Inside the rib-vaulted slype (or passage) passing through the east range of the cloister, to the rear of the abbey. Source: Coflein

In part 1 of this series, the establishment of the Cistercian order of monks, a branch of break-away houses based on the rule of St Benedict is explained, and its spread into Wales during the 12th century is discussed. Within this context, the foundation of Valle Crucis Abbey by Prince Madog of Powys Fadog is introduced, establishing the abbey as a member of a unique family of Cistercian houses that had its own particular Welsh character.

Part 2 looked at what each of the monastic buildings was for and how each room was used by the community of monks that lived at the abbey, potentially for the duration of their lives. It is discussed how the layout of each abbey was unique, but was guided by the basic Cistercian model of mixing domestic and religious buildings around a square, the cloister, and how this is demonstrated at Valle Crucis.

This post, part 3, takes a look at the history of the abbey buildings, pointing out how how certain architectural features indicate developments between the time of the foundation of the abbey in 1201 to its dissolution in 1537. Over this time, the occupants of the abbey responded to disasters, including fire and war; fluctuating economic conditions; changes of abbey leadership, and evolving outlooks, including eroding values, within the Cistercian order. The architecture of the claustral buildings reflects many of these changes, whether imposed upon or chosen by the community, capturing them uncompromisingly in stone.

The entire abbey is a narrative of time passing, and the east range of the cloister is a good example. In the photograph of the east range to the left, this small but well preserved section of the abbey reveals an immense profusion of architectural change, during the lifespan of the monastery and beyond its closure by Henry VIII. The combination of the row of arches above the window frames, lines of holes and protrusions and the slate-tiled roof above it all, capture how change over time is revealed in the abbey’s architecture. A simple list of just some of the architectural changes visible in the east range helps to illustrate the point.

- The rounded entrance at the left is early 13th century, one of the earliest parts of the abbey, leading into the early 13th century sacristy.

- Next to it, the ornate entrance to the book room in the middle is mid 14th century.

- At the far right is a very elaborate passage from the cloister to the eastern part of the monastery precinct, and although this incorporates an earlier 13th century arch from elsewhere in the monastery, its construction dates to the late 15th or early 16th century, only a matter of decades before closure

- The first floor was originally the monks’ dormitory when the abbey was first builtin the 13th century

- Excavations found that the east range had been much longer in the 13th century, but for reasons unknown was later reduced in size, and when this happened the latrine (marked on the above photograph by rough masonry) must have been added

- The row of holes are beam holes that supported the roof of an arcade (a covered walkway)

- The two rows of stone protrusions, corbels, that stick out of the east range above arch level date to different periods. The upper set supported the base of an ornamental parapet belonging to the early 15th century, whereas the lower set supported the roof of the arcade of the 14th century

- The blocked doorway on the first floor is 16th century, but this in turn replaces a 15th century doorway that followed the demolition of the roof that covered the walkway, when the abbot converted the dormitory into his personal apartments; a wooden staircase would have led down into the cloister

- The slate roof visible today was put on after the monastery had been abandoned, and when the east range had been converted into a farm house, as is the square window to the left of the top floor’s blocked 16th century doorway.

See the excellent booklet by D.H. Evans (B.A., F.S.A) for more in the same vein as the above (Valle Crucis Abbey by D.H. Evans, Cadw 2008). Evans walks visitors through Valle Crucis building by building, room by room, picking out features from different periods in each. In this post, I have used Evans as my main source for architectural change, looking at what happened at different periods in chronological order, so that the development of the abbey as a whole can be understood as a historical narrative.

The arrival of the Cistercians at Llanegwestl in 1201

The meagre surviving remains of Strata Marcella. Source: Coflein

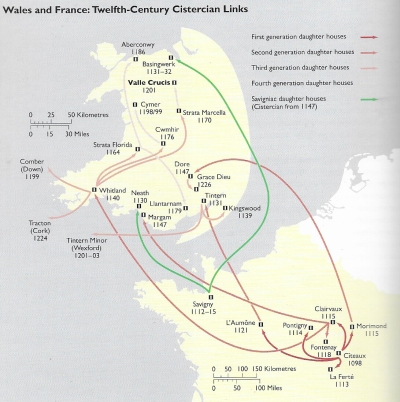

The first abbey to be established in Wales was Tintern in 1131, in Monmouthshire, South Wales, only the second abbey to be established in the British Isles. It was followed in 1151 by Whitland Abbey in Monmouthshire (also in south Wales, on the borders of Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire), founded with monks from Clairvaux Abbey, of the Cistercian order in France. Both were founded by Cambro-Normans, a bare century after the Conquest, but whereas Tintern remained firmly under Norman control, Whitland was adopted by the Lord Rhys, the Welsh prince of Deheubarth, who also adopted Whitland’s offspring, the abbey Strata Florida. The Lord Rhys established a new tradition of monasticism in Wales, referred to as Pura Wallia. As well as Strata Florida, Whitland provided the monks for Strata Marcella in 1170 and Cwmhir in 1176, which in turn provided abbots and monks for their own off-springs, resulting in three branches of Cistercian abbeys in Wales, spreading from south to north, an eastern branch a central branch and a western branch. In the eastern branch, Whitland founded Strata Marcella in 1170, and Strata Marcella in turn founded Valle Crucis, at the top of the western branch, in 1201.

Map of the cantrefi of Wales showing Powys Fadog. Source: Wikipedia

By the end of the 12th century, northern Powys (Powys Fadog) was the only territory or cantref in Wales to be without a Cistercian monastery, a matter of some discontent amongst the other monasteries in the Whitland network, including Whitland itself, Cwmhir, Strata Florida and Strata Marcella. Their abbots joined forces to persuade Prince Madog ap Gruffudd Maelor, ruler of northern Powys (Powys Fadog) to make the endowments required for the foundation of a new Cistercian monastery in northeast Wales. As described in part 1, when Prince Madog founded Valle Crucis in the commute of Iâl, it was in partnership with the Strata Marcella Abbey in mid Wales. Strata Marcella (founded 1170) provided the abbot and monks, and Prince Madog provided upland and lowland estates, mills, fishing rights and the agricultural infrastructure to enable Valle Crucis to establish and maintain itself.

The site chosen by Madog and the Cistercians for the new abbey was remote from urban life, but was not an untamed wilderness. There was, in fact, a settlement already there called Llanegwestl, and the abbey was often referred to thereafter by the former settlement’s name rather than by its official Latin name. The site was ideal for village life. On the edge of a fast-flowing and generous stream it was sheltered by tall hillsides and benefited from both upland and lowland ranges, ideal for grazing sheep and cattle respectively, and was even sufficiently fertile on the floodplains for some agricultural or horticultural activity. It was near enough to the village of Llangollen for local trade to be practical, and was within reach of outlying farms (granges) that belonged to it.

For the Cistercians, the proximity of water was integral not only to drinking, cooking and washing, but to their liturgies. At all Cistercian monasteries, a complex and often impressive network of subterranean drains and sluices was established, by which water was moved around each abbey to where it was needed. Water was also diverted form fish ponds. Inevitably, in order for the monks to move in, the villagers were forced to move out, and this was the first step taken to establish the new abbey. This was by no means an unusual, if unpopular event when a Cistercian abbey moved in, and Madog provided the dispossessed residents of Llanegwestl with land to the east, at Northcroft and Stansty (Bromfield) near Wrexham.

In 1201, the abbot and monks supplied by Strata Marcella arrived at their newly vacated destination, and started work. Although the following account is by no means not exhaustive, I have picked out some of the key points about the abbey’s architectural past to give an idea of how the abbey began, what happened to it in the course of its history, and how both accident and design led to physical changes in the function and appearance of the abbey’s surviving buildings.

safasdfa

The early 13th Century

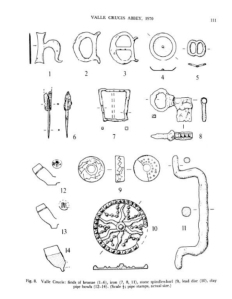

Archaeological excavations by Lawrence Butler in 1970 shows that once the villagers had been resettled, the site was cleared so that an initial set of essential buildings could be built rapidly in wood, probably including a small church, chapter house (where the monks met each morning), and sleeping and eating quarters, the core infrastructure that St Benedict had determined was the bare minimum for a monastic community. Whilst living in the temporary buildings, the Valley Crucis monks set about overseeing the construction of their stone church, starting at the east end. The church, as the focus of abbey life, was always the first building to be started, although others could subsequently start to be developed simultaneously.

The early Cistercian order required choir monks to engage in manual labour as part of their daily duties, but it is unlikely that they engaged in any significant work on building activities due to the demands of their seven daily prayer sessions. Instead, specialist joiners, masons and labourers, perhaps with the assistance of any of the conversi (lay bretheren) not actively engaged in farming and related activities, will have carried out the bulk of the work. It is thought that many of these craftsmen were itinerant, making a living out of building and repairing ecclesiastical buildings.

Each Cistercian abbey’s floorplan was an echo of the Cistercian order’s “Bernadine” plan, promoted by St Bernard of Clairvaux abbey, which itself echoed the layout of earlier Benedictine monastic establishments. All Cistercian abbeys were guided by the principal of opus Dei, God’s work, and were organized to meet the needs of regular devotion in church, scholarly activity, economic self-sufficiency, personal poverty, communal support, all embedded in routines and activities that brought these ideas together and ensured their sustainability. As Cistercian monks took a Vow of Stability, which bound them to a given monastery for life, unable to leave it without good reason and then only with the permission of the abbot, a strict regime of route and reinforcement of core values was essential, all embodied in the claustral arrangement.

As the church continued to go up and attention could be turned to the rest of the monastic complex around the cloister, one of the first tasks will have been to have laid out the claustral plan and to put in drains that would run under rooms and subsequently be covered with floors. Butler’s excavation of the site, published in 1976, found several sections of stone-lined drains that passed under floors and under the garth, but he was unable to trace sufficient stretches to map them as a network. Therefore, how they functioned as a network is still not fully understood, although they almost certainly led, at a minimum, to the kitchen, the lavatorium (water basin) in the garth, and to clear the latrine drains.

fdsfsadfasdfa

As you leave the car park, look up, and you are confronted by the impressive west face, shown in the photograph above left. It is evident, when you pause to take it in, that there are considerable differences in the masonry, which mark work carried out at different periods. There is very little of the early 13th century remaining. The most noticeable features date to over 100 years after the abbey was founded, including the lancet windows and the arch that frames them, the doorway, the rose window and the finely dressed yellow sandstone ashlar (covering stone) in which the rose window sits, and will be discussed below. The earliest parts of the west face are, unsurprisingly, at the base, where a dressed plinth in preserved, and rather severe dressed buttresses (supporting squared pillars built against the walls) rise from the ground to support the tall west face.

Vaulting shaft shown in red, string course between the two periods of masonry shown with the blue arrow, and one of the church windows, of which only the bases remain along the north wall, is shown in green. click to expand the image.

Moving inside the church, more of this earliest phase is visible in the north aisle (the wall at far left). In the early 13th Century the walls were built roughly faced rubble held in place by a lot of mortar, combining bigger and smaller pieces that would have been plastered over when finished. There is a clear change in the style of this construction, visible in the photograph to the right. The lighter, lower part of the wall, consisting of poorly sorted masonry below is the earlier wall, and the darker, more regimented masonry above the stringcourse (row of projecting stones at the top of the lighter looking stonework) followed a fire that swept through the abbey at around 1240. Also in the photograph, in the centre at ground level, is one of several “vaulting shafts,” the bases of small pillars built against the wall. These too were part of the early 13th century vision. Had fire not have swept through the part-built abbey, they would have supported stone-vaulted roofs over both aisles. Instead, the early 13th century aisle roofs were built in wood.

There are five pairs of piers, or columns. The first four of these help to mark out the original footprint of the nave, where the conversi, any guests and corrodians (paying residents) attended church services. They were separated from the east end of the church, and the abbey’s choir monks, by a stone screen, called a pulpitum. The eastern end, where the choir monks carried out liturgies and services, with the presbytery, high alter, and two chapels in each of the two transepts, was started first. The nave lay on the other side of the pulpitum. The remains of the pulpitum today are where they were moved at a later date, and this later position is marked by the base of a spiral staircase. However, the base of the spiral staircase has features that date to the early 13th century, so it looks as though that both this and the original pulpitum were simply moved one bay along, extending the nave and reducing the eastern end. Originally it will have crossed the nave at the previous set of piers. It is thought that the staircase probably led up to an organ loft.

There are five pairs of piers, or columns. The first four of these help to mark out the original footprint of the nave, where the conversi, any guests and corrodians (paying residents) attended church services. They were separated from the east end of the church, and the abbey’s choir monks, by a stone screen, called a pulpitum. The eastern end, where the choir monks carried out liturgies and services, with the presbytery, high alter, and two chapels in each of the two transepts, was started first. The nave lay on the other side of the pulpitum. The remains of the pulpitum today are where they were moved at a later date, and this later position is marked by the base of a spiral staircase. However, the base of the spiral staircase has features that date to the early 13th century, so it looks as though that both this and the original pulpitum were simply moved one bay along, extending the nave and reducing the eastern end. Originally it will have crossed the nave at the previous set of piers. It is thought that the staircase probably led up to an organ loft.

The fabulous sacristy was also built at this time, shown in the photographs below. The sacristy had doorways into the church and into the cloister. Its role was to house the vestments and altar furnishings, and any other paraphernalia required during the liturgies and services. It is an extraordinary part of the building, with a marvellous tunnel-vaulted stone roof, which is shown below, is a unique part of the abbey. Seen from the cloister, the entrance to the sacristy also dates from the early 13th Century and retains the round-topped arch of the Romanesque style (see photograph below), which sits rather strangely against the pointed arches of most of the abbey’s early and later Gothic styles, but echoes the sacristy’s interior tunnel vaulting. Today church sacristies and vestries are often rather dismal spaces, little more than untidy cupboards, but at Valle Crucis the magnificently built room was also an interface between church and cloister, and was given an appropriately dignified character.

On the left: The entrance to the sacristy with its rounded arch, dating to the early 13th century. Above it is a hotch-potch of later changes of direction. Note the pieces of facing stone above the arch and beneath the square window, coloured red by the later fire (my photo); On the right: the interior of the sacristy (source: Coflein)

All of the north transept is early 13th century. Although alterations were made at a later date, none of these survive. The north transept incorporates two chapels, each with some nice features original to its construction, including two small cupboards (aumbries) where communion vessels would have been stored, and a stone basin (piscina) for cleaning them following use. The south transept and its chapels also belong to the early 13th century, but all of its upper levels belong to the period after the fire. The entrance between the dormitory and the night stairs in the south transept dates to the 13th Century. This doorway led directly from the first floor dormitory to the east end of the church via a flight of wooden stairs (10ft / 3m) above the ground level of the church) for access to the church for the night-time liturgy.

South transept. The door to the day stairs is at far right, the stairs now long gone. To its left is the entrance to the sacristy. The big arch at the far left is the entrance to one of the two chapels.

Out in the cloister, the base of the water basin (lavatorium) is still in situ, and was almost certainly there since the establishment of the abbey. Excavations found that the east range of the cloister found that it extended for another 12m (40ft).

The east end of the abbey church, seen from the other side of the fish pond. The early 13th century pilasters with quoins are framed in red

Walking through the slype, the passageway at the end of the east range (itself of a later date), and heading outside to look back at the eastern end of the abbey, there are more original 13th century features. The lower level of walls and pointed lancet windows date to this time, although the central lancet window would have been taller, reflecting the arrangement of the west end windows. The church buttresses that lie flat against the walls (pilasters) are later in date. However, the buttresses that are visible to the left of the church, against the south transept. Instead of being completely covered in stone dressing, like the church buttresses, they are built of rubble and provided with dressed stone, quoins, on the corners.

The 12th and early 13th century Cistercians valued simplicity and rejected ostentation, associating it with adulation of the material, wealth, self-indulgence and a tendency to succumb to luxury. However, even in the early 13th century one or two pieces of decorative stonework were erected and have survived. One of the very few pieces of early ornamentation is the ceremonial arch that leads from the church in the north corridor of the cloister into the cloister, and has very beautiful sculpted columns topped with stiff-leaf capitals, which can be seen on the photograph below.

South transept arch with stiff-leaf capitals. Source: Coflein

The cemetery was also established in the early 13th Century. The abbey’s abbots and its most conspicuous contributors to the abbey’s property, possibly its founder Prince Madog, whose gravestone was found at the site would have been buried within the church. Ordinary monks would have been laid to rest in the cemetery that grew to the north and east of the abbey within the abbey precinct. A 13th century tombstone was used, post-dissolution to make a fireplace in the dormitory, which by then had been converted into a farmhouse, but is evidence for high profile 13th Century burials both within the abbey and in the abbey precinct.

Evans says that by around 1225 the eastern half of the church was well advanced, work had started on building the stone roof over the presbytery, transepts and crossing. By about 1240 the western church had been laid out and the lower parts of the walls and piers were underway.

The monastic precinct must have been growing at the same time. The full extent of the abbey’s immediate precinct is unknown, but must have been home to a number of ancillary buildings, as discussed in part 2. The core buildings that exist today did not live in a vacuum, although its full extent is unknown, The main entrance into the abbey precinct, was probably overseen by a gatehouse on the outer edges of the abbey precinct, perhaps were the buildings at the top of the lane leading to the abbey are now located. Once within the abbey precinct, visitors could attend the church to participate in services in the nave (the long, west end of the abbey church). Just as it is today, in 1201 the main entrance to the abbey church was in the west, nowadays approached from the car park.

The mid-13th Century fire and its consequences

The fire in the first half of the 13t Century swept through the abbey church, changing some of the yellow sandstone pink. The design of the church had to be changed to a rather more modest design with a wooden roof, rather than the vaulted stone roof originally envisaged

When Madog, the founder of Valle Crucis, died in 1236, his son Gruffudd II Maelor (d.1269) confirmed his father’s gifts to the monastery in a new charter, rather like renewing a contract, ensuring that the abbey retained its lands and continued to be viable.

Around 40 years after its establishment in 1201, the abbey was coming along nicely, with the stone walls rising impressively from the ground. The community must have had a very real sense of progress and achievement. The eastern end of the abbey church was approaching completion. The short presbytery at the east end of the church, where the most sacred liturgies took place, was complete. So too were the transepts, the two eastern piers and the two eastern chapels. The west end of the church was probably laid out and work was underway on the walls and piers of the nave. Buttress bases were established, ready to support the tall walls on all sides of the church. The entire building must have been a cat’s cradle of wooden scaffolding. The refectories and other south and west range buildings were probably built, but made of wood.

Although it is not recorded in any surviving documentation, it is clear that there was a major fire at Valle Crucis. It was fierce and spread fast through the wooden scaffolding, turning yellow sandstone features pink. Given that the source of the fire seems to have been the kitchen area, it is probable that the fire was connected with the preparation of food for the refectories. The refectories were probably the first to burn down.

Entrance to the nave at the west end of the church. The shape of the arch is early Gothic, but the decoration imitates Norman predecessors

Repairs were immediately implemented, but the overall design was subjected to a rethink. Instead of vaulted stone ceilings, the church aisles were provided with wooden roofs. The same walls continued to go up, but instead of mixed sizes of stone, only smaller, flatter and thinner pieces were selected, laid flat. Romanesque curves were largely eliminated, and early Gothic features dominated. It was all about height and drawing attention to it with tall, pointed lancet windows and doorways with pointed arches.

Some of these features, far more ornamental than the early 13th century vision, are clearly seen on the west front. The arched ceremonial doorway that was added to the earlier west face dates to after the fire and is also early Gothic in style. It was inserted into the west front, probably replacing an earlier and simpler version. The wall had only just reached the level of the windows by the time of the fire. When work resumed, tall lancet windows were provided with elaborate “lights” (ornamental dividers) that divided each into two.

Wall support for bell tower after the fire at the right, at the end of the south aisle and in front of an arch that opens into the cloister. Source: Wikimedia Commons, J. Armagh

The structural integrity of the bell tower that rose above the crossing point beneath the two transepts and the main axis of the church was apparently undermined by the fire. A new wall was built along the south aisle where it approached the south transept, and a filled relieving arch was added to the south wall of the tower, at the end of the south aisle.

Looking at the exterior of the east end of the church, which can be reached by passing through the passage at the end of the east range, the buttresses that lie flat, but sit flat between and either side of the church windows form a remarkable arch at the top. The upper windows, thin lancets, echo the lower windows but are incorporated into the buttresses. These feature all date to the mid 13th century , when the rebuilding took place.

The east and south ranges also had to be rebuilt and the opportunity was taken to build it of stone. Postholes within the lowest surviving course of the refectory walls show the position of the timber supports for the roof of the building. The refectory pulpit may have predated the fire, but by only a short time. The kitchen was also rebuilt at this time. The western range appears to have had relatively insubstantial stone courses, which has led to suggestions that first storey half-timbered and therefore more lightweight and requiring less support.

The later 13th Century and Edward I

Edward I, from Westminster Cathedral. Source: Wikipedia

One of the challenges that the Welsh monastic houses confronted in the latter half of the 13th Century, was the military ambition of Edward I (1239-1307) in Wales. Edward’s grandfather King John (1166-1216) had lost the bulk of the French territories that kings of England had sought to retain since the arrival of William the Conqueror. Edward I had both the leisure and the inclination to bring the rest of the island under his control. In 1276-77 and again in 1282-83 Edward concentrated his energies on Wales, allowing nothing to stand in his path, including religious houses, a few of which he made use of and some of which experienced severe damage to buildings, land and agricultural resources. Some monasteries were occupied, and many suffered financial loss due to damage of the main abbey or its related granges (farms) and by devastation of its herds and crops. At least one Cistercian abbey’s entire community, Aberconwy, was forcibly moved to new premises and its old premises were occupied by Edward’s troops. In spite of its proximity to the well-sited Castell Dinas Brân (Castle of the Crow), the ruins of which continue to overlook the Vale of Llangollen and Valle Crucis itself, Valle Crucis was subjected to the indignities of war. Interestingly, there is little evidence that the abbey core buildings. The evidence underlying the suggestion that property owned by Valle Crucis had suffered some form of financial harm comes from payments made to the abbey by Edward I following the conquest of Wales, by way of compensation. It is possible, therefore, that whilst Valle Crucis properties were damaged, the core of the abbey itself was protected.

The stone castle was built in the late 1260s by Prince Gruffudd ap Madog (c.1220-1270), but may have been preceded by a wooden structure, and it is uncertain whether Valle Crucis was built under the eye of the castle, or whether the castle came later. Dinas Brân was passed on the death of Madog to his four sons in 1236. Although it is not known which of the brothers made the decision to resort to a desperate measure, when confronted by English attack, under the Early of Lincoln, the castle was burnt by the the Welsh soldiers who held the castle in 1277, perhaps to prevent the English taking it. In fact, the English found that it could be repaired and, greatly admiring it, retained it and held it until 1282, after which it was abandoned.

Edward, a veteran of the eighth crusade, was a solid supporter of religious establishments, founding the Cistercian abbey of Vale Royal in Cheshire in 1270. Valle Crucis received £26 13s 4d in 1238 and £160 in 1284. In the absence of signs of damage to the abbey itself at that time, it seems likely that either abbey granges had been damaged, or that abbey resources, including crops and livestock, were pillaged by Edward’s armies.

Page from Peniarth Ms. 20, folio 260v. (c.1330), the earliest copy of Brut y Tywysogion. Source: Wikipedia

At some time during the later 13th Century, Valle Crucis began to be an important source of scholarly texts. Cistercians were often formidable scholars and had a mission to perpetrate both religious and historical literature. Valle Crucis is thought to have been one of the important centres of literary output, possible the primary centre, for the copying and distribution of a series of historical and religious, of which more on a future post. One of these documents is known as Peniarth MS 20 (its National Library of Wales reference number), is the one that is thought by some to have been copied at Valle Crucis. It consists of a number of different texts, including a version of the Brut y Tywysogian (Chronicle of the Princes), Y Bibl ynghymraec’, (a version of The Bible in Welsh), Kyvoesi Myrddin a Gwenddydd (the prophecy of Merlin and his sister Gwenddydd) and a summary of bardic grammar, as taught to fledgling poets.

The 14th Century

View of Valle Crucis from 1905, with gravestones in the foreground at the east end of the church, with the west front at the end. Source: Wikipedia ( Illustrations and photographs of places and events in Welsh history from a childrens book called ‘Flame Bearers of Welsh History’)

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Valle Crucis was apparently still supported by Madog ap Gruffudd’s descendants. A 1290 tombstone from the site names “Gweirca daughter of Owain,” who may have been Madog’s great granddaughter, and in 1306 Madog’s great grandson, another Prince Madog ap Gruffudd, was buried at the abbey. In 1956 his grave stone, with his grave beneath were found in front of the church’s high altar, a very high honour. The beautifully carved slab includes a heraldic shield showing a lion rampant, a sword, a spear and a riot of fruit and foliage. The inscription surrounding the shield names the prince. These grave stones were shifted from their original locations and placed in the former eastern range dormitory.

It is in the east range that the 14th century changes are most obvious. Although individual monks took a vow of poverty, the reality is that many monastic establishments could become very wealthy if they were well endowed and well managed. Individual abbots could become very highly regarded, and abbeys noted for particular achievements might host important guests. Throughout the late 14th and 15th Centuries, the role of Valle Crucis and its abbots in particular, began to change, becoming both more worldly and more prestigious, and some of the signs of these changes are visible in the architectural embellishments at this time.

The west front of the abbey was rebuilt under the abbacy of Abbot Adam, c.1330-44. Just above the rose window, is an inscription in Latin, with Lombardic lettering that reads ADAM ABBAS CECIT HOC OPUS IN PACE QUIESCAT AMEN (Abbot Adam carried out this work; may her rest in peace. Amen). The repair work restored the arch that contained all three lancet windows on the exterior, but failed to do so on the interior. The rose window was added , a popular architectural convention at this time, with eight lights, providing an ornamental focal point for the west face, inside and out. At the same time the surrounding gable was elegantly faced with sandstone blocks.

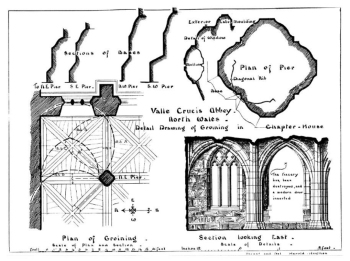

In the east range there were a number of changes. First, the entire east range was reduced from its early 13th century length by some 40ft (12m). Although the east range had a chapter house from day one, in the mid-14th century it was rebuilt and replaced with something far more ambitious than the early 13th century monastery would probably never have attempted or approved of. The entrance was replaced with something much more impressive, and the door to the book cupboard, with its ornate tracery, is now one of the most remarkable features of the ruined abbey, perhaps accompanying the rising importance of Valle Crucis as a literary centre. The ornate detail of the east range with its impressive chapter house would certainly have drawn the attention of important guests, including other monastic scholars, who came to contribute to or learn from the work of the Valle Crucis monks. It should be noted that the windows at the rear of the chapterhouse were reconstructed in the Victorian period and the flagstone floor was probably laid in the 18th century.

In the east range there were a number of changes. First, the entire east range was reduced from its early 13th century length by some 40ft (12m). Although the east range had a chapter house from day one, in the mid-14th century it was rebuilt and replaced with something far more ambitious than the early 13th century monastery would probably never have attempted or approved of. The entrance was replaced with something much more impressive, and the door to the book cupboard, with its ornate tracery, is now one of the most remarkable features of the ruined abbey, perhaps accompanying the rising importance of Valle Crucis as a literary centre. The ornate detail of the east range with its impressive chapter house would certainly have drawn the attention of important guests, including other monastic scholars, who came to contribute to or learn from the work of the Valle Crucis monks. It should be noted that the windows at the rear of the chapterhouse were reconstructed in the Victorian period and the flagstone floor was probably laid in the 18th century.

Artist’s reconstruction of the east range as it might have looked in the mid 14th Century, complete with the book room entrance, the arcade and a dormitory separated into individual cells by wooden dividers. The lean-to latrine is at the end. By Chris Jones-Jenkins. Source: Evans 2008

This trend to incorporate ornate gothic elements that had become so popular in ecclesiastical buildings was found throughout the Cistercian tradition at this time.

The lovely rib-vaulted passageway at the far end of the east range, the slype, was either completely new or, more probably, was an extension or rebuild of an earlier version. There is a photograph of it at the top of this post. A 13th Century arch was incorporated into the end of the passage, perhaps moved from the chapter house to make room for the new chapter house door. The elaborate character of the passageway is unusual, and it has been suggested that although a passage located in this position would originally have lead to the cemetery, this more ostentations version may have led to the abbot’s personal house, marking his increasingly public role at the abbey.

Stairs built into the relocated pulpitum, perhaps leading to an organ loft. Source: RCHAMW

In the late 14th or early 15th century, within the abbey church the pulpitum and east end choir were moved an entire bay east towards the end of the church, so that it now sat between the two piers immediately in front of the transepts. At the same time, a stone screen was added as an extension to the pulpitum across the north aisle. This happens at other monastic churches at this time, and may be because the space at the west end was no longer needed for lay congregations, or perhaps because there were fewer choir monks. At around the same time, the cloister arcade was probably built or rebuilt. Excavations were unable to shed any light on the subject.

During the mid-14th Century the Black Death tore through Britain, wiping out much of the population, including the conversi (lay brotherhood), which had already been on the wane during the late 13th Century. Managers and servants had to be employed to do their work. The western range, discussed in part 2, was no longer required for the conversi, and must have been adapted for other uses. Unfortunately, so little of it left that even excavations have been unable to cast much light on the subject.

The 15th and to the early 16th Century

Owain Glydwr’s coat of arms, found in Harlech. Source: National Museum of Wales

Further damage was thought to have been inflicted on the abbey during Owain Glyndŵr’s uprising between c.1400 and 1410. Excavations found evidence of another fire early in the century, which destroyed much of the western and southern ranges, the latter containing kitchen and refectory, which may or may not have been an outcome of the Owain Glyndŵr rebellion. However the fire started, both ranges were apparently rebuilt under Abbot Robert of Lancaster, who arrived in 1409 and was simultaneously bishop of St Asaph. The kitchen was supplied with a new fireplace with a large external chimney.

The abbey seems to have struggled in the following years. Unlike Edward I, Glyndŵr appears to have made no provisions to the Welsh abbeys to compensate them for damage caused, probably because although he made some short term progress, he was ultimately unsuccessful, vanishing in around 1412. It also seems as though the incumbent abbots in the years after these events, between 1419 to 1438, were unable to turn the abbey’s fortunes around. It was not until later in the century, between 1455-1527, that new abbots and new patronage combined to inaugurate a new era for Valle Crucis, again as a centre for Welsh literature and poetry, this time with an emphasis on the work of the Welsh bards rather than more scholarly historical or religious texts. Further elaboration to the design of the abbey, giving it yet another ornamental flourish, was the addition of a parapet to the church, as well as to the east range. Corbels, the protruding stone supports that remain visible today, are all that is left of this.

Valle Crucis dormitory on the first floor of the east range. Source: Coflein

It is always difficult to stifle ambition, and the abbots of Valle Crucis became increasingly differentiated from the choir monks. Three abbots in particular, attracted attention to themselves as patrons of Welsh literature and poetry between 1455 and 1527, building a scholarly reputation for Vale Crucis. These activities may be been enabled or at least assisted by the patronage of the Stanley family who were granted Bromfield and îal (today known as Yale) in 1484. Once the princes had ceased to support the abbeys, after the conquest of Wales by Edward I at the end of the 13th Century, the monasteries were forced either to make the most of their existing assets or to find new ways of generating income. This will be discussed in a future post. However, finding a new patron so late in its history was an important and very lucky break for Valle Crucis.

In the early 16th Century the dormitory had been converted into a great hall for the abbot, and at least part of the arcade had been removed to allow a staircase to be added to the former dormitory. By Chris Jones-Jenkins. Source: Evans 2008

In the 12th and 13th Centuries the Cistercian custom had been for the abbot as well as all of the brothers to share a dormitory on the first floor of the east range, but the abbot became more isolated, often moving into a private dwelling on the precinct, near to the core abbey buildings. In the 15th century at Valle Crucis the dormitory in the first floor of the east range was replaced with a new suite of rooms for the abbot, and possibly accommodation for particularly important guests. Cistercian monasteries were committed to providing for guests, but it is probably that most guests were quartered somewhere else within the precinct. Only the most prestigious of guests would have been accommodated in the east range. This required the removal of at least one side of the arcade to allow a staircase to be built from the upper storey of the east range down into the cloister.

The monks who had inhabited the dormitory must have been accommodated elsewhere in the abbey, perhaps in the west range, which had been abandoned during the mid-14th century. Although they had been housed in an open-plan dormitory in the early 13th century, this custom changed over time throughout the Cistercian order, and monks were given some privacy by separating their beds by divisions, into separate cells. As other rules were relaxed and the dormitory was co-opted by the abbot, more comfortable quarters might have become available.

By the 16th Century it was not only the living arrangements that had changed. The style of architecture now included decorative elements, and stained glass is thought to have been added to some windows. Most of the stricter Cistercian rules were relaxed. As Greene puts it “Valle Crucis had become unrecognisable as a Cistercian abbey in comparison with its early thirteenth century beginnings” (p,108).

By the 16th Century it was not only the living arrangements that had changed. The style of architecture now included decorative elements, and stained glass is thought to have been added to some windows. Most of the stricter Cistercian rules were relaxed. As Greene puts it “Valle Crucis had become unrecognisable as a Cistercian abbey in comparison with its early thirteenth century beginnings” (p,108).

Unfortunately, its comfortable lifestyle seems to have attracted quite the wrong sort of abbot between 1528 and 1535, of which more in the next post. The abbey had to be put under the care of the prior of Neath, but before he had time to make any significant input, Valle Crucis fell victim to Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. In January 1537, it was wound up. Although parts of the building were re-used for secular activities, and the church survived as a ruin, it would never again serve as a monastic establishment. The details of the dissolution and the former abbey’s subsequent history will be looked at in a later post.

Final comments

One of the striking things about Valle Crucis is the process of change visible in the architecture. People with archaeological training tend to be a bit change-fixated but at Valle Crucis the architectural developments mirror changing ideas about how strictly Cistercian rules should be obeyed, how the abbot was perceived, and what sort of role the abbey should perform in cultural terms. At the same time, traces and subsequent impacts of the mid 14th century fire can be tracked throughout the abbey. Changes to the east range, for example, reflect the switch from the early Cistercian focus on austerity and simplicity to a far less demanding approach to monastic life, which included ornamental display and the expansion of the abbot’s quarters. Modifications of the west face of the abbey church, which included the addition of an ornamental doorway and a rose window, followed damage inflicted on the building, but the opportunity was taken to add ornamental flourishes to a previously plain façade.

One of the striking things about Valle Crucis is the process of change visible in the architecture. People with archaeological training tend to be a bit change-fixated but at Valle Crucis the architectural developments mirror changing ideas about how strictly Cistercian rules should be obeyed, how the abbot was perceived, and what sort of role the abbey should perform in cultural terms. At the same time, traces and subsequent impacts of the mid 14th century fire can be tracked throughout the abbey. Changes to the east range, for example, reflect the switch from the early Cistercian focus on austerity and simplicity to a far less demanding approach to monastic life, which included ornamental display and the expansion of the abbot’s quarters. Modifications of the west face of the abbey church, which included the addition of an ornamental doorway and a rose window, followed damage inflicted on the building, but the opportunity was taken to add ornamental flourishes to a previously plain façade.

By the time of Henry VIII and the reformation of the Church, which resulted in the suppression of Valle Crucis in the first round of monastic closures, the abbey had developed in fits and starts from a strictly governed house of the Cistercian order to a community living under a less regulated, more nonchalant interpretation of Cistercian rules, barely differentiated from other monasteries that were nominally but not actually practising in the original Benedictine tradition. The monks no longer worked the land themselves, and a much more elaborate selection of foodstuffs than the Cistercian order originally permitted was consumed, including meat. Meat had been banned by St Benedict because he thought that it would inflame passions, but passions were perhaps no longer quite as worrying as they had been in the 11th Century. The plagues of the 14th Century wiped out what remained of the lay brethren, and their work was now carried out by paid servants. Income was derived not from hard work but from tithes and rent. The abbot was provided with finely specified quarters incorporating a room for entertaining, and . Although the monastic community at Valle Crucis experienced deep troughs, including fire, war, conquest and rebellion, as well as its own troubled leadership, it was also a centre of literary output and became a lodging for some of the great Welsh bards. Ambition and display had replaced austerity, self-discipline and communal privation, but the abbey had also left its mark on history with its literary output and its lovely buildings.

Next

Part 4 looks at how life was lived within the abbey, what individual responsibilities were, how the monks were organized and what sort of problems they experienced over a period of 376 years of political, social and ecclesiastical change. All parts are available, as they are written by clicking on the following link: https://basedinchurton.co.uk/category/valley-crucis-abbey/

dasdasd

Bibliographic sources for parts the Vale Crucis series:

For sources see the end of part 1.