The portico dates from 1997, but the original Neo-Georgian military Western Command building can be seen behind it.

With many thanks to Chantal Bradburn for an excellent lecture in the Churchill Building in the University of Chester’s Queen’s Campus. Chantal is the University’s Outreach representative, with a strong background in art history and a particular interest in architecture in its social context. Her talk, entitled “Western Command (Churchill Building),” covered the design and original purpose of the building as the headquarters of the Western Command, including the fascinating underground bunkers, and the building’s subsequent phases of use. The presentation and the subsequent walk around the building’s exterior brought the Western Command to life. Chantal’s ability to convey an impression of the building as it was in military times, based partly on her research and partly on feedback from people who have attended the talk or contacted her over the years, was of critical importance, because the interior had been completely re-envisioned in grandiose style by the subsequent bank, and converted once again in more pragmatic terms into the University of Chester’s Business School. Only the exterior retains the essential character of the Western Command building.

The eastern wing of the Western Command (Churchill Building) gives a good impression of how the building appeared when it was first built

The building, then known as Capital House, was completed in around 1938, almost certainly in response to the threat of war. Neo-Georgian is not my favourite of the various architectural experiments in Chester. I have grumbled on and off about the Wheeler Building on the blog for years, and there are a number of more modest buildings dotting the streets of the historic city whose architects seem to believe that slapping some symmetrical rectangular windows into plain blocks of undifferentiated brickwork will do the trick nicely, completely missing the point of refined elegance and delicate embellishments that characterized Georgian harmonies. On the other hand, as Chantal pointed out, at least in the case of the Churchill Building there are good reasons for this style, which is better than most of its siblings, relating not merely to the practicalities of budget constraints for such a large building.

The importance of establishing a dignified military presence referenced the power and prestige of the city’s Georgian predecessors, which were themselves influenced by Classical architecture, whilst some low-key features nod to both the medieval military past and, in an even more subtle way, other contemporary styles. I would not have noticed these had Chantal not pointed them out. Although the subsequent Northwest Securities bank slapped a gigantic Classical-style portico on the front, the original building consisted of flat-roofed blocks that provided an impressive frontage, which relies for its impact on the size of its footprint rather than the height of its two-storey walls. Chantal pointed out that the position of the building was strategically very fine, with its views over the river and the city beyond, only matched in its vantage points by the site chosen for the castle.

As the northwest HQ for intelligence on what was quite literally Britain’s western front during the war, the personnel serving in the Western Command building had a critical role not only leading up to and during the war, but for a surprising amount of time after it. Chantal told us a great many stories about the role of the building and the people who worked there, highlighting the complexities that different levels of security caused for both employees and contractors, and emphasizing the degree of secrecy that was associated with the activities that took place within the Churchill Building.

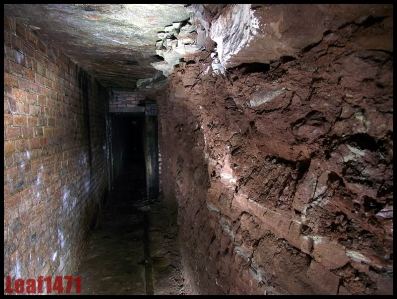

Bunkers excavated into the sandstone at the Churchill Building. Source: 28DaysLater

To the east of the building, up-river, the remarkable and extensive underground bunkers were built to provide shelter and a command centre should it become necessary, both during and after the Second World War. They extend from the level of the building down towards the river. It is reputed that Churchill, who is known to have visited the building, may have met there with President Dwight D. Eisenhower and General Charles de Gaulle. No documentation supports this view, but there are apparently anecdotal accounts that support the possibility. The bunkers are now too dangerous to visit (see a photograph of a point of collapse on the 28DaysLater website). The sandstone through which former miners in the army excavated to create the bunkers is sponge-like, attracting damp that is not helping with the stability of the underground structures. Chantal showed photographs and explained past survey work and future plans (dependent as always on funding).

The building passed to the Royal Army Pay Corps in 1972, and from 1972 it was taken over as offices for a banking corporation. The presentation took place in a huge room with an enormous table, all very glossy and highly polished, and heavily influence by Art Deco designs. This was part of the bank’s improbable legacy. It is quite staggering how the bank took over a military building and turned it into an extrovert and financially corrosive expression of self-indulgent excess. Where these details have survived, the legacy is huge fun, but quite mad. The bank’s vast portico, converting the Neo-Georgian blocks into a pseudo Classical temple, is equally pretentious. I am very fond of the University, having had a great time doing some post-graduate research there a couple of years back, but it really does seem to have saddled itself with buildings that for all their scale and practicality are amongst the least aesthetically charming of the various Cestrian styles. In their favour, the University does make the most of them.

The building passed to the Royal Army Pay Corps in 1972, and from 1972 it was taken over as offices for a banking corporation. The presentation took place in a huge room with an enormous table, all very glossy and highly polished, and heavily influence by Art Deco designs. This was part of the bank’s improbable legacy. It is quite staggering how the bank took over a military building and turned it into an extrovert and financially corrosive expression of self-indulgent excess. Where these details have survived, the legacy is huge fun, but quite mad. The bank’s vast portico, converting the Neo-Georgian blocks into a pseudo Classical temple, is equally pretentious. I am very fond of the University, having had a great time doing some post-graduate research there a couple of years back, but it really does seem to have saddled itself with buildings that for all their scale and practicality are amongst the least aesthetically charming of the various Cestrian styles. In their favour, the University does make the most of them.

The opening of the Churchill Building by John Spencer Churchill (centre in grey suit), when it became part of the University of Chester in October 2015. Source: Cheshire Live

It is interesting to note that in the case of both military base and commercial bank, the building was off-limits to the public, not only physically but visually. The arrangement of buildings at the time meant that the view through the gates, then in a different position, blocked any view of the heart of the complex. It has been particularly interesting for local people who have lived in the area for a number of decades to have access to the building at last, and to be able to see what was so long hidden from view, perhaps particularly when family members and friends worked there.

The building had been out of use for a decade when the University took it over in 2015 to make it the centre for their Business School, with most of the building adapted to this task with the usual collection of teaching, research and computer rooms, areas for socializing and a café. Wisely, the decision was made to preserve some of the more elaborate flourishes of the bank’s idea of good taste, and there are some distinctly New York style decorative features in the foyer. More to the point, the building’s foundation stone and its frame, appropriately made of carved stone rather than the less expensive brick, has been preserved and is now installed above the reception desk as a very welcome piece of the building’s material heritage. The exterior, now sporting a leaded dormer roof, still retains the essence of its stern and uncompromising military purpose, but its survival first as a bank and then as a major component of a university campus is a testimony to its durability.

The building had been out of use for a decade when the University took it over in 2015 to make it the centre for their Business School, with most of the building adapted to this task with the usual collection of teaching, research and computer rooms, areas for socializing and a café. Wisely, the decision was made to preserve some of the more elaborate flourishes of the bank’s idea of good taste, and there are some distinctly New York style decorative features in the foyer. More to the point, the building’s foundation stone and its frame, appropriately made of carved stone rather than the less expensive brick, has been preserved and is now installed above the reception desk as a very welcome piece of the building’s material heritage. The exterior, now sporting a leaded dormer roof, still retains the essence of its stern and uncompromising military purpose, but its survival first as a bank and then as a major component of a university campus is a testimony to its durability.

It is impossible to do justice to Chantal’s talk, which was stuffed full of information. Chantal does these talks quite frequently, and I do recommend that you keep an eye open for her next ones, because she provides a vivid insight into a world that is not normally associated with Chester, and which was clearly a very important part of the city’s social and economic profile from the 1930s onwards. More than any other talk that I have attended since moving to the area, this is the one that surprised me most, and left me with a new set of insights into Chester’s less publicized wartime and post-war history. Splendid.