This is the second part of my post about the background to English lunatic asylums, prior to focusing on the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum in Chester. To make the pages manageable, I have divided part 1, looking at the mental health background to the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum and other lunatic asylums into two. Part 1.1 was posted here a few minutes ago. Part 1.2 carries on below, following directly from part 1.1. A version of parts 1.1 and 1.2,without images, can be downloaded as a single PDF here (27 pages of A4) Sources and references for all posts can be found here.

Part 2 will focus on the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum at Upton in Chester and will be posted in the next month or so, when I’ve sorted out the images.

Timeline of reform after 1830

After the opening of a number of public asylums in the early 1800s, including the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum in Chester in 1829, several others began to be erected, including those in Dorset, Leicestershire, Shropshire and Montgomery and Devon, all by 1845, the year in which the County Asylums Act was passed. Private asylums still outnumbered county and charity asylums, some small and catering for a handful of patients, whilst others like and Ticehurst in Sussex (opened 1792) the purpose-built Brislington House near Bristol (opened 1806) were fully comparable in size to county asylums.

The most important innovation in the early 19th century had been the “moral treatment” that had been introduced by Philippe Pinet in Paris and by William Tuke in York, was influential on other asylum owners and designers. One of the most innovative of these was Methodist Dr William Ellis. Having learned the practice of moral treatment at the Sculcoates Refuge in Hull, in 1817 he was employed as superintendent at West Riding Pauper Asylum at Wakefield, with his wife Mildred as matron, where he practised the same approaches. His successes led to his appointment at the new Hanwell Asylum in Middlesex in 1832, with his wife again employed as matron. In each case patients were exposed to conditions that emulated family life and the manners of polite society, with treatment consisting of activities, entertainments and employment both indoors and out, using physical restraints only where strictly necessary. Social reformer Harriet Martineau, was impressed with how, when she visited, she saw a patient going to a garden to work with his tools in his hand, how a cheerful patient rolling in the grass with two other patients had been chained to her bed for seven years before arriving at Hanwell, and in shed in one of the gardens patients were cutting potatyes for seed “singing and amusing each other.” Ellis resigned in 1838 in a disagreement with the overseers of the asylum over their decision to extend the asylum for a much greater patient intake, convinced that his methods could not be successful in a much larger institution, as well as their plans to change how the asylum was managed.

In 1832 the Royal Commission carried out a survey of how the Poor Law was generally implemented throughout all counties, and who benefitted. The findings were published in 1834, and concluded that existing workhouses and almshouses were too sympathetic and generous, as well as too costly, to be sustainable. The report contained a long list of recommendations that set out to deter paupers from claiming relief by redefining the workhouse as a tool for reducing the costs of caring for the poor. The survey formed the basis of the new 1834 poor law.

In terms of social reform the new Poor Law, which was introduced to replace the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601, represented a backwards step. The Act, adding to the 1723 General Workhouse Act and the 1774 Madhouse Act, lead to even more lunatics being absorbed into workhouses, where all inmates were treated far more punitively then before. According to the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act (“the New Poor Law”) workhouses of a new type would be built to deter vagrancy and the dependency of able-bodied men, women and children on handouts, ensuring that only those who were suffering from desperate necessity would seek a workhouse place. The Act was introduced to reduce the cost of the poor by putting them to work in fixed indoor locations, removing beggars, vagrants and itinerant paupers from the streets, its main mechanism of which was the workhouse. However, although orphanages and infirmaries were also built, the workhouses were punitive places, built to discourage the idle from attending them. They provided deliberately uncomfortable living conditions, splitting of husbands from wives and parents from their children. To enable parishes to finance the new workhouses, the new poor law allowed for the creating of parish unions. Over 350 new workhouses were built within five years of the Act to cope with those who were unable or unwilling to find work.

In terms of social reform the new Poor Law, which was introduced to replace the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601, represented a backwards step. The Act, adding to the 1723 General Workhouse Act and the 1774 Madhouse Act, lead to even more lunatics being absorbed into workhouses, where all inmates were treated far more punitively then before. According to the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act (“the New Poor Law”) workhouses of a new type would be built to deter vagrancy and the dependency of able-bodied men, women and children on handouts, ensuring that only those who were suffering from desperate necessity would seek a workhouse place. The Act was introduced to reduce the cost of the poor by putting them to work in fixed indoor locations, removing beggars, vagrants and itinerant paupers from the streets, its main mechanism of which was the workhouse. However, although orphanages and infirmaries were also built, the workhouses were punitive places, built to discourage the idle from attending them. They provided deliberately uncomfortable living conditions, splitting of husbands from wives and parents from their children. To enable parishes to finance the new workhouses, the new poor law allowed for the creating of parish unions. Over 350 new workhouses were built within five years of the Act to cope with those who were unable or unwilling to find work.

The 1834 Act also laid down that dangerous lunatics, insane people and imbeciles were not to be kept in workhouses and should be moved to new asylums that should be built without delay, as per the Act of 1828, to receive them. In practice, however, partly because it cost less to house lunatics in workhouses than asylum, and partly because asylums were often overcrowded, an alarming number entered workhouses. In some workhouses special wards within workhouses for the insane were added, and these were often used as repositories for the mentally ill, as well as imbeciles and idiots, the debilitated elderly (particularly those suffering from dementia) and the physically disabled.

The Chester Union Workhouse in 1861, recorded on workhouses.org, included 29 long-term inmates (continuous living for five years or over) of whom nine (31.03%) were deemed to be of “weak mind” and two (6.9%) were “subject to fits” (the latter relevant because epilepsy was considered to be a form of insanity until the late 19th century). Interestingly, the incorporated union of Chester’s nine parishes was exempt from the 1834 act, and Chester did not accept a Chester new Poor Law Union until 1869. There is clearly a lot more work to be done in Chester between the lunatic asylum and its workhouses.

The 1820 Lincoln Asylum. By Elliott Simpson, CC BY-SA 2.0. Source: Wikipedia

New reformist practitioners continued to make their mark in the treatment of lunatics, mainly in private asylums for the wealthy, but also in the county asylums. In 1820 the subscription-funded Lincoln Lunatic Asylum was opened, and in 1837, under Edward Parker Charlesworth and Robert Gardiner Hill, became notable for being the first English asylum to formally abolish the use of mechanical devices for restraint, with the results recorded in the asylum’s annual reports. This approach was influenced by the death at the asylum in 1829 of patient William Scrivinger, who was strapped to his bed overnight in a straitjacket and was found dead from strangulation in the morning. In 1838 Robert Gardiner Hill, who became house surgeon at the asylum, delivered a lecture to The Mechanics’s Institute, Lincoln, advocating the care of the mentally ill without recourse to restraints, which was subsequently published and circulated and became influential on other asylum superintendents who were interested in treating symptoms rather than merely detaining patients.

Tabulated records of restraint from the Lincoln Lunatic Asylum in 1830 (click to enlarge). Wellcome Collection.

===

In 1839 John Conolly moved to Hanwell Asylum in Middlesex to take over from William Ellis as its third superintendent. As superintendent he took Ellis’s policy of only using restraints when unavoidable even further, following Robert Gardiner Hell, and in his first report from the asylum claimed that the banning of restraints, replaced by “kindness and firmness” had produced a much better environment for patients. He believed that supervision by specially trained attendants and nurses, consistent regimes and pleasant surroundings were essential. His treatment regime was reported by The Times on several occasions, an the asylum was visited by influential figures in society. Although many other alienists were sceptical about non-restraint, the positive publicity soon influenced other asylums who began to follow the lead originally set by Robert Gardiner Hill, but publicized by Conolly. Following his resignation from Hanwell in 1844, after a disagreement with the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy, Conolly published his latest opinions on the subject of managing lunacy. These included his 1847 The Construction and Government of Lunatic Asylums and Hospitals for the Insane and his 1856 The Treatment of the Insane without Mechanical Restraints. His 1849 A remonstrance with the Lord Chief Baron touching the case Nottidge versus Ripley clearly stated his belief that eccentricity, excessive passion, signs of moral failure, gambling what should not be tolerated, and any person’s behaviour that was “inconsistent with the comfort of society and their own welfare” were sufficient to merit certification and committal to an asylum. This position was one of intolerance to any behaviour that might contravene strict ideas of social conventions.

In 1839 John Conolly moved to Hanwell Asylum in Middlesex to take over from William Ellis as its third superintendent. As superintendent he took Ellis’s policy of only using restraints when unavoidable even further, following Robert Gardiner Hell, and in his first report from the asylum claimed that the banning of restraints, replaced by “kindness and firmness” had produced a much better environment for patients. He believed that supervision by specially trained attendants and nurses, consistent regimes and pleasant surroundings were essential. His treatment regime was reported by The Times on several occasions, an the asylum was visited by influential figures in society. Although many other alienists were sceptical about non-restraint, the positive publicity soon influenced other asylums who began to follow the lead originally set by Robert Gardiner Hill, but publicized by Conolly. Following his resignation from Hanwell in 1844, after a disagreement with the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy, Conolly published his latest opinions on the subject of managing lunacy. These included his 1847 The Construction and Government of Lunatic Asylums and Hospitals for the Insane and his 1856 The Treatment of the Insane without Mechanical Restraints. His 1849 A remonstrance with the Lord Chief Baron touching the case Nottidge versus Ripley clearly stated his belief that eccentricity, excessive passion, signs of moral failure, gambling what should not be tolerated, and any person’s behaviour that was “inconsistent with the comfort of society and their own welfare” were sufficient to merit certification and committal to an asylum. This position was one of intolerance to any behaviour that might contravene strict ideas of social conventions.

Male and female patient employment records at the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum for the year 1855 (click to enlarge) (Wellcome Collection).

The new forms of treatment that attempted to return people to society put great emphasis on the value of manual work, much like the influential 6th century Benedictine monastic ideal, so some asylums built and managed home farms in which patients worked, and indoors encouraged involvement in art, crafts, sewing of clothes and other items of use within the asylum, and help with the maintenance of the asylum buildings. Airing courts provided leisure access to fresh air and vegetation, and sporting activities were arranged. Indoor leisure activities included games, indoor sports, reading material, the ability to engage in art, music, dance and theatre, and there was in-house provision for access to religious guidance

The 1842 Poor Law Commissioners Act introduced by social reformer Lord Ashley (later Lord Shaftesbury), extended the authority of London’s Metropolitan Commissions in Lunacy to the entire country and expanded its staff. Its remit was extended for a trial three-year period to all types of care institution in all parts of England and Wales where lunatics might be held, and this in turn led to the 1844 report of the Metropolitan Commission to the Lord Chancellor. This report described poor conditions and treatment, and expressed concerns about illicit certification and the continued incarceration of those who had recovered.

An indication of how much work still needed to be done to care for the insane was an article published in 1834 by Harriet Martineau, one of Britain’s first sociologists, who asked whether lunatic asylums really needed to be as dreadful as they so often were, contrasting it with the pioneering attitude of Dr William Ellis and his wife Mildred at the new Hanwell Lunatic Asylum, which opened in 1831:

It is commonly agreed that the most deplorable spectacle which society presents, is that of a receptacle for the insane. In pauper asylums we see chains and strait-waistcoats, – three or four half-naked creatures thrust into a chamber filled with straw, to exasperate each other with their clamour and attempts at violence; or else gibbering in idleness, or moping in solitude. In private asylums, where the rich patients are supposed to be well taken care of in proportion to the quantity of money expended on their account, there is as much idleness, moping, raving, exasperating infliction, and destitution of sympathy, though the horror is attempted to be veiled by a more decent arrangement of externals. Must these things be? (my italics).

A two year investigation by the Metropolitan Lunacy Commissioners was followed by the 1844 Report to the Lord Chancellor which, like its predecessors, highlighted the abysmal conditions in many of the establishments that that housed lunatics: “Twenty-one counties in England and Wales had neither public nor private asylum. Profiteering was rife in the private sector; such public asylums as existed were often defective in terms of site, design or accommodation” [Mellett 1981]. The 1844 report seems to have had rather more significant impact than some of its predecessors, timed as it was with Lord Ashley’s continued and vigorous campaigning to provide for pauper lunatics. The Socialist Health Association records that in 1844 there were around 20,600 lunatics in some form of institution or private care in England and Wales, of whom only 3800 were private patients. Over 16,800 were classified as paupers.

Edward Wakefield’s 1815 statement about the value of recommending a change to the law to make new asylums compulsory. Source: Wellcome Collection

In 1845, following the 1844 report, Lord Ashley was able to push through the important Lunacy Act and the County Asylum Act. Importantly, every county was given compulsory responsibility for the provision of a county asylum funded by rates, instead of making it optional as in the 1808 Wynn’s Law. This was a measure that Edward Wakefield, reporting to the 1815 Select Committee had suggested be implemented, and it had taken 30 years for the recommendation to be acted upon. The Act required the transfer of mentally ill people (defined as lunatics and idiots) from workhouses, where over 6000 were recorded in 1847, to these new or existing asylums. It became a legal requirement that both a new Board of Commissioners for Lunacy and regional Justices throughout England and Wales should regularly visit places where lunatics were held, in prisons and workhouses as well as hospitals and both the old and new asylums, for both private and public institutions. Locally appointed Committees of Visitors would oversee the ongoing operation of asylums, and an annual report would be submitted to the Lunacy Commissioners. It was now also a legal requirement that asylums record admissions with basic demographic information about the patient, the reason for admission, details of the disorder, treatments and ultimate outcomes (i.e. discharge or death, including suicide). These were to be inspected at least annually by the Commissioners and regional Justices. In practice, the Act was not supported with funding or resources, and many of its measures proved difficult to implement and enforce, although it was responsible for the growing number of asylums throughout England and Wales. Again, improvements to certification processes were made. In 1847, reporting on their progress, the Commissioners noted how their workload had expanded, emphasising their role as a central resource for asylums:

We have found it necessary to carry on an extensive correspondence with numerous parties, some demanding· the interposition of our authority, in reference to cases of supposed abuse; many requiring information, and many others neglecting or misinterpreting· the salutary provisions of the Acts of Parliament; and in the course of this correspondence, numerous questions (some of much nicety and difficulty) have been submitted to us; we have also found it necessary to enter into long and difficult investigations.

The commissioners were undoubtedly patting themselves on the back in this piece of text, demonstrating the value of their new role, but the rest of the report suggests that since the passing of the 1845 Act they had been very busy assessing the network of public and private asylums for which they were now responsible, gathering extensive amounts of data to inform their decisions.

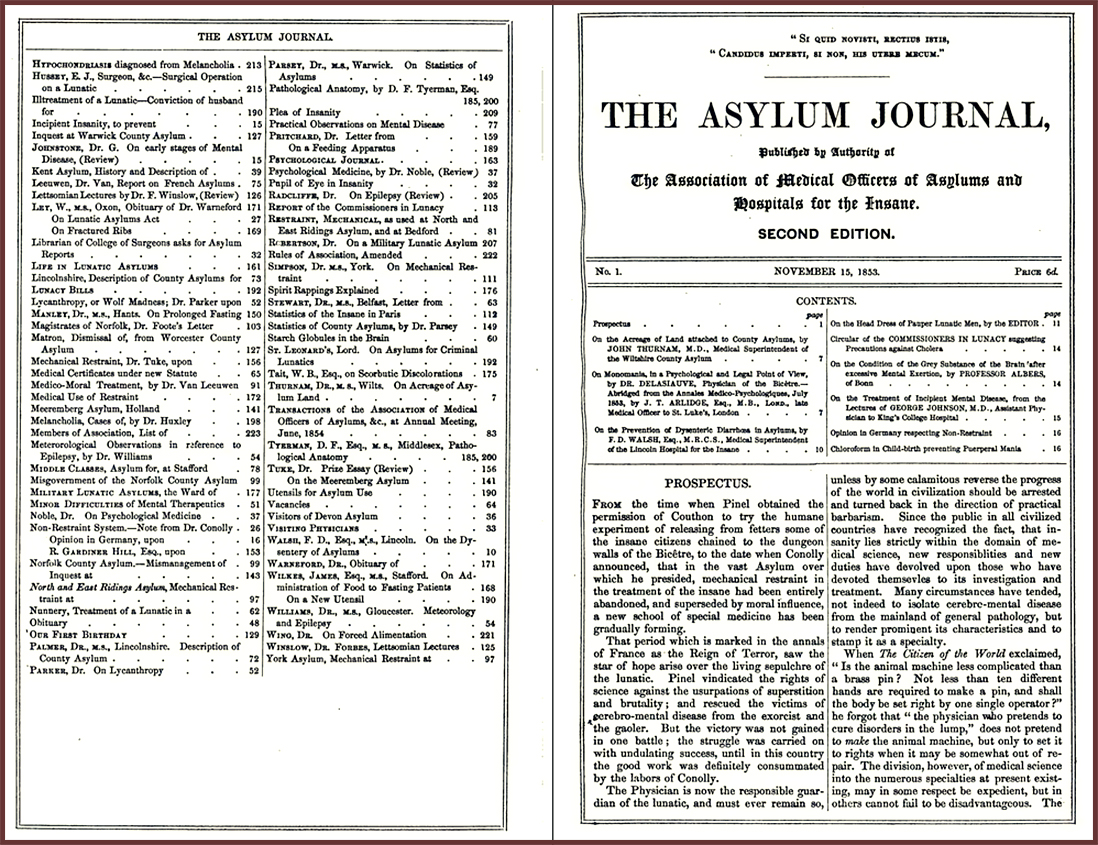

In 1853 John Bucknill (1817–1897) became the first editor of the Asylum Journal, which became the Journal of Mental Science. Bucknill held the position until 1862. The Journal eventually became the British Journal of Psychiatry and is still publishing today. This provided a forum for interested parties, mainly those connected with asylums, to put forward their ideas and instigate discussions. Ideas about madness and lunatic asylums also filtered into the British Medical Journal.

Asylum Journal 1855. Source: Internet Archive

===

Another set of laws were introduced with the intention of improving matters throughout the second half of the 19th century. The 1853 Lunacy Amendment Act outlawed hearsay evidence from the process of certification, meaning that doctors were no longer able to depend on the accounts of those who were asking for patients to be admitted to asylums. The certification process required that doctors only included behaviour that they had themselves observed at first hand, another measure towards prevention of wrongful confinement. The 1862 Lunacy Act enabled patients who had received care for mental illness in the past to enter asylums on a voluntary basis to receive treatment. Special permission had to be sought from two lunacy commissioners, but this recognized that the treatment of mental health should not be exclusively enforced and custodial. It also allowed for greater fluidity of transfer of patients between asylums and workhouses. The Annual Report of the Lunacy Commission for the same year noted that physical restraints were no longer in common use and that isolation was preferred as a viable alternative. In 1867 the Metropolitan Poor Bill was designed to recognize harmless “imbeciles”, those with learning difficulties in London workhouses and asylums, and to provide them with specialized establishments. In 1874 the rising costs of asylum management were recognized by the government who introduced a grant allocating 4 shillings per week per person sent to the asylum. This presumably also assisted with moving appropriate inmates from workhouses to asylums.

Unfortunately none of the above measures were successful in introducing genuine state-sponsored social responsibility and reform. As late in the 19th century as 1873 the British Medical Association expressed its views on the existing state of asylums:

Unfortunately none of the above measures were successful in introducing genuine state-sponsored social responsibility and reform. As late in the 19th century as 1873 the British Medical Association expressed its views on the existing state of asylums:

There are no public institutions which lie so open to attack as lunatic asylums. They are necessary evils; they interfere with the liberty of the subject; they are costly in erection and maintenance; and they are, as a rule, managed with doors more closely shut than those of other hospitals. There also hangs about them in the mind of the public an air of mystery, and the memory of bygone evils is by no means erase. When all these factors of unpopularity are taken into account, it is not difficult to see why the complaints of those who have been subjected to their discipline are listened to with avidity. [BMA August 2nd 1873, p.120]

Sadly, as the century advanced and passed into the 20th century, the number of admissions into asylums increased and the earlier idealistic and more personalized approaches became impossible to implement. The 29th Annual Local Government Report of 1900 stated that in 1860 50% of insane paupers were in county and borough asylums, and 25% of them in workhouses. By 1900 there were 75% in asylums and just under 20% in workhouses.

xxx

Public anxiety about lunatic asylums in the mid-late 19th century

Louisa Lowe, incarcerated even though later judged to be completely sane. Source: a digitized copy of Blighted Life, in the Wellcome Collection

Whilst the role of lunatic asylums was widely discussed in Victorian medical journals and works produced by alienists, each promoting certain methodological and ideological approaches, there were also publications that spoke to the general public, representing concerns with the alienist profession and describing clear infringements of what we would now think of as the human rights of those who had been illicitly incarcerated. Wrongful incarcerations fell into two main categories. First, there were those individuals who had been incarcerated forcibly when sane, sometimes as the result of collusion between family members and medical professionals. Secondly there were those who had been admitted to an asylum under a legitimate certificate, but continued to be detained long after they had recovered their senses. Part of the problem lay in what did or did not qualify as sanity but, as discussed above, there were also cases of malicious incarceration and corrupt collusion for financial advantage.

There were two primary channels of information about such cases to the general public. Both national and local media took up the stories of those who had been illicitly confined in lunatic asylums, whilst some of the victims published their own accounts. Examples of the latter are John Perceval’s A narrative of the treatment experienced by a gentleman during a state of mental derangement (1840), Rosina Bulwer-Lytton’s A Blighted Life (1880) and Louisa Lowe’s The Bastilles of England, Or The Lunacy Laws at Work (1883). Some publications were anonymous, former mad-house inmates fearing derision or stigma. One author, “A Sane Patient,” wrote My Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum (1879), and another was written by “A Clerical Ex-Lunatic:” The private asylum: how I got in an out: an autobiography (1889). As well as describing the circumstances under which they had been admitted and in which they lived, some also urged government change to existing laws.

News article excerpt about Lawrence Ruck in The Leader, no.440, August 28th 1858, p.862. Source: Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition

Although there were exceptions, the means by which the media became aware of such cases was largely via formal inquisitions. In 1858-1859 there were four cases that caused a media sensation and a public panic about illegitimate certification: Rosina Bulwer-Lytton, Mary Jane Hepworth, Reverend William Leach and Lawrence Ruck. Inquisitions were legal mechanisms by which those held in private asylums could apply for permission to take their cases in front of a judge and jury to attempt to prove their sanity. Witnesses could be called to give testimony for or against a patient’s sanity, both personal and professional. These were very expensive and the cost fell on the applicant, so was available only to the very wealthy. Because these people often belonged to elite families or were associated with public figures, they could be of great public interest. Inquisitions were held in public, in any venue large enough to accommodate them, in coffee houses, bars and taverns, and any member of the general public or media was free to attend. Juries were men, often magistrates or others who were sufficiently educated to assess both medical and legal arguments. In the cases of Bulwer-Lytton, Hepworth, Leach and Ruck, all four had been confined in asylums, but during inquisition had been judged sane. Rosina Bulwer-Lytton had a particular gift for publicity and succeeded in winning many newspaper publications to her side to publicize her grievances. The highly publicized scenario where a family member, colluding with an asylum owner and sent attendants to bundle a sane victim into a carriage to be locked up, their basic human rights denied them, caused real public anxiety.

Report of the Alleged Lunatics’ Friend Society 1851. Source for report: Wellcome Collection

The newspaper publications and first-hand accounts about individual cases were supplemented by the work of pressure groups. Three groups were formed to promote the causes of patients in asylums, more or less consecutively, all started by those who had direct experience of illegal detention in lunatic asylums: The Alleged Lunatics’ Friends Society (an informal grouping until 1845 when they became organized), the Lunacy Law Reform Association, and its splinter group The Lunacy Law Amendment Society. At the same time, Georgina Weldon attracted many followers in her campaign against illegal incarceration and detainment in asylums, having gone into hiding when her estranged husband attempted to have her committed. Whist in hiding she was declared sane by two independent physicians. All these activists wrote letters to influential people, took out newspaper adverts, distributed pamphlets and spoke extensively in public in attempts to influence government action to reform lunacy laws. Although they were rarely successful at pushing through legal reform, they were very good at generating publicity for their causes, drawing attention to the financial motivations of both those who might benefit from certifying a relative and the asylums admitting them, and the callous tyranny of some of the asylum owners and staff. They also acted to take up individual cases where sane people remained locked up in asylums.

Inevitably, in spite of attempts to force through legal and social reform, changes in the law always lagged behind the need for reform. For every energetic reformer there were many more places that continued to follow easier, less labour-intensive means of confinement, and although individual reformers and medical representatives attempted to improve asylum care, there were continuing problems of unnecessary and illegal incarceration and detainment, sometimes as a result of collusion between relatives and asylum owners, causing ongoing anxiety in contemporary society.

xxx

The criminally insane

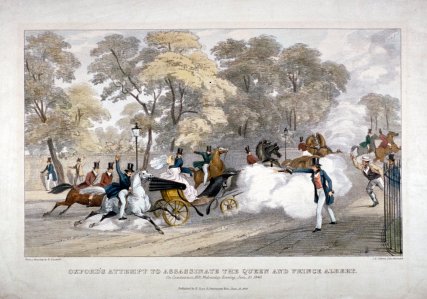

Lithograph by JR Jobbins in 1840 showing the assassination attempt by Edward Oxford on Queen Victoria. Source: Meisterdrucke

In 1800 when James Hadfield attempted to assassinate George III in the belief that the death of the king would initiate the Second Coming of the Messiah, he was charged with treason. However he was judged to be non compos mentis (not in his right mind) due to severe head injuries incurred during his service as a soldier. This verdict of insanity was followed by the the Criminal Lunatics Act, which required that criminal lunatics should be detained in county jails, and lead to the addition of a new criminal wing be Bethlem to house the criminally insane. A number of high profile cases followed, and in 1840 Edward Oxford fired a pistol at Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as they were travelling in an open carriage on Constitution Hill in London, and although he was tried for high treason, was found not guilty by reason of insanity. He was sent to the criminal wing at Bethlem.

Daniel M’Naghten photographed by Henry Hering in around 1856. Source: Bethlehem Hospital Museum Archives via Wikipedia

A decisive case was that of Daniel M’Naghten who, in 1843, attempted to kill Prime Minister Robert Peel, but mistook Peel’s secretary for the Prime Minister, shooting and killing him. M’Naghten suffered from paranoid delusions, thinking that the Tories were persecuting him and were planning to murder him. He was acquitted on the basis of insanity and confined to Bethlem asylum. This lead to the M’Naghten Rule (or M’Naghten Test) which provided criteria for assessing whether or not someone was insane at the time that a serious crime was committed, to assess whether or not someone was criminal liable. Only when the test has been completed in all its parts can a person be deemed to be criminally insane.

One of the best known 19th century inmates of both Bethlem was was the remarkable professional artist Richard Dadd R.A., who was incarcerated first in the ward for the criminally insane in Bethlem in 1843. Dadd, after exhibiting signs of violent and delusional behaviour when travelling in the Middle East went to stay with his parents to recover but, believing that he was acting under the orders of the Egyptian God Osiris, murdered his father whom he was convinced was possessed by the Devil.

Richard Dadd, painting whilst incarcerated in an asylum in 1856. Source: Wikipedia

These cases paved the way for the establishment of the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, which opened in 1863 in Berkshire, and which remains in use today. Oxford, M’Naghten and Dadd were all transferred to Broadmoor in 1864. M’Naghten died in 1865 but Dadd continued to paint throughout there until his death in 1886 at the age of 68. Edward Oxford, who showed no ongoing signs of insanity, was offered the opportunity to be relocated to Australia in 1867, and duly took up the offer, settling, marrying and living out his life in Melbourne, later publishing a book about the city.

Much of the intention of earlier laws in this respect was re-formalized in the Trial of Lunatics Act of 1883, in which any offence committed whilst a person was deemed to be insane, and therefore according to the law not responsible for his actions at the time when the act was committed, a special verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity should be returned. This law was updated several times, most recently in 1991.

Day room for male patients at the Asylum for Criminal Lunatics, Broadmoor, Sandhurst, Berkshire. Source: Wellcome Collection

A broken system

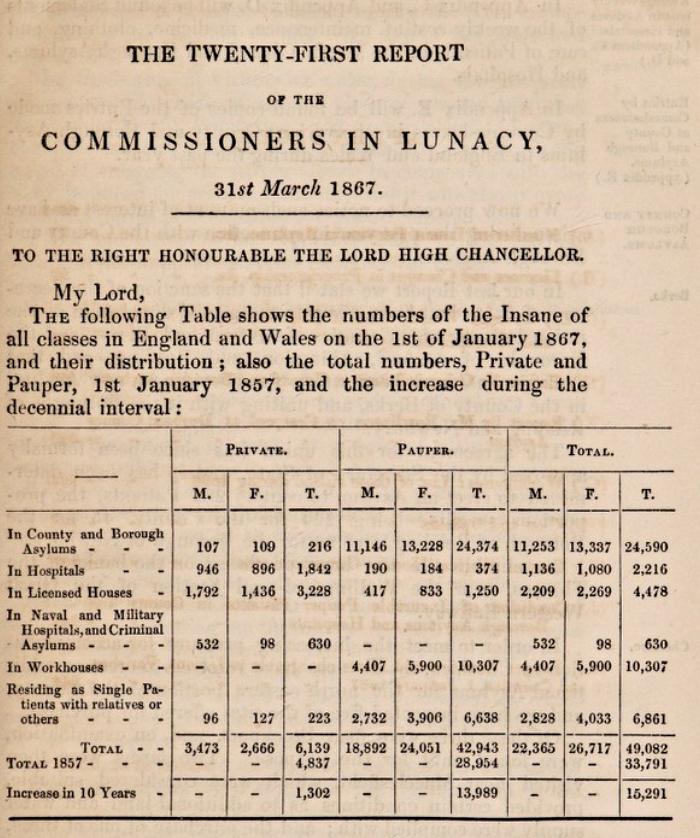

Excerpt for a page from the 21st Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy for 1866, published in 1867. Source: Wellcome Collection

In the later half of the 19th century, it was becoming clear that the optimism of both medical and legal professions the 1840s was dwindling fast, and that the asylum system was failing to keep up with demand. The 21st Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy in 1867 indicated that 90% of patients in public asylums were considered to be incurable. Writing only three years later in 1870, Dr Andrew Wynter, former editor of the British Medical Journal, commented that “Our whole scheme for the cure of lunatics has utterly broken down.” Although it was convenient to hold large numbers in facilities where they could be dealt with in a consistent and organized way, the numbers of those who entered far exceeded the numbers of those who left. Overcrowding was a serious problem for most public. The emphasis inevitably shifted from treatment and cure to containment, order and bureaucracy. This succeeded in dividing lunatics from society, but did not address the root cause of the the problem – the analysis and cure of mental illness. Those who might have been treated and restored to their families were lost in the sheer volume of inmates who required maintenance and management. Wynter referred to this as “brick and mortar humanity.”

Plan for Caterham and Leavesden 1868, both serving the London area. Both were opened by the Metropolitan Asylums Board in 1870, and within five years demand far exceeded capacity, requiring new building works to accommodate the influx of new patients . Source: Wellcome Collection

There were only two practical solutions to overcrowding in asylums. The first was to return non-violent patients to their families or to send them to workhouses. The second was to expand existing asylum buildings and facilities and to build new asylums. Although workhouses continued to take in lunatics and idiots, expansion and new building were the most frequently adopted solutions. It is to this period that the first of the vast dedicated developments were built, with their own water and gas works, their own fire brigades, cemeteries and other urban-type facilities. These were located in rural locations, where asylums could be conveniently separated from the rest of society, and where land was relatively cheap. The earliest examples of these vast enterprises were built to serve London and its environs, and include Colney Hatch in Middlesex (opened in 1849 for 1000 patients), Leavesden and Caterham (both opened in 1870 for 2000 patients each), Caterham, and Claybury County Asylum (opened in 1894, also for 2000 patients).

Claybury County Asylum, now converted into apartments. Source: Wikipedia

It was not until nine years later that the 1886 Idiots Act created specialist asylums for individuals with learning difficulties beyond the London area. Important distinctions were made between lunatics on the one hand and harmless idiots and imbeciles (those with learning difficulties) on the other. The intention was to take the opportunity to care for them and provide basic education and training so that idiots were treated neither as lunatics that needed to be confined nor as indigent vagrants. Following this, the 1890 Lunacy Act the certification of alleged lunatics was moved to the jurisdiction magistrates as well as doctors. It also made the provision of free mental healthcare available, but as the majority of the population could only access free psychiatric care if they were certified insane and agreed to be admitted to an asylum, the stigma of certification and the requirement for confinement were significant deterrents to people volunteering to receive the help they needed. More than any previous law, the 1890 Act helped to prevent medical collusion to incarcerate patients wrongfully. Whereas only medical certification had been required before, a civic official such as a magistrate or Justice of the Peace was now required to certify madness. The Act also took measures to prevent the licensing of new asylums, aiming to inhibit the further licensing of private asylums, which it was hoped would lead to the eventual demise of the private asylum.

An inspection of the formerly progressive Hanwell in 1893 described depressing conditions, concluding that it would be surprising if any of the patients were to recover given the type of care they were receiving in fairly dismal surroundings. Even more regrettably, the untested idea that mental illness could be passed from one generation to the next fed into the horrible theory of eugenics. New surveys continued to be carried out, reports continued to be submitted and new laws continued to be introduced, modified and implemented, but it is a sad fact that neither medicine nor the government, via changes to the law, managed to provide convincing support for a growing section of society that was still not well-understood.

===

After the Victorian period

Graphic to accompany the one-man play Shell Shock, performed at the National Army Museum to mark Mental Health Awareness Week in 2019. Source: National Army Museum

I have not ventured into post-Victorian approaches to mental health in this post, but it was very far from a story of continual improvement of care and cure. There was still a very long way to go to even begin an understanding mental illness, and to standardize, in a scientific way, the treatment mental illness in psychiatric units. Sigmund Freud’s end-of-century theories of psychology were squabbled over for decades. The First World War’s executions for “shell shock” as a judgement of cowardice remain deeply shaming. In the inter-war years psychiatrists began to take a more experimental and interventionist approach to treating mental illness. Several new so-called “heroic” physical therapies were introduced, based on the belief that mental illness had a physical basis in the nervous system or the brain. These included insulin coma, chemical shock, electro-convulsive shock therapies and, most radically interventionist, lobotomization. Egas Maniz’s experiments with prefrontal lobotomy remain profoundly disturbing.

The abandoned Denbigh Lunatic Asylum. Photograph by Steve R. Bishop. Source: Everywhere from Where You are Not

It will come as no surprise to those who follow the news that there are still serious problems, not merely in official provision of mental health care, but in care homes for the elderly, including those recuperating and convalescing, and those who had been persuaded to hand over power of attorney. There were dreadful examples of people being released from long-term incarceration in the 1950s and 60s who had been admitted for minor criminality and socially disruptive behaviour, and although they had become institutionalized were found to be completely sane. The use of vast repositories for the mentally unwell was abandoned without, however, a clear strategy for handling those who still needed help. This was followed by a policy of caring for the mentally unwell within the community, pushed through during the 1980s, which often failed to provide families and local care centres with sufficient resources to make this fully viable, placing great strain on families and support mechanisms. The tyranny of some institutions was revealed in a number of scandals and was a theme explored in relatively modern times in the 1975 film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Documentaries in care homes in recent times demonstrate how this problem still persists in some places.

Ancona House. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services unit at the Countess of Chester Hospital, Chester

Today the madhouse or lunatic asylum has become a psychiatric hospital or a psychiatric unit in a general hospital for those with manageable symptoms, or a specialist secure facility for the violent and criminally insane. In the Victorian period medical understanding and psychiatric ideas were only beginning to be proposed and tested, and this continued well into the Edwardian period and beyond, with medicine and the law both playing important parts in how mental illness and suicide were understood, diagnosed and treated. The research remains ongoing. There is still no viable solution, or set of solutions, to the problem of coping with mental illnesses. The subject of how to care for those suffering from mental illness is far from resolved.

===

Final Comments on parts 1.1 and part 1.2

William Tuke’s “The Retreat” in around 1796. Source: Wikipedia

In spite of being divided into two parts to make it easier to digest, this quick and dirty summary of the state of mental healthcare in the 18th and 19th centuries inevitably smooths out some of the kinks in that often convoluted story, over-simplifying some of the many subtleties. This account represents a very short summary of a very complex topic.

From the late 18th century mental illness represented a growing issue for a society that was developing a broad social conscience. In spite of many reforms to poor laws and a number of new Acts of Parliament to govern asylums, governments were slow to respond to either public pressure or their own specially commissioned reports, and stories of unlawful detainment in some places and frightful conditions in others failed to produce change that was both meaningful and timely. The role of workhouses in the handling of the mentally ill continued to be important, with patients shared between workhouses, workhouse infirmaries and asylums, in spite of legislation designed to make the responsibilities of each much more transparent, which is an area that needs to be much better understood. It was only towards the end of the 19th century that those with learning difficulties, termed imbeciles and idiots, were seriously treated in the law as a separate problem requiring different types of care. The topic of children in lunatic asylums is not much discussed, but records show that at least some were admitted, as they were to workhouses.

Sometimes those who were supposed to represent the pinnacle of care and reform are described with a rose-tinted filter. For example, Edward Long Fox and his sons, running one of the most expensive private asylums in the country, were accused in the writings of patient John Perceval, son of the murdered prime minister Spencer Perceval, of incarcerating their more troublesome patients in truly dreadful conditions where they were subjected to beatings, threats, manacles, strait-vests, freezing water baths and other punishments and indignities. The alienist John Conolly, a national figurehead of ethical and human approaches, was found guilty in court of taking money for signing legally binding certificates that retained patients in private asylums to which he was employed as a paid consultant. One of these patients was found, by jury to be sane and the investigation highlighted the risk of consultants being paid by asylums for certifying patients. He also often took credit in public for introducing non-restraint in England, in fact an innovation of Robert Gardiner Hill at Lincoln, and at Hanwell asylum had a very low cure rate. Another example is Lord Ashley, later Lord Shaftesbury, generally and fairly acknowledged as an important voice for mental healthcare reform but sometimes remarkably intransigent. He often blocked or delayed changes that would have made important differences that would have lead to improved quality of life and greater transparency and justice in the asylum system. This was a particular problem given that Ashley had been elected the lifetime head of the Commission for Lunacy, a position that he did indeed hold until his death in 1885.

By the end of the century the dream of personalized care of the mentally ill by engaging them in social activities within attractive contexts was largely abandoned. The “moral treatment” approach had depended not only on sufficient numbers of attendants to manage patients with kindness and empathy, but those who had a genuine interest in caring and treating. The 1870 Annual Report of the Lunacy Commission recorded that 122 attendants had been dismissed in 1869 for manhandling patients roughly or violently, and it is not at all surprising that as new patients were admitted in increasing numbers, the sheer volume proved difficult to manage:

The number of people certified as ‘insane’ soared. The asylum created demand for its own services. Less and less people ever left, and more and more arrived. In 1806 the average asylum housed 115 patients. By 1900 the average was over 1,000. Earlier optimism that people could be cured disappeared. The asylum became simply a place of confinement. [Disability in Time and Place, Historic England, Simon Jarrett]

Leavesden Hospital in Abbots Langley, Herts., opened 1870. Source: Leavesden Hospital

Governments as well a local organizations began to invest in creating larger institutional solutions for paupers whose symptoms indicated the sort of social deviance and/or danger to self that could not be countenanced without intervention. However. the recognition of mental illness and the acceptance that it should be handled by the state caused its own problems as more people were incarcerated and management of mental illness became, like contemporary prisons, more of an issue of how to maintain order than how to provide cures. Unlike most prison sentences, there was no release date for mental patients, who could be held indefinitely and sometimes were. An indication of how urban areas in Britain were overwhelmed by demand was the new Metropolitan District Asylum built between 1868 and 1870 as Leavesden Hospital in Hertfordshire, which was designed to house 1500 patients, after which it continued to expand to cope with the ever growing need to provide care for the mentally ill. Like other asylums of this period, it is more like a small town than a hospital. Sadly, many asylums once again became associated with confinement and bureaucracy rather than attempts at cure and rehabilitation.

The perception of mentally ill people changed over the course of the Victorian and Edwardian periods as psychiatry developed as a specialist branch of medicine, swinging between biological, congenital and neurological explanations on the one hand and emotional-psychological explanations on the other. The degree of subjectivity lead inevitably to disagreement and contradictory opinions, with very little indication of how to choose between the variety of different ideas held in different asylums. The legacy of 19th century mental health medicine, law and care seems to be one of a continued struggle to fully comprehend the complexities of mental illness or to devise suitable ways of treating them sustainably. As Mike Jay says in his book This Way Madness Lies, “While the asylum as an institution is now largely consigned to the past, many of the questions it struggled so hard to address still persist.”===

Click here for the references for this post

Full 1-hour documentary about the situation within mental asylums at the time of the closure of many of them

Out of Sight, Out of Mind – The Leavesden Asylum Story

Leavesden Hospital History Association

This is an insightful first part of a series that sheds much-needed light on the history of Cheshire Lunatic Asylum. Your exploration of the development of asylums during this period is both informative and evocative. The way you weave together historical context with the human side of the asylum’s legacy makes for a compelling and thought-provoking read. I look forward to the continuation of this series!

LikeLike

Dear Patricia. Thank you so much! I am currently working my way through the reports for the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum, with a view to finishing the current piece of work in the next couple of weeks. It has been really compelling to learn about how asylums began to become an important aspect of healthcare management both in terms of national law and locally, on the ground. A steep learning curve, but very rewarding. The Cheshire Lunatic Asylum seems to have been one of the better run examples in the late 19th century, with a genuine intention to treat and cure patients wherever possible. I am quite staggered at how every year new building works were required to cope with rising numbers of patients being referred to the asylum.

LikeLike