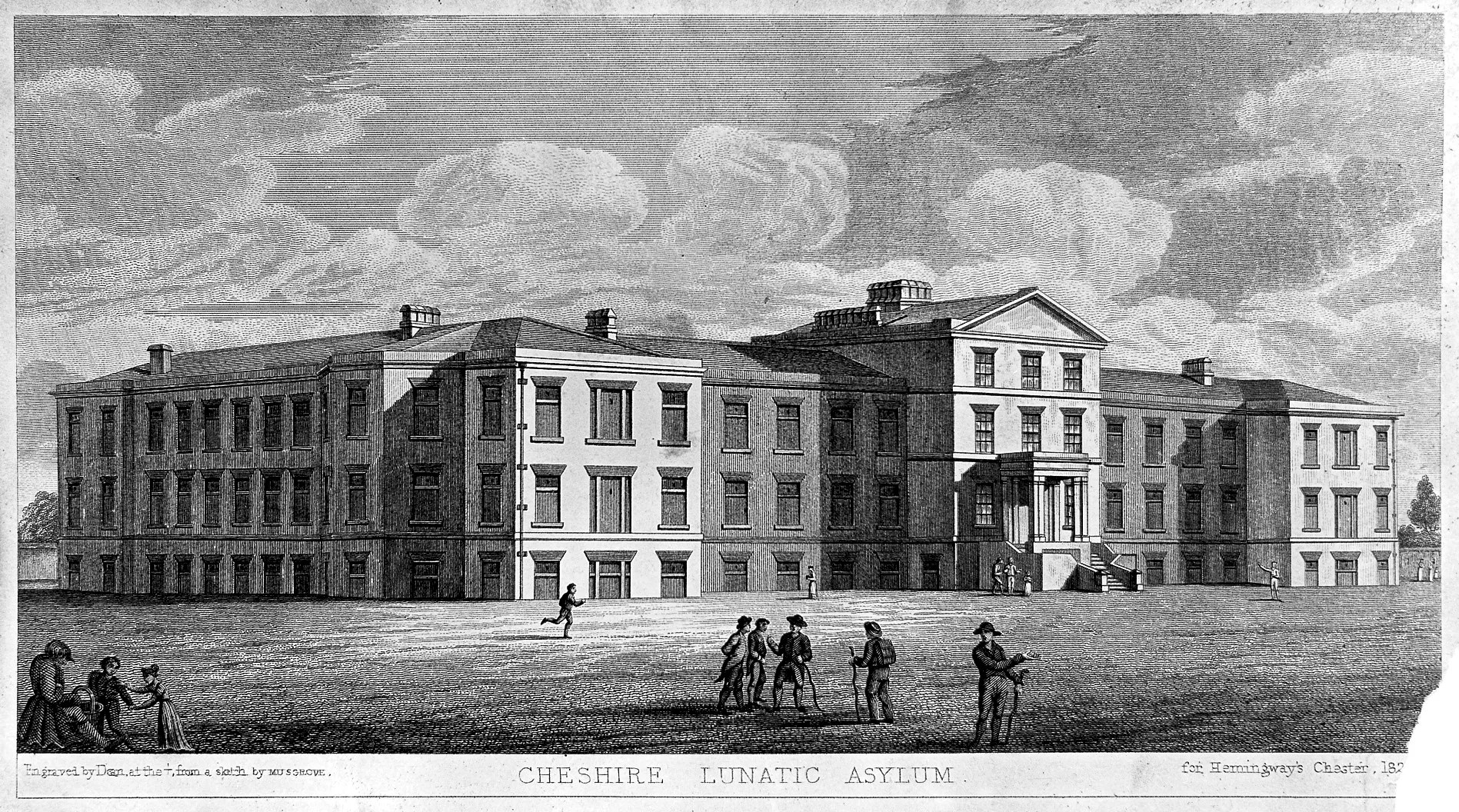

Chester Lunatic Asylum in 1831, two years after it was built. From Hemingway’s History of the City of Chester. Source: Wellcome Institute Library via Historic Hospitals, Cheshire

The 1829 Building, built as Cheshire’s first lunatic asylum, as it is today (What3Words ///tiger.manual.waving)

===

When I posted Part 1, I divided it into two (part 1.1 and part 1.2), to prevent page loading problems, and have done the same with Part 2. Both parts are too long for a blog, and when I have the time during the winter I will probably put them on a website of their own. Part 1 introduced the Chester Lunatic Asylum and discusses the general background to lunatic asylums in England and Wales from the 18th century throughout the 19th century, including medical and legal approaches to a growing problem, as well as some scandalous cases of illegitimate incarceration. Part 1.1 also addressed some of the terminology used in these two parts (such as “lunatic,” “asylum,” “idiot” etc) that are considered pejorative today, but were part of the standard vocabulary of the Victorian period.

Part 2 focuses at the Chester asylum itself, the name of which changed several times since its foundation as the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum in 1829. Again, it has been divided into two parts, mainly because of the number of images used, which would take too long to load if I left it as a single piece. This is part 2.1. Part 2.2 is here.

As I have said in Part 1.1, I first became aware of the Chester Lunatic Asylum when I was doing some research into 19th century suicides in Chester as part of a larger and ongoing project about Overleigh Cemetery, and found that most of the suicides had been deemed to be insane at the time of their deaths. This lead me to find more about how insanity was handled in the area, and I discovered that there had been a lunatic asylum at Upton in Chester, something that most long-term Chester residents probably already know. I found that the original asylum building and some of its related structures were still standing, and began to look into the asylum and its history.

As I have said in Part 1.1, I first became aware of the Chester Lunatic Asylum when I was doing some research into 19th century suicides in Chester as part of a larger and ongoing project about Overleigh Cemetery, and found that most of the suicides had been deemed to be insane at the time of their deaths. This lead me to find more about how insanity was handled in the area, and I discovered that there had been a lunatic asylum at Upton in Chester, something that most long-term Chester residents probably already know. I found that the original asylum building and some of its related structures were still standing, and began to look into the asylum and its history.

The Cheshire Lunatic Asylum was a public institution that opened in 1829 to house pauper lunatics as well as a limited number of paying private patients. The asylum opened on a 10 acre site to accommodate 45 women and 45 men, reflecting the fairly even numbers of both men and women at asylums in the 19th century. The asylum grew throughout the 19th century into the 20th century, and eventually occupied a significant area of over more than 55 acres. The term “pauper” covers a range of people. Some were genuinely very impoverished; others were employed but their were unable to afford asylum costs.

The emphasis in the following post is on letting the asylum speak for itself as much as possible. I have made extensive use of quotations from the annual Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendents. This was a legally required document, produced by every asylum to account for itself in terms of both performance and financial management for the period of the previous year. There is an immediacy to the original material that provides a vivid sense of the asylum. The reports used here cover a period of 16 years, between 1854 and 1870. A new medical superintendent had been installed at the asylum in 1853 following a very negative report by the Visiting Commissioners in Lunacy, so the 1854 report marks the beginning of a new era.

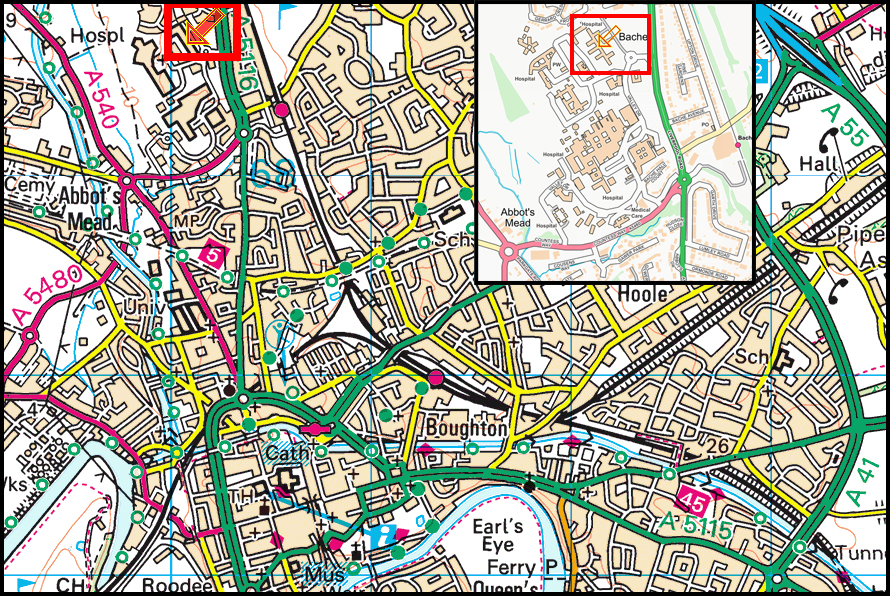

The location of The 1829 Building. Source: streetmap.co.uk

===

Prosperity and poverty in 19th century Chester

Because the Chester Lunatic Asylum was built primarily to cater for paupers, it seems useful to provide a very brief summary of the nature of poverty in Chester in the mid 1800s, the period in which the reports used for this post were produced.

Chester Railway Station. Photograph by Tanya Dedyukhina, CC BY 3.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Victoria History argues that the mid-19th century “was Chester’s most successful period between 1762 and 1914” and Handley describes the 1860s and early 1870s as “relatively buoyant,” unlike other regions in which hunger riots had broken out. Although the Industrial Revolution did not transform Chester in the same way that it did elsewhere in the northwest, it left its mark. Although the river Dee had been an important artery connecting Chester to the sea, and had once had a prosperous shipbuilding industry and marine port, silting eventually undermined its important role. This meant that throughout the 19th century the emphasis on water-borne trade shifted to Liverpool. With the declining importance of Chester as a port and the arrival of the railway in 1840, the Chester canal system became largely redundant. The railway, with today’s station opening in 1848, provided temporary work for both engineers and unskilled labourers and more permanent work for a much smaller number. A varied economy helped to spread the risk of low industrialization compared to other areas. Light industry was organized mainly in the canal basin and railway areas, expanding south of the river to the Saltney area. Industrial activity was represented by engineering companies, metal manufacturing, steam mills, a lead works, an anchor and chain works, three oil refineries and a chemical works amongst other enterprises. Craft trades continued to thrive, including tailoring, shoe-making, milliners, dressmaking, bookbinders, cabinet makers, jewellers and goldsmiths. Domestic service was an important source of employment for the less well off, in both the town centre and the suburbs, as was gardening. Retail and related services such as banking and insurance grew in importance. Tourism became an important source of income thanks to the railway, and Chester was a popular shopping destination. Chester’s expansion of commerce and light industry included roles for unskilled workers, but although many of these might earn enough to support themselves and their families, they were able not to afford such luxuries as health care, including private asylums, and it was often difficult to find job security.

Chester’s prosperous image concealed an underbelly of poverty, with dreadful insanitary conditions concentrated in slum areas known as “the courts.” Whilst St John’s parish became particularly notorious there were patches of poverty in the Boughton, Newtown, Hoole and Handbridge. The Irish Famine of 1845-52 drove starving people out of Ireland, and Chester received a large number of impoverished Irish refugees, including entire families, many of whom moved into the poorer quarters of Chester, with a concentration around Steven Street in Boughton.

Unsurprisingly the population grew on the back of all this activity. Figures have been provided by John Herson as follows, showing how during the period of the asylum the population grew and continued to grow after the Victorian period, as shown in the graph to the right. Michael Handley points out that pauperism increased at an even greater rate than population growth, with an increase in vagrancy as well, causing problems for all institutions that provided support for the poor.

From the mid-18th century Chester developed a strong line in charitable and philanthropic activities, with a new workhouse, infirmary and various other institutions supporting paupers. Pauper children could be subsumed into the general population of the impoverished. Although charity and church schools took in some of the poorer children, the most impoverished and vulnerable, sometimes the children of criminals and certainly in danger of becoming criminals themselves, were not at first provided for. Some of them entered the workhouse, and others were taken into the lunatic asylum, but the problem of pauper children was eventually recognized by Chester philanthropists and three free schools for known as “ragged schools” were built. In 1900 a children’s home was built just outside Chester on Wrexham Road, which still stands, now converted to residential use.

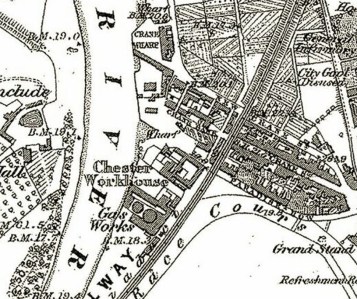

The Chester Workhouse on the Roodee. Source: Chesterwiki

One of the last-resort solutions for those who were out of work and unable to support themselves was the workhouse. The workhouse was not an intentionally punitive institution before the New Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, but afterwards became a means of driving the able-bodied poor back into employment, becoming notorious for their harsh policies and conditions.

The first Chester workhouse was established in 1575 just outside the Northgate and more parish workhouses were established after the Workhouse Test Act of 1723. From 1793 and 1869 poor relief was administered by the Chester Local Act. In 1790 nine Chester parishes joined forces to become an incorporation governed by the mayor, justices of the peace and a large committee of guardians, and took control of the workhouse from the city council under a 99 year lease at a fixed annual rate. The workhouse was on the Roodee, with the river in front of it. It was flanked by a gasworks on one side and a timber yard on the other, with the the railway eventually built behind it. The New Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 imposed new rules on workhouses, but the Incorporations like Chester’s were largely exempt and Chester refused to release control of the workhouse, maintaining its independence. After 1845 workhouses were subject to inspections in the same way as lunatic asylums, and there were frequent negative remarks in the reports. As Handley put it, the Chester workhouse “deteriorated from inadequate to calamitous as the population rose by 66% from 1831 to 1871, accompanied by increased pauperism,” and there had been no new accommodation added since 1834. The Incorporation only gave up its right to run the workhouse in 1869, and at that time the Incorporation became the Poor Law Union. In 1871 it absorbed the Great Boughton Union. Between 1874 and 1878 a new union workhouse was built in Hoole with a separate infirmary and school, and the old Roodee building became a confectionery works. The entire Hoole establishment was eventually converted to use as a hospital in 1930, and became the Chester City Hospital in 1948.

===

The medical-institutional context in Chester in the 18th and 19th centuries

The Bluecoat School, Chester, which became temporarily became a hospital in 1755. By Dennis Turner, CC BY-SA 2.0. Source: Wikipedia

By 1829, when the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum opened in the Upton area of Chester, the city was becoming well supplied with institutions that took in the poor, the sick and those suffering with mental illnesses.

The Victoria History for Chester lists a number of medical institutions from the 18th century. In the early 18th century a charity dispensing medicines to the poor was set up in 1721. In 1753 an endowment enabled the establishment of the General County Infirmary. It was temporarily based in the Bluecoat School at Northgate, receiving out-patients in 1755 and in-patients from 1756, moving to its new site facing City Walls Road in 1761, with fever wards added in 1784 and remodelling carried out in 1830. A dental surgeon joined the hospital in 1853 and an ophthalmic surgeon was added in 1885. Nearly all the positions were unpaid, with work being carried out on a charitable basis. The hospital also began to treat patients from beyond the city parishes, as well as paupers from other institutions including the county gaol, the workhouse and those being held in police cells.

In 1798 Dr Griffith Rowland funded the Benevolent Institute, a subscription charity that provided midwives for poor women. Temporary isolation wards for infections diseases were established for outbreaks of cholera in 1832, 1849 and 1866 but in 1899 a permanent isolation hospital was opened for 46 patients, supplemented by temporary accommodation during outbreaks. A homeopathic institute was established in Lower Bridge Street in 1855 followed by a free homeopathic dispensary in 1878.

Table from the 1868 “Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor” 1868 showing Chester pauper lunatics not in asylums. It is not surprising, looking at this, that in 1871 a new asylum was opened in Macclesfielld in 1871.

Workhouses inevitably admitted those who became sick or experienced injuries, as well as the insane and those with learning difficulties. At the Chester workhouse, the sick were either visited by Chester Infirmary medical staff or were admitted to the infirmary itself. In 1861 the Poor Law Board published a record of the names of 29 adult paupers who had been inmates for a continuous period of five years or more, of whom 9 had a weak mind (31%) and 2 were subject to fits (5.9%). Fits could be a sign of epilepsy, but were treated as bouts of madness. There was no strategy for dealing with the sick and the mentally ill. Handley’s verdict is that the board “simply responded to the pressure of circumstances,” not adding a an infirmary until 1842. The new Chester workhouse at Hoole provided a ward for imbeciles and lunatics in its own block in the late 1870s. After 1834 workhouses were supposed to send their mentally ill patients, and those with learning difficulties, to the local asylum, but this did not always happen as the cost of referring patients could be higher than retaining them, particularly when an infirmary or a lunatic ward had been built.

According to the Victoria History, two private asylums are recorded on Foregate Street in 1787 but otherwise the only provision for the mentally unwell was the workhouse,Lunatic asylums for paupers had been built elsewhere in England, after the County Asylums Act of 1808 which permitted the use of county funds and the raising of rates to pay for them. Few asylums were built at this time but they included Norfolk in 1814, Lincolnshire in 1820, Cornwall in 1820 and Gloucester in 1823. The County Asylums Act of 1828 gave county magistrates the right to take out loans to help pay for asylums, and tightened up administrative procedures and overall accountability. The Cheshire Lunatic Asylum followed in 1829. It was not until 1845 that the Lunacy Act of that year made county asylums compulsory. Andrew Scull, having ruled out a direct correlation between industrial cities and large asylums, suggest that expanding market economies and commercialization were more influential, and this does seem to mesh with conditions in Chester, where prosperity was on the rise of the merchant class and new light industries.

Sketch of the original plan of the Chester workhouse at Hoole. Source: Chester – A Virtual Stroll Around the Walls

In 1837 the Poor Law Commissioners estimated that there were 2780 (20%) “Pauper Lunatics and Idiots” in pauper lunatic asylums, 1491 (11%) in private asylums and 9396 (69%) in workhouses or on outdoor relief (figures assembled by Alistair Ritch). Mentally ill patients, and those with learning difficulties were frequently exchanged between asylums and workhouses, as well as between different asylums. In Chester, the workhouse sent its violent and difficult mentally ill patients to the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum, but also received those who were deemed to be long-term and incurable but harmless in return. This was nearly always due to over-crowding and although there were guidelines and criteria for what sort of patients should be held in each institution, it was not always possible to follow these, and decisions were often based on what was needed at the time, rather than being informed by laws, regulations or specific strategies. The New Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 determined that dangerous patients were to be sent to the asylum, along with those who might be cured, and incurable harmless patients could be retained in the workhouse, but beyond these broad distinctions, the criteria for which patients should go to the workhouse and which the asylum, and who was in charge of the decision-making process, were never fully delineated. The Lunacy Amendment Act of 1862 lead to many workhouses building new wards for the intake of lunatics and those with learning difficulties.

The opening of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum 1829

The Cheshire County Lunatic Asylum opened in 1829 as a public treatment centre for those with mental illnesses, catering for the entire county. It had capacity for 90 patients, half of them men and half of them women, consisting of 70 paupers and 20 private patients. When I first looked up the asylum online to see what it had looked like, I was surprised that the exterior had the appearance of an elegant and stately neoclassical building, looking very much more like a property attached to a country estate than the intimidating prison-type establishment that I had been expecting.

The asylum had been built as the result of the County Asylums Act of 1828, which gave county magistrates the right to build new asylums. The Act did not make building of county parishes obligatory, and many counties did not bother until the 1845 Lunacy Act, which did make the building of county asylums compulsory. This makes the Chester lunatic asylum of 1829 something of a pioneer, built only a year after the 1828 Act. The need for the asylum was proved as patient numbers rose and the asylum itself began to expand to meet a demand that grew throughout the period.

The annual rates could be used to pay for asylums, and rates could be raised to absorb the cost. Ongoing costs were paid for, per patient, by the parishes, townships and unions from all over Cheshire whose Relieving Officers sent patients to the asylum. Relieving Officers were responsible for the managing the relief of the poor in parishes. Sometimes asylums were additionally supported by town council grants and charitable donations, and the Chester asylum benefitted from both. Small numbers of private patients were also included, and these contributed to the asylum’s overheads. The patients who worked in the asylum as part of their treatment eventually helped move the asylum towards self-sufficiency, with both men and women making most of the clothing and bedding in-house. Men additionally helped with building alterations, whilst the asylum farm in which patients worked helped to provide the patients with food. A charitable fund was eventually set up to help those who were discharged from the asylum to re-establish themselves.

The former editor of the Chester Courant newspaper and author of History of the City of Chester, from Its Foundation to the Present Time, Joseph Hemingway, writing in 1831, two years after the asylum opened, describes the institution as follows:

A short distance from the road on the left, stands a large building, erected under the direction of the county magistrates, as a county lunatic asylum. This benevolent institution was raised at the expense of the county; to which that never failing source of revenue, the river Weaver, materially contributed. It occupies, with its gardens, airing grounds and roads, ten statute acres of land, which was purchased from the late Revr. Sir Philip Egerton, Bart. The terms for maintaining lunatic paupers belonging to the county are 7s.6d. per week; and – those beyond its limits, 10s. The unfortunate inmates of a higher class are provided, for by special agreement. . . . Ll. Jones M.D. is the physician, Mr. W. Rose, medical superintendent, and Mrs. Bird, matron of the institution.

Plan of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum 1828. Source: A History of the County of Chester: Volume 5, Part 2

The Chester lunatic asylum was a brick-built 17-bay building with stone dressings retains its elegant neoclassical exterior. It was designed by the County Architect, William Cole jr., and bears a strong resemblance to the 1751 St Luke’s Asylum in London. It was started in 1827 and completed in just two years. There were three main arrangements chosen for asylum designs: the single corridor type, in which individual wards and rooms were connected by one main corridor in the same building, centralized star-corridor arrangements where a central building was connected to outer buildings by a series of corridors, and pavilion types in which separate buildings were all built on the same site. The Chester asylum was of the first type, built with a main corridor that drew the two sides together, with men on one side and women on the other, divided by the central administrative block. Additional separate buildings were added on the site as required.

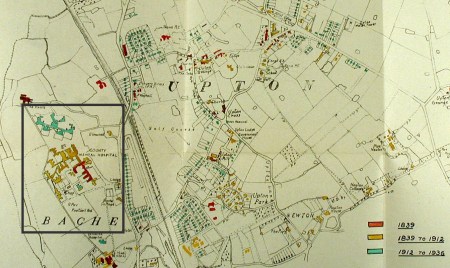

A suggestion of the extent and dating of the asylum as it grew from 1839 to 1936, with the red section including the original 1829 building. Source: History of Upton-by-Chester

The resemblance to wealthy country estates on the outside was merely aesthetic. Interiors were modelled on institutions like workhouses and hospitals, combining a dignified and attractive external appearance, representing civic pride, with the requirements of large and complex institutional operations. Requirements included food acquisition, preparation and production; cleaning, sanitation and laundry; exercise indoors and out; entertainment and sport; supply of clothing and bedding; furnishings; specialized areas for treatment and segregation; confinement; medical oversight including the provision of drugs; the sourcing and accommodation of management, supervision, nursing personnel and attendants (also known as keepers); and on-site religious guidance. It is clear that whoever employed William Cole or was very familiar with the current thinking about asylum design and building requirements for patient treatment. Cole’s layout was based on long corridors connecting both sides of the building with the central area and two wings (known a return ranges).

The central 3-storey section of the building under the brightly coloured pediment contained the administrative offices, a chapel, and housed the medical superintendent, the matron and the bedrooms of senior staff. The design in the pediment consists of a central coat of arms showing the three sheaves of Cheshire The rest of the building was 2-storey and stretched either side of the central block. The interior consisted of wards and rooms that were connected by corridors, with men on one side and women on the other. Basements ran the full length and as well as containing functional areas like the laundry, bakery and kitchens, also housed some of the more uncontrollable patients. Flanking wings (return ranges) were parallel to the main drive that extended to Liverpool Road and either side of the drive were “airing courts” where patients could walk and benefit from fresh air and carefully chosen plantings. There was provision within the building for a hierarchy of administration and nursing, food storage and kitchens, a bakery, a laundry, spaces for recreation and exercise, secure rooms and equipment for restraint (abolished at the asylum in 1854) and isolation, areas for specialized treatments as well as nurses’ accommodation, a boiler house and a splendid brick-built water tower (the latter recently restored, located on Frost Drive, in the middle of a housing estate, indicating just how much the asylum’s footprint has now been reduced). There were two lodges, one at the main road where the head gardener lived with his wife, the latter working as entrance keeper. Another lodge was located in front of the great court and its main gates, and was managed by the head porter.

The central 3-storey section of the building under the brightly coloured pediment contained the administrative offices, a chapel, and housed the medical superintendent, the matron and the bedrooms of senior staff. The design in the pediment consists of a central coat of arms showing the three sheaves of Cheshire The rest of the building was 2-storey and stretched either side of the central block. The interior consisted of wards and rooms that were connected by corridors, with men on one side and women on the other. Basements ran the full length and as well as containing functional areas like the laundry, bakery and kitchens, also housed some of the more uncontrollable patients. Flanking wings (return ranges) were parallel to the main drive that extended to Liverpool Road and either side of the drive were “airing courts” where patients could walk and benefit from fresh air and carefully chosen plantings. There was provision within the building for a hierarchy of administration and nursing, food storage and kitchens, a bakery, a laundry, spaces for recreation and exercise, secure rooms and equipment for restraint (abolished at the asylum in 1854) and isolation, areas for specialized treatments as well as nurses’ accommodation, a boiler house and a splendid brick-built water tower (the latter recently restored, located on Frost Drive, in the middle of a housing estate, indicating just how much the asylum’s footprint has now been reduced). There were two lodges, one at the main road where the head gardener lived with his wife, the latter working as entrance keeper. Another lodge was located in front of the great court and its main gates, and was managed by the head porter.

Every year the the annual Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendents recorded details of repairs to the interior and exterior of the building, and on the whole the building seems to have been well built and maintained, with both practical considerations and quality of life being taken into account.

As the asylum expanded several times to meet the growing needs of growing inmate population other architects were brought in develop it. It was first extended to the rear in 1849 and again between 1857 and 1863. The 1863 development was designed by Thomas Penson and unlike the original building was gothic revival in style, reminiscent of Penson’s earlier 1858 Crypt Chambers on Chester’s Eastgate Street. Most of the additional buildings have now been demolished and replaced by both newer hospital buildings and housing, but the asylum building that opened on 25th August 1829 and the former 1856 Grade II listed 6-bay chapel have both survived, now in use for other functions, as well as the later water tower that replaced the hand-operated pump. One of the former epileptic treatment villas dating to around 1912 is still standing, but boarded up and fenced off.

The annual Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendents for 1854 comments that following the appointment of a new medical superintendent in 1853, improvements were required for the care of patients and these were of a very basic nature. Essential improvements, for example, included clothing, bedding and cutlery. That raises questions about the standards of care and the attention to patient environment between its establishment in 1829 and 1853, but after that it seems clear that the emphasis was very much on the approach advocated by William and Samuel Tuke, Robert Gardiner Hill and others, who developed the “moral approach” that attempted to treat patients as individual members a community, reducing punitive treatments and eliminating mechanical restraints.

Reflecting its complex history, the 1829 Cheshire Lunatic Asylum underwent a number of name changes. The National Archives list them as follows:

- 1855 Cheshire Lunatic Asylum

- 1899 Cheshire County Lunatic Asylum

- 1921 Cheshire County Mental Hospital (when Cheshire County Council assumed responsibility, for the first time dropping the word “asylum” in favour of hospital, reflecting a change in attitude to care for the mentally ill)

- 1948 Upton Mental Hospital (when the new NHS assumed responsibility)

- 1950? Deva Hospital

- 1965 West Cheshire Hospital

- 1984 Countess of Chester Hospital

It should be noted that different sources list different dates and names. The annual Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendents, for example, does not record a change of name between 1855 and 1869. In 1870 however, in the report for 1869, the name was changed from the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum to the Chester County Lunatic Asylum.

Thomas Nadauld Brushfield in later life. He was appointed in 1853 and remained at the infirmary until 1866. Source: Wikipedia

Far more nebulous in the records than name changes are the different regimes that operated throughout the asylum’s history, under different superintendent, physicians, matrons and the body of staff responsible for supporting patients and handling patients directly. The ideological lead of a superintendent in any asylum was all-important, but so was the availability of resources and the willingness of those financing an institute to make them available at different times for repairs, expansion, new equipment, better quality food and medicines, and higher salaries. These annual reports demonstrate how oversight by the Committee, its Chairman and the visiting Lunacy Commissioners were important to the maintenance of standards.

A number of different superintendents were employed at the asylum between 1854 and 1870, the period that this post covers. In 1853 Thomas Nadauld Brushfield M.R.C.S. (Member of the Royal College of Surgeons) (1828 – 1910) was appointed, remaining in the office for thirteen years until 1866, becoming the first resident Medical Superintendent. Having completed his university studies in medicine, he worked for a period at the Bethnal House Asylum in London, the conditions of which horrified him. From his Chester Asylum reports, it seems that the experience encouraged him to become a follower of the moral treatment ideology, which he implemented in numerous ways at the Chester asylum, including the implementation of a regime of treatment without mechanical restraint. Beyond the asylum, he made a significant contribution to the understanding of Roman Chester, recording and publishing the hypocaust of the aisled exercise hall and hypocausts belonging to the Roman fortress baths in 1863, when the Feathers Inn was demolished. His 106 page report in the Chester Archaeological and Historial Society (founded 1849) accompanied by photographs that have been He left in 1866 to become the Medical Superintendent at the new Brookwood Lunatic Asylum in Woking, Surrey, which opened in 1867 with a capacity for 650 patients.

Dr Brushfield was replaced by H.L. Harper M.D. who had been Assistant Medical Officer for the asylum and was now promoted to Medical Superintendent at the asylum for 1866 and 1867. Harper resigned in 1867, although it is not stated why in the relevant report. Harper was replaced by John H. Davidson M.D. in 1868, the former Assistant Medical Officer for the previous 12 months, who was still in the position when the online reports end in 1870. Davidson’s promotion left a vacancy for the Assistant Medical Officer, which was filled in 1868 by Dr Arthur Strange of the Gloucester Asylum. Davidson is notable for his 1875 publication A Visit To a Turkish Lunatic Asylum, when he was apparently still Medical Superintendent at the Chester asylum.

Primary Sources

Records consulted in this post

Most of the documentation for the Chester asylum is held by Cheshire Archives and Local Studies, which has not yet digitized the asylum’s records and which is closed until 2026, so for the time being the records are unavailable. Fortunately, there are a set of the Reports of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendents available for download on the Wellcome Collection website, covering the years 1854 to 1870. Considered both individually and together, these do have some very interesting information to impart.

Also available are the Reports of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor collated and reported on by the commissioners responsible for public asylum oversight, which were sent to the Lord Chancellor. Not all of these are available for the period in which the Chester asylum was operating in the 19th century, and not all of them mention the asylum, but there are some useful references in those reports that I have located, dating from 1854 to 1870.

Use has been made of records of deaths at the asylum from Overleigh Cemetery provided by Christine Kemp’s research, which she has recorded on the Find A Grave website. Chris’s research into Overleigh Cemetery has provided information about some of those asylum patients who were buried from when the Cemetery first opened in 1850. This includes information inscribed on graves, plot details, and newspaper reports about some of the deaths concerned.

xxx

Records that have not been consulted

Title page of the of the 21st Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor 1867 (for the year 1866)

This overview of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum is obviously incomplete without access to other records. The most important are the Asylum’s own records, which are held at the Cheshire Archives and Local Studies and will not be available until 2026. In addition, I have not yet managed to gain access to the data held by the Riverside Museum in Chester where other archives that have not yet been digitized are held.

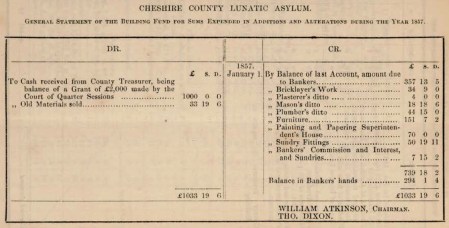

The majority of this post has been based on the Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendents, but as mentioned above I have only have only been able to access the records for the years 1854 – 1870, and this means that it is impossible to make any statements about long-term trends from 1829 to the end of the 19th century. Given how much data is in these reports, to which I have barely been able to do justice, it is probably just as well! In addition, although the reports include accounting information, I have not attempted to tackle this source of data, because accounting is not one of my skill-sets, although I have included a few screen grabs to show what sort of data is available.

Originally I had intended to use both Reports of the Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor, in which the reports submitted by individual asylums and the visiting inspectors were collated into a single annual report on the state of lunatic asylums. I had also planned to use newspaper reports from online archives. Unfortunately, this post is already very long, so that plan has been shelved for the time being.

Doubtless records from other institutions will also come to light, such as workhouse and other asylum archives that detail patient transfers to and from the asylum.

Information available from the annual Visitor and Superintendent Reports

In 1845 the new lunacy laws required that the Commissioners of Lunacy should report to the Lord Chancellor on the state of every public asylum. Reporting requirements were therefore standardized at the same time. Part of this reporting process included a report made by every asylum for the Lunacy Commission and this was collated into an overall report for the Lord Chancellor. Accordingly, each year the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum produced its Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendent of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum, presented to the General Quarter Sessions of the Peace and submitted to the Lunacy Commissioners. The chairman of the asylum’s committee, the medical superintendent and the two visiting lunacy commissioners, as well as sometimes the chaplain, all contributed to this annual report. As most of this post is based on these reports from 1854 to 1870, below is a brief description of the format of these reports. I have used the earliest as an example, which was published in 1855, but covered the year 1854, twenty five years after the asylum first opened. Although the reports could presumably be massaged to provide an acceptable face, after the Lunacy Act of 1845 the combination of record-keeping and oversight by the committee responsible for the asylum, together with visits by the Lunacy Commission, helped to make public asylums more accountable than they ever had been before.

The title page changed very little from year to year. It shows that the report is made to the General Quarter Sessions of the Peace, and that this took place at Chester Castle on the 2nd July 1855. The General Quarter Sessions of the Peace, usually abbreviated in reports to to “the Quarter Sessions,” were local courts in England and Wales presided over by Justices of the Peace and held four times a year. The PRESENTED BY stamp was signed by the incumbent medical superintendent for the asylum, and was counter-stamped by the Royal College of Surgeons. Later, the county arms were added to the bottom of the report.

The report goes on to present narrative accounts of the state of the asylum for 1854. After the reports for 1854 and 1855 these were standardized to include a statement by the Chairman of the committee that oversaw the asylum, another by two commissioners of the Lunacy Commission and an account of the main points of the year by the Medical Superintendent. These are followed by a series of statistical tables, including information about patient numbers and activities, and accounting information. None of the patients are mentioned by name in either the accounts or the tables and there are very few references to individual patients unless one had escaped, committed suicide or was otherwise a particularly notable case.

The running order of the individual contributions to the report changed from year to year, although the format of the statistical tables was very rarely altered. In the 1855 report for 1854 the first of the reports was by the Committee of Visitors, which gave an overview of what they believed to be the most important aspects of the year’s main findings including building works and the associated costs. A number of personnel retirements were also associated with costs for pensions. Concerns were expressed about the number of admissions during 1854 and the fact that the building would have to be further expanded if numbers were to continue rising. In future reports the Chairman made a separate statement, but in this report the Committee of Visitors report was countersigned by the chairman.

This was followed by the Medical Superintendent’s statement. For 1854 this went into some detail under 16 side-headings: Admissions; recoveries, deaths; general health; suicidal cases; general paralysis; restraint; escapes; employment; amusements; exercise beyond boundaries; diet; dinner and services; clothing and bedding; night attendants; and removal of heavy guards (the latter referring to window guards). The headings could change slightly from one year to the next depending on what was deemed to be the most important information for a given year. In some years accounts were very much shorter than in others

To give a flavour of the superintendent’s statement, Dr T.N Brushfield notes that at the beginning of 1854 there were 102 patients, 52 men, 50 women; by the end of 1854, counted on January 1st 1855, there were 254 patients (108 men and 146 women) as well as 102 new admissions of which there were a greater number of men than women. Interestingly Brushfield comments the importance of a speedy referral to the asylum of mentally ill patients so that they could be treated effectively. This reflects a widespread view in the alienist community that speedy referral was key to any hope of a cure. Brushfield adds that many of the new admissions were in such a poor physical state that both dietary improvements and stimulants had to be employed but that even when there was bodily improvement, in the cases of patients admitted in such poor physical condition “the mind remained in an impaired condition.” Only 64 patients were discharged, and 30 died. Of the deaths, representing 8.92% of the patients under treatment, 30% of them were victims of “general paralysis,” far more common in men than women, and on which more later. 42 suicidal patients had been admitted, 26 of which had actually attempted suicide, more of them men than women, and in several cases unsuccessfully attempted again after admission. “Several” patients had escaped, but all had been recaptured in less than a day.

Dr Brushfield goes on to comment on the general conditions of the asylum. He reports, for example, that “the clothing has been much altered in character and made warmer and more cheerful looking. The bedding has been considerably improved; the number of straw beds diminished; the straw pillows altogether disused, those stuffed with flock or coir have been substituted.” Other fundamental improvements included improved diet “of a less liquid nature” (but including the introduction of beer for women as well as men!), and improved dining equipment: “Dinner and Services: Earthenware plates, crockery, cups and metal spoons, knives and forks have been supplied to the whole of the inmates in place of the tin plates, horn cups and wood spoons which were in use until the early part of the year.”

These were very basic improvements in the quality of everyday life for patients, but would certainly have been appreciated. There was a matter of pride in the fact that restraints of all forms had been “entirely abolished.” Although this had been actioned in 1853, this was in accordance with new rules rather than an independent initiative. However, the approach that was taken was very much the initiative of the asylum. Instead of being restrained, patients were given a new sense of direction. Men were employed in activities relating to the maintenance of the building and the grounds, whilst women took over from tradesmen the making and repairing of clothing and similar needlework. One of the subsequent tables lists the works undertaken by both men and women.

Next, there are 18 numbered tables that record key details about the asylum, its patients and accounts. These are particularly useful as they can be compared from one year to the next. Even when the template changed slightly, most of the tabulated data was retained in much the same format, with data separated for men and women: I) Admissions, discharges and deaths during the year; II) Admissions, discharges and deaths relative to the month of the year; III) Civil State – Admissions; IV) Ages at time of admission; V) Duration of insanity prior to admission; VI) Occupations of those admitted; VII) Religious persuasion – Admissions; VIII) Bodily condition – Admissions; IX) Form of mental disorder – Admissions; X) Supposed cause – Admissions; XI) Analysis of suicidal cases – Admissions; XII) Suicide attempts; XIII) Duration of residence of those discharged and relieved; XIV) Causes of death; XV) Ages of patients who have died; XVI) Duration of treatment of patients who have died; XVII) List of articles of clothing made and repaired during the year; XVIII) Extract from daily account of patients.

Finally there are a set of unnumbered tables that related to the asylum’s accounts. These tended to vary from year to year, but their intention was to capture income and expenditure for the period. Tables that floated from one year to the next were The Average Cost Per Head Per Week of Patients and the Balance Sheet.

===

Insights from the Visitor and Superintendent Reports for 1854-1870

I have divided this section into some of the themes discussed in the reports, although by no means all, to give a sense of what sort of things were important both to the visiting inspectors and to the superintendent who was in charge of trying to secure more resources for the asylum.

===

Ideology

Robert Gardiner Hill. Source: Wikipedia

Statements in many reports address the ideology of the asylum and indicate that aspects of the moral treatment approach were incorporated from at least since 1854, as per the report for that year: “it may be stated as an axiom, that everything within the bounds of an Asylum which tends to create a cheerful impression on the minds of the inmates, is certain to have a highly salutary effect.” Most impressively, according to the report of 1855 all forms of restraint were abolished by the new Medical Superintendent, Dr Brushfield, from 1854 in accordance with new rules, and “nor has there been the slightest reason to regret such a step having been taken; it is certain that its disused has been a beneficial effect on the minds of those patients who, at an time, had been the subjects of it.” This followed in the footsteps of pioneers in the care of patients with mental illnesses like William and Samuel Tuke and (1732-1822 and 1784-1857 respectively) and Robert Gardiner Hill (1811-1878).

In line with this ideology, in 1854 a team of artisans was employed to work with patients, and various entertainments were arranged including weekly dances, a daily newspaper, periodicals, and a library that was occasionally updated with new titles. As Laura Blair explains on the Asylum Libraries website:

Within nineteenth-century asylums, attitudes towards reading were expressed as medical directives, framing reading as both a potential cause of, and cure for, mental illness. As the print culture of the era rapidly developed, with a massive increase in periodicals and newspapers following the mid-century period, asylum professionals sought to facilitate an ‘ideal’ engagement with texts. Preliminary research indicates that reading was considered an important part of patients’ leisure and was often regarded as medically therapeutic.

Suitably calm patients were accompanied on walks outside the asylum, on local roads and lanes, giving them both exercise and a wider view of the world and sometimes were even taken to local events. The range of in-house activities was extended in 1855:

Late 1890s painting “The Retreat” by George Isaac Sidebottom, showing patients at leisure in the asylum founded by William Tuke in 1796. Source: Wellcome Collection

ln the summer months bowls, skittles, quoits, bat and ball, &c., are enjoyed by the males; and on fine clays parties of both sexes, accompanied by attendants, have frequently taken long walks beyond the Asylum boundaries. Reading, and various in-door games have been encouraged as much as possible. The weekly ball has been kept up regularly throughout the year; and while serving to relieve much of the monotony of residence within the walls of an Asylum, it has also tended in many instances to produce a great amount of self-control. By a large number the weekly gathering is invariably looked forward to with much pleasure

Patients were engaged in a very wide range of tasks that supported the asylum, indoors and out, both helping the asylum’s financial burden and giving patients a real sense of purpose, such as working in the gardens and farm, or sewing clothes and bedding. The 1857 report for 1856 expressed real concern that as the building works came to an end, to which male patients had been contributing, there would be a hiatus in very beneficial activity:

As the alterations and additions to the building are on the point or completion, a great source or employment will soon be lost to the patients, and although the laying out of the airing courts, remaking roads, &c., may afford work for the next few months, yet when these are finished the present quantity of land is by no means sufficient to keep in active employ the increasing number of inmates, and us no form of labour conduces so much to the recovery of a patient as that derived from ordinary farm and garden operations, it is highly to be desired that more land should be obtained as early as possible.

Examples of the types of employment engaged in by male and female patients at the asylum, from the July 1855 report, over two pages. Source: Wellcome Collection

Accordingly, in 1859 the provision for outdoor employment was significantly expanded, providing work for many of the patients and additional produce for the Asylum kitchens:

The additional land, now under cultivation, has not only increased the means of employing the patients in healthy outdoor work, but has caused a greater variety of employment – a matter of as much importance as employment itself. A sufficient quantity of potatoes has been grown to furnish the requirements of the Asylum until the next crop comes in; hitherto, a large quantity has always had to be purchased. In addition to several acres of beans, peas, mangolds [Swiss chard], etc: 5 acres of grain crop, and l l acres of grass have been harvested by the Patients without any extraneous help. The hay-field contributed materially to afford for a time recreative employment for all the patients and attendants, ordinarily engaged in artizan employments of a sedentary nature; and some of our best haymakers were to be found amongst the Tailors and Shoemakers.

The area employed for the gardens and farmland continued to expand throughout the reports, until this report at the end of 1870, which gives a good idea of the scope of the operation:

In 1862 plans were revealed to establish a voluntary school and bible classes for those patients “who are in a condition to profit by such instruction,” and in 1863 a schoolmaster was appointed to attend twice a week,” with the most beneficial results.” The school was operated by the chaplain and was divided into two, one for men and one for women, and was operated as a leisure facility, rather than an enforced activity. It was quite popular, and for those discharged paupers who had had minimal education, if any, would provide them with addition skills such as reading, writing and basic arithmetic.

The report for 1863 contains the usual update from the visiting Commissioners In Lunacy and is a useful example of how they were always searching for improvement in patient conditions:

The state of the inmates of the old wards in both divisions was less satisfactory. Their clothing was not good; and there was an absence of tidiness and comfort. The proportion of feeble, helpless, and paralysed cases, is unusually great; and they require a larger amount of individual care on the part of attendants. Their sluggish faculties should be stimulated by continuous efforts to rouse and occupy them. There should be reading aloud among them. A few of the more intelligent patients who might not object to help in amusing this unfortunate class should be brought into their wards, and others of the more capable who are here should be removed to No.6. We learn from Dr. Brushfield that a considerable additional supply of pictures for the walls, and of games and objects of amusement, are in preparation for the wards of the old building. The patients to whom we have been adverting require a better provision of this kind. In both infirmaries, which are not cheerful rooms, the furniture is poor, and a small well-directed expenditure would go far to brighten them up.

At the same time, however, 1863 was also the year in which a croquet lawn was established, a billiard and several bagatelle tables were added to the indoor entertainments and the Prince of Wales’s wedding day on March 10th was celebrated with a fete and a display of fireworks “so arranged as to he witnessed by nearly every patient in the Asylum.”

Similarly, the 1865 report for 1864 described the continued support of Dr Brushfield’s work to provide better conditions for patients. This included the enlargement of the Recreation Hall, as well as the domestic offices underneath. The Recreation Hall was now very spacious and well ventilated, could hold up to 400 people and during the day could be divided into two, so that one part could be used for daily prayer led by the chaplain as well as other sundry activities; the other was used for sewing activities of the women patients. During the evenings, the entire space could offer large scale indoor activities for the patients.

In 1870, in spite of the rising numbers, the asylum appears to have continued with attempts to keep its patients busy and, for those for whom it was possible, entertained:

Numbers of the patients of both sexes have been steadily employed in such work as they have been capable of performing, or which has been considered likely to conduce to the improvement of their bodily or mental health. Excluding those under medical treatment in the Infirmary wards, nearly two-thirds of the patients have been regularly and industriously employed. In addition to their ordinary amusements and recreations, which, with some slight variations, were much the same as those alluded to in my Report for the preceding year,-many of the patients of both sexes were, at my request, kindly permitted by Signor Quaglieni to visit, free of charge, his Grand Italian Hippodrome when in Chester last Spring. About sixty men and an equal number of women, both under the care of Attendants, were also at the Regatta on the River Dee, where they conducted themselves with remarkable decorum.

The approach to the management of the asylum, which sought to treat patients as members of a community by providing them with useful occupations and amusements, almost certainly helped some of the asylum members to regain their stability, but this largely depends the nature of the mental illness. Although certain health issues might be addressed, mental health was still very poorly understood, and although kindness and activities were certainly an improvement on punitive institutions, there was a very long way to go before many mental illnesses could be alleviated or remedied.

xxx

Upgrades to the asylum during the period 1854-1870

One of the most important aspects of daily are of patients was the maintenance of the buildings and facilities, and the expansion of both to meet increased demand throughout the period. The increase in new admissions annually meant that in nearly every year alterations had to be made and new extension had to be added.

The 1855 Report of the Committee of Visitors and Superintendent of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum for 1854 submitted by Superintendent T.N. Brushfield is of particular interest as it is a year in which policy changes occurred, and gives an impression of a much less comfortable regime before this year. The report notes the successful completion of “alterations and additions paid for by a grant of £6500” (to put this into perspective, according to the National Archives Currency Converter, this is equivalent to about £521,209) in today’s money. This included enlargement of kitchen and workhouses, newly erected laundry, washhouse, workshops and stables. There is also mention of “an ample supply of water” but no explanation as to what the problem with the existing water supply might have been. There was also an increase of attendants and nurses from 15 to 23, as well as the addition of a night watch in the women’s wards.

In spite of the improvements, in 1854 more patients required treatment than the asylum had capacity to take, which is probably not surprising given that the asylum was taking in patients from all over Cheshire. The decision was made to further enlarge the building to take 300 patients, to add a new chapel (the existing one was both too small and deemed to be unsafe) and, now that the law required that a medical superintendent be resident, to add a new superintendent’s house near to the main building. New furnishings would also be required for all these improvements. For all this work £12,000 was required, nearly double the work that had just been completed, for which a grant was obtained from the Quarter Sessions, with the intention of ensuring that the asylum should be “equal to most of the modern institutions in the kingdom.”

In the 1856 report for 1855 there was bad news about the state of the building, but at the same time progress was also made:

The Committee regret to have to state that on proceeding with the alterations, the dry rot was discovered to have entered the flooring of several of the wards, and the additional expense incurred thereby will be considerable. Steps were immediately taken to stop its progress, and they hope the funds placed at their disposal by the Quarter Sessions will be sufficient to cover the entire expenditure. The want of additional land principally for the purpose of more fully employing the patients having long been felt, the Committee made application to Sir Philip de Malpas Grey Egerton for a portion of his land adjoining that of the Asylum, and succeeded in obtaining about six acres on the north side, and which they have taken at an annual rental of £8 per acre. The several workshops erected during last year have also afforded increased facilities for employing the patients so that the whole of the male and female clothing is now made up by them, articles of furniture manufactured for the use of the establishment, and some of the ordinary repairs clone to the building. This employment of the patients bas been attended with the most beneficial results to the parties so occupied, as well as of considerable advantage in a pecuniary point of view.

Even with these improvements, the report for 1855 expressed the concern that the asylum would soon be unable to accommodate the numbers of patients that might, on the basis of the experience of asylums across England, be expected in the coming years.

In the 1857 report for 1856, the Chairman of the Committee of Visitors was particularly pleased with the end to four years work:

In submitting a report of the proceedings of the past year in connection with this Establishment, your Committee have much pleasure in stating that the various alterations and additions which have occupied a period of nearly four years, have at length been brought to a close, and it is gratifying to them to observe now that the arrangements are quite complete, that they consider the Building has been made equal to most of the more modern Institutions, and appears well adapted for the care of the Insane, according to the recent and improved methods of treatment.

The most recent upgrades included:

-

-

- A Chapel, capable of accommodating 300 persons

- A commodious house for the Superintendent

- Carpenters and shoemakers shops and coal Stores

- Enlargement of the wash-houses and launderette with the addition of a dining room

- A Steward’s Office, and spacious Store Rooms

- Reboarding of 4 yards in the new wings, occasioned by dry rot

- Reboarding of old Chapel, and conversion of the same into a Recreation Hall

- New bathrooms and lavatories in four wards

-

The original estimate of £6000 was found to be insufficient, and a further £2000 was applied for.

In 1856 the report for 1855 had commented on the rising numbers of re-admissions from 1849 onwards, recording how increases in patient numbers represented a considerable challenge to the capacity of the asylum, and recommending more alterations to prevent overcrowding, and listed the previous years’ admissions to make the point. These concerns about increased patient admissions and re-admissions were vindicated in the 1857 report for 1856 when it was noted that although the asylum was now capable of holding 300 patients, it would actually be “full to overflowing,” had the committee not issued a notice to the unions and parishes that referred patients to the asylum to notify them that “no cases could be admitted except those which were curable or of recent origin.” The question was posed, in the same report, whether a new asylum should be built at the other side of the county (i.e. east Cheshire) to address the problem of incurable patients, or whether, instead, yet another expansion be made in the existing asylum. It stated that a decision was now a matter of urgency. At this stage, the proposal for a new asylum was clearly rejected because Parkside Asylum near Macclesfield did not open until 1871. Instead, in October, a grant of £6,000 was obtained for the purchase of 21 acres of land from Samuel Hill, Esq. “at which time it wi1s stated that probably a further application for a similar sum, and for the same purpose, would shortly be made.” Sure enough, the Committee offered the asylum “around 45 acres of land, together with the house and buildings on the same, at £250 per acre, being £50 per acre less that that recently purchased, part of which belongs to Sir Philip Egerton and part to S. Hill, Esq., and to enable them to buy which an application will be made for a grant of £11,500.” This enormous expenditure was deemed to be “highly desirable” when presented to the Court of Quarter Sessions.

The 1858 report for 1857 described some streamlining activities. For example, the erection of a new chimney shaft, the provision of a water supply in case of fire, and the conversion of “several small inconvenient airing courts into larger ones” were undertaken. At the same time, the problem of under-capacity was again considered. Although new admissions had decreased, this was only because capacity was at its absolute maximum and there was nowhere to put new patients. It was concluded that the extension of the Chester asylum would be much more cost-effective than the building of an entirely new asylum: “new Asylums generally cost from £150 to £200 per Patient, whereas the new buildings proposed to be erected will only cost £40.” Accordingly, £10,000 was requested for the erection of a building to accommodate 100 male patients, another to accommodate 100 women, the ventilation of the wash-house, and alteration of drying closets as well as a house for the chaplain and a wall to enclose the land purchased from Sir Philip Egerton.

The 1858 report for 1857 described some streamlining activities. For example, the erection of a new chimney shaft, the provision of a water supply in case of fire, and the conversion of “several small inconvenient airing courts into larger ones” were undertaken. At the same time, the problem of under-capacity was again considered. Although new admissions had decreased, this was only because capacity was at its absolute maximum and there was nowhere to put new patients. It was concluded that the extension of the Chester asylum would be much more cost-effective than the building of an entirely new asylum: “new Asylums generally cost from £150 to £200 per Patient, whereas the new buildings proposed to be erected will only cost £40.” Accordingly, £10,000 was requested for the erection of a building to accommodate 100 male patients, another to accommodate 100 women, the ventilation of the wash-house, and alteration of drying closets as well as a house for the chaplain and a wall to enclose the land purchased from Sir Philip Egerton.

In 1860 it was identified that there was an urgent need for more hot water for bathing and washing laundry. A new steam engine and boiler was installed at a cost of £1353.00 in the same year, and was reported to be a success. The 1862 report for 1861 noted that the asylum was now capable of housing 500 patients, the works including the enlargement of both the Steward’s House and Entrance Lodge, and the erection of additional farm buildings. The extra capacity at the asylum actually resulted in unused space, and the decision was made to make the most of the unused capacity by seizing the opportunity to charge private patients who were unable to afford more expensive solutions, with the addition of a new set of rules that would be applicable to these new more privileged patients:

After due deliberation, it was deemed desirable to offer the advantages of the Asylum to patients which are to be found, in considerable numbers, among the middle classes,

but whose means will not permit them to pay the high terms of respectable private establishments where, alone, the same advantages of skill and care can be obtained as are afforded in County Asylums.

In 1862 alterations were minimal but “a new and commodious staircase in the male division” replaced one “which was exceedingly dark, and to a certain extent dangerous,” and a new dwelling was built for the head attendant at the end of the new female wing. In both cases, male patients helped to carry out the work as part of the asylum’s policy to keep patients busy and entertained, and to enable to to practice existing skills and learn new ones. The asylum was not full to capacity, and this gave Dr Brushfield the opportunity to take in patients from other asylums, for which he could charge a healthy markup. 40 patients were taken in from Stafford, for a period not less than one year, and others were transferred from asylums in north Wales due to the Denbigh asylum being full to capacity. The charge made for each patient was 14s per week, “while the weekly cost per patient only amounts to 8s.2d.,” and this actually paid for much of the furnishings in the new building.

1864 saw the erection of a new dedicated gas works, built by Messrs. Porter and Co., of Lincoln, at a cost of £754, actually coming in just under budget, and in 1864 the Recreation Hall and the domestic offices beneath it were expanded, increasing the capacity of the Hall to 400 persons, which was considered very important for supporting patients during the winter, as well as providing a work space for the female patients.

Temporary buildings were erected to meet the need in 1867 to provide additional accommodation for 50 paupers. At the same time the high numbers of residents 481 at the beginning of the year, with 156 admissions over the course of the year, with only 59 discharges) required considerable improvements to the engine and pumps that supplied water to all the buildings of the asylum. In 1868 the report claimed that “in no former year has so much been done to repair, make better, embellish and render convenient the interior of the building” including refitted water closets and the addition of gas purifiers. Outdoors a walkway around the boundary was extended, aiming to make a mile-long walk for patients, and a new orchard was planted. More alterations were made in 1869 with “additional store-rooms, slop-rooms, bath-rooms, urinals and water-closets”. Adding to the quality of life were objects that might provide interest (“statuettes, pictures, birds, plants etc” as well as chintz valances fixed to window openings).

In 1870 the report demonstrated how ongoing work continued to be required, including new measures to improve the asylum. Points 1-6 are shown in the report below.

1870 asylum report bullet point improvements first page. Two other points, 7) and 8) add that the door locks between male and female wards had been changed, formerly having been the same on each side, and that machinery in the laundry room had been overhauled, resulting in considerable improvements to overall efficiency.

===

These various excerpts demonstrate how the asylum was improved from year to year between 1854 and 1870, not merely in terms of repairs to the building, but also in terms of attention to the quality of life of patients.

xxx

Admission numbers into the asylum

During the year of the 1854, the year following Dr Brushfield’s appointment, it was reported there had been an average of 255.75 inmates, with 102 admitted in that year, 52 men and 50 women, of whom 42 were reported to be suicidal, with 26 having made suicide attempts prior to admission. The age range of new admissions included two children between the ages of 5 and 10 (the youngest), and up to five adults between the ages of 60 to 70 years old (the oldest). Eight of the new cases were complicated with epilepsy and nine with “General Paralysis.” The total number of patients had risen at one point to 266, which had exceeded the capacity of the asylum, and never fell below 240, so the report recorded the decision to extend the building, to build a new chapel (which was built the following year) and, in order to conform to the latest Lunacy Act which required that the Medical Superintendent should be resident, a new house was to be built on the site to house him. These measures would remove the chaplain and superintendent from the asylum itself to provide more room, and the new building works would further increase capacity. The figure for those remaining in the asylum on January 1st 1855 was 254, made up of 108 males and 146 females.

The report for 1855 similarly notes down numbers, including a patient’s escape:

On January 1st, 1855, there were in the Asylum 254 patients (108 males and 146 females); 125 were admitted in the course of the year – 52 were discharged as recovered, 29 as relieved, 5 as unimproved, 1 escaped, and 31 died, leaving in the Asylum on 1st January, 1856, 26l inmates, of whom 119 were males, and 142 females.

The report adds that because of the building works, which required some wards to be vacated, the asylum was often “inconveniently crowded,” but the decision was made not to refuse admissions of any new cases. The 1855 intake was broken down as follows, by age:

xxx

Admission numbers varied from one year to the next, but the overall trend was one of rising admissions. Where these apparently fall in some years, this was usually not due to any lack of demand but because the asylum was full to capacity. By the mid 1860s there was now a great deal of focus on the growing patient numbers and how best to accommodate them, and the greater part of the 1864 report is dedicated to this serious issue.

The number of admissions in 1864 was greater than during any previous year since the Asylum was opened. . . The Committee, at their Monthly Meeting in September, finding that the female division was more than full, having then 256 inmates, and being capable of accommodating only 250, gave notice to the Authorities of the Stafford County Asylum to remove, as soon as they possibly could, their female patients. Since then, ten of them have been taken away; and it is expected, that in a very short time all the Staffordshire patients, both male and female, will be removed to the new Staffordshire Asylum, now ready for their reception. Supposing, then, the whole of the Staffordshire patients to be removed, and those belonging to the City of Chester continue to be accommodated, there will then remain 209 males and 222 females in the Asylum. But if the increase of the Cheshire patients go on in the same ratio as in the past year, and the City of Chester patients remain as now, in one year the female wards will be filled, and in another the male wards also. It therefore becomes a question for the Court of Quarter Sessions to take into their consideration, and that without much delay, what further accommodation shall be provided for the Pauper Lunatics of the County; and to the consideration of this question the Committee are desirous of calling the especial attention of the Court.

Dr Brushfied put this down not to a growth in population but to the Poor Law Removal Act of 1862, which changed how patient maintenance was paid for. Instead of separate Townships footing the cost, it was imposed on Parish Union funds, meaning that more patients were sent to the asylum rather than to private asylums or the workhouse. These concerns were shown to be valid. In the 1867 report on 1866, for example, the male wards were too full to take any new cases. It had been attempted to find spaces for them in the asylums at Denbigh, Stafford, Heydock Lodge (the latter a private asylum established in 1844 and licensed to hold 450 patients), and other asylums in the region, but no spaces were found. It was only with the discharge or death of patients that new places became available, and these were filled instantly. The Chairman that year was pessimistic:

Taking 40 as the average increase of lunatics per annum remaining in the Asylum, and calculating that it will take three years to erect and finishing the new building, there will be at that time 120 patients ready to occupy it.

It was concluded that if no provision could be found at Chester, excess patients would have to be moved to other asylums (if available), at extra expense, or to transfer them to workhouses. In 1865 Dr Brushfield was so worried about admission numbers that in July he felt the need to issue a special report to consider whether additional accommodation should be supplied. In 1868 admission numbers were down, but only because the Committee had refused to admit certain patients due to overcrowding.

By 1870 the new Medical Superintendent, John H. Davidson, recorded that the number of patients in the asylum at the start of the year had reached 526 patients, of which 255 were men and 271 were women. During 1870 a further 165 patients were admitted, of whom 91 were men and 74 women. The total number of patients admitted in 1870 was 691, of whom 346 were male and 345 were female. On the 1st of January, 1871, 536 remained, of whom only 17 men and 30 women were judged to be curable.

Other sources indicate that from 1870 the numbers continued to rise, even after Parkside Asylum in Macclesfield, east Cheshire was opened in 1871, in part to provide relief to the Chester asylum.

==