This is a bit of an experiment, using my iPhone, which I’ve never tried before for video. I did a lot of camcorder videos of scenery when I lived in Aberdovey on the west coast of Wales, but fell out of the habit when I moved to the Chester area, so I am out of practice, feel very peculiar using an iPhone to do video, and hate the sound of my voice, but here we go. So here’s my two-minute introduction to the wonderful priory of St Mary and St James, aka Birkenhead Priory, for better or for worse. I’ll get better!

Author Archives: Andie

Dazzle-camouflage building on Knox Street in Birkenhead

At Birkenhead Priory the other day I very much liked this small building on Knox Street, very close to both Birkenhead Priory and the Cammell Laird shipyard. It has been painted in the style of dazzle camouflage, used in the First World War, and to a lesser extent in the Second World War, primarily to confuse submarines. “The primary object of this scheme was not so much to cause the enemy to miss his shot when actually in firing position, but to mislead him, when the ship was first sighted, as to the correct position to take up. Dazzle was a method to produce an effect by paint in such a way that all accepted forms of a ship are broken up by masses of strongly contrasted colour, consequently making it a matter of difficulty for a submarine to decide on the exact course of the vessel to be attacked” (Norman Wilkinson, 1969, A Brush with Life, Seeley Service, p.79, quoted on Wikipedia).

At Birkenhead Priory the other day I very much liked this small building on Knox Street, very close to both Birkenhead Priory and the Cammell Laird shipyard. It has been painted in the style of dazzle camouflage, used in the First World War, and to a lesser extent in the Second World War, primarily to confuse submarines. “The primary object of this scheme was not so much to cause the enemy to miss his shot when actually in firing position, but to mislead him, when the ship was first sighted, as to the correct position to take up. Dazzle was a method to produce an effect by paint in such a way that all accepted forms of a ship are broken up by masses of strongly contrasted colour, consequently making it a matter of difficulty for a submarine to decide on the exact course of the vessel to be attacked” (Norman Wilkinson, 1969, A Brush with Life, Seeley Service, p.79, quoted on Wikipedia).

The moment I saw it, it reminded me of a 1919 painting by Edward Wadsworth (1889 – 1949) that I have hanging in my spare bedroom, showing a ship in dry dock in Liverpool receiving its new paint job. Wadsworth painted in the style of the Vorticists, whose best known proponent was Wyndham Lewis, inspired by machinery and industry, and focused on clean lines, hard edges and planes of strong colour. The dazzle ship was a near perfect subject matter for this style of painting, and Wadsworth was in an ideal position to get up close and personal with his subject matter, as in the First World War he worked as an intelligence officer, and one of this responsibilities was implementing dazzle camouflage designs for the Royal Navy.

The moment I saw it, it reminded me of a 1919 painting by Edward Wadsworth (1889 – 1949) that I have hanging in my spare bedroom, showing a ship in dry dock in Liverpool receiving its new paint job. Wadsworth painted in the style of the Vorticists, whose best known proponent was Wyndham Lewis, inspired by machinery and industry, and focused on clean lines, hard edges and planes of strong colour. The dazzle ship was a near perfect subject matter for this style of painting, and Wadsworth was in an ideal position to get up close and personal with his subject matter, as in the First World War he worked as an intelligence officer, and one of this responsibilities was implementing dazzle camouflage designs for the Royal Navy.

I would love to know who came up with painting the building on Knox Street in the same style. If you know anything about it, do let me know.

Below is a painting from the Merseyside Maritime Museum showing the Walmer Castle painted in her dazzle camouflage. “The Walmer Castle was launched in 1901 for the recently created Union Castle Mail Steamship Company. The ship sailed between Southampton and Cape Town and in 1917 was requisitioned by the British Government. It is seen here dazzle painted for use as a troop ship in the North Atlantic. Walmer Castle survived the war and was broken up in 1932″ (National Museums Liverpool).

A visit to the 12th century Birkenhead Priory #1 – The Medieval buildings

Introduction

Birkenhead Priory is one of the most enjoyably unexpected places I have visited in the region, even more surprising than a Roman bath-house embedded in a 1980s Prestatyn housing estate. The priory site incorporates both the remains of the 12th century monastic establishment and the ruins of St Mary’s 1822 parish church with its surviving tower and terrific views. On all sides the site is surrounded by both heavy and light industry. Cammell Lairds shipyard not only butts up against the south and east walls, but purchased part of the priory’s former churchyard and cemetery for its expansion and the building of Princess Dock. On the other sides are warehouses and commercial units. The result is that in spite of the clanging and banging from the vast ship under construction immediately next door (fascinating in its own right), the obvious and somewhat inescapable cliché is that the ruins of the priory and parish church are an oasis of peace in the midst of all the busy activity. The small but quiet stretches of grass, the trees and the wild flowers contained within the remains of the priory site are a treat, and the splendid views from the top of St Mary’s tower are a powerful reminder of how the world has changed since the foundation of the priory.

I have divided this post into two parts, because there is so much to say. A visit to Birkenhead Priory is really five visits in one. In chronological order, a visit to the site provides you with the following heritage:

1) The priory, established in the 12th century and built of red sandstone, is the oldest part of the site and the star turn with its vaulted undercroft and chapter house

1) The priory, established in the 12th century and built of red sandstone, is the oldest part of the site and the star turn with its vaulted undercroft and chapter house- 2) St Mary’s parish church was built next to the ruins in 1821 to serve the growing community, its gothic revival windows wonderfully featuring cast iron window tracery

- 3) The priory’s scriptorium over the Chapter House, now with wood paneling over the sandstone walls, is the exhibition area for the Friends of the training ship HMS Conway,

- 4) The Cammell-Laird shipyard is hard up against the priory’s foundations and fabulously visible from St Mary’s Tower. When it wished to expand into the church’s churchyard, it purchased the land and re-located the burials

- 5) St Mary’s Tower, which is open to the public with amazing views from the top, is now a memorial to the 1939 HMS Thetis submarine disaster in the Mersey.

In this part, part 1 I am taking a look at the priory. In part 2 I have looked at the post-dissolution history of the site; the 1821 construction of St Mary’s parish church; the memorial to HMS Thetis and the display area for HMS Conway. I will tackle Cammell Laird’s separately, as I suspect that it will be very difficult to handle in a single post, and I need to do a lot more research before I make the attempt to summarize its history.

Birkenhead in the foreground with the manor and ruins of the monastery, and Liverpool in the background over the river, c.1767, showing just how isolated Birkenhead remained even in the 18th century. Attributed to Charles Eyes. Source: ArtUK

Foundation of the priory in the 12th Century

The priory was dedicated to St Mary and St James the Great. There are no documents surviving from the priory, and none of its priors became important in other areas of the church or in life beyond the priory, so most of the information comes from other sources of documentation as well as from the architecture itself. Its principal biographer, R. Stewart-Brown, writing in 1925, commented that it was “not possible to compile anything in any degree resembling a history of this small and obscure priory,” but the result of his work was an impressive overview of the priory, its financial stresses and its involvement in the Wirral as a whole and the Mersey ferry in particular. Much recommended if you can get hold of it. Although not certain, is thought that the priory was founded in the mid-12th century by one of William the Conqueror’s Norman followers who was rewarded for his service to the new king and the local earl Hugh Lupus with land on the Wirral. His name was Hamon (sometimes Hamo) de Massey from Dunham Massey, the second baron, who died in 1185, suggesting that the priory was founded before this date, probably in the middle of the 12th century.

Exterior of the west range, showing the two big windows that illuminated the guest quarters, the one on the left heavily modified.

The priory was established on an isolated headland, surrounded on three sides by water. Hamon almost certainly took as his model for the priory the abbey of St Werburgh in Chester (now Chester Cathedral) which was founded in 1093 by Hugh d’Avranches, also known as Hugh Lupus. Hugh Lupus had convinced St Anselm of Bec (later Archbishop of Canterbury and after his death canonized) to come and establish St Werburgh’s, and it was organized along classic Benedictine lines, about which more below. The founding of a monastic establishment was seen as a Christian act, a statement of piety and devotion, and was most importantly a precautionary investment in one’s afterlife, securing the prayers of the monks, considered amongst the closest to God, throughout the entire lifetime of the monastery

A priory was smaller and inferior in status to an abbey and was was often dependent (i.e. a subset) of an abbey, and answerable to it. It is possible that the much larger and infinitely more prestigious St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester supplied the monks to establish Birkenhead Piory, but there is no sign in the cartularies (formal documents and charters) of St Werburgh’s that there was any ongoing formal connection between the two. The difference between a non-dependent priory and an abbey was usually that the priory did not have sufficient numbers to be classified as an abbey, or that it had not applied for the royal stamp of approval required for the more senior status of an abbey. The minimum requirement for the foundation of a Benedictine abbey was 12-13 monks. A 16th century historian suggested that there were 16 monks, but it is by no means clear where this figure came from. Twice during the 14th century it is recorded that there were only five monks at the priory, and it is very likely that the priory remained too small to become an abbey.

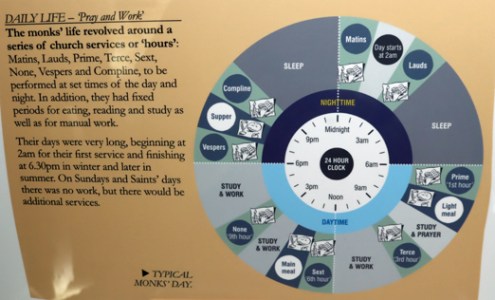

The typical monastic day in a Benedictine monastery. Not a great photo, but a very nice representation from a display in the museum area in the undercroft

The Benedictine Order was not the oldest of the monastic orders in Britain, but following the Norman Conquest it became the most widespread. It was named for St Benedict of Nursia who, in the 6th century, set out a Rule, or set of guidelines, for his own monastery. This spread widely and became the basis of many monastic establishments setting out to follow his example. The Benedictines had been well established in France at the time of the Conquest, and sponsorship by incoming Normans, granted land by William the Conqueror, ensured that they spread rapidly in England, and later Wales, Scotland and Ireland. Benedictine monasteries were all built to a standard architectural layout, with minor deviations, based on both religious and administrative requirements.

The monastic buildings

Plan of the Birkenhead Priory site. Source: Metropolitan Borough of Wirral leaflet (with my annotations in colour). North is left, south right.

If you take the guided tour, which I sincerely recommend, you begin your tour in the undercroft, now used as a museum / display space. Most helpfully it has a scale model of the priory with Stewart-Brown’s 1925 site plan, both of which help you to orientate yourself and get a sense of how the ruins were once a complex of buildings that defined and enabled a monastic community, combining religious, administrative, domestic and other functions. In the plan on the left, with the surviving remains of the priory outlined in red, the site of the priory church outlined in orange and remains of the 1822 St Mary’s Church outlined in green. The blue margin indicates the shipyard over the priory wall. The numbers on the plan are referred to in the description below. You can download a copy of the map (without the coloured additions) as a PDF here.

Like St Werburgh’s Abbey, the priory buildings were made of locally available red sandstone. Like all monasteries based on Benedictine lines, the monastic site plan began with a square. The bigger the monastery envisaged, the bigger the square. This was known as the garth (1 in the plan on the left), and was either a grassed area or a garden. Surrounding this was the cloister, a covered walkway that served as a link between the buildings that were erected around the garth, and where desks were usually arranged so that the monks could work. This was a secluded space, confined to the inmates of the monastery.

Model of the priory church and claustral buildings in the priory’s museum space in the undercroft showing a possible layout of the church. The chapter in this view is hidden behind the tower.

The most conspicuous of the buildings would have been the one that no longer stands: the church and its tower (4 on the plan above, outlined in orange), which made up one side of the cloister. Traditionally in Benedictine complexes this was built on the north side of the garth, making up an entire side of the cloister, in order protect the rest of the buildings and allow light into the garth and the other cloister buildings, but at Birkenhead Priory’s church was on the south, possibly to protect the claustral buildings from the winds whistling down and across the Mersey. The model and plan show that the 13th century church was built in the standard cross-shape. It featured a long nave at the west end (where the public were permitted to observe religious ceremonies), and a surprisingly long east end (where the ceremonies were performed) with two side-transepts, which were usually used as chapels for commemorating the dead and a tower over the crossing. A pair of aisles flanked the south and north transepts as show above. When it was first built in the 12th century, the church would have been much smaller and probably smaller than this footprint.

View of Birkenhead Priory by Samuel and Nathan Buck in 1726, showing the remains of the church’s northern arcade. Source: Panteek

The entrance to the chapter house with its Norman arches. You can clearly see the difference between the 12th century chapter house masonry and the 14th century scriptorium above with its gothic window and tracery. The tower in the background belongs to the 19th century church.

The chapter house (2) is the oldest of the Birkenhead Priory buildings, the only one remaining that dates to the 12th century. The building of the priory church, being the place where the main business of praising God took place, was usually started straight away, but the chapter house was often built in tandem as this was also of fundamental importance to a monastery. This is where the everyday business of the priory was attended to, from the day-to-day administration and disciplinary matters, to the daily readings of chapters of St Benedict’s Rules or other improving texts such as excerpts from one of the many histories of saints (hagiographies). The Birkenhead Priory’s original medieval chapter house is a gorgeous. The vaulted roof of the chapter house is superb (see the photo at the very top of this post), and although the windows have been altered over time, one of the deep Norman Romanesque window embrasures survives, and is a thing of real beauty (see below). The stained glass is all modern, but all are nicely done, the one over the altar by Sir Ninian Cowper combining religious themes relevant to the house (St Mary and St James flanking Jesus) with two prestigious characters from the priory’s own history (its founder Hamo de Massey and its two-time visitor Edward I). Gravestones from the medieval cemetery have been incorporated into the floor around the post-Dissolution altar. In the medieval priory, there would have been no altar in the chapter house, but following the Dissolution the chapter house was converted into a chapel and is still used for weddings, funerals and baptisms.

Over the top of the chapter house, a scriptorium was added in the 14th century. In theory this was where the copying of books took place, but it has been pointed out that this was a particularly large space for such an activity, and it may have been used for something else, or for a number of different activities. Today it is the display area for the training ship HMS Conway, and at some point in the 19th or early 20th century was provided with panelling and has some very fine modern stained glass by David Hillhouse. This modern usage will be discussed in part 2.

Opposite the chapter house the remains of the west range (7-11) survives, which was again a two-floor building separated into a number of different spaces It seems to have been divided into two, with the northern end and its big fireplace reserved for guests, and the southern end, with an entrance into the cloister, seems to have been split into two floors, with a fireplace on each, for the prior’s personal quarters, which would have included a private parlour that he could use for entertaining VIP guests. Although it’s not the most aesthetically stunning of the surviving claustral buildings today, the stonework displays a fascinating patchwork of different features and alterations that reflect many changes and refinements in use over time and are still something of a fascinating puzzle.

Opposite the chapter house the remains of the west range (7-11) survives, which was again a two-floor building separated into a number of different spaces It seems to have been divided into two, with the northern end and its big fireplace reserved for guests, and the southern end, with an entrance into the cloister, seems to have been split into two floors, with a fireplace on each, for the prior’s personal quarters, which would have included a private parlour that he could use for entertaining VIP guests. Although it’s not the most aesthetically stunning of the surviving claustral buildings today, the stonework displays a fascinating patchwork of different features and alterations that reflect many changes and refinements in use over time and are still something of a fascinating puzzle.

Remodelling in the 14th century created the undercroft and the refectory above it, as well as the kitchen. The undercroft (14), once used as a storage space, with the original floor intact. The investment in the lovely architecture may indicate that before it was used as a storage area, it had a more high profile role, perhaps as a dining area for guests. Above it was the refectory, unlike St Werburgh’s, Basingwerk Abbey or Valle Crucis Abbey, all of which had refectories at ground level. It was reached by a spiral stone staircase leads up to this space today.

The kitchen was apparently to the north of the west range, and connected to it, as shown on the above plan (12). This was convenient for the guest quarters, but not quite as convenient for the refectory over the undercroft, from which it was divided by a buttery (or store-room, 13), over which a guest room was also installed. The kitchen was apparently a stand-alone structure made mainly of timber, and this may have been because kitchen fires were so common, and building the kitchen slightly apart from the main monastery would have been a sensible precaution. Kitchen fires are thought to have been the cause of several devastating scenes of destruction in monastic establishments, spreading quickly via roof timbers and wooden furnishings.

The kitchen was apparently to the north of the west range, and connected to it, as shown on the above plan (12). This was convenient for the guest quarters, but not quite as convenient for the refectory over the undercroft, from which it was divided by a buttery (or store-room, 13), over which a guest room was also installed. The kitchen was apparently a stand-alone structure made mainly of timber, and this may have been because kitchen fires were so common, and building the kitchen slightly apart from the main monastery would have been a sensible precaution. Kitchen fires are thought to have been the cause of several devastating scenes of destruction in monastic establishments, spreading quickly via roof timbers and wooden furnishings.

Between the chapter house and the north range, which contained the undercroft and refectory, was an infirmary (19 on the plan) and the dormitory (18) side by side, each accessible from the cloister. The infirmary was for the benefit of the monks, and was where those who were sick or injured or suffering the impacts of old age were cared for.

Sources of income and financial difficulties

Carved head in the side of the fireplace in the guest quarters on the ground floor of the west range

Monasteries were amongst the most important land-owners in medieval Britain, on a par with the aristocracy. Their income came mainly from agricultural activities, both crops and livestock, as well as making and selling bread, beer, buttery and honey; but they might also own mills, mines, quarries and fisheries and the rights to anchorage, foreshore finds and the use of boats on rivers. For those with coastal and estuary locations with foreshore rights, there was, as Stewart-Brown lists, the benefits of flotsam (items accidentally lost from a boat or ship, jetsam (items deliberately tossed overboard), salvage from shipwrecks and keel toll. The luckier (or most strategically inclined) monasteries and churches also had pilgrim shrines, sometimes reliquaries imported from overseas. St John’s Church in Chester had a miraculous rood screen, St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester had the shrine containing the bones of St Werburgh herself, and Basingwerk Abbey had the neighbouring holy well of St Winifred. These attracted donations and bequests and were good for the settlements in which they stood, because the pilgrims needed places to stay, food and drink, and would probably buy souvenirs. Birkenhead Priory had no such shrine, but it probably felt the impact of the pilgrim route as the ferry crossing over the Mersey, which it ran free of charge, was an important link between Lancashire, west Cheshire and northeast Wales.

Some of the monastic landholdings on the Wirral. Source: Gill Chitty, on Merseyside Archaeology Society website

The original foundation of the monastery would have included both the land on which the monastery sat, funding for building it, and an economic infrastructure of landholdings as well as the income of some local churches. The long list of land-holdings sounds impressive, but most of them appear to have been quite small and scattered, some of which will have been wooded and some wasteland, not all of it suitable for cultivation or pasture. These include lands in Birkhenhead (including the home farm in Claughton with its mill), Moreton (with a mill and dovecote), Tranmere, Higher Bebington, Bidston, Heswall, Upton, Backford, Saughall, Chester, Leftwich, Burnden at Great Lever in Middleton, Newsham in Walton, Melling in Halsall, and Oxton. Either at foundation or not long afterwards, the priory was granted the incomes of the churches of Bidston, Backford, Davenham and half of the church of Wallasey, and claimed rights of Bowdon church that were disputed.

The monastery did not flourish with these assets. In spite of the claim that there were 16 monks at the time of its foundation, the records made by official church visitors suggests there were only a small number of monks at any one time (only five in 1379, 1381, and 1469, and seven, including two novices, in 1518 and 1524), and there is plenty of evidence to indicate that the priory struggled financially. Monasteries had significant overheads including feeding the community, buying tools and supplies, repairing monastic and farm buildings, appointing stewards and other employees, providing charitable alms and providing hospitality free of charge. Where they earned incomes from churches and chapels, they were also responsible for the provision of the clergy and shared part of the cost of maintaining the buildings. Ambitious priors often invested in building projects, sometimes to improve the monastic offering, sometimes for prestige, and even with donations this was usually costly. There were also occasional challenges to bequests made to churches from following generations, which involved costly legal proceedings. Balancing the books was a frequent problem for monastic establishments, and the priors of Birkenhead Priory were no different.

There were quite limited means by which the priors of Birkenhead might increase their income. The most obvious way of generating ongoing income was to acquire more land through gifts and bequests. In this endevour the priory probably had a real disadvantage in being near to both St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester and, across the river Dee, Basingwerk Abbey at Holywell. Both abbeys had significant land-holdings on the Wirral, and both had pilgrim shrines and were on pilgrim routes. Both were large and prestigious, and were far more likely to attract big gifts than a small and rather remote priory. If Birkenhead hoped to attract gifts of land, it probably had to depend on local landowners and merchants who felt a personal connection with the priory but would not necessarily have had the wherewithal to significantly change the income-earning potential of the priory, providing personal items rather than swathes of land. For these very local gifts and legacies, it is entirely possible that the priory was also in competition with contemporary parish churches on the Wirral. There are records in the early 16th century, not long before the monastery was closed during the Dissolution, that give an idea of the sort of bequests made by local people in return for requiem masses to be recited for their souls: one will provided a painting of the Crucifixion for the priory church. Another bequeathed the owner’s best horse, 10 shillings, and a ring of gold.

There were quite limited means by which the priors of Birkenhead might increase their income. The most obvious way of generating ongoing income was to acquire more land through gifts and bequests. In this endevour the priory probably had a real disadvantage in being near to both St Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester and, across the river Dee, Basingwerk Abbey at Holywell. Both abbeys had significant land-holdings on the Wirral, and both had pilgrim shrines and were on pilgrim routes. Both were large and prestigious, and were far more likely to attract big gifts than a small and rather remote priory. If Birkenhead hoped to attract gifts of land, it probably had to depend on local landowners and merchants who felt a personal connection with the priory but would not necessarily have had the wherewithal to significantly change the income-earning potential of the priory, providing personal items rather than swathes of land. For these very local gifts and legacies, it is entirely possible that the priory was also in competition with contemporary parish churches on the Wirral. There are records in the early 16th century, not long before the monastery was closed during the Dissolution, that give an idea of the sort of bequests made by local people in return for requiem masses to be recited for their souls: one will provided a painting of the Crucifixion for the priory church. Another bequeathed the owner’s best horse, 10 shillings, and a ring of gold.

As the Middle Ages progressed, populations expanded and both new and old towns began to hold markets where everyday goods and more prestigious products could be traded, even once-isolated monasteries found themselves becoming integrated into the secular world and in competition with it. It certainly did not initially help the monks at first that during the early 13th century Liverpool began to grow. Under the Benedictine rules, monasteries had an obligation to provide hospitality to visitors when required, and the Birkenhead monks ran the ferry over the Mersey as a charitable service. When the priory was first established, offering occasional hospitality and running the ferry free of charge were not onerous. This changed rapidly after 1207 when Liverpool was granted burgh status by King John, as the following translation of the original Latin charter confirms (Translation from Picton 1884):

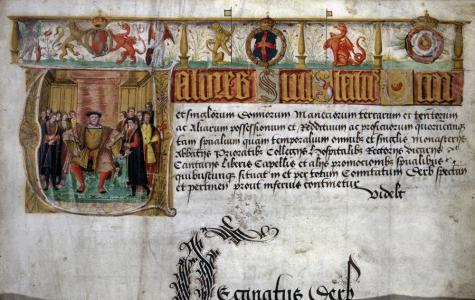

The 1207 charter of Liverpool by King John. Source: Royal Charters of Liverpool leaflet

John, by the grace of God King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy, Aquitain, and Earl of Anjou, to all his faithful subjects who may have wished to have burgages in the town of Liverpool greeting. Know ye that we have granted to all our faithful people who may have taken burgages at Liverpul that they may have all liberties and free customs in the town of Liverpul which any free borough on the sea hath in our land. And therefore we command you that securely and in our peace you come there to receive and inhabit our burgages. And in testimony hereof we transmit to you these our letters patent. Witness Simon de Pateshill at Winchester on the 28th day of August in the ninth year of our reign.

A little later Liverpool was granted the right to hold markets and fairs, and the links between Liverpool and the busy port of Chester grew to be increasingly important. There was no infrastructure to cope with this increase in human traffic. They were already offering a ferry service free of charge but even more pressing on their resources was the cost of housing guests. There were no inns between Liverpool and Chester (showing a lack of commercial ambition on the part of both Liverpool and Chester medieval merchants!), so the monks found themselves obliged to offer accommodation and food, which the rules of the Benedictine order required them to offer free of charge. This hospitality became particularly difficult if there was a spell of bad weather, during which those waiting to cross from Birkenhead to Liverpool would have to wait at the priory until the weather improved and crossings could resume. They were also were troubled with all the through-traffic that travelled along a route that ran through the monk’s Birkenhead lands close to the priory buildings.

It must have exacerbated the monks’ financial situation when Edward I visited the monastery twice with his entourage during this period. Edward’s first visit was in September 1275 for three nights, seeking a diplomatic solution to his dispute with the self-styled Prince of Wales, Llywelyn the Last of Gwynedd. His second was in 1277 for six days with the apparently dual motives of pursuing his campaign against Llywelyn and receiving a delegation from Scotland to settle a boundary dispute. Although the king would pay the costs of his entourage and horses, the cost of entertaining the king and his most senior advisors fell to the monastery. Hosting a royal entourage was notoriously expensive, and any contributions made by a visiting monarch to a monastic establishment only rarely compensated for the outlay.

One of the measures to improve their income in the 1270s involved the expense of serious litigation when incumbent prior claimed that the church had been presented in its entirety to the priory. This was disputed by the Massey family, who triumphed in the courts. Fortunately for the priory, in 1278 the 5th Hamon de Massey came to an agreement with the monks to their benefit. Other litigation occurred over pasture rights in Bidston and Claughton.

In 1284 the priory received permission from Edward I, who had probably witnessed the priory’s problems at first hand in the 1270s, to divert the road that disrupted the priory “to the manifest scandal of their religion” and to provide the priory court with an enclosure, either a ditch, hedge or wall, to preserve its privacy. This would have incurred costs, but would have eased one of the problems caused by the ferry. Rather more significant for their finances, early in the 14th century the priory was granted a licence to build and charge for guest lodgings at the ferry at Woodside, and in 1311 they were granted the rights to sell food there. It was at this time that the church was expanded, which would have been a significant project.

The first half of the 14th century had been hard for most of western Europe, with both famine due to anomalous weather conditions that caused crops to fail, followed only a few decades later by a plague that killed huge numbers of people. In Britain the famine lasted from 1315-17 and the Black Death arrived in 1348. The priory survived both the famine and the plague, as did the settlement of Liverpool, now a century old. At some point in the first half of the 14th century, the priory acquired land in Liverpool so that the monks could begin to trade their goods at market, building a granary or warehouse on Water Street (then known as Bank Street).

In 1316 the hospital of St John the Baptist in Chester was judged to be seriously mismanaged and was put into the hands of the priory, perhaps because of their experience running their own infirmary. This was a failure, merely adding to the priory’s problems, and was removed from their care in 1341.

Multiple layers in the west range, with a window added into the top of a former fireplace, blocking it, and a fireplace above it.

In 1333 Edward III requested monasteries to contribute to the expenses of the marriage of his sister Eleanor. Local monasteries who contributed included Birkenhead, which contributed £3 6s 8d and Chester’s St Werburgh’s Abbey which, bigger and more prosperous, gave £13 6s 8d. There were doubtless other payments of this sort, occasional and therefore unpredictable, and impossible to resist. The priory was also liable for taxation.

The ferry from Woodside had continued to be supplied free of charge, but the priory appealed to Edward III and was permitted for the first time to charge tolls in 1330, setting a precedent that remains today. A challenge to the monk to operate the ferry and claim the tolls, was challenged by the Black Prince in 1353, but the priory produced its charter and successfully resisted the removal of this privilege. The tolls charged were recorded at that time: 2d for a man and horse, laden or not; 1/4d for a man on foot or 1/2d on a Saturday market dasy if he had a pack

Other ways of generating income from lands to which they had rights were also explored, and from records of litigation against them, they were often accused of infringing forest law. Wirral had been defined as a forest by the Norman earls of Chester, which restricted how the land could be used. The monks were clearly assarting (cutting down wood to convert to fields and pasture), reclaiming waterlogged land, enclosing certain areas and cutting peat for fuel. The priory was able to argue special exemptions for some of the charges, and produced the charters to prove it, but at other times they were fined for the infractions. In 1357, for example, they were fined for keeping 20 pigs in the woods.

A number of monastic establishments seem to have responded to surviving the plague by redefining themselves via architectural transformations. Whatever the reasons for this trend, Birkenhead Priory was no exception and the 14th century could have been an expensive time for the monks. The frater range (including the elaborate vaulted undercroft and the refectory) was completely rebuilt and the west range was remodelled. The room today described as a scriptorium was also added over the chapter house at this time. Although Stewart-Brown suggests that much of this could have been accomplished with “pious industry . . . without much cost” with the assistance of donations of labour and money, that is probably somewhat optimistic, and there would have been an outlay. Certainly, at the end of the century the priory was considered to be so impoverished that it was exempted from its tax contribution.

A number of monastic establishments seem to have responded to surviving the plague by redefining themselves via architectural transformations. Whatever the reasons for this trend, Birkenhead Priory was no exception and the 14th century could have been an expensive time for the monks. The frater range (including the elaborate vaulted undercroft and the refectory) was completely rebuilt and the west range was remodelled. The room today described as a scriptorium was also added over the chapter house at this time. Although Stewart-Brown suggests that much of this could have been accomplished with “pious industry . . . without much cost” with the assistance of donations of labour and money, that is probably somewhat optimistic, and there would have been an outlay. Certainly, at the end of the century the priory was considered to be so impoverished that it was exempted from its tax contribution.

There is some evidence that for at least some of the Middle Ages the priory rented out land rather than working it themselves, except for their home farm at Cloughton. This had the benefit of providing a dependable income if tenants were reliable, and obviated the need to appoint managers or deal with labour and handle the sale of produce, but if the cost of living went up, the fixed income that no longer purchased what it had previously afforded, and this could represent a serious problem.

Dissolution

When Henry VIII’s demand for a divorce was rejected by the pope, the king severed Britain from the Catholic Church, creating the Church of England. This provided him with the opportunity to acquire land and valuable assets by dissolving all monastic establishments, all of which had been subject to the papacy. The spoils were to be used to fund Henry’s wars with France and Scotland, and some former monasteries were given to Henry’s supporters as rewards. To assess the potential of the monastic assets, Henry VIII commissioned the Valor ecclesiastis, a review of every monastery in the country. All monastic establishments with an annual income of less than £200.00 were to be closed as soon as possible. The first monasteries were dissolved in 1536 and the process was more or less concluded by 1540, with a handful of the more prestigious abbeys, like St Werburgh’s in Chester, converted to cathedrals. Birkenhead Priory was only earning £91.00 annually so it was amongst the first to be closed. There was no resistance by the Birkenhead prior, who was provided with a pension of £12.00 annually. The brethren were either dismissed or disseminated to non-monastic establishments.

Visiting

The car park is on Church Street, at the rear of the priory, where the cafe is also located. There is some on-street parking on Priory Street at the front of the priory. Source: Birkenhead Priory website

This is a super place, and makes for a terrific visit. Do go. You won’t be disappointed!

Even with SatNav, the big thing to remember about finding your way to Birkenhead Priory, if you are arriving by car from the Chester direction, is to do whatever it takes NOT to end up at the Mersey tunnel toll-booths 🙂 They were very nice about it, let me out through a barrier, and gave me perfect directions to get to the priory once they had freed me from the tunnel concourse. Very nice people. If Edward III was looking down, I’m sure he would have rolled his eyes in despair, given that it was he who gave the monks the right to charge for their Mersey ferry crossings.

Do check the opening times on the website, as the priory is only open on certain days and for only a few hours on those days, mainly in the afternoons. There is dedicated parking on Church Street at SatNav What3Words reference ///super.punchy.report. From there, the priory is up a short flight of steps. You can also park on Priory Street, which is where the SatNav will take you if you simply type “Birkenhead Priory” into your SatNav (at What3Words ///indoor.vibes.hips), which offers step-free access but there is limited parking there, and it is a favourite place for van drivers to park and eat their lunches so may be better used as a drop-off point before going round the the car park.

Remnants of the decorative floor tiles, now in the priory’s undercroft, which is used as a museum space

At the time of writing, a visit is free of charge, and so are the guided tours. My guide was the excellent Frank. He covered not only the priory but St Mary’s, the HMS Conway room, and the HMS Thetis memorial and, when I headed up to the top of the tower of St Mary’s, directed me to out for the dry dock where the CSS Alabama (the US Confederate blockade runner) was built by John Laird, to be discussed in Part 2. Frank was very skilled at providing sufficient knowledge to get a real sense of the place, but not so much that it became information overload. I very much appreciated this, having always found it difficult myself to strike that particular balance. I was lucky enough to have him to myself, having turned up at opening time, but I noticed that the next tour had a respectable group attending.

There is a small gift shop where you can also buy a really useful guide book with plenty of plans, illustrations and colour photographs. Please note that they are not able to take cards, and payment is cash only.

There is a small gift shop where you can also buy a really useful guide book with plenty of plans, illustrations and colour photographs. Please note that they are not able to take cards, and payment is cash only.

There are toilets in St Mary’s tower, a picnic area behind the undercroft on sunny days, and the highly rated Start Yard café is almost next door on Church Street.

For those with unwilling legs, I would suggest that apart from the tower and its 101 steps, and a flight of around 10 steps up into the scriptoruim (the display area for HMS Conway) this is entirely do-able. There are occasional single steps and uneven surfaces, and it is a matter of taking good care. As mentioned above, if you park in the carpark at the rear on Church Street, there is a flight of steps into the priory, but even if there is no space in the limited street parking available at the front of the priory on Priory Street, it is a useful drop-off point for anyone needing step-free access. You can find the SatNav references for both above.

I have posted a two-minute video of the priory, recorded on my iPhone, on YouTube:

Sources

Books, papers, and guidebooks

Baggs. A.P., Ann .J Kettle. S. J. Lander, A.T. Thacker, David Wardle 1980. Houses of Benedictine monks: The priory of Birkenhead, In (eds.) Elrington, C. R. and B. E. Harris. A History of the County of Chester: Volume 3, (London, 1980) pp. 128-132.

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/ches/vol3/pp128-132

Burne, R.V.H. 1962. The Monks of St Werburgh. The History of St Werburgh’s Abbey. S.P.C.K.

Chitty, Gill 1978. Wirral Rural Fringes Survey. Journal of Merseyside Archaeological Society, vol.2 1978

https://www.merseysidearchsoc.com/uploads/2/7/2/9/2729758/jmas_2_paper_1.pdf

de Figueiredo, Peter 2018. Birkenhead Priory. A Guidebook. ISBN 978 1 9996424 0 2

Hughes, Tony. St Mary’s Parish Church, BIrkenhead, 1819-1977. n.d.

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/wp-content/uploads/St-Marys-booklet.pdf

Picton, Sir James A. 1884. Notes on the Charters of the Borough (now City) of Liverpool. The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol 36 (1884)

https://www.hslc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/36-5-Picton.pdf

Stewart-Brown, R. 1925. Birkenhead Priory and the Mersey Ferry, and a Chapter on the Monastic Buildings. The Gift of the Directors of the State Assurance Company Ltd.

White, Carolinne 2008. The Rule of St Benedict. Penguin.

Websites

The Birkenhead Priory

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/

Buildings of Birkenhead Priory

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/about/

The medieval grave slabs of Birkenhead Priory

http://thebirkenheadpriory.org/wp-content/uploads/Graveslabs-of-Priory-Chapel.pdf

Mike Royden’s Local History Pages

The Monastic and Religious Orders in the Hundred of Wirral from the Saxons to the Dissolution of the Monasteries – A study of the Monastic history and heritage of Wirral by Norman Blake, April 2003

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/students/monasticwirral/monasticwirral.htm

The Influence of Monastic Houses and Orders on the Landscape and locality of Wirral (with particular reference to Birkenhead Priory) by Robert Storrie, April 2003

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/students/bheadpriory/bheadpriory.htm

The Medieval Landscape of Liverpool: Monastic Lands (with particular reference to the granges of Garston Hall and Stanlawe Grange) by Mike Royden, 1992

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/mikeroyden/liverpool/monastic/mondoc.htm

ArchaeoDeath

Commemorating the Reburied Dead: Landican Cemetery

https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2024/05/16/commemorating-the-reburied-dead/

Old Wirral

https://oldwirral.net/archaeology.html

Wirral Council

Making Our Heritage Matter. Wirral’s Heritage Strategy 2011-2014, 2013 Revision. Technical Services Department.

http://democracy.wirral.gov.uk/documents/s50009194/Wirral Heritage Strategy Appendix.pdf

Wirral History

Medieval Wirral (maps)

http://www.wirralhistory.uk/medieval.html

An online archive for for St Mary’s Church and the Priory, Birkenhead

History of the Priory and St. Mary’s Church Birkenhead

http://stmarysbirkenhead.blogspot.com/p/history-of-priory-and-st-marys-church.html

Leaflets

Birkenhead Priory Guide. Metropolitan Borough of Wirral.

Birkenhead Priory A4 leaflet Wirral

Liverpool’s Royal Charters

https://liverpool.gov.uk/media/ghdaoid3/liverpool-charter.pdf

St Mary’s Parish Church 1819-1977

https://thebirkenheadpriory.org/wp-content/uploads/St-Marys-booklet.pdf

Monument to the building of the Queensway Tunnel under the Mersey, Birkenhead

On a recent visit to Birkenhead Priory, which I am still writing up, I arrived some time before the Priory opened, and went for a wander. There are some great things to see in the area, but this combined monument and street light really drew the eye. I decided not to risk life and limb by flinging myself across the very busy road to read the inscription at its base, so did a web search when I returned home. It is a monument to the building of the Queensway Tunnel under the Mersey. It is Grade II listed (1217871), was designed by Herbert Rowse and erected in 1934. It was shifted from its original position in 1970 due to changes in the road layout at the tunnel approach, but originally illuminated the first concourse / plaza.

The monument has the fluted elements of a Doric column clad in impressive black granite, hints at ancient Egyptian lotus-top capitals, has a light on top, and simply yells Art Deco creativity and optimism, with a touch of eccentricity. It is such a hybrid of different ideas, incorporating ancient art and contemporary technology, and happily combining the functions of both monument and lighthouse that it has no chance of being rationally categorized. Like Greek and Roman columns or ancient Egyptian obelisks, it looks as though it ought to be in company, not standing all on its own.

The monument did in fact have a twin, but instead of standing alongside its sibling was erected over the river in Liverpool, lighting the other entrance to the tunnel. Sadly this was taken down in the 1960s, a period when so many bad decisions were made regarding architectural heritage. There was some talk in the media this time last year about erecting a replica, but I don’t know if that plan went anywhere or has been abandoned.

The inscriptions on the bronze plaques on the base display the names of the engineer responsible for the civil engineering of the tunnel, Sir Basil Mott J.A. Brodie and the architect Herbert Rowse, as well as the names of the team who built the bridge and the construction teams and committee members who oversaw proceedings. The commemorative declaration reads:

The inscriptions on the bronze plaques on the base display the names of the engineer responsible for the civil engineering of the tunnel, Sir Basil Mott J.A. Brodie and the architect Herbert Rowse, as well as the names of the team who built the bridge and the construction teams and committee members who oversaw proceedings. The commemorative declaration reads:

Queensway, opened by His Majesty King George V, 18th July 1934 accompanied by Her Majesty Queen Mary. The work on this tunnel was commenced on 16th December by Her Royal Highness Princess Mary Viscountess Lascelles, who started the pneumatic boring drills at St George’s Dock Liverpool MCMXXXIV

I love the monument. It has a real sense of joie de vivre. It is a shame that it is no longer located closer to its original position as part of the tunnel’s original architectural vision. On the upside, at least it has been preserved and not demolished like its twin. Other aspects of the original Art Deco vision do survive in situ at the tunnel entrance, shown above right.

Sources:

Ariadne Portal

Monument to the building of the Mersey Tunnel, Birkenhead Statement of Significance

https://portal.ariadne-infrastructure.eu/resource/81de5df3ed3619b3a955851dd28c44311e65fcefde36d151d655fdb6f35d49c2

Historic England

1217871

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1217871?section=official-list-entry

Chester Standard

Restoration plan for Liverpool entrance to Queensway Tunnel

https://www.chesterstandard.co.uk/news/23587848.restoration-plan-liverpool-entrance-queensway-tunnel/

Liverpool Echo

Replica monument could be installed to mark Mersey Tunnel history

https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/replica-monument-could-installed-mark-26238865

Wikipedia

Monument to the Mersey Tunnel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monument_to_the_Mersey_Tunnel

Gop Cave and Cairn near Prestatyn #3 – The vast cairn

Introduction

The cairn rising above the tree tops on Gop hill, with the cave visible as a dark line in the light limestone ridge below. Source: Coflein

Gop Cairn is at an elevation of 250m (c.820ft) above sea level on the prow of a hill overlooking the Vale of Clwyd, just outside the village of Trelawnyd (formerly known as Newmarket). It is oval rather than round, and measures roughly 101m x 78m (331 x 255ft). It is the biggest man-made prehistoric mound in Wales, and in Britain as a whole it is second only to Silbury Hill in Wiltshire.

The cave has already been discussed in part 1 (Pleistocene and Mesolithic) and part 2 (Neolithic burials).

The Excavation

Sir William Boyd Dawkins was hired by the landowner to excavate the cairn. Boyd Dawkins had a simple, though labour-intensive strategy. The plan that Boyd Dawkins made of the cairn shows the dip in the top that remains today. Boyd Dawkins speculates that this could have been caused when the cairn was later used as a source of raw materials for local drystone walling, or alternatively by subsidence due to the collapse of an underlying chamber.

Although there is a thin covering of vegetation today, the cairn was found to be built of chunks of limestone. Around the base of the cairn there seems to have been a more organized and well presented kerb of drystone walling. Ian Brown suggests that when first built, and during the period when it still retained importance, it may have “shown a dramatic whiteness set against a blue or darkening site.” The limestone ridge below, in which the cave is located and shown at the top of this post, certainly seems almost white in the sunshine, and the cairn may have had a similarly noticeable appearance, particularly given its great size.

Boyd Dawkins sunk a shaft (6ft 6 ins by 4ft / c.2m x 1.22m) vertically from the top of the cairn, which had to be shored up with timber to allow work to proceed safely. The shaft reached the former ground surface, which was formed of bedrock. A main “drift” (a mining term for a horizontal subterranean tunnel) was then tunnelled running 30ft (c.9m) to the northeast from the bottom of the vertical shaft towards the edge, followed by two shorter drifts. The hope was to find a burial chamber at the centre. It was not unreasonable to assume that there would be a burial chamber of some description. Although Neolithic chambered cairns are not common in northeast Wales (examples are Tyddyn Bleiddyn near St Asaph and Tan y Coed in the Dee valley), there are many Early Bronze Age round barrows with cists, and there are several stone-built burial sites and a stone row on the Great Orme to the west.

Unfortunately, in spite of all the hard work, all that Boyd Dawkins and his team found were fragmented animal bones, which in spite of his considerable experience identifying animal remains, Boyd Dawkins was unable to identify with certainty: “hog, sheep or goat, and ox or horse, too fragmentary to be accurately determined.” Overall, the suggestion is that these were domesticated species that could have been herded or penned in the area.

Unfortunately, in spite of all the hard work, all that Boyd Dawkins and his team found were fragmented animal bones, which in spite of his considerable experience identifying animal remains, Boyd Dawkins was unable to identify with certainty: “hog, sheep or goat, and ox or horse, too fragmentary to be accurately determined.” Overall, the suggestion is that these were domesticated species that could have been herded or penned in the area.

No artefacts were found.

Conditions were obviously very difficult, as Boyd Dawkins states: “The timbering necessary for our work was not only very costly, but rendered it very difficult to observe the condition of the interior even in the small space which was excavated.” It is possible that the chamber, if there is one, is off-centre, and that any passage leading to it is in a different direction. Until further survey or excavation work is carried out, there is no means of telling what lies beneath the surface.

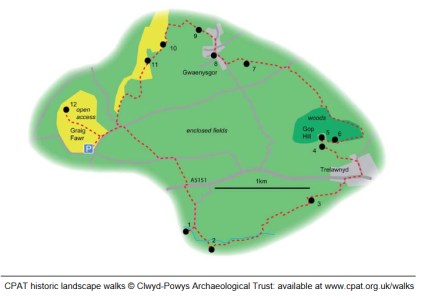

Dating the Cairn

Data for the dating of the cairn is circumstantial. Although domesticated animal species were found within the cairn, these could have been deposited at an any time from the Neolithic onwards. On the other hand, arrowheads and other Neolithic stone tools have been found on Gop Hill. According to T. Allen Glenn in 1935, Gop Hill was known locally as Bryn-y-Saethau, the Hill of Arrows, due to the large number of Neolithic arrowheads found there over the decades. Just below the cairn, just 43m (141ft) away, shown in the above photograph, is a shallow cave in the limestone ridge that contained Neolithic burials. There are ephemeral Neolithic sites nearby, identified by T. Allen Glenn during field walking during the 1920s, and there are other Neolithic cave sites in northeast Wales. At the same time, nothing significant relating to the Bronze Age has been found in the immediate area. Although Iron Age and Roman sites have been found in the area, Gop Cairn is not an Iron Age or Roman form of site, and there is no record of a medieval motte and bailey castle up on the hill. On balance, accepting that it remains speculative, it seems probable that it will turn out to be a Neolithic site if it is ever properly investigated.

Myth: “Baseless Theories”

A local writer named Edward Parry, author of Royal Visits and Progresses into Wales, written in 1851, propagated the idea that Gop Hill and its cairn were connected with the battle between Boudicca and Suetonius Pauluins in A.D. 61. It is a bizarre theory, that Ellis Davies, under the subheading “Baseless Theories” says in 1949 was a “false derivation” based on one of the names of the Gop, Cop Paulini. It is otherwise incomprehensible why Parry should have come up with the theory, but it found its way into other pamphlets and local accounts. As Davies points out in a rather aggrieved tone, “It would not be necessary to refer to these absurd stories about the association of Boudicca with Gop and neighbourhood were it not for the fact that locally they still persist!”

A local writer named Edward Parry, author of Royal Visits and Progresses into Wales, written in 1851, propagated the idea that Gop Hill and its cairn were connected with the battle between Boudicca and Suetonius Pauluins in A.D. 61. It is a bizarre theory, that Ellis Davies, under the subheading “Baseless Theories” says in 1949 was a “false derivation” based on one of the names of the Gop, Cop Paulini. It is otherwise incomprehensible why Parry should have come up with the theory, but it found its way into other pamphlets and local accounts. As Davies points out in a rather aggrieved tone, “It would not be necessary to refer to these absurd stories about the association of Boudicca with Gop and neighbourhood were it not for the fact that locally they still persist!”

The Beacon

In his 1949 book “The Prehistoric and Roman Remains of Flintshire,” Ellis Davies notes that in the 17th century there was a beacon on Gop Hill, the purpose of which was to send up an alarm, when necessary, should pirates be spotted off the coast. A small hut was built at the bottom of the cairn to store the combustible materials with which the fire would be lit.

Final Comments

It is a little ironic that there is such a lot to say about a rather small cave, and not a great deal to say about an absolutely enormous cairn on the prow of a hill that dominates the surrounding landscape. It seems clear from the burials in the cave beneath the cairn, dated by association with distinctive artefacts, and supported by stone tools found on the hill, that this was an important location during the Neolithic. It seems likely that the cairn could have belonged to the same period, but it is also possible that it could belong to the following earlier Bronze Age. Further investigation will be required to nail down the date of the site, and to establish if there are any additional structures, such as burial chambers, contained within.

Sources and visiting details are shown in part 1

Gop Cave and Cairn near Prestatyn # 2 – The Neolithic burials

Part 2 – The Neolithic burials in the cave

Introduction

In Part 1 I looked at the excavations carried out at Gop Cave in 1886-7, 1908-14, 1920-21 and 1956-57 and talked about the pre-glacial levels of Gop Cave, with its finds of woolly rhino, hyaena and wild horse, and the Mesolithic tools found outside the cave mouth.

In this second part, the cave is still the topic under discussion, with a shift in focus to the Neolithic layers, whilst the cairn on top of Gop Hill is tackled in part 3. During the Neolithic, the cave was used to deposit a number of burials, two thirds of which were contained within a walled-off section of the cave, and the rest within a narrow passage that linked two parts of the cave. These burials are the subject of this post. References used for all three parts are listed in part 1, together with visiting details.

The Excavations

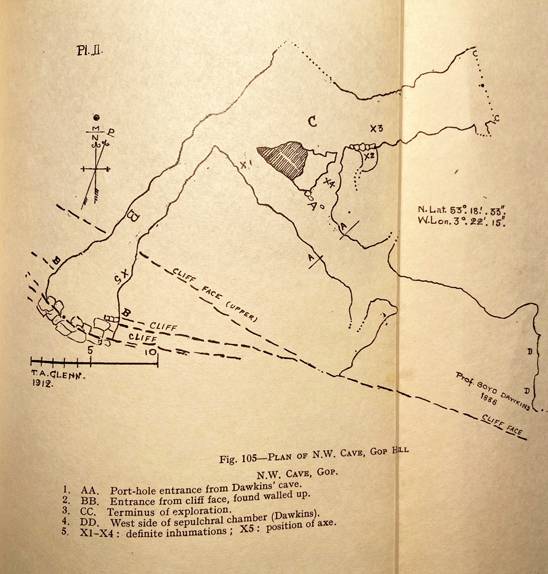

Modern plan of Gop Cave by Cris Ebbs. Source: Cambrian Caving Council Survey 2013

Just to recap briefly on the details from part 1, the earliest excavations in the cave were carried out by Sir William Boyd Dawkins, a well known and respected early archaeologist who excavated the cave site over two seasons in 1887 and 1887, having originally been asked to assess the cairn on top of the hill. The lowest level was barren , but the next contained numerous bones of Pleistocene animals, many of them now extinct. The top two layers contained mainly Neolithic material including human skeletal remains.

In 1908 John H. Morris began digging at the cave, and was joined by T. Allen Glenn, who took systematic notes and made a plan of the newly uncovered sections of the cave. They opened up a passage missed by Boyd Dawkins, referred to as the northwest passage, which linked to a very small opening just to the east of the main cave entrance. During these excavations a further six partial skeletons were found, two of them children. The skeletal remains in both cases were associated with artefacts and animal bones.

Most of the bone collection collected by Boyd Dawkins, and stored in a pigeon house at Gop Farm, were disposed of in 1913 by the tenant of Gop Farm, who threw them down a local mine shaft – which is particularly sad as Glenn had just received permission to take charge of them. Most of the Morris and Glenn finds, both bones and objects, were sent to the National Museum of Wales. Some finds from Gop Cave are also retained by Manchester Museum and Aura Museum Services, and possibly by the Grosvenor Museum in Chester.

The Neolithic burials at Gop Cave

In total, at least 20 individuals were recorded in Gop Cave. The 14 found by Boyd Dawkins and the 6 found by Morris and Glenn may have been deposited at slightly different times, due to the different character of the deposition. Whereas the individuals discovered by Boyd-Dawkins seem to have been buried whole, Glenn is fairly confident that the ones discovered by himself and Morris in a different part of the cave were only partial when they were interred.

Boyd-Dawkins excavations showing the chamber (feature B) above layer 3 and abutting layer 4, which contained skeletal remains of humans with artefacts. Source: Boyd Dawkins 1901. See other cave plans in part 1.

Dawkins describes how he found a thick layer of charcoal over slabs of limestone at a depth of 4ft (c.1.2m) from the surface, which formed an old hearth. Blackened slabs were found throughout the area excavated, and there were also burnt and broken bones of domestic animals and fragments of pottery. “Intermingled with these were a large quantity of human bones of various ages, lying under slabs of limestone, which formed a continuous packing up to the roof. On removing these a rubble wall became visible, regularly built of courses of limestone.” These limestone blocks made up walls on three sides, with the cave wall itself making up the fourth wall, to form a chamber 4ft 6 by 5ft 4 (c.1.4m x 1.65m). Inside the chamber was what Dawkins describes as “a mass of human skeletons of various ages, more than fourteen in number, closely packed together, and obviously interred at successive times.” Individuals were deposited in a crouched position, “with arms and legs drawn together and folded.” His assessment was that the bodies were buried whole. When the chamber became full, another area of the cave was used as an overflow for new burials, identified on the section plan above as area A. Because layer 3 was found beneath the burial chamber, as well as beneath layer 4, Boyd Dawkins concluded that layer 3 had formed a habitation area prior to the burials, in a similar way to two other cave sites in north Wales.

When Morris and Glenn opened up another passage, and found another six individuals, Although the view was confused by rock fall and a very uneven floor, it was thought that limestone slabs may have been used to create a wall around some of the skeletons. Glenn describes the bones as fragmented and partial. Glenn ascribes this to the remains having been brought from somewhere else, rather than having been depleted due to roof fall damage of fragile bones, or the work of the “burrowing animals” that caused disruption in the stratification within the passage. He was methodical and a good observer, so presumably had good grounds for suggesting this, and it is certainly in keeping with other, more recent archaeological evidence for Neolithic burials where partial skeletons are found, apparently due to having died elsewhere and been moved to a particular site for burial. Another possibility is that the body had been excarnated, a practice involving the ceremonial placement of a body in the open air to allow it to be processed naturally so that it was defleshed and partially disarticulated before being collected for interment, which often resulted in the bigger longbones and crania being collected whilst finger and foot bones were left behind.

Having opened the cave out and discovered the second entrance, Morris and Glenn found that it was blocked with limestone slabs, apparently deliberately, although it is by no means certain when this was done. It is not unlike the blocking of entrances to Neolithic burial monuments towards the end of the Neolithic period.

The artefacts associated with the burials

The artefacts associated with both sets of skeletons are all Neolithic in date. Boyd Dawkins assigned them to the Bronze Age on the basis of the pottery, but this has since been re-dated. Both the Boyd Dawkins and the Morris and Glenn excavations produced stone tools, most of which are fairly generic but can be assigned to the Neolithic. One of the Boyd Dawkins discoveries was a long, curved blade, very carefully carved and polished to provide it with smooth surfaces, and showing no signs of usage. He also identified quart pebbles, which he refers to as “luck stones.” Another notable stone tool, this time found by Harris and Glenn in the part of the cave undiscovered by Boyd Dawkins, was a bifacially worked axe head made from Graig Lywyd stone from the well-known Neolithic stone mines at Penmaenmawr, which was apparently unused.

Objects found by Harris and Allen in Gob Cave, including the Graig Lwyd axe at top. Source: Davies 1949.

The pottery was Peterborough ware, and it has been determined that the Gop Cave type was the Mortlake variant of Peterborough ware, which dates to between about 3350 and 2850 BC. All were fragments, and were either grey or black or burnt red.

Pottery found in association with the skeletons by Boyd Dawkins, since identified as Mortlake Ware. Source: Boyd Dawkins 1901

Two unusual items were referred to by Boyd Dawkins as “links,” which he thought were proably used to fasten clothing, and are referred to by some others as belt-sliders. He described them as being made of “jet or Kimmeridge coal,” or “Kimmeridge shale.” As these items are now lost, they cannot be tested (they were last known to be in Manchester Museum, but now cannot be found). He gives the measurements as 54mm L x 22m W and 16mm H; and 70mm L, 22mm W and 27mm H. Boyd Dawkins says that they showed no signs of any usage, and according to Alison Sheriden’s analysis of these object types, this is typical. They appear to have been kept for show rather than being attached to clothing or employed in some other everyday capacity, much like the curved blade and the Graig Lwyd axe head. As jet and Kimmeridge coal come from Yorkshire, and a third of all known sliders have been found in and around Yorkshire, they are certainly exotic goods in northeast Wales, and the rarity of the substance may have endowed it with a particular cachet. Jet has the very unusual property of being electrostatic, so that when it is rubbed it can make one’s hair stand on end! If it was jet, this would certainly have added to its novelty value. 29 of them were known when Sheriden was surveying them in 2012, of which only 6 were certainly of jet, one of which was found in Wales. 12 or 13 were from burial contexts and distribution showed “a marked tendency towards coastal and riverine finds” that are a reminder of the extensive networks that operated in the Neolithic.

Although the objects in the cave are few and far between, some were unused suggesting that they highly valued and retained for special occasions or as prestige items. It is unclear whether any artefacts were associated with any particular individuals, although Boyd-Dawkins describes the the jet sliders and the polished flint flake forming one group together.

Animal remains

Although he does not list numbers, Boyd Dawkins says that the remains of the domesticated species “were greatly in excess of those of the wild animals, and the most abundant were those of sheep.” He also comments that the horse listed under wild fauna may actually be domesticated, and that foxes were using the vicinity of the cave area at the time of the excavation. All bones were found in what he describes as “prehistoric refuse heaps and that nearly all were broken and burnt.

As all the bones were discarded in 1913, none of the identifications can be checked, but Boyd Dawkins was very experienced in the identification of animal remains, giving some confidence that his work reflected the reality of the situation. Sheep and goat are notoriously difficult to tell part, so the question-mark against goat is not surprising. That sheep are dominant is not a surprise, as the area around Gop would be ideal grazing for them. The valley bottom would have been well-suited for cattle and horse.

Dating the skeletons

Although the artefacts found in the cave, loosely associated with the skeletal remains, are indicators of a mid-Neolithic date, as described above, in 2020 Rick Schulting was able to pull together 23 samples from a number of caves for radiocarbon dating, including three samples from Gop Cave, comprising two mandibles and one cranium. Although some samples had been tested previously, an error in the sampling method had led to them being withdrawn in 2007. For Gop, the new dates lie firmly with the Middle-Late Neolithic range, tending towards the middle of the Neolithic (between c.3100 and 2900 BC).

This date range backs up the findings of the Mortlake variants of the Peterborough ware, the jet sliders and the Graig Lwyd axe.

The practice of non-monumental burials

The main form of burial recognized throughout most of the Neolithic Britain is the long barrow or cairn, or the round passage grave. In each case, there was usually an accumulation of burials over time, referred to as collective burials. These were not, however, the only forms of burial during the Neolithic. Although less often found, because of the lack of monumental marker, flat interment cemeteries are known, burials in the ditches of the so-called causewayed enclosures are often recorded and there is some, uncertain data that there may have been burials in rivers. During the later Neolithic, cremation became the norm.

By far the most common non-monumental form of burial, however, is deposition within a cave. Cave burials of various dates are known from all over Britain. In his survey of cave burials in 2020, Rick Schulting noted examples from the Palaeolithic through to the Anglo-Saxon period. From the Neolithic in north Wales, contemporary with Gop Cave, nearby Nanty-Fuach rock shelter above Dyserth produced five burials, all contracted, and without grave goods. Outside the cave there were fragments of Neolithic pottery, a large barbed and tanged arrowhead and, nearby, some Peterborough ware. In the Alyn valley 16 burials were deposited within Perthi Cawarae, and 6 within Rhos Ddigre, the latter associated with a Graig Lwyd axe and pottery fragments, both in the Alyn valley. Other examples are known from Loggerheads and Mostyn with Neolithic flint implements. It is clear that Gop Cave is by no means an isolated example, although the precise arrangement of the skeletal remains within containing walls may be unusual. As many caves were excavated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when excavations lacked today’s precision, it is impossible to know what was missed by excavators. Finally, Schulting notes that there is a gap of “several millennia” between the last Mesolithic cave burial and the first Neolithic ones, indicating that there is no continuity of burial tradition in caves between the two periods.

Meaning in collective burial

Frances Lynch suggests that the use of caves for burial, occurring in many areas at different periods “seems to be a matter of convenience rather than cultural preference” but there are alternative views on the matter. In his book on the materiality of stone – Christopher Tilley does not discuss caves, but he references almost every other aspect of stone as a natural material that becomes objectified by human uses and actions. He comments that social identity requires “specific concrete material points of reference in the form of landscapes, places, artefacts and other persons.” Topographic and other natural features are often used by humans to anchor and fix memory and establish places of meaning in landscapes. Carole Crumley highlights the phenomenological experience of features like caves, mountains and springs, and their role in connecting the mental with the material to create both individual and social identity. In their chapter on the uses of landscape features like caves and springs by the Maya in Mesoamerica, James Brady and Wendy Ashmore describe how caves, eternally damp and dripping water, were connected with the sacred and the ritualization of water. By appropriating and modifying such natural features, people have embedded them with meaning to form bridges between the natural, supernatural and the manufactured, blurring the differences to confer special status on these dark places where the dead might be deposited safely.

Frances Lynch suggests that the use of caves for burial, occurring in many areas at different periods “seems to be a matter of convenience rather than cultural preference” but there are alternative views on the matter. In his book on the materiality of stone – Christopher Tilley does not discuss caves, but he references almost every other aspect of stone as a natural material that becomes objectified by human uses and actions. He comments that social identity requires “specific concrete material points of reference in the form of landscapes, places, artefacts and other persons.” Topographic and other natural features are often used by humans to anchor and fix memory and establish places of meaning in landscapes. Carole Crumley highlights the phenomenological experience of features like caves, mountains and springs, and their role in connecting the mental with the material to create both individual and social identity. In their chapter on the uses of landscape features like caves and springs by the Maya in Mesoamerica, James Brady and Wendy Ashmore describe how caves, eternally damp and dripping water, were connected with the sacred and the ritualization of water. By appropriating and modifying such natural features, people have embedded them with meaning to form bridges between the natural, supernatural and the manufactured, blurring the differences to confer special status on these dark places where the dead might be deposited safely.

Artist’s impression of what an excarnation platform might look like. By Jan Dunbar. Source: BBC

A number of authors have suggested that collective burial of humans, and in particular the mingling of bones rather than maintaining skeletons as delineated individuals, is an indication of the individual being subsumed into a collective identity, privileging the group identity over the authority or status of any one individual. Of course, these collective burials, whether in monument or cave, are representatives of much larger communities, and the criteria used for selecting one person for burial over another are lost. It is possible that in order to transform an individual into a representative of the community, a two-stage process was undertaken whereby an individual is excarnated or buried elsewhere, and then moved to a collective burial site, a transformative process during which the individual member of the community loses their individuality and becomes representative of a communal and ancestral link between the past and the present. With the addition of each new individual to the cemetery, another layer of communal meaning was added to the cave, reinforcing the message that the existing burials already encapsulated.

In the contrast between the brightness of the light-coloured limestone reflecting in the sun, and the darkness of the hidden, secret interior there is a resemblance between the relationship between the visually striking chambered tomb and the sepulchre within. Not forgetting, of course, that there is an enormous cairn on top of the hill, just 43m (141ft) away from the cave, which may in itself have been a marker rather than a grave. The cairn is discussed in part 3.

In the contrast between the brightness of the light-coloured limestone reflecting in the sun, and the darkness of the hidden, secret interior there is a resemblance between the relationship between the visually striking chambered tomb and the sepulchre within. Not forgetting, of course, that there is an enormous cairn on top of the hill, just 43m (141ft) away from the cave, which may in itself have been a marker rather than a grave. The cairn is discussed in part 3.

Final Comments

Gop Cave is often left out of accounts of the Neolithic in Wales, or merely mentioned in passing, which is surprising given both the number of its human occupants and the unusual combination of artefacts found within the cave. Cave burials are given secondary status to monumental constructions, but given the number of them in Wales, it is good to see that they are now being researched as valid contributors to the corpus of knowledge about the Neolithic both in Wales and the rest of Britain.

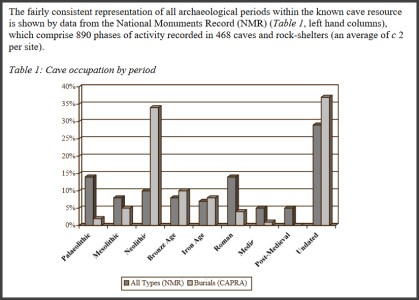

Graph from Jonathan Last showing the usage of caves at different periods in England (The Archaeology of English Caves and Rock-Shelters: A Strategy Document. Centre for Archaeology Report 2003)

Sources and visiting details are in part 1

Gop Cave and Gop Cairn near Prestatyn – # 1: Woolly rhinos and hungry hyaenas

Introduction

Gop Hill in northeast Wales, a few miles southeast of Prestatyn, and just above the village of Trelawnyd (formerly Newmarket from 1710 to 1954) is home to Gop Cave and Gop Cairn, just a few minutes apart from one another. Gop Cairn has the distinction of being the largest man-made prehistoric mound in Wales, and when approached from a distance, its size really is impressive. Although the cairn was investigated in the 19th century, with a vertical shaft sunk from the top to the level of the floor, and a “drift” tunnelled outward from the base of the shaft, no burial chamber or human remains were found.