Introduction

The new Gladiators of Britain exhibition at the Grosvenor Museum fits the archaeology of a huge story very cleverly into a relatively small space, with a great many remarkable objects that have been very well chosen to illustrate the topic.

The new Gladiators of Britain exhibition at the Grosvenor Museum fits the archaeology of a huge story very cleverly into a relatively small space, with a great many remarkable objects that have been very well chosen to illustrate the topic.

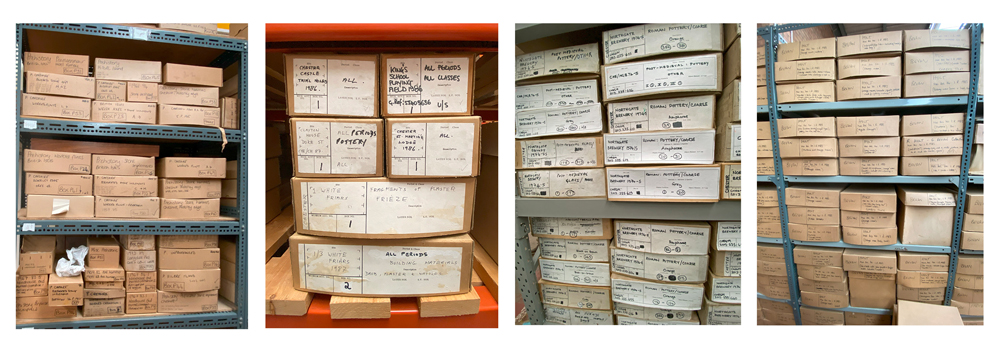

Thanks to Chester Archaeological Society I was lucky enough to be one of a group who were invited to a guided preview of the exhibition in late September 2025, just as it was opening. Many thanks to Pauline Clarke (Excursions Officer at Chester Archaeological Society) and Elizabeth Montgomery (Grosvenor Museum) for organizing our visit. Liz took us around the exhibit in two groups, and explained how the original exhibition had been organized by Glynn Davis, Senior Collections & Learning Curator from Colchester and Ipswich Museums, who had arranged for the loan of objects from both Chester’s Grosvenor Museum and London’s British Museum, partly to contextualize the remarkable and substantially important find of the Colchester Vase, shown both in the above poster and in photographs below. When this exhibition had closed, the various parties who had contributed to the Colchester exhibition were approached with a view to loaning the same objects to enable a travelling exhibition, which is what we see at the Grosvenor today, using objects and interpretation boards to introduce gladiatorial contests in Britain.

xxx

The Chester Amphitheatre

Before talking about the exhibition I though that it might be useful to put it into the context of the Chester amphitheatre. For those completely happy with the history of the Chester amphitheatre, what amphitheatres were for and the roles they performed, do skip ahead.

Rome’s Colosseum, which opened in AD 80, shown on a sestertius coin, on display at the Gladiators of Britain exhibition

Gladiatorial conquests took place in amphitheatres. The best known amphitheatre in Europe is Rome’s own stone-built Colosseum, which remains even today a stunning piece of architectural ambition, remarkably preserved and awe-inspiringly vast. The exhibition has a video running on a small tablet that shows a super 3-D reconstruction of what the Colosseum may have looked like in the past (by Aleksander Ilic). It provides a sense not only of an amphitheatre’s structural components but also of its monumental grandeur, reflecting its importance to Roman ideas of the necessities of urban infrastructure and social identity.

Like all other Roman military centres and towns, Chester (Roman Deva), established c.AD 74/75 was provided with an amphitheatre, currently the largest known in Britain. As the museum curator, Elizabeth Montgomery, made clear when guiding us around the exhibit, that statement comes with the caveat that at the important northern centre of York (Eboracum) the amphitheatre has not yet been located, but the scale of the Chester amphitheatre is a very impressive feather in Deva’s cap. Located just beyond the southeast corner of the fortification, just beyond the city walls and the New Gate (formerly the Wolf Gate) on Little St John’s Street.

The Chester amphitheatre as it is today, showing the small room that housed the shrine to Nemesis at bottom right

Britain was attractive to Rome as a target for invasion partly because, at the edge of the known world, it was an quick win for both Julius Caesar and then Claudius. It was far more prestigious to expand the Empire to its geographical limit than to merely curate its existing holdings. It is clear too that by the first century AD the Romans stationed on the Rhine had begun to become materially aware of Britain via her trading relationship with Gaul, benefitting from her produce, raising an awareness of her resources, and providing a strong secondary reason both for the Claudian invasion and for sustained occupation. Although Britain remained a peripheral province in a world where Rome was the centre of the geographical and cultural universe, the province had successive governors who were responsible for maintaining Britain as a component part of the Empire, with most of the infrastructure to mark it out as Roman territory. Every major fortress and town boasted an amphitheatre and Chester had one from shortly after the establishment of the legionary fortress in the first century AD.

A wall map from the exhibition showing the location of 17 known amphitheatre or amphitheatre-like structures in Britain

An amphitheatre such as the one we have in Chester was multi-functional. Although usually exclusively associated in people’s mind with spectacular and often gory action, where trained gladiators fought both other humans and wild animals, it was also used to execute criminals, to host military displays, to offer less lethal forms of entertainment and to display religious ceremonies and rituals. It also doubled up as an additional training space for the military, only a very short march from the parade ground that was on today’s Frodsham Street, where training and drilling, manoeuvres and tactics, to prepare soldiers for the realities of military engagement against a potentially fractious population; and at the same time kept large numbers of men sufficiently busy to minimize the disputes that might break out.

Because many of the activities, particularly the gladiatorial events, attracted large audiences (in their 1000s), they had in common with football stadiums that they were designed to accommodate a large number of spectators, funnelling them via staircases and ramps to the raked seating, providing them with ease of access and clear visibility of the spectacle that unfolded below, a major task of civil engineering based on an understanding of crowd control. The large number of entrances at the Chester amphitheatre is indicative of this understanding of how people flowed into a central location.

Sadly, although the Chester amphitheatre may have been used following the abandonment of Britain in AD 410 as a local defensive enclosure, the amphitheatre’s vast walls were subsequently robbed for building materials so thoroughly that it was reduced to it to nothing more than its foundations and the arena floor. This denuded space was subsequently used as a dump, slowly filling in, and eventually becoming completely covered over and forgotten. Buildings and gardens obliterated all evidence, with only Little St John’s Street, bending in a puzzling way, following the old line of the amphitheatre walls. Perhaps the first hint that an amphitheatre may have been part of the Roman footprint of Chester was a slate plaque found in 1738 that showed a gladiatorial scene.

The Chester amphitheatre was rediscovered in 1929 when a new extension to the the Georgian and Victorian Dee House Ursuline Convent School, still sitting over the southern part of the amphitheatre, (and now known simply as Dee House), required a new basement for heating equipment, and the works that followed encountered Roman remains. These were quickly recognised by W.J. Williams of the Chester Archaeological Society, who knew of the slate plaque, and shortly afterwards trial trenches were excavated by the Grosvenor Professor Robert Newstead of the Grosvenor Museum and Professor J.P. Droop, confirming that this was indeed the Roman city’s amphitheatre.

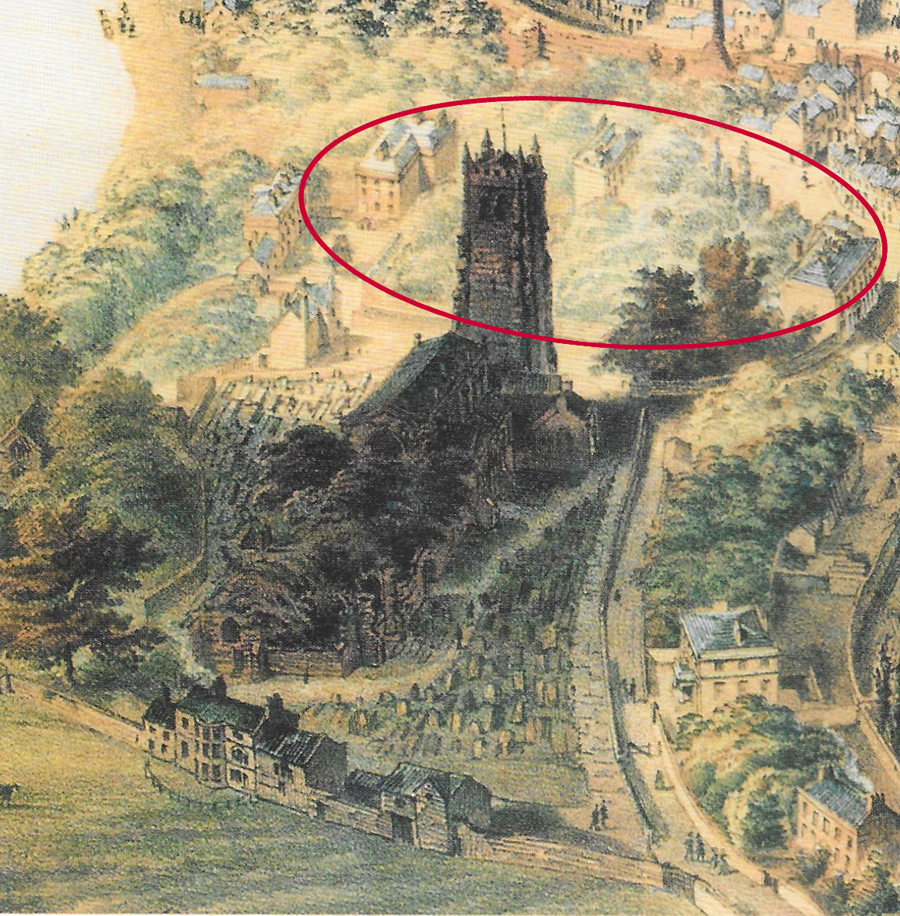

Detail of John McGahey’s 1852 painting of Chester from an air balloon (with my rough indicator of location of amphitheatre in red show how completely the amphitheatre area was covered over). Source: Ainsworth and Wilmott 2005 / Chester City Council

The site was already under threat from a new road, preparatory work for which had already taken place to run it across the centre of what was now known to be the amphitheatre. The public and heritage organizations instantly responded, and different sources of pressure caused the plan to be cancelled. Chester Archaeological Society (C.A.S.) took the lead in raising funds to clear the site and enable access for further excavations. Although these plans were interrupted by the Second World War (during which air raid shelters were dug into the amphitheatre, destroying archaeological material), these excavations took place in the 1960s, lead by F. Hugh Thompson, who proposed a phased build for the amphitheatre. In the 1990s a proposal to develop the site as a heritage destination led to planning permission for the Grade II listed Dee House to be knocked down to enable the excavation of the land beneath, but this met with financial problems, the plans faded and the planning permission lapsed in 1995 (a real lost opportunity). In 2000 the site was again excavated, this time by Keith Matthews of Chester Archaeology, who revealed more data and came to different conclusions about the phasing the amphitheatre.

In January 2003 Chester City Council joined forces with English Heritage to initiate the Chester Amphitheatre Project, covering both the amphitheatre and flanking areas. Objectives included non-invasive survey, excavation where appropriate and publication of the findings. The work took place between 2004 and 2007, led by Dan Garner (Chester City Council) and Tony Wilmott (English Heritage). The survey and excavations between 2005-2006 led by Tony Wilmott and Dan Garner, published in 2018, were particularly informative. The presence of the listed building Dee House on the other side of the site, although derelict, has prevented any further progress being made.

Phasing of the amphitheatre shown in blue (first amphitheatre) and orange (second amphitheatre). Source: Ainsworth and Wilmott 2005, p.23

The outcome of all this work has been a narrative of the large oval (rather than elliptical) amphitheatre’s two-phase construction. The first phase was erected early in the fortress’s history probably shortly after the establishment of the legionary fortress after AD 74/75. The early date of the amphitheatre at around AD80 is not unusual, with other early examples known from, for example, Dorchester, Silchester, Cirencester and Caerleon. The second amphitheatre has destroyed some of the evidence of the first. The first amphitheatre was built in more than one phase, but it appears to have matured as a wooden scaffold holding seating, with a wall at its back, and another wall separating the seating from the arena. The access to upper levels was via an external staircase, an arrangement that is otherwise only known from Pompeii at a similar date. An interesting feature of the early amphitheatre phase is a small painted shrine dedicated to the deity Nemesis, which was retained in the second amphitheatre.

The second main phase of amphitheatre construction resulted in Britain’s biggest example of this type of building. A new outer wall was built following the line of the earlier amphitheatre, a vast 2m (6ft 7ins) thick and 1.8m (5ft 11in) outside the outer wall of the first structure. The original four entrances identified in the first amphitheatre were retained but new entrances were added that lead to the interior (vomitoria) to allow access to upper seating, suggsting that the outer wall was much higher than the earlier amphitheatre, an impression that is reinforced by the sheer size of the new outer wall. As Willmot and Garner say (2018) “its size; the number, complexity and organization of entrances and the treatment of the exterior facade all place it in an architectural class beyond that of the other amphitheatres in the province.” It is estimated that the new amphitheatre could have accommodated up to between 7500-8000 spectators. It is to this phase that the tethering stone belongs, as well as a coping stone (rounded stone topping for a wall) that contains the inscription “SERANO LOCUS” (see photo of both at the end of the post).

Julian Baum’s incredibly life-like reconstruction of Roman Chester, showing the dominance of the amphitheatre, with the parade ground to its north. See more details of the amphitheatre on Julian Baum’s site at https://jbt27.artstation.com/projects/bKDayr?album_id=332464 Copyright Julian Baum, used with kind permission (click to expand)

As well as being essentially a part of the urban townscape, albeit excluded from the fortress, the tall, impressive structure that would have made an impression far beyond the immediate environs of the city. The surrounding landscape would have been in no doubt that the Ro mans had arrived, settled, and were here to stay, their amphitheatre not unlike a medieval cathedral in its powerful messaging. This is abundantly clear in Julian Baum’s reconstructions, such as the one here, demonstrating how the amphitheatre could act as a symbol of Roman presence, sophistication and power. Another of Julian’s reconstructions, showing the city at sunset, is on display in the exhibition, and both clearly demonstrate how dominant a feature the amphitheatre must have been and how important it was to the inhabitants of the fortress.

xxx

The Gladiators of Britain Exhibition

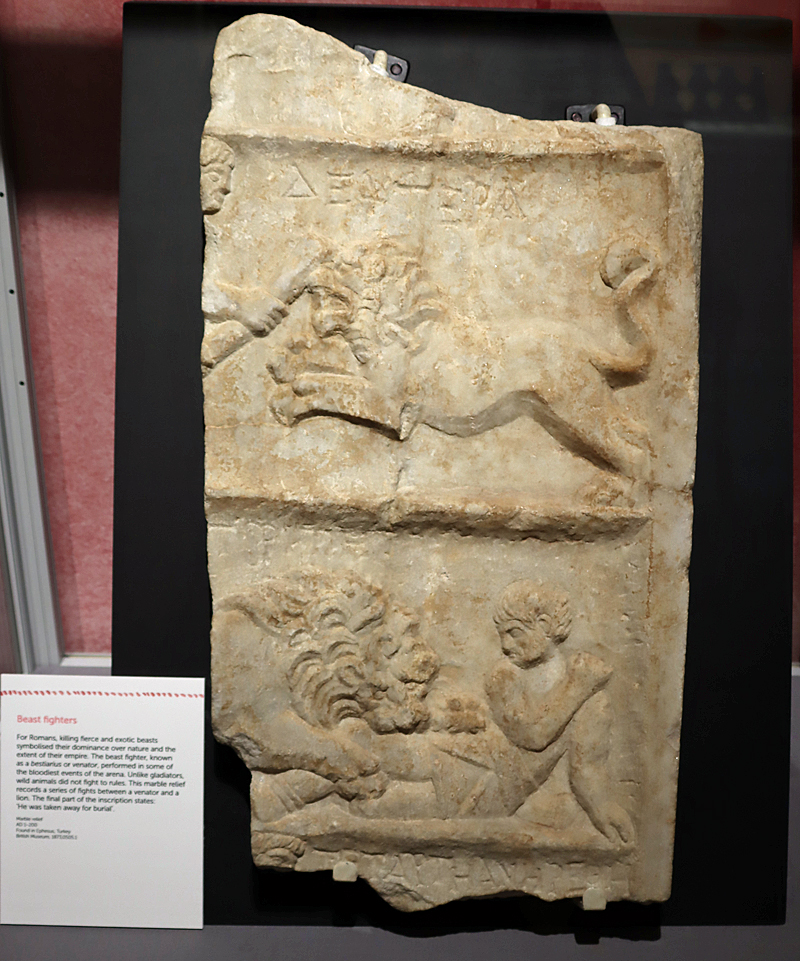

As there are no written records of the events that took place in Britain’s amphitheatres, the focus of the exhibition is on archaeological data and its interpretation. There are some very short inscriptions in stone that hint at the importance of the gladiatorial events, but the bulk of the data that informs ideas of what remains are the amphitheatres of Britain themselves, and the objects that record the spectacles that people attended. The exhibition has brought together some very evocative pieces. All the photos below are from the exhibition.

As there are no written records of the events that took place in Britain’s amphitheatres, the focus of the exhibition is on archaeological data and its interpretation. There are some very short inscriptions in stone that hint at the importance of the gladiatorial events, but the bulk of the data that informs ideas of what remains are the amphitheatres of Britain themselves, and the objects that record the spectacles that people attended. The exhibition has brought together some very evocative pieces. All the photos below are from the exhibition.

The exhibition does not attempt to analyse the Chester amphitheatre and nor does it set out to answer the bigger questions about how gladiators were trained, where they came from, or how they were deployed. What it does superbly well is demonstrate how the gladiatorial spectacle was captured both in massive architectural endeavour and in material remains preserved in the archaeological record.

The exhibition opens with some details about the amphitheatres in which gladiatorial confrontations took place. Not only is there a video by Alexander Illci showing a reconstruction of Rome’s magnificent Colosseum, but there is a fabulous, splendidly detailed coin showing the amphitheatre in raised relief, dating from AD 80. The exhibition then goes on to explore the world of gladiators via specially chosen objects that reflect the impact how amphitheatres and gladiators contributed to o Roman urban life, even far from the heartland of the Roman Empire.

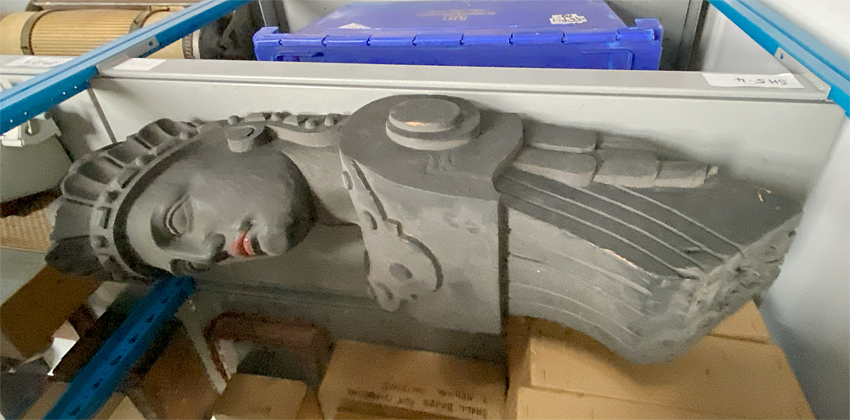

The Colchester Vase, being perhaps the key object that inspired the exhibition, is worth taking time over when you visit. Apart from the fact that it is superbly well crafted, a piece of real excellence, it tells more than one story, with each component moulded in high relief. To ensure that the vessel can be appreciated in its entirety, a mirror has been placed behind it, and the lighting highlights the relief figures very clearly. It shows a gladiator versus another gladiator, a gladiator versus a beast, and beasts chasing beasts.

Another key object in the exhibition is the helmet from Hawkedon in Suffolk, one of the most important objects to be found in connection with the history of gladiators in Britain. Unlike the Colchester Vase, or any of the other objects depicting gladiatorial action discussed below, this was design to participate in the action, worn to protect the gladiator and give him the best chance of survival. The frontpiece is modern, added to give a complete impression of what the original item looked like. Analysis of the metal suggests that it was made on the continent and hints that both it and perhaps its owenr may have travelled to Britain for participation in the amphtheatre.

Amongst many other discoveries during the excavations , the one that confirms that gladiatorial bouts undoubtedly took place in the Chester amphitheatre was a huge sandstone tethering stone, which tied animals and some human contestants alike to a central point to prevent them seeking refuge at the sidelines where they could not be viewed by the full circle of spectators (shown at the end of the post). This somewhat daunting object is on display in the exhibition. Although by far the crudest of the many lovely objects on view, it is the one that moves the exhibition from art-works to action, forcing the visitor to engage with the the very savage and bloody nature of the contests. It is one thing to look at a pretty scene on a vase or stone; it is quite another to be confronted with the block that physically chained the victim to its unavoidable fate.

Although the gladiators were the stars of the events, the members of the audience were just as important for the success and ambience of the amphitheatres, and many of the other objects in the exhibition reflect the sense of involvement and enjoyment that individuals took from amphitheatre events. One item that clearly demonstrates this sense of involvement is A coping stone, inscribed SERANO LOCUS (shown at the very end of this post), may have been part of the arena wall, perhaps marking the place (“locus”) of a spectator named Seranus. Although the more remarkable of the items in the exhibition, such as the Colchester Vase, were probably specially commissioned, other items are far less prestigious. The many oil lamps in the exhibition, showing scenes of gladiators in action, were probably purchased like souvenirs when peformances were taking place. It is thought that traces of outer buildings and the remains of food items at Chester represent snack stalls, and it is entirely likely that souvenirs could also have been sold in the same vicinity, or after the event in marketplaces.

Also on display is the shrine to the goddess Nemesis, apparently retained in the second amphitheatre after being built for the first one, adds a religious dimension to proceedings, a feature known from other amphitheatres in the Empire as well. Representing fate, Nemesis was appropriate to the prospective fortunes of both winner and loser. Nemesis was particularly appropriate for a gladiatorial outlook, whether winner or loser, representing fate. It was dedicated by the centurion Sextius Marcianus who had it made after experiencing a vision.

There are a great many more objects in the exhibition. Each has been well chosen to show different aspects of the gladiatorial experience, and each is well explained in the labelling. A wide variety of materials are represented, including stone, metals, wood and pottery, and many are decorated with great imagination. Some were component parts of the amphitheatres themselves. Others were items used in the arena, whilst a wide range of items were designed for the home. Most of these were the objects that people chose to commission or purchase, took into their homes and cared for, maintaining them in beautiful condition. As the exhibition demostrates so clearly, when they were buried, broken or lost in transit, they became archaeological remnants, and in doing so became threads of several different lines of investigation that continue to feed into broader research about the Roman occupation of Britain.

As well as the objects themselves, the information labels and interpretation boards not only inform, but create an all-encompassing experience that helps visitors to get to grips with a fascinating if gory subject matter. The interpretation boards are beautifully designed, giving the exhibition a good sense of coherence. Fortunately there is no gore on show, so this is entirely child-friendly (with games and dress-up outfits available for children) and whilst the exhibition does not judge, it leaves visitors in little doubt that this was a form of entertainment that potentially had a life or death outcome, whether for human or animal.

As well as the objects themselves, the information labels and interpretation boards not only inform, but create an all-encompassing experience that helps visitors to get to grips with a fascinating if gory subject matter. The interpretation boards are beautifully designed, giving the exhibition a good sense of coherence. Fortunately there is no gore on show, so this is entirely child-friendly (with games and dress-up outfits available for children) and whilst the exhibition does not judge, it leaves visitors in little doubt that this was a form of entertainment that potentially had a life or death outcome, whether for human or animal.

The exhibition may be small but it makes a terrific impact, making superb use of the space available, and seeking at every turn to inform and involve. The art work on the interpretation boards is attractive, and there is a lightness of touch to the whole presentation and the delicate artwork that manages to complement rather than overwhelm the exhibits and the themes. It is really well done. Don’t miss it!

With many thanks to the Grosvenor Museum’s Liz Montgomery for a really engaging guided tour of the exhibition.

The exhibition is free of charge to enter, and the museum opening times are shown on its website: https://grosvenormuseum.westcheshiremuseums.co.uk/visit-us/. Do note, as shown above, that group tours are available on Mondays, and you can phone up to arrange them. The exhibition is on in Chester until January 25th 2026.

Enjoy!

For anyone wanting to gain an impression of what the Chester amphitheatre may have looked like, the following YouTube video by 3-D modeller Julian Baum in collaboration with archaeologist Tony Willmot may help to visualize the building:

Sources and further reading:

Books and Papers

Ainsworth, Stewart and Tony Wilmott 2005. Chester Amphitheatre. From Gladiators to Gardens. Chester City Council and English Heritage

de la Bédoyère, Guy 2001. The Buildings of Roman Britain. Tempus

de la Bédoyère, Guy 2013. Roman Britain: A New History. Thames and Hudson

Carrington, Peter1994. Chester. B.T. Batsford / English Heritage

Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Keith 2001. Chester amphitheatre excavations in 2000. Chester City Council

https://www.academia.edu/4403653/Chester_amphitheatre_excavations_in_2000 (open access but requires free log-in)

Mason, David, J.P. 2001, 2007 (2nd edition). Roman Chester. City of Eagles. Tempus

Neubauer, Wolfgang; Christian Gugl, Markus Scholz, Geert Verhoeven, Immo Trinks, Klaus Löcker, Michael Doneus, Timothy Saey and Marc Van Meirvenne 2014. The Discovery of the School of Gladiators at Carnuntum, Austria. Antiquity. Antiquity. 2014, 88 (339), p173-190. Published online 2nd January 2015

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/discovery-of-the-school-of-gladiators-at-carnuntum-austria/4ACC29C5CC928A88A8A4F5ADC3E989CB

Salway, Peter 1984. Roman Britain. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press

Thompson, F.H. 1976, The excavation of the Roman amphitheatre at Chester, Archaeologia 1976, 105, p.127–239

Wilmott, Tony; Dan Garner and Stewart Ainsworth. The Roman Amphitheatre at Chester: An Interim Account. English Heritage Historical Review, Volume 1, 2006, 7

https://moscow.sci-hub.st/4860/8932e6265dd8765296a9986ccfcd3dcd/wilmott2006.pdf

Wilmott, Tony and Dan Garner 2018. The Roman Amphitheatre of Chester. Volume 1, The Prehistoric and Roman Archaeology. Oxbow (also available on Kindle, although not all of the tables are fully legible)

xxx

Websites

artnet

A Roman-Era Vase, Once Considered a Cremation Vessel, Turns Out to Be an Early Form of Sports Memorabilia for a Gladiator Fan. April 13th 2023

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/colchester-vase-sports-memorabilia-2270088

Based in Churton

Peter Carrington’s excellent guided walk of Roman Chester during the Festival of Ideas. Andie Byrnes, July 6th 2025

https://wp.me/pcZwQK-7OD

Colchester City Council

Historic Colchester Vase goes on tour with the British Museum. 19th November 2024

https://www.colchester.gov.uk/info/cbc-article/?id=KA-04817

Grosvenor Museum Chester

Gladiators of Britain exhibition

https://events.westcheshiremuseums.co.uk/event/gladiators-of-britain/

Julian Baum, VXF Artist and Illustrator

Chester’s Roman Amphitheatre

https://jbt27.artstation.com/projects/bKDayr?album_id=332464