The Lady Lever Art Gallery is in a fabulous location within the village of Port Sunlight. Port Sunlight was the brainchild of William Hesketh Lever, who in 1911 became Baronet Lord Lever, and in 1917 Baron Lord Leverhulme, honoured for his contributions to industry, commerce and the economy. He was also remembered, amongst other achievements, for his three years as a Liberal M.P., his philanthropy and his art collections. Just off the A41, an unattractive stretch of the road characterized by untidy industrial and retail parks, the village remains a genuinely surprising and perfectly charming near-utopia of green spaces, wide boulevard-style roads and a splendid mixture of compact homes with gardens and small civic buildings, all built in a variety of architectural styles, all vernacular. Port Sunlight, named for one of the soap brands that Lever produced (Sunlight Soap), was built for the workers in the nearby factory. The Neoclassical architecture of the art gallery stands out as a monument in its own right. It was, indeed, a memorial to Lever’s late wife Elizabeth Ellen Hulme, who died in 1913, and whom he always stated was his inspiration. Although the gallery served the practical purpose of housing the best of Lord Lever’s private collections, which had outgrown his own numerous homes, it was more importantly built on his philanthropic urge to improve conditions and provide educational facilities for the working class families of his factory employees.

The Lady Lever Art Gallery is in a fabulous location within the village of Port Sunlight. Port Sunlight was the brainchild of William Hesketh Lever, who in 1911 became Baronet Lord Lever, and in 1917 Baron Lord Leverhulme, honoured for his contributions to industry, commerce and the economy. He was also remembered, amongst other achievements, for his three years as a Liberal M.P., his philanthropy and his art collections. Just off the A41, an unattractive stretch of the road characterized by untidy industrial and retail parks, the village remains a genuinely surprising and perfectly charming near-utopia of green spaces, wide boulevard-style roads and a splendid mixture of compact homes with gardens and small civic buildings, all built in a variety of architectural styles, all vernacular. Port Sunlight, named for one of the soap brands that Lever produced (Sunlight Soap), was built for the workers in the nearby factory. The Neoclassical architecture of the art gallery stands out as a monument in its own right. It was, indeed, a memorial to Lever’s late wife Elizabeth Ellen Hulme, who died in 1913, and whom he always stated was his inspiration. Although the gallery served the practical purpose of housing the best of Lord Lever’s private collections, which had outgrown his own numerous homes, it was more importantly built on his philanthropic urge to improve conditions and provide educational facilities for the working class families of his factory employees.

The Lady Lever Art Gallery. Photograph by Rich Daley, Wikimedia

Originally the museum was designed to be entered from the front, its big entrance overlooking the boating pond and the long green avenue beyond towards the massive war memorial. Today the boating pond has been drained of water, with warning signs to prevent people climbing in (Julian, with whom I visited, predicts that it will become a flower bed!). There is plenty of free parking in front of the museum, as well as on the surrounding roads. Today the entrance to the gallery is at the side, left as you face the front, next to a ramp that leads to the basement with its excellent café and its little shop. There is no charge for visiting the permanent collection. You are offered a map at the desk, and we did find that this was helpful, although once you have worked out that it is organized by rooms around a main hall, with a circular room at each end, each linking together another set of rooms, it’s very straight-forward to navigate. Having said that, looking at the map at home after the visit I realized that there were two upstairs galleries, each a corridor that flanks the main hall, which we missed. According to the map these apparently display 19th and 20th century art. Next time!

===

The easiest way to convey the overall impression of the Lady Lever Art Gallery is to characterize it as a miniature V&A. Although there is a large collection of oil paintings and some water colours, there is also an emphasis on decorative arts including furniture, china, sculpture, tapestries, and embroidery. The multinational character of the collection is impressive and begins, chronologically, with some Classical objects, as well as a couple of items from ancient Egypt. Lord Lever had a great love of Chinese porcelain and his taste extended from the simplest of the blue and white patterns to the most elaborate and exotic polychrome extravaganzas. There are a number of very fine Indian items, but perhaps not as many as there might have been given how long the East India Company had had its claws hooked into India’s social, economic and cultural landscape. There is a small collection on display of ethnographic objects, although Lord Lever collected over 1000 pieces, and there are also a tiny number of ancient Egyptian objects, the bulk having been loaned to the Bolton Museum and Art Gallery. He also collected a massive amount of Wedgwood, including fireplaces and pieces on which Josiah Wedgwood collaborated with George Stubbs. Impressively, Lord Lever’s collection included Elizabethan and Jacobean furnishings, which are not always well represented in British museum and art gallery collections, and are really good examples of their types.

Anglo-Indian commode, 1770-80. Engraved ivory veneered on a sandalwood carcase, originally fitted with specimen draws (now missing). An English design made at Vizagapatam.

Detail of an English or Dutch chair (one of a pair), 1690-1710, emulating the Jacobean style, with mermaids and the bust of a crowned queen

There are five rooms that skilfully recreate a particular period in all its details, from wall treatments and light fittings to furnishings and art works which. These recreated rooms are splendid today but in the days before the National Trust and day-trips to aristocratic houses must have been a real revelation to visitors. Examples are the Adam Room and the William and Mary Room. Both Julian and I were horrified by the Napoleon Room; no matter how hard I tried, I was unable to find anything in it of aesthetic merit in it, although the sheer excess of it all did make me grin. There is always something to love in mad committent to a particular passion.

Sculpturally, Lord Lever’s taste extended from the Classical to the modern including, very surprisingly, a Joseph Epstein sculpture, and the variety of forms and styles is remarkable, although I have the impression that the quality is far more variable than in other art forms in the gallery. There are, however, some very fine Roman cineraria (small stone caskets that hold ashes of the dead).

In oil painting, Lord Lever’s taste focused mainly, but not exclusively, on contemporary and slightly earlier artists including George Stubbs, Joseph Mallord William Turner, William Etty, Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds, Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun and George Romney, as well as a notable selection of those from the Pre-Raphaelite school including William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “The Blessed Damozel.” There is an article about the painting on the Lady Lever Art Gallery website.

The glorious “The Falls of the Clyde” by Joseph Mallord William Turner; Lady Lever Art Gallery. Source: ArtUK

St James’s Palace. English School. Source: ArtUK

Emma Hamilton as a Bacchante. Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Lord Lever’s tastes in art were usually consistent with popular opinion, but by modern standards some have not always stood the test of time. Although Vigée Le Brun produced some very accomplished pieces, others were not quite as refined. Source: ArtUK

There are some items that don’t fit any particular category, such as 19th century copies of earlier Chinese cabinets (sometimes on hideously elaborate and inappropriate stands), a late 18th century cupboard decorated with thousands of tiny curls of coloured paper (filigree), late 18th century painted writing desks, and a staggeringly huge cabinet full of draws made with different types of wood; as a whole it is too big and ornate by modern standards, but the individual woods are very beautiful. There is also a room dedicated to Lord Leverhulme and his achievements, essentially the activities that paid for the village and the gallery, together with some more examples of his collecting interests, such as his ethnographic and ancient Egyptian items. Another room addresses the challenges of conservation.

Cabinet with multiple draws for collecting samples. 1830, but inspired by Thomas Chippendale (18th century)

On the missing list, it is most notable that there are very few Middle Eastern items, and that there are very few Medieval pieces, presumably reflecting Lord Lever’s taste. It was of particular interest that some of the pieces had been reworked once if not more times either to repair them, reconstruct missing elements or reinvent the original concept to make it more appealing to contemporary tastes. One of the Roman cineraria, for example, had lost its lid and had been provided with a new one in the 19th century, complete with twin Egyptian-style sphinxes.

Because preferences in art and decorative arts are so very personal, and some of the items are very much more 19th century than 21st century taste, not everything will appeal to everyone, but the skill represented by all items of all types is consistently excellent. A shift of focus from a complete piece of furniture to the individual components that make it up not only help to reveal that skill that went into an object, but also draw attention to themes, symbols and ideas that were built into these otherwise functional items.

A fairly disastrous mismatch of styles. The Dutch cabinet, inspired by Japanese art, dates to 1690. It rests on a an over-elaborately decorative baroque stand, dating to c.1680, inspired by Louis XIV solid silver furniture from Versailles

Some of the rooms have received significant investment since I was last at the museum around a decade ago, with modern displays, excellent lighting and good information boards. My impression is that there are fewer items on display in the Chinese and Wedgwood rooms, but that the focus on quality and representative types means that visitors are able to fully digest the collection without being overwhelmed by the sheer volume.

Some of the rooms have received significant investment since I was last at the museum around a decade ago, with modern displays, excellent lighting and good information boards. My impression is that there are fewer items on display in the Chinese and Wedgwood rooms, but that the focus on quality and representative types means that visitors are able to fully digest the collection without being overwhelmed by the sheer volume.

Perhaps more than anything else, the Lady Lever Art Gallery is an insight into the self-conscious 19th century perception of the world, including its values, hopes and ambitions. As one of the information boards points out, although Lever was a brilliant and in many ways an admirable man, he was also part of the story of colonization, with interests in the Belgian Congo. This aspect of his activities is now a new field of research at the gallery, helping to place the story of Lord Lever and his commercial and philanthropic activities into a more global and sometimes troubling context.

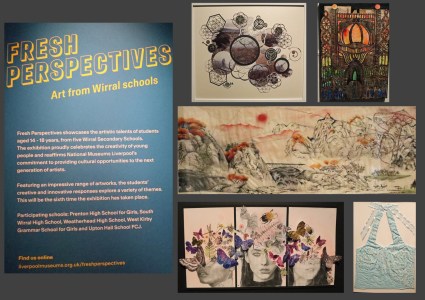

Click to enlarge. Artworks in the “Fresh Perspectives” exhibition. Clockwise from top left: Snowden Through a Lens by Jack Thompson; Gaudi in Paint by Freya Kennedy; Japanese Landscape by Millie Lawrensen Beckett; Seafoam Seaside by Isabelle Stockdale; Triptych by Indy Evans

The gallery often has special exhibitions, and these are worth watching out for on the gallery’s What’s On web page. At the moment there is a really thought-provoking exhibition, Fresh Perspectives (on until 27th Apr 2025), a tri-annual exhibition of inspiring artworks by young people from Wirral secondary schools. Julian and I chatted a lot as we were going around this about the differences between how art is clearly being taught in these schools and our own experiences of school art classes. As a professional artist, Julian was particularly impressed with how students are being encouraged to explore a wide range of approaches and express themselves using non-verbal methods. Here there is a lot of mixed-media being used in hugely creative and imaginative ways to produce some truly original artworks. There is a lot of inventive portraiture, but some of the semi-abstract pieces are particularly interesting, featuring multi-cultural themes and the use of overlays to provide focused viewpoints. It was heartening to see that even those who might not be able to draw were enabled to express themselves using other media to assemble evocative, expressive artworks. It is an absolutely excellent initiative, and we both found it truly inspiring. The exhibition also provides the gallery with a very modern component that it otherwise lacks (for obvious reasons!).

William Hesketh Lever. Source: Wikipedia

Check the gallery’s web page on the National Museums Liverpool website for opening times and other information. Access to the main collection is free of charge, but some special exhibitions may be charged for. You can preview some of the works on display, and read some articles about objects in the collection on the Collections page. Note that the website is one of those maddening matryoshka (nested Russian doll) affairs, with multiple museums nested within a general museums website, and it is very easy to find yourself clicking on the wrong thing and finding yourself going off the Lady Lever gallery pages and ending up somewhere else within the general museums website.

There is a terrific coffee shop in the basement, which does a range of sticky buns and cakes, breakfasts and lunches, and serves a range of hot and cold drinks (I can recommend the excellent latte), and where Julian and I set the worlds of decorative and fine arts to rights. It was interesting how not only the objects in Lord Lever’s collection but Lord Lever himself dominated many aspects of the conversation. The shop sells souvenirs, books, greetings cards, postcards, etc, and is beautifully presented.

Overall, a great visit.

English chest c.1600-1625 (Jacobean). Oak inlaid with holly, rosewood, fruitwoods, and possibly sycamore and holly.

Detail of the above chest: