Not for the first time I am writing about somewhere that I really ought to have talked about a long time ago because it is so near to me, in this case the Grade II* listed St Chad’s Church just down the road in Farndon. It is a lovely church, with a rather unexpected history, surrounded by a churchyard and enclosed by an irregularly shaped curving wall. Apart from the tower, there is very little of the medieval church remaining, having been almost completely rebuilt in 1658 following the damage inflicted during the Civil War, but it followed a broadly gothic template and is charming in its own right with a number of nice features, some influenced by the gothic, and others departing in interesting directions. It is particularly well known for the Civil War window installed by William Barnston.

The congregation traditionally included those who were on the English side of the river, with burials from Churton-by-Farndon and Churton-by-Aldford, Crewe-by-Farndon, Barton, Leche, and Caldecott, and other nearby villages and farms. After 1866 residents of Churton-by-Aldford were often buried in at the Church of St John in Aldford.

During the summer I posted an account of St Chad’s Church in Holt, opposite Farndon on the other side of the river Dee, with its medieval links to Holt Castle and the Lordship of Bromfield and Yale. It is larger and more elaborate than St Chad’s in Farndon, and the two churches each has its own distinctive character with a lot to offer the visitor. Both churches were involved in the Civil War, due to the importance of the crossing here, and both bear musket ball damage as a result, but Farndon’s St Chad’s came off much worse than St Chad’s in Holt.

xxxxxx

Saint Chad, 1st Bishop of Lichfield

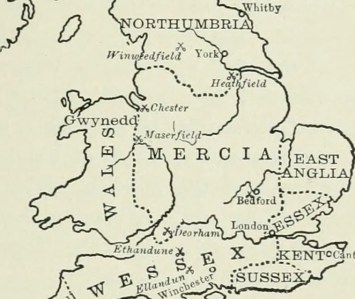

Early Medieval Mercia. Source: medievalists.net

According to Bede (writing in the 8th century) St Chad was one of four brothers who entered the church in the 7th century, and started his training at Lindisfarne Monastery under St Aiden. He was ordained in Ireland and became a leading light in the Anglo-Saxon church, rising through the ecclesiastical ranks on the kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia and under King Wulfhere, one of the earliest Christian kings. He was appointed Bishop of Northumbria, including York, and became the first Bishop of Lichfield in the new diocese of Lichfield, at the heart of Mercia. Mercia was one of seven British kingdoms of 7th century Britain and occupied most of central England. Chad died in AD c.672 and was buried in Lichfield Monastery, now Lichfield Cathedral. Regarded as a pioneer who helped to spread Christian teaching in and beyond Mercia, he became a popular icon during the Middle Ages in the Midlands and its borders.

xxx

The Medieval Church

It is remarkable to think that the Civil War obliterated so much of the medieval church in 1643 that most of it had to be rebuilt in the 17th century. The Domesday book records a village priest, as well as two other priests locally, strongly suggesting the presence here of an earlier church, probably wood-built.

Today’s church has a nave and tower that are thought to have followed the original medieval footprint dating to the14th century building. All that obviously remains of the 14th century is the tower, of which three storeys date to around 1343. Everything else appended to this basic structure on north, east and south sides are later in date. Although you enter the church through an 18th century yellow sandstone porch, the thick wooden door itself is actually medieval, a quite astonishing survival.

Inside, looking towards the tower from the nave, you can see the converging lines at which the old church roof met the tower, considerably lower down than the current roof, and terminating further down than the current arch. This suggests that the medieval church was both shorter and darker. Within the tower there are three chambers with one each for bell-ringers, another for the clock-works and the belfry itself, containing the bells, originally three, at the top.

In the north aisle in the interior of the church is a 14th century funerary effigy showing a knight in armour holding a shield carved with a Latin inscription reading “Here lies Patrick of Barton. Pray for Him.” Sir Patrick holds a sword in his other hand, and has some form of animal at his feet, now too badly worn to be identified with any certainty. This effigy is one of three that was found, but the other two were ground down to make white sand. Although Sir Patrick survived this particular indignity, he was used as a step into the belfry in in the 1900s, which accounts for the wear and tear to his face and the animal. Latham says that one of the other effigies was inscribed with the word “Madocusdaur” and a third was inscribed with a wolf.

John Speed, Tailor and Mapmaker

John Speed’s 1610 map of Cheshire. Source: Wikimedia Commons

John speed was the Farndon tailor’s son and was baptised in St Chad’s in 1552. There’s a good biography of him on the New World Cartographic website explaining how Speed followed his father into tailoring at a time when fashion was of growing importance, doing very well in the business, whilst at the same time pursuing his interests in history, geography, cartography, antiquities and genealogies. It was not until he moved to London that he gained a patron and was able to abandon tailoring and launch a new career. His map of the County of the Palatine of Chester was completed in 1610-11, and was used by both sides during the Civil War. He died in 1629 and is buried in London.

xxx

The Civil War

The tower in Farndon’s church shows musket-ball and cannon shot damage to the exterior, to the right of the main porch, but the fact that the rest of the church had to be rebuilt in 1658 makes it clear that it experienced a much worse time of it than its counterpart in Holt. In 1643 the commander of the Cheshire and Lancashire Parliamentarian troops used Farndon and its church as a headquarters and barracks, assembling a force of around 2000 to force their way across the bridge, through Royalist defences. The subsequent fighting entered the churchyards at both Holt and Farndon. During the fighting in Farndon churchyard the roof was somehow set alight. In spite of the damage to the roof, the Parliamentarians reoccupied the church until they were ousted in winter 1645.

xxx

The 17th Century Rebuild

Apart from the tower at the west end, the current red sandstone church with its slate-tiled roof is largely the result of the post-Civil War rebuild in 1658, presumably re-using some of the original medieval stonework. The main body of the church consists of a nave with clerestories (a run of windows above the nave below roof level to allow in light) and two aisles, terminating in the chancel at the east end. The 5-bay arcade separating the nave from the aisles consists of round piers (columns) with simple capitals and pointed arches. Over 40 different mason marks are dotted throughout the church, each one identifying a separate mason, giving a hint of the scale of the workforce required to rebuild St Chad’s. There used to be a musician’s gallery at the tower end, but this was removed in the 19th century.

Apart from the tower at the west end, the current red sandstone church with its slate-tiled roof is largely the result of the post-Civil War rebuild in 1658, presumably re-using some of the original medieval stonework. The main body of the church consists of a nave with clerestories (a run of windows above the nave below roof level to allow in light) and two aisles, terminating in the chancel at the east end. The 5-bay arcade separating the nave from the aisles consists of round piers (columns) with simple capitals and pointed arches. Over 40 different mason marks are dotted throughout the church, each one identifying a separate mason, giving a hint of the scale of the workforce required to rebuild St Chad’s. There used to be a musician’s gallery at the tower end, but this was removed in the 19th century.

The nave of the 1658 nave, arcade and overhead clerestory. The entrance to the Barnston chapel is shown at lower far right.

The new church was taller than the old one, with the clerestory and the large Gothic-style lancet windows letting in much more light. The tower was provided with a new top section at this time.

Adding to the footprint of the old church, the Barnston family, major landowners in the area, built a small chapel off the chancel end of the south aisle, for their private use and to bury and commemorate family members. According to the church’s history booklet, there are records mentioning Barnstons in Churton during the reign of Henry VI in the 15th century. In the 17th century William Barnston was a major contributor to the rebuild of the church, and requested that he be buried under a gravestone in the south aisle of the church that has already been placed ready. His 1663 will left a substantial bequest to the church for its upkeep. He died in 1664.

An adviser to Charles I at the Siege of Chester, William Barnston was responsible for the famous Civil War window in the chapel. What surprises most people who see it for the first time is how small it is, but it is full of details that show Royalist participants, including Barnston himself, and a variety of items of contemporary clothing and equipment used in the Siege of Chester. Pevsner and Hubbard say that the technique is “decidedly Dutch” and Latham adds that “Its artist took his design for the armour from a military work by Thomas Cookson (1591-1636) and for the bottom border from prints by Abraham Bosse (1632).” My photo, left, is very poor due to the lack of light, but have a look at the Visit Stained Glass website for a much better image and a close-up of the depiction of William Barnston.

There are many features of interest to look out for in the 17th century church. In the south aisle there is a rather fine sculpted wooden beam support. The church’s booklet questions whether it is a human or an animal but it looks very like the lions with curly manes that are familiar from Tudor and Jacobean carvings. It is surprising that it is on its own. The damaged medieval font was repaired by Samuel Woolley of Churton but the current octagonal font is thought to date to 1662, replacing the repaired one.

XXXxxx

18th, 19th and early 20th century alterations

According to Frank Latham, by 1735 “St. Chad was surrounded by green fields and the houses were few and far between,” and the Massie family seems to have been important to the congregation at this time, with six pews allocated to Richard Massie Esq., and his family. He adds that the east wall was demolished in the 18th century and shifted 10ft (c.3m) further to the east, providing a much larger chancel. Towards the end of the century repairs to the roof were made between 1793 and 1798. Today the red sandstone church is entered via a Georgian-style porch built in yellow sandstone, although I have seen no mention of a precise date for this, and inside there is a large 18th century oak chest that housed the church plate and the parish records.

The eastern end of the church was remodelled to include today’s chancel in 1853, not by the Barnstons this time but by the Marquess of Westminster. The carved reredos behind the altar shows the Last Supper and was installed in 1910, with the carvings on the pulpit were added in 1911, showing St Chad accompanied by the usual pulpit team of Saints Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, represented by their emblems. In 1927 the original three bells were joined by another five. The church booklet says that they were rung to mark nationally important occasions, including the defeat of Napoleon in Egypt in 1799, and his defeat at Trafalgar in 1805.

Of the various memorials, one that may be of interest to those familiar with the Barnston obelisk just outside Farndon, is the marble memorial to the Major Roger Barnston (died 1847) in the Barnston chapel. The obelisk in the field on Churton Road, now a natural burial ground, is also a memorial to Major Barnston (died 1847) discussed on the blog here,

The north aisle, like nearly all churches in this area, used to have a clear run to the end of the nave, but the presence of an organ since the 19th century regrettably meant that a gallery just in front of the tower’s arch, where musicians located, became redundant and was removed. The present organ dates to 1949.

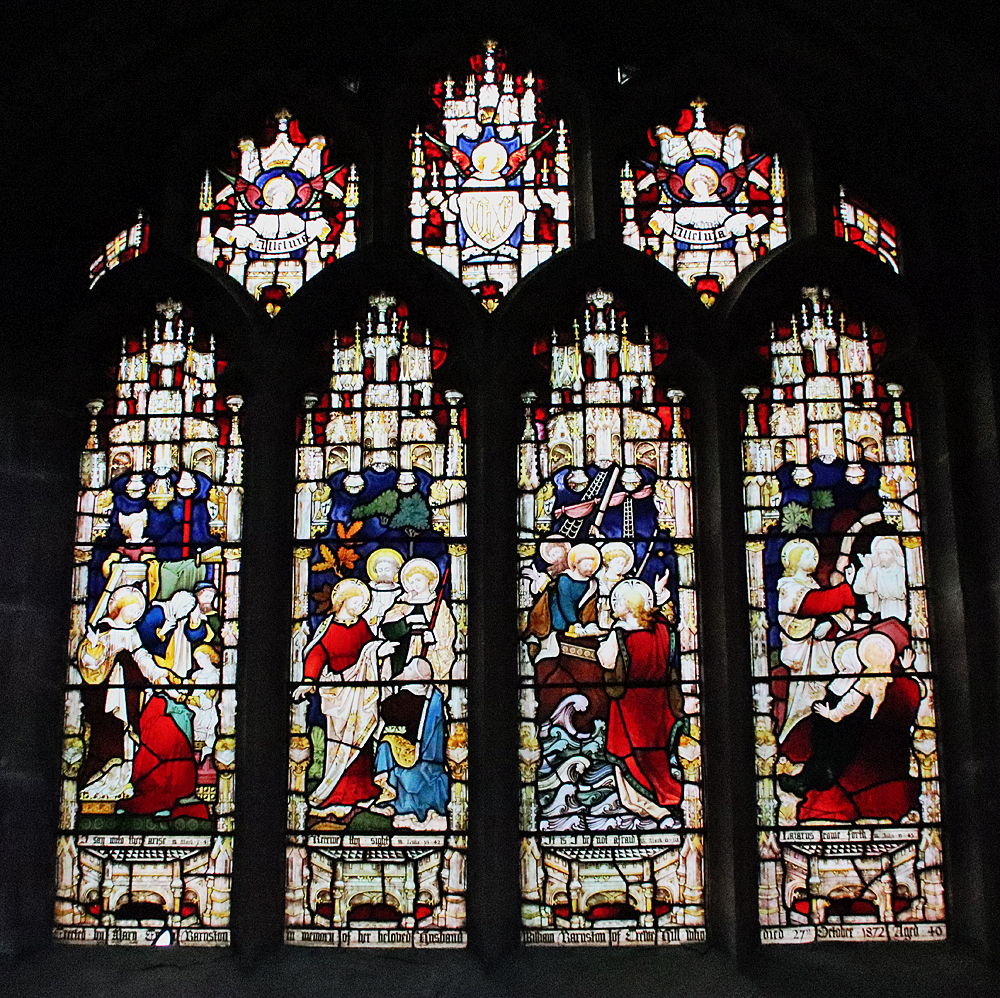

The windows are often round-topped, set within rectangular frames that give the exterior an unusual appearance. Exceptions are the large east window behind the altar, installed in 1858 and showing the Sermon on the Mount, installed in memory of church benefactors William and Anne Plumpton, and the south window in the Barnston chapel, both gothic-style.

Most of the stained glass is interesting for the contrasting styles. Following the Trena Cox: Relections 100 exhibition in Chester last year I have become quite interested in 19th century stained glass. On the north side of the chancel, to the left as you face the altar, is a window showing St Chad and St Werburgh (to whom Chester Cathedral was dedicated when it was a Benedictine monastery), by Trena Cox. A look at Aleta Doran’s website devoted to Trena Cox confirmed that this was one of hers, from the 1950s (1953 to be exact). Those windows immediately opposite are similar in style but were clearly crafted by a different artist and show St David (patron saint of Wales) and St Cecilia. Most of the other stained glass was added in the 19th century, with many of the larger window openings being decorated with romantic takes on the gothic, whilst smaller ones are more minimalist. It was a little sad not to be able to learn something about the makers of the glass either at the church or after a hunt through my books and around the Internet.

Window dedicated to the memory of Harry Barnston installed by his sisters after he died in 1929, in somewhat Pre-Raphaelite style

At the rear (south side) of the building you can see a substantial addition at the west end (near the tower) and I assume that this was a 20th or 21st century add-on, presumably acting as a vestry and storage.

xxx

The Churchyard

The churchyard includes a mixture of different types of grave, including chest, table and ledger tombs and vertical headstones, some accompanied by kerbs, mainly of good quality yellow sandstone. A particularly fine example is a Grade II listed double-chest grave made of yellow sandstone and dating to the early 18th century :

West ends of tombs have recessed round-headed panels; that to north contains an hourglass, that to south a skull and crossbones above an inscription Mors S… Omnium [i.e. Mors Sola Omnia,” meaning Death Conquers All]. North side of north tomb has a square central panel containing an encircled quatrefoil in a lozenge with a vertical panel right and a decayed panel left. The east end of each tomb has a fielded panel; south side of south tomb has 3 fielded panels in bolection moulded borders (Historic England – list entry number 1228746)

West ends of tombs have recessed round-headed panels; that to north contains an hourglass, that to south a skull and crossbones above an inscription Mors S… Omnium [i.e. Mors Sola Omnia,” meaning Death Conquers All]. North side of north tomb has a square central panel containing an encircled quatrefoil in a lozenge with a vertical panel right and a decayed panel left. The east end of each tomb has a fielded panel; south side of south tomb has 3 fielded panels in bolection moulded borders (Historic England – list entry number 1228746)

It was sobering to notice just how many of the chest grave inscriptions commemorate infants and children. I always spend an hour or so reading grave inscriptions and don’t remember seeing so many very young children commemorated, often from the same family in the same generation. As you would expect, the earlier graves are nearest to the church, although unusually many of these are on the north side, which is normally the last to be filled.

Moving away from the immediate area surrounding church building, to its south, the traditional upright gravestones of the later 19th century begin to dominate, with many examples of 19th century funerary symbolism on the headstones. Although many of the headstones are lancet-shaped and much of a muchness in terms of size, there was clearly a lot of choice available in terms of the symbolic motifs that decorated the tops of the graves.

Through a small gate beyond the headstones, the churchyard has been extended for modern use. The 1922 War Memorial in the form of a stone cross commemorates eighteen men killed in the First World War and four in the Second World War.

xxx

Final Comments

This medieval church, almost completely rebuilt in the 17th century, has a character of its own, reflecting various periods of restoration and intended improvement, with a strong gothic influence throughout. There are many more features than those described above, including benefaction boards, a list of incumbents, and memorials, and the church booklet produced by Cheshire County Council in 1989 is a good guide.

This medieval church, almost completely rebuilt in the 17th century, has a character of its own, reflecting various periods of restoration and intended improvement, with a strong gothic influence throughout. There are many more features than those described above, including benefaction boards, a list of incumbents, and memorials, and the church booklet produced by Cheshire County Council in 1989 is a good guide.

The church website contains no information about visiting, and the Facebook page hasn’t been updated since 2019, but at the moment the church has an open door policy. On my two recent visits (October 2025) I was able to walk in. There is a contact page on the site, so if you are coming from any distance it might be worth double-checking.

It is splendid to have two really impressive churches, one either side of the river connected by a splendid 14th century bridge, with very different personalities and features, and both very well cared for and open to visit.

Sources:

Books and papers

Cheshire County Council 1989. The Parish church of St Chad, Farndon. (10-page booklet available for purchase at the church)

Cheshire County Council 1989. The Parish church of St Chad, Farndon. (10-page booklet available for purchase at the church)

Latham, Frank 1981. Farndon. Local History Group

Pevsner, Nikolaus and Edward Hubbard 1971. The Buildings of England: Cheshire. Penguin Books

Websites

Based In Churton

Medieval ambition and Civil War musket ball holes at the Church of St Chad’s in Holt (Grade 1 listed)

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/2025/05/31/medieval-ambition-and-musket-ball-holes-at-the-church-of-st-chads-in-holt-grade-1-listed/

Exhibition in Chester Cathedral: “Trena Cox: Reflections 100”

https://basedinchurton.co.uk/2024/10/19/exhibition-in-chester-cathedral-trena-cox-reflections-100/

Historic England

Pair of Adjacent Table Tombs in Churchyard

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1228746?section=official-list-entry

New World Cartographic

Map Maker Biography: John Speed (1552 – 1629)

https://nwcartographic.com/blogs/essays-articles/map-maker-biography-john-speed-1542-1629

St Chad’s Farndon

https://www.stchadschurchfarndon.org.uk/index.php

The Trena Cox Project

https://www.aletadoran.co.uk/

Visit Stained Glass

St Chad’s Farndon (just the Civil War window)

https://www.visitstainedglass.uk/location/church-of-st-chad-farndon-cheshire

Ancient Churchyards of Cheshire – St Chad’s Church Farndon

Tvpresenter4history (James Balme)