xx

Eaton Hall is part of the Duke of Westminster’s estate 4.2miles / 6.7km to the south of Chester. It was very common for wealthy families to feature ancient Egyptian and Roman objects on their estates from the 18th century onwards. Many of these were imported from overseas, but the cobbled-together display of a Roman altar in a small custom-built structure, flanked by two columns, are thought to have come from no further afield than Boughton, on the eastern outskirts of Chester, Roman Deva.

The gardens are only open to the public for three days a year for charity, and tickets tend to sell out very quickly, so this is not the easiest of the local Roman monumental works to visit, although others are on display in the Grosvenor Museum in Chester.

The Roman army had arrived in Chester, Deva, in around AD 74 and, with a requirement for a base on the Anglo-Welsh border area, settled on Chester as a suitable and obvious location. The river Dee had connections both south towards Wales and northeast via the Dee estuary to the sea, and was defensible. An earlier Iron Age settlement found during excavations at the Roman amphitheatre indicate that the Roman incomers were not the first to appreciate this location. The first fortress, built in around AD 76, was an earthen bank with a wooden palisade, gateways and interval towers, only being converted to stone from c.AD 100. As it grew, the new army base included the usual architectural and administrative collection of a headquarter building, officers’ accommodation, barracks, baths and storage, as well as the elite and unique ‘elliptical building’. Most of the stone for the new town was quarried locally from red sandstone bedrock, at least some of it derived from Edgar’s Field, on the south bank of the Dee at Handbridge, where a shrine to the goddess Minerva, protector of craftsmen, was carved directly into a red sandstone outcrop. Beyond the walls were a parade ground, the amphitheatre to its south and, eventually, a civilian settlement (canabae legionis), which inevitably grew up to take advantage of the new population.

It is probable that the altars and tombstones were made by indigenous craftsmen who came to these settlements to take advantage of the disposable income available from both the residents of the Roman town and their fellow settlers.

Julian Baum’s wonderfully evocative reconstruction of the fortress at Chester and the outer buildings in the mid 3rd Century, with the road leading away from the amphitheatre towards the bottom right, heading out east towards Boughton (copyright Julian Baum, used with permission)

Altars, demonstrating piety towards a particular deity or spirit, could be purchased by Roman citizens for personal worship, or could be donated to public areas. A specific request for help would be based on a deity’s particular skillset or virtues. Gods and spirits of place all had different characteristics and were associated with specific roles and functions. Sometimes altars were offered in hope of good fortune or as thanks, a form of obligation in return for a certain request being granted. Rituals accompanied by offerings took place at such altars to appeal to, appease, or thank a given deity. Such altars expressed a relationship between whoever erected the altar (a person, family or community), and the deity whose influence had been requested.

Inscriptions carved in Latin onto Chester altars and gravestones have provided considerable information about their owners and the wide range of places from where those owners originated, as well as providing insights about the deities that their purchasers had considered most relevant and helpful to their personal hopes and ambitions, both in life and the afterlife.

Inscriptions carved in Latin onto Chester altars and gravestones have provided considerable information about their owners and the wide range of places from where those owners originated, as well as providing insights about the deities that their purchasers had considered most relevant and helpful to their personal hopes and ambitions, both in life and the afterlife.

All known Roman inscriptions are recorded on the Roman Inscriptions of Britain website (https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/about/about-rib-online) itself based on the earlier printed volumes. The information about the altar in this short article comes from the Roman Inscriptions of Britain website. The official designation of the Boughton altar on the Roman Inscriptions of Britain website is RIB 460, and is classified as a “private possession.” The altar was found in 1821 in a field at the north end of what is now Cherry Road, near Boughton Cross, and about 1.8km east of The Cross, in Chester.

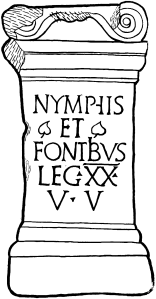

The altar is just under 120cm tall, 61cm wide and 50m deep. It is undated. There is an inscription on the front and back, but nothing on the sides. It stands on a pedestal, also original. The front is slightly damaged, but the front and back both read

Nymphis

et

Fontibus

leg(io) XX

V(aleria) V(ictrix)

Illustration of the RIB 460 inscription. Source: Roman Inscriptions in Britain.

The Roman translation, as provided by the Roman Inscriptions of Britain page reads: To the Nymphs and Fountains the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix. In other words, the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix set this up to the nymphs and fountains. It seems probable that the altar was built to commemorate guardians of the natural springs in the Boughton area, which probably supplied Deva with its water. The Romans had a particular affinity with natural springs, and often dedicated monuments to them. The best known in Britain is the dedication to Sulis-Minerva at the Roman baths in Bath, Sulis being the indigenous deity with whom the Roman Minerva was associated. The Eaton hall altar was not dedicated to a particular deity, simply venerating the more ephemeral but equally important and much-valued spirits of the place.

The springs in Boughton, 1.5km (1 mile) east of the city, which were fed by an aquifer sealed between two layers of boulder clay, were delivered to Chester by an aqueduct and pipes. One route entered Chester along the line of Foregate Street and the other ran to its south, feeding the cisterns for the bath-house boilers near the southeast corner of the fortress. David Mason estimates that in a 24 hour period, the military consumed some 2.370,000 litres (521,337 gallons) of water.

The Boughton altar is now housed in a structure referred to as “the loggia,” located in an open grassy area lying between the formal gardens, and is roofed and open-fronted. It was presumably designed to loosely emulate a very small Roman temple. Two original Roman columns flank the loggia and, within it and protected from the outside world by railings, is a Roman altar made of red sandstone. The loggia protects the altar from the elements, and it appears to be in relatively good condition.

Although the Eaton Hall altar is not the easiest to visit, there are some excellent examples of both altars and gravestones in the Grosvenor Museum in Chester, which can be visited throughout the year.

Sources:

Books and Papers

Carrington, Peter 1994. The English Heritage Book of Chester. Batsford / English Heritage

Mason, David, J.P. 2001, 2007 (2nd edition). Roman Chester. City of the Eagles. Tempus Publishing

Websites

Based in Churton

An impressive exhibit of decorated Roman tombstones in Chester’s Grosvenor Museum

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/2022/07/04/an-impressive-exhibit-of-decorated-roman-tombstones-in-chesters-grosvenor-museum/

Eaton Hall Gardens Charity Open Days 2022

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/2022/06/28/eaton-hall-gardens-charity-open-days-2022/

Grosvenor Museum

https://grosvenormuseum.westcheshiremuseums.co.uk/

Roman Inscriptions In Britain

RIB 460 (Eaton Hall)

https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/460