Society deputised to attend were Lord Castletown of Upper Ossory, and Sir William Preece, F.R S., Chairman of the London Committee. Mr. and Mrs. Darley were the representatives of the Dublin Cymric Society and Sir Marchant Williams represented the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion.

After marching through the principal streets of the town the procession entered the beautiful enclosure selected for the interesting ceremony, and a more appropriate site could not possibly have been selected. The beautiful foliage of the surrounding trees in the full glory of summer foliage, the distant view of Castell Dinas Bran, “the most proudly perched ruin” in Britain, the excellently ordered gardens which surround Mr. Robertson’s romantic residence, were among the outstanding features in a picture of singular beauty and interest. After the opening of the Gorsedd by the Archdruid Dyfed; the Rev. Edwards (Gwynydd) offered the Gorsedd prayer; several addresses were delivered. [Llangollen Advertiser, 21st June 1907]

The North Wales Express provided a slightly different version version:

The Llangollen National Eisteddfod of 1908 was proclaimed on Thursday in a storm of wind and rain by the Archdruid Dyfed, and a large concourse of bards and ovates. The procession was very imposing. A choir of school children, drawn from all the elementary and the intermediate school, under the leadership of Mr W. Percerdd Williams, were assembled ready at the Gorsedd portals, and as the Archdruid (Dyfed) and his brilliantly-robed retinue entered they were greeted by a volume of sweet voices, rendering a selection of Welsh airs. The “Corn Hirlais” was gracefully presented by Miss Barbara Robertson, Plas Newydd. and Miss Nanson, while the “Aberthged” was presented as Miss Williams, daughter of the guest Ab Ithel, accompanied by Miss Hughes, Glanynys. A long list of candidates for honorary degrees were invested by the Archdruid, and the usual in memoriam addresses were delivered . . . Mr J. Herbert Roberts, M.P., was admitted a member of the Gorsedd under the designation “Gwenalit.” [North Wales Express, 28th June 1907]

In the 1908 Eisteddfod, opening events were shared between the Gorsedd circle and the pavilion. Most of the newspaper accounts mention that on all but the last day there was pouring rain throughout most of the Gorsedd ceremonies which, as one news paper put it “it being impossible, in the midst of driving showers to secure the attention of the crowd surrounding the Gorsedd circle” [Llangollen Advertiser 11th September 1908]. It was stated in the newspapers that this was one of the wettest Eisteddfodau that anyone could recall, but there was still a terrific attendance. Even though some of the Gorsedd proceedings had to be held in the pavilion instead of the circle, all were overseen by Archdruid Evan Rees “Dyfed” who had tenure from 1905-1923. Following on from his landmark predecessor the Congregational minister Rowland Williams “Hwfa Môn”, Archdruid Dyfed wanted to introduced various innovations. His outlook must have been quite interesting as he had participated in the 1893 International Eisteddfod at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago Illinois, where he won the Bardic chair with an awdl on Jesus of Nazareth.

At the Gorsedd circle the first ceremony was the opening of the event. Because the event is carried out within full sight of the wider community and visitors it absorbs much of their energy, because the success of the ceremony and pageant are dependent on the crowd. Part of the ceremony is a call out and response between the Archdruid and the crowd, a call for peace, with a single voice raising the call, and a vast crowd, sometimes of thousands, responding in the affirmative.

However, the Pembroke County Guardian on the 11th September believed that the Thursday’s Gorsedd procession “more than made amends for any shortcomings in Tuesday’s gathering.” Having made a tour of the whole town, the procession gathered at the circle where the ceremony included a contingent of Patagonians, the two daughters of Ceiriog, and a Welsh national from the Transvaal, all of whom witnessed an honorary Gorsedd degree being awarded to Lady st David (given the bardic name “Goleuni Dyfed” – the light of Pemborkeshire) due to her paper delivered during the Eisteddfod on the subject of the establishment of village societies for the encouragement of art and music.

Archdruid Dyfed at the 1908 Llangollen Eisteddfod. Source: Evening Express

Some of the costs and takings of the Eisteddfod were reported in local newspapers, but there is nothing mentioned about the cost of the circle itself. It may be that as the stones were provided by the owner of Pengwern Hall, and were delivered using Pengwern transport, the charges may have been absorbed by the estate as a charitable gesture, in the same spirit in which the land where it sits was provided by the owner of Plas Newydd.

Today the meaning of the Gorsedd circle is largely lost on visitors from outside Llangollen. I have found no signage to explain its significance, and there are no objects to commemorate the event in the museum. I daresay people come up with their own interpretations, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it would be nice to have some information available to those who might welcome it. It does give people the freedom to interact with the circle on their own terms.

In 1958, half a century after the 1858 eisteddfod, the Bard’s Memorial was built on the site of previous Plas Newydd owner General Yorke’s peacock house. This is a commemorative structure, referring to the past but not part of it. The 1907 circle, quite apart from being so enjoyable, has the added gravitas of having been an integral part of the 1908 National Eisteddfod and remains a very attractive symbol of Welsh determination in the 19th and early 20th centuries to promote its cultural heritage.

xxx

The question of authenticity

Edward Williams was desperate to connect modern Wales with its more magnificent, albeit partly imagined cultural past. His Gorsedd ceremonies have become an integral part of the National Eisteddfod. The Gorsedd tradition invented by Williams is based on an entirely inauthentic narrative to promote a particular agenda substantiated by fraudulent documentation. As Lowenthal says, “The rectified past aims to be seen as the true original . . we alter the past to become part of it as well as to make it our own” (p.328-31) and this is what Williams was attempting. In many ways his aims were admirable in trying to recover and reinforce a sense of Welsh national identity, but it is difficult to ignore his methods.

Manuscript showing the Gorsedd robes and headgear designed by T.H.Thomas, c.1895. Source: Peoples Collection Wales

Does it matter that in order to build up a sense of Welsh cultural self-worth and identity, Williams lied and forged documents? This question was asked throughout the later 19th and early 20th centuries, and was addressed at some length in the local media at the time of the 1907 Proclamation ceremony In Llangollen. On Friday 21st June 1907 a column in the Llangollen Advertiser commented as follows:

In a sense the Proclamation Ceremony is the ornamental side of the Eisteddfod but it is something more than this. By some it is regarded as a purely archaic survival that might very well be dispensed with or at any rate very considerably reformed” and goes on to suggest that it is very much an important part of the Eisteddfod. But even this anonymous supporter of the Gorsedd ceremony highlights the great difficulties of determining historical accuracy: “When one attempts to penetrate into the deeper depths of Bardic Law, and the historical facts and legends upon which it is based, the result is somewhat perplexing and the same differences of opinion and variation of views are manifest in this as in other matters where points of historical accuracy have to be decided and deductions drawn therefrom. [Llangollen Advertiser, 21st June 1907]

At the same time, Sir Marchant Williams gave a speech at the Eisteddfod Proclamation Ceremony that was an impassioned declaration in favour of the Edward Williams version of reality:

An address was delivered by Sir Merchant Williams, who referred to the contempt- with which some Welshmen viewed the proceedings of the Gorsedd, and to the assertion of Professor Morris Jones, of Bangor, that the antiquity of the Gorsedd and its authority were a myth. He said that inquiries by scientific archaeologists proved conclusively that the Gorsedd was flourishing before a single stone was laid of the oldest college in Oxford or Cambridge, and he predicted that the Gorsedd would be flourishing when the colleges- of Oxford and Cambridge were in ruins. Whether it was old in its origin or recent, he loved and cherished it for the simple reason – that it was unique; it characterised and separated the Welsh nation from all other nations under the sun, and re- served to live on that account solely. [North Wales Express, 28th June 1907]

Plaque to Edward Williams (bardic name Iolo Morganwg) on Primrose Hill, London. Source: London Remembers

Because Archdruid Cynan addressed the issue from the 1950s, renouncing all Gorsedd claims to antiquity Druidic connections, and openly acknowledging that it was based on fraudulent claims and manuscripts, there is much less controversy in the ceremonies of the Eisteddfod. Still, the Druidic robes and objects, however artificial, continue to be part of the pageantry. Lowenthal believes that many actually enjoy the contrived aspects of modern ceremonial clothing and objects, because they are specially made and designed, a product of the present, something consistent with how people live their lives today, but with a nod of respect to the past, a bit like re-enactment.

Lovely Welsh poet Dannie Abse has rejected the validity of criticism of Edward Williams on the grounds that he was a great scholar and poet, but many of the residents of Primrose Hill seriously resented the new plaque that venerated him on the grounds that he was a blatant fraudster. In fairness to the plaque, it does not praise Williams, saying simply “This is the site of the first meeting of the Gorsedd of the Bards of the Isle of Britain 22.6.179 / Yma y cyfarfu Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain gyntaf.”

It cannot be doubted that Williams was an important contributor to the promotion of Welsh culture and the success of the National Eisteddfod. I suppose that it comes down to whether you believe that the end justifies the means.

xxx

Final Comments

When I set out to write, just for a change, a nice short piece as part 4 of my series on Plas Newydd, departing for the moment from talking about the house itself, and looking instead at the stone circle in its grounds, I had no idea what a complicated story would emerge. The post turned into yet another exploration of a subject from the roots up, and was infinitely longer than I anticipated when I started it, but it was a fascinating learning curve.

Llangollen Advertiser 1908. Source: National Library of Wales

The concept of the eisteddfod goes back far beyond the introduction in the 18th century of the Gorsedd component, but the two are now, at least at the level of National Eisteddfod, inseparable, and this linkage is what is captured by the stone circles at Plas Newydd and elsewhere. By rooting the Gorsedd in ideas of antiquity and introducing it to the Eisteddford, Edward Williams found a way of validating and legitimizing Welsh culture and its artistic output. The new interest in promoting Welsh identity in the 18th century began in London with Welsh nationals living in England, and for decades continued to be influenced by Anglicised Welsh landowners, and by English participants. By competing against English artists, the Welsh were able to prove their own abilities, but this involved a compromise in which an essentially Welsh festival became bi-national. In 1909, the year following Llangollen, the National Eisteddfod went to London where, according to The Cardiff Times on 2nd January 1909, it had resulted in the “energising of national life among London Welshmen” and had “secured the hearty co-operation of every section of the Cymric colony in the Metropolis.”

One of the interesting aspects of the 18th and 19th century Eisteddfodau is that when looked at in more detail, this is often “history from below.” The involvement of both working class and educated people to compete in Welsh language events gave it a broad social spectrum, albeit exclusively male for some time. Some of those competing were people who worked with their hands, like miners and carpenters, and although there were also clergy in their number, many of these had equally humble beginnings.

Today the National Eisteddfod continues to be held annually in the first week of August every year, alternating between North Wales and South Wales and since 1950 has become a Welsh language experience and all signage, speeches and competitions have been in Welsh. To help it to survive, the Eisteddfod Act of 1959 permitted local authorities to provide financial contributions to the event. This year (2025) it is to be held at the Welsh-English borders near Wrexham from 2nd to 9th August at Isycoed near Holt. It remains a competition with prizes offered in poetry, prose, music, dance, theatre, social science and Welsh language and is a busy social event with artisan stalls and food vendors. It will take a pragmatic view on the weather for the Gorsedd ceremonies, as this page from the National Eisteddfod website explains:

When the weather is fine, the ceremonies to welcome new Gorsedd members are held in Cylch yr Orsedd. If the weather is poor, they’re held in the Pavilion.

The Archdruid leads the Gorsedd ceremonies in the Cylch and on the Pavilion stage. New members are welcomed on Monday and Friday mornings at 10:00, and the Crowning, Prose Medal and Chairing ceremonies are held in the Pavilion at 16:00 on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, respectively.

The Plas Newydd Gorsedd Circle has a fascinating story, both as part of the Gorsedd heritage and as a part of Llangollen’s community history. It is attractive in its own right, and a superb add-on to the unique and fabulous house of Plas Newydd with its lovely stream-side dell. It has a great personality all of its own, and it is nice to see it being used on an informal basis. People rest against the stones in sun or shade, some with picnics, some simply relaxing and enjoying their surroundings with its views to the house, the topiary and beyond to Dinas Bran. In spring the circle is flanked by purple crocuses. It is a really lovely piece of heritage.

1908 Llangollen Pennillion singing at the Gorsedd on top of the Maen Llong. Source: Peoples Collection Wales (Llangollen Museum, Object Reference 2002_32_28)

xxx

Visiting Details

Visiting details are in Part 1, but if you only want to visit the gardens and the Gorsedd circle, these are free of charge. The Plas Newydd website is at https://www.denbighshire.gov.uk/en/leisure-and-tourism/museums-and-historic-houses/plas-newydd-llangollen.aspx. What3Words address for the site is ///occurs.stowing.neck. Parking at the site is free, but limited. There is parking in Llangollen, although at the height of the season, parking at the International Eisteddfod stadium is a good idea. The short walk back into town along the canal is very enjoyable and a great way to experience a small sample of Llangollen’s canal walks.

The Eisteddfod advert for the Parish Church services in the Llangollen Advertiser, featuring the Lord Bishop of Ottawa

Sources

Books and Papers

Arnold, Matthew 1867. On the Study of Celtic Literature. London

Arnold, Matthew 1867. On the Study of Celtic Literature. London

https://archive.org/details/onstudyofceltic00arno/page/n5/mode/2up

Bender, Barbara 1998. Stonehenge. Making Space. Berg

Cresswell, Tim 2015 (2nd edition). Place. An Introduction. Wiley Blackwell.

Davies, John 2007 (3rd edition). A History of Wales. Penguin.

Edwards, Hywel Teifi 1990, 2016. The Eisteddfod. University of Wales Press

Fagan, Garrett G. 2006. Diagnosing Pseudoarchaeology. The attraction of non-rational in archaeological hypotheses. In Fagan (ed.). Archaeological Fantasies. Routledge, p.47-70

Farley, Julia and Fraser Hunter 2015. Celts: art and identity. The British Museum and National Museums of Scotland

Flemming, N.C. 2006. The attraction of non-rational archaeological hypotheses. The individual and sociological factors. In (ed.) Garrett G. Fagan. Archaeological Fantasies, Routledge, p.47-70

Fowle, Francis 2015. Chapter 10. The Celtic Revival in Britain and Ireland. Reconstructing the Past c.AD1600-1920. In Farley, Julia and Fraser Hunter 2015 (eds.), Celts: art and identity. The British Museum and National Museums of Scotland, p.236-259.

Green, Miranda J. 1997. Exploring the World of the Druids. Thames and Hudson

Hewison, R. 1987. The Heritage Industry. Methuen

Hobsbawm, Eric 1983. Introduction: Inventing Traditions. In Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds.). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press, p.16-43

Hobsbawm, Eric and T. Ranger 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press

Holtorf, Cornelius 2005. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas. Archaeology as Popular Culture. Altamira Press

Hughes, Bettina 2006. Pseudoarchaeology and nationalism. Essentializing the Difference. In (ed.) Garrett G. Fagan. Archaeological Fantasies, Routledge

Jenkins, Geraint H. 2007. A Concise History of Wales. Cambridge University Press

Kemp, Barry 2010. Druids. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press

Kightly, Charles 2003. Castell Dinas Brân Llangollen. Denbighshire County Council (bilingual booklet with excellent illustrations, artist reconstructions, photographs and information)

Lovata, Troy 2007. Inauthentic Archaeologies. Public Uses and Abuses of the Past. Left Coast Press