Beginning with nine voluntary institutions, the asylum movement rolled across the 19th century English landscape like an avalanche gathering pace. The ‘mentally unsound’ were moved in ever greater numbers from their communities to these institutions. From 1808, parliament authorised publicly funded asylums for ‘pauper lunatics’, and 20 were built. From 1845 it became compulsory for counties to build asylums, and a Lunacy Commission was set up to monitor them. By the end of the century there were as many as 120 new asylums in England and Wales, housing more than 100,000 people.

Historic England: The Growth of the Asylum – a Parallel World

==

Introduction

As part of my ongoing series looking at Overleigh Cemetery, I asked Christine Kemp of the Friends of Overleigh Cemetery about the suicides she knew of in Overleigh Old and New Cemeteries. In the 19th century suicide was more often than not deemed to be the result of temporary insanity. Looking into how suicide was handled in the 19th century lead me to the discovery, probably very familiar to most Chester residents, that there had been a “lunatic asylum” where the enormous site of the Countess of Chester Hospital is now located at Upton.

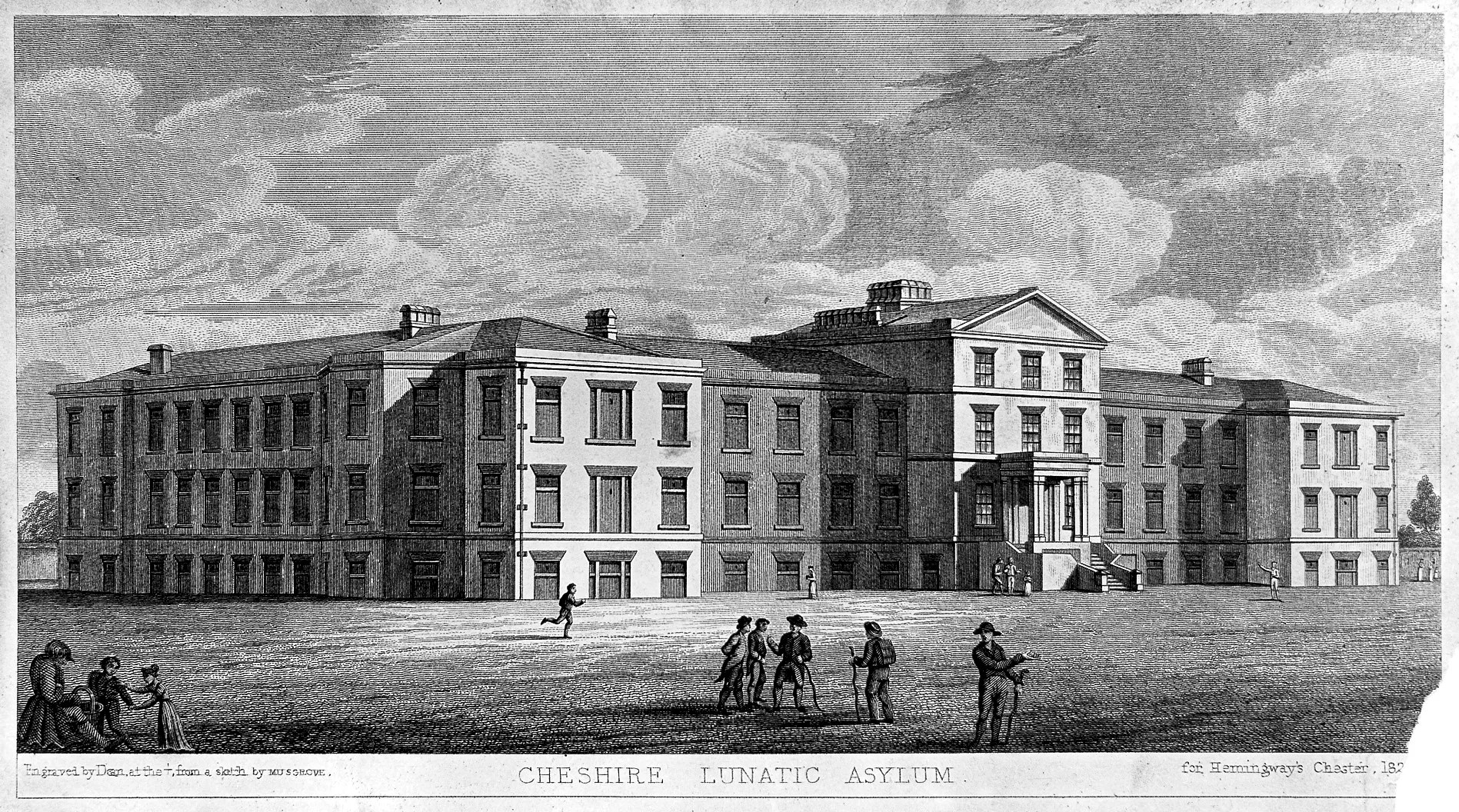

The Cheshire Lunatic Asylum was a public institution established to house pauper lunatics as well as a limited number of paying private patients in 1829. The asylum opened on a 10 acre site in 1829 to accommodate 45 women and 45 men, reflecting the fairly even numbers of both at asylums in the 19th century. It grew throughout the 19th century and eventually occupied a significant area of over more than 55 acres.

The exterior of the earliest building remains in situ, and has the appearance of an elegant and stately Georgian-style building with a small Classical portico, looking very much more like a the remnant of a country estate than the intimidating prison-type establishment that I had been expecting. An elegant façade was typical of 19th century asylums. Today the asylum building is still an active part of the Countess of Chester Hospital, officially named “The 1829 Building” (Grade 2 listed), housing a number of departments including Adult Mental Health, Physical Health and Brain Injury Services, as well as the GP Blood Test Department. When I was sent to the Blood Test department last year it was some consolation that I was being jabbed in the arm in a place of significant history.

The chapel (Grade 2 listed) was built in 1856 to serve the lunatic asylum, and still on the site although used for a different purpose

Most of the other buildings associated with the asylum have now been demolished, but nearby are the asylum’s 1856 chapel (Grade 2 listed) and the fenced-off and boarded-up remains of what I believe was “the villa,” the 1912 building for treating epilepsy (which had been treated as a mental illness up until the early 20th century). The recently restored water tower also remains.

Although it would have been great to jump into the story of the Chester Lunatic Asylum without delay, the background information was absolutely necessary to make any sense of that story. In part 1, I have tried to do provide a sufficiently detailed background to give a sense of how the Chester Lunatic Asylum fits into the full history of mental health care in the 19th century. In part 1 (split into part 1.1 and part 1.2 to make it easier to manage, but both posted on the same day) I look at the background history of what were known as lunatic asylums in the 18th and 19th centuries, with some additional brief comments on how this overlapped with workhouses. Sources and references for all parts can be found here. A version of parts 1.1 and 1.2,without images, can be downloaded as a single PDF here (27 pages of A4)

In part 2 (also split into two parts) I discuss the Chester asylum itself, built in 1829, the name of which changed many times over the period of its use as an establishment for treating mental illness. Part 2 has been written and will be posted as soon as I have added in the images, probably next week.

Many thanks to historian Mike Royden for sharing his knowledge about the Tudor and Victorian Poor Laws and workhouses. You can find out more about Mike’s research on his History Pages website.

===

18th and 19th century terminology and its limitations

From at least the 17th century the terms “madhouse” and “lunatic asylum” were terms employed to indicate a place that confined the mentally ill. These institutions were differentiated from hospitals that dealt with more conventional medical problems where attempts were made to treat rather than confine patients. The term “asylum” was originally used to refer to places of refuge, retreat and sanctuary, but up until the late-18th century the lunatic asylums were generally custodial in character, often keeping inmates in very poor conditions, and were usually referred to as mad-houses. By the 19th century an asylum was generally an establishment that made claims to treat as well as confine inmates.

From at least the 17th century the terms “madhouse” and “lunatic asylum” were terms employed to indicate a place that confined the mentally ill. These institutions were differentiated from hospitals that dealt with more conventional medical problems where attempts were made to treat rather than confine patients. The term “asylum” was originally used to refer to places of refuge, retreat and sanctuary, but up until the late-18th century the lunatic asylums were generally custodial in character, often keeping inmates in very poor conditions, and were usually referred to as mad-houses. By the 19th century an asylum was generally an establishment that made claims to treat as well as confine inmates.

Terms such as “mad” and “lunatic,” as well as “idiot” and “imbecile” are now considered to be pejorative, as well as imprecise, and are no longer used in medical, psychiatric, sociological, legal or political contexts today. In the Victorian and Edwardian periods, however, these were the standard terms used for those who suffered from some form of mental illness that incapacitated them emotionally or cognitively, temporarily or permanently, along a continuum from violent or otherwise harmful behaviour to mere learning difficulties. The term “insanity” was also in common usage, but has not been entirely excluded from modern usage. All terms are used throughout this post, reflecting the usage of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Insanity in the 18th and 19th centuries could include a vast array of conditions including delusions, paranoia, self-harm, hysteria, mood-swings, visions, speaking in tongues, irrational violence against others, senility, alcoholism, epileptic fits, dementia, mania, depression and suicidal behaviour. Even eccentricity, such as spiritualism or unconventional social behaviour, was sometimes interpreted as incipient lunacy and could lead to illicit confinement.

Excerpt from Historic England’s Glossary of Disability

The earliest owners and overseers of mad-houses were known as “mad-doctors,” a term from which 19th century asylum owners attempted to distance themselves. The later specialists in mental illness who claimed (and in some cases did) focus on treatment and cure, who were the predecessors of today’s psychologists and psychiatrists, were known as “alienists.” The term derives from the idea of mental alienation.

When the only practical solution to lunacy was incarceration, it should have been a priority to establish a set of universal definitions for the unmanageable symptoms of lunacy, but without a centralized approach to this problem, none were forthcoming. This lack of agreement about what did and did not constitute madness is exemplified by the case of Mrs Catherine Cumming who was abducted from her home and taken to York House Asylum near Battersea in London. After a period of incarceration and a long legal battle, she was declared sane by a jury, and released. When Thomas Wilmot, who had signed her lunacy certificate, was asked what he thought lunacy was, he replied that he had never seen a reasonable definition. One of the most notable features of the Cumming case was the number of medical experts called as witnesses, nineteen of them, including such notable names as John Conolly, Sir Alexander Morison and Dr Edward Monro. As Sarah Wise summarized:

After the Cumming case, it was once again noted by most commentators how unsatisfactory it was that nineteen eminent medical men could give widely differing opinions of what constituted soundness of mind, tailoring their learning according to what ‘side’ in the dispute had hired them. One alienist had claimed that Mrs Cumming was a monomaniac, another that she was an imbecile, and yet another that she was perfectly sane. . . How safe was anyone when the experts had such divergent views of insanity? [Inconvenient People, p.177]

Individual conditions now required names so that patients could be labelled, statistics logged and cases discussed. For example, research by Hill and Laughurne, based on 1870s records from St Lawrence’s Asylum in Bodmin (Cornwall), identified the most common conditions suffered by those admitted at the asylum. Although the main reasons for admission were recorded as mania, dementia, melancholia, moral insanity and the combination of manic behaviour and dementia, it is not at all clear what these terms represent. Hill and Laughurn tentatively apply the following attempts to suggest modern equivalents: mania probably representing overactive episodes; dementia, which appeared to include loss of cognition, memory loss, intellectual deficit, schizophrenia and losses of concentration; melancholia, which seems to have mainly indicated underactive episodes relating to depression; moral insanity (unspecified) and the combination of manic behaviour and dementia, which possibly describes bipolar disorder.

Individual conditions now required names so that patients could be labelled, statistics logged and cases discussed. For example, research by Hill and Laughurne, based on 1870s records from St Lawrence’s Asylum in Bodmin (Cornwall), identified the most common conditions suffered by those admitted at the asylum. Although the main reasons for admission were recorded as mania, dementia, melancholia, moral insanity and the combination of manic behaviour and dementia, it is not at all clear what these terms represent. Hill and Laughurn tentatively apply the following attempts to suggest modern equivalents: mania probably representing overactive episodes; dementia, which appeared to include loss of cognition, memory loss, intellectual deficit, schizophrenia and losses of concentration; melancholia, which seems to have mainly indicated underactive episodes relating to depression; moral insanity (unspecified) and the combination of manic behaviour and dementia, which possibly describes bipolar disorder.

Similarly, a table from the 1855 report for the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum, for both males (M) and females (F), shown below, records that the overarching symptoms in that year were mania, melancholia, dementia and amentia (defined as idiocy and imbecility), and these were further sub-categorized by the presence of epilepsy, general paralysis (also known as general paresis), and suicidal propensity.

The “Committee of Visitors and Superintendent of the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum Report” of 1855, showing Reasons for Admission. Wellcome Collection

Unfortunately, the terms for mental illnesses are not used consistently from one institution to another, meaning that mapping them on to modern conditions can be very difficult. The term dementia, for example, covered a variety of symptoms relating to mental illness at St Lawrence’s and Chester, but has become rather more precisely defined today. Epilepsy was subsumed into the general category of mental illness until the later 19th and early 20th century when special epilepsy treatment centres were introduced, intended to be more domestic and less institutional. Suicidal behaviour, with the multiplicity of potential causes and symptoms, even now sits in a somewhat liminal area between mental illness and the ability to make coherent decisions, blurring boundaries.

Admissions, Discharges (Cured and Relieved) and Deaths for Cheshire County Asylum, 1860. Source: Wellcome Collection

Another of the many challenges to understanding how lunatics were assessed was that there were no criteria for how a successful cure could be identified. In York the Tuke’s compassionate asylum The Retreat, it was assumed that anyone who had been released was cured if they were not readmitted, but not only could this represent wishful thinking without additional data, but it sidestepped the task of creating behavioural or other measures that might be used in asylums to determine whether or not someone ought to be released or detained. Like other asylums, the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum annual records show that each year a number of patients were released from the asylum, but it is impossible to know what this actually means, as there are no recorded criteria for determining whether or not a patient had been cured or, for example, sent home because they were not necessarily cured but were not dangerous to themselves or others (usually referred to as “relieved” rather than cured). The failure to define criteria to measure the success of treatment and recovery was a serious problem once patients were certified insane and committed to an asylum, because there was no universal agreement about how recovery could or should be recognized. As well as being imprecise, the lack of clear definitions and criteria was potentially an invitation to corrupt or merely sceptical asylum owners to hold patients indefinitely.

For more on these and other terms see Historic England’s Glossary of Disability History.

===

Practical problems associated with early mental illness

Engraving by T. Bowles 1735. “In a lunatic asylum, and in the company of a variety of other deranged individuals, a half-naked Ramble Gripe, his wrists chained, is restrained by orderlies.” Wellcome Collection Reference 38347i

Depending on its severity many forms of mental illness, and conditions like epilepsy that were interpreted as occasional bouts of madness, could be intensely distressing for the families and friends concerned. Not only were the symptoms apparently incomprehensible and might seem to be completely random, but they contravened social norms and conventions in a society that placed great value on normative behaviour. It might be very difficult to manage the situation if symptoms were particularly acute, requiring physical intervention. Mental illness drew unwanted attention, could attract derision and social stigma, and might prevent family members from marrying due to fears of hereditary contamination. Depictions of insanity in drama, literature, art, newspapers and magazines only inflated stigma and misunderstanding. Unfortunately, until the 18th century there was very little official support for mental illness. In rural locations families who could not keep a mentally or otherwise disabled family member at home could pay for their mentally ill relatives, including those with learning difficulties, to be cared by villagers or at local farms in need of income, sometimes providing indigent widows with a means of generating income. There was no official record of mentally ill people cared for at home.

Wealthy families could either hire an appropriate person to join the household to care for the afflicted individual, or send them to a private home or a privately run asylum where a frequently unqualified person would charge a fee to take the problem off a family’s hands. Families with middle class and reliable working class incomes might depend on any home-based family members, usually female, to provide care, but less expensive privately run houses might again provide a solution. Private mad-houses only began to become prevalent from the 17th century, and operated as lucrative businesses, unlicensed, unregulated and without oversight, there were mad-houses priced for most pockets. They were often owned or managed by individuals with no qualifications and run without any medically qualified person in attendance. Even when operated by physicians or surgeons, these titles covered a multitude of sins and might mean anything from someone who was genuinely attempting to treat ailments to a quack doctor who was little better than a profiteering snake-oil salesman.

At the main gates to Bethlem at Moorgate were two sculptures, which just about say it all: “Melancholia” and “Raving Madness” (in chains) in 1689 by Caius Gabriel Cibber. Source: Wellcome Institute via Wikipedia

For pauper families, a lunatic family member was an even greater burden. Lunatics whose families could not support them were forced to resort to begging. These were amongst the most isolated and vulnerable people in society. The pauper insane were undifferentiated from other paupers, including vagrants, tramps, beggars. Many found themselves in workhouses, and workhouses continued to have a role housing those will mental illnesses well into the 19th century. Other less fortunate pauper lunatics would be incarcerated in prisons, particularly when violent.

The first charitable mad-house was the 1247 Priory of Our Lady of Bethlehem in London, which had taken in the insane from the early 15th century as a monastic duty. For most of its life it was a small institution, with a capacity of few more than 40 individuals, but by the mid 19th century it was suffering from overcrowding. Following the Great Fire of London in 1666 the largest public asylum investment in dealing with lunacy was the 17th century was in the new Bethlehem (also known as Bethlem and Bedlam), which opened in Moorfields on the edge of London in 1676 for 120 patients, with additional extensions added as it reached capacity. Conditions were notoriously dire until the early 19th century.

Outside London care was organized under local parishes in a highly decentralized way, and these would sometimes provide accommodation for those who, through no fault of their own, were unable to support themselves. Charitable asylums began to appear throughout England in the early 18th century, first in Norwich and London, then in Newcastle and Manchester by the middle of the century and, towards the end of the 18th century, others in York, Leicester, Liverpool and Hereford.

===

Perceptions of lunacy in society in fiction and theatre

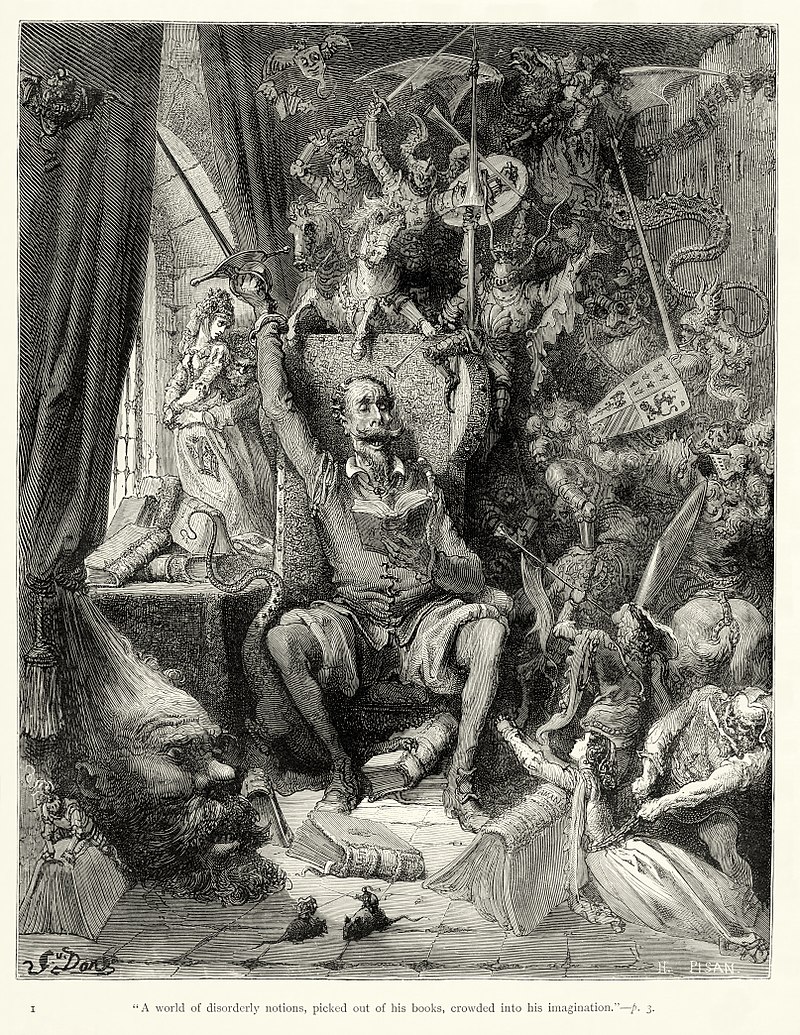

Gustave Doré illustration of Don Quixote in 1863. Source: Wikipedia

Accounts of madness appear in both Old and New Testaments, where they often provided a moral allegorical aspect to religious narratives. As literacy and theatre became increasingly popular, insanity became a major literary device in drama and poetry from the Elizabethan period. This helped to spread an idea of insanity that was something both alien and dark, but at the same time eerily recognizable in the real world, creating both curiosity and fear. The dramatization of madness appealed to the same sense of fascination, aversion and suspense that horror and science fiction genres generate today.

Many playwrights used madness to add dramatic emphasis to a number of their plays including Christopher Marlowe’s Dr Faustus (first performed c.1594), Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (first performed 1587), Shakespeare’s Hamlet (first performed c.1601), King Lear (c.1606), and Macbeth (first performed c.1611), Webster’s Duchess of Malfi (first performed 1614) and John Fletcher’s The Pilgrim (first performed 1621). The novel Don Quixote (c.1605) by Miguel Cervantes, which depicted outright insanity as the main subject matter, was first translated into English in 1612, with a more popular version in 1700. In the 18th century Tobias Smollett also translated Cervantes but also offered his own treatment of madness in Sir Launcelot Greaves (1760). Samuel Richardson explored his own versions of female madness in Clarissa (1748) and Sir Charles Grandison (1753). In the late 18th and early 19th century George Crabbe’s poetry makes frequent reference to madness, and his poem Sir Eustace Grey (published in his collection of 1807), set in a “mad-house” and framed as a conversation between a patient, a doctor and a physician, examines the decline of a sane person into insanity.

The more he felt misfortune’s blow;

Disgrace and grief he could not hide,

And poverty had laid him low:

Thus shame and sorrow working slow,

At length this humble spirit gave;

Madness on these began to grow,

And bound him to his fiends a slave.

Engravings of a series of William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress paintings, published in 1735, include this scene from a lunatic asylum, with wealthy female visitors looking on. Source: Wikipedia

Visual depictions are dominated by William Hogarth’s famous Rake’s Progress, which included a scene showing the Bethlem the asylum as a deranged and frenzied environment viewed by two wealthy ladies visiting the asylum to enjoy a spectacle of curiosity. Although painted in the early 1730s it was engraved in 1755 after which it was widely distributed. Satirical cartoonists, building on the work of Hogarth, became very popular in the 18th century, of whom James Gillray is by far the best known, although there were many others. The satirical publication Punch shared many of these, and it was by no means unusual for them to depict politicians and other senior figures as madmen, some of them chained up in lunatic asylums, showing slapstick, scatological and often puerile visions of a flawed society. As Cartoonist Martin Rowson says:

Bethlem Hospital, London: the incurables being inspected by a member of the medical staff, with the patients represented by political figures. By Thomas Rowlandson 1789. Source: Wellcome Collection Ref 536228i

Personally, I believe satire is a survival mechanism to stop us all going mad at the horror and injustice of it all by inducing us to laugh instead of weep. . . That’s why, if we can, we laugh at both those things, as well as being disgusted and terrified by them. Beneath the veil of humour, there’s always a deep, disturbing darkness. [The Guardian, March 2015]

References to behaviour that seemed ill-suited to the rational world, particularly amongst politicians and the social elite, were easily ridiculed by reference to lunatic asylums, which played on the fears of society as well as on its inclination to deride the sane.

The Woman In White by Wilkie Collins, first serialized in 1859 before being published as a book. Source: Wilkie Collins Information Pages

Madness was a recurring theme in 19th century literature and British Victorian fictional literature continued to offer insights into how society perceived lunacy. Works include Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847); The Woman in White (1859) and the short story Fatal Future (1874) both by Wilkie Collins; Charles Reade’s Hard Cash (1863); Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886), and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), to name but a few. Insanity also finds its way into many novels and stories by Charles Dickens including the short story A Madman’s Manuscript (1836, from The Pickwick Papers) and the novels Bleak House (early 1850s) and Great Expectations (1861).

Madness was also featured in opera, particularly adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays, and those by Gaetano Donizetti who made particular use of madness as a device. Donizetti’s Anna Bolena of 1830, in which Anna (Anne Boleyn) goes mad in the Tower of London as she awaits execution, suffering delusions) was premiered in London 1831. Donizetti’s 1838 Lucia de Lammermoor, based on Sir Walter Scott’s 1819 novel The Bride of Lammermoor, in which the eponymous heroine goes mad when her brother forces her into a loveless marriage, was first performed in London in 1836, with a famous Eccola! mad scene. Lucrezia Borgia, dates to 1833 and was premiered in London in 1839. Other well known operas that feature insanity are Vincenzo Bellini’s I Puritani, in which the heroine goes mad when she is abandoned at the altar and in Wolgang Amadeus Mozart’s Idomeneo win which the vengeful Elettra, another woman unlucky in love, goes splendidly mad with grief and rage at the end of the opera.

The mad Bertha Mason as envisaged by F. H. Townsend for the second edition of Jane Eyre, published in 1847. Source: Wikipedia

The above-mentioned functional works by Charlotte Brontë, Wilkie Collins and Charles Reade dealt with wrongful detainment, either at home or in an asylum, bringing a new risk to public attention. The impact of these fictional works were considerably exacerbated by real-life incidents of wrongful detainment. Sarah Wise’s book Inconvenient People provides many examples of illicit incarceration and how these were handled. An early 19th century example is the case of one Mrs Hawley. It is worth quoting James Peller Malcolm’s 1808 account in Anecdotes of the Manners and Customs of London during the Eighteenth Century Including the Charities, Depravities, Dresses, and Amusements etc to give an example of how the sort of accounts that the public were reading:

Amongst the malpractices of the Century may be included the Private Mad-houses. At first view such receptacles appear useful, and in many respects preferable to Public; but the avarice of the keepers, who were under no other control than their own consciences, led them to assist in the most nefarious plans for confining sane persons, whose relations or guardians, impelled by the same motive, or private vengeance, sometimes forgot all the restraints of nature, and immured them in the horrors of a prison, under a charge of insanity. Turlington kept a private Mad-house at Chelsea: to this place Mrs. Hawley was conveyed by her mother and husband, September 5, 1762, under pretense of their going on a party of pleasure to Turnham-Green. She was rescued from the coercion of this man by a writ of Habeas corpus, obtained by Mr. La Fortune, to whom the lady was denied by Turlington and Dr. Riddle; but the latter having been fortunate enough to see her at a window, her release was accomplished. It was fully proved upon examination, that no medicines were offered to Mrs. Hawley, and that she was perfectly sane.

This incident lead to a Select Committee investigation appointed by the House of Commons to investigate wrongful detention in private asylums, and lead to Madhouse Act of 1774 (on which more later), which recognized the problem and although it did not do nearly enough to tackle it, set a useful precedent for applying legal measures to madhouses. Legislation throughout the 19th century attempted to prevent wrongful certification, but there were four highly publicized scandals on illegal incarceration in 1858 that fuelled public fear and even as late as 1890 laws were being introduced to prevent collusion between those attempting to admit sane patients and certain medical men incentivized to receive them.

Introduction to Nellie Bly’s account of her undercover work in an American asylum. Source: Internet Archive

The requirements for committing the poor in public asylums were less stringent. This was not an elitist measure. The wealthy were far more vulnerable to family manipulation for self-gain, and as Sarah Wise has demonstrated, men were just as vulnerable in this respect as women. Pauper lunatics whose families had little financial incentive to incarcerate impoverished relatives, except to reduce the pressure on household costs. On the other hand the wealthy were universally treated far more kindly than the poor.

In America, Nellie Bly’s late 19th century journalistic account of the ten days she spent on an undercover assignment, incarcerated in an American women’s asylum caused a public outcry similar to that attached to the repeated scandals at Bethlem, the York Lunatic Asylum scandals in 1790 and 1814 and the four highly publicized cases of 1858. Bly’s experiences were published and widely distributed in book form in 1887. Nellie Bly, the pen-name for Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, was a correspondent on The New York World, and her articles and book served to raise awareness of the true horrors that still existed so late in the 19th century on both sides of the Atlantic.

All these different types of medium demonstrate that madness was a powerful artistic and dramatic device, eliciting feelings of both fascination and dread.

===

Approaches to lunacy before 1830

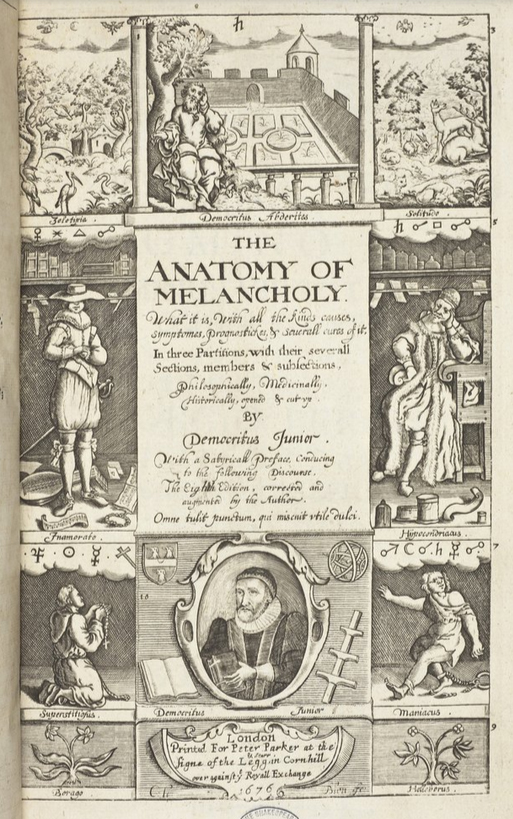

The 1676 front page from “The Anatomy of Melancholy” by Robert Burton, first published in 1621. Source: Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

One of the earliest non-fiction books to be published on the subject of mental instability was Robert Burton’s (1577 – 1640) startling and difficult 1621 The Anatomy of Melancholy which ranges freely through all aspects of religion, the Classics and literature to discuss, in a somewhat tangled narrative, a variety of behaviours that he brings together under “melancholy” that he generally equates to madness:

That men are so misaffected, melancholy, mad, giddy-headed, hear the testimony of Solomon, Eccl.ii.12. “And I turned to behold wisdom, madness and folly,” &c. And ver.23: “All his days are sorrow, his travel grief, and his heart taketh no rest in the night.” So that take melancholy in what sense you will, properly or improperly, in disposition or habit, for pleasure or for pain, dotage, discontent, fear, sorrow, madness, for part, or all, truly, or metaphorically, ’tis all one. Laughter itself is madness according to Solomon, and as St. Paul hath it, “Worldly sorrow brings death.” “The hearts of the sons of men are evil, and madness is in their hearts while they live,” Eccl.ix.3. “Wise men themselves are no better.” Eccl.i.18.

This is one of many publications that demonstrate that there was no science-based medical understanding of madness before the later 19th century, partly because there was little understanding of human anatomy or neurology, and partly because of the existence of well-honed model of human biology. In the late 11th century the published research of Arab scholars came to the west, where it had a colossal impact on how the world was understood and interpreted, offering new explanatory models that were not dependent on Christian conventions or traditional folklore, but were still woefully inaccurate.

The Four Humours and their characteristics. Source: National Library of Medicine

The dominant medical model from the medieval period, echoes of which lasted well into the 19th century, derived from Greek thinking was medical, based on Hippocrates and modifications of Hippocrates by Galen. Forming the foundation of medieval ideas of biology and the treatment of ailments, these beliefs were based on the theory that humans were were made up of four basic elements called humours, which were characterized by specific properties that had to be kept in balance in order for health and well-being to be maintained. Failure to balance these humours was thought to result in illness and/or mental instability. This was a powerful explanatory model that appeared to offer solutions but although it avoided some often unpleasant divine, magical and superstitions approaches, with which it lived side by side, it represented a complete lack of understanding of human biology and anatomy. Various often painful and harmful techniques were employed in attempts to restore equilibrium to these imaginary humours. Some of the treatments were quite literally torturous, intended to draw out or counteract imbalances. Together with explanations citing demonic influence, the humours were an important part of medieval belief that leaked into the 18th and early 19th centuries. Treatments included restraints long periods of isolation and so-called treatments including purging, bloodletting, food deprivation, hot and cold water immersion and beating to attempt to treat madness with physical measures, and presumably to enforce better behaviour.

The issue of whether or not madness could be treated to reduce or eliminate symptoms became a matter of considerable importance to the royal family and the government at the end of the 18th century. Beginning in the 1780s, King George III (1738-1820) experienced phases of severe mental disturbance. This brought with it an interest in research into symptoms of madness at state level. The king’s medical team included Francis Willis, a former clergyman who owned an asylum in Lincolnshire. Willis’s treatment of King George indicates that the treatments employed in both private and public asylums were genuinely believed to have a beneficial impact because the king was subjected to the same type of treatment practised to rebalance humours, and which Willis used in his own asylum, including ice baths, purging, enforced vomiting, burns, denial of food, and restraints. King George appeared to improve after treatment, and Willis was well-rewarded, but the king’s condition worsened again in the early 18900s. In 1810, perhaps because his illness was exacerbated by the death of his daughter Princess Amelia, he withdrew from official duties, although lived for another 10 years.

The issue of whether or not madness could be treated to reduce or eliminate symptoms became a matter of considerable importance to the royal family and the government at the end of the 18th century. Beginning in the 1780s, King George III (1738-1820) experienced phases of severe mental disturbance. This brought with it an interest in research into symptoms of madness at state level. The king’s medical team included Francis Willis, a former clergyman who owned an asylum in Lincolnshire. Willis’s treatment of King George indicates that the treatments employed in both private and public asylums were genuinely believed to have a beneficial impact because the king was subjected to the same type of treatment practised to rebalance humours, and which Willis used in his own asylum, including ice baths, purging, enforced vomiting, burns, denial of food, and restraints. King George appeared to improve after treatment, and Willis was well-rewarded, but the king’s condition worsened again in the early 18900s. In 1810, perhaps because his illness was exacerbated by the death of his daughter Princess Amelia, he withdrew from official duties, although lived for another 10 years.

By far the most common solution for non-royal lunatics was some form of containment. As Lucy Series puts it: “A key tenet of the law of institutions is that some people belong in ‘institutions’ (at least some of the time) and others do not.” Those institutions were designed to separate the mad from their homes and communities “spatially, legally and socially.” It was from the late 17th century in London and the 18th century elsewhere in Britain that the problems associated with madness began to be approached by both private enterprise and, more slowly, charities. Private asylums were unlicensed and unregulated, operating completely outside any legal framework, and as early as 1728 Daniel Defoe (writing under the pseudonym Andrew Moreton) referred to the “vile practice” of incarcerating family members for personal advantage. Operated as commercial ventures, and often very profitable, they grew in great numbers. The new 1676 public Bethlem hospital for 120 patients, was designed by Robert Hooke along impressively grandiose lines but it was poorly constructed and deteriorated rapidly, requiring extensive maintenance and repair. It has become infamous for charging tourists a fee to view the mentally disturbed, a practice not stopped until 1770. It treated the mentally ill as sub-human, barely better than chained animals, and conditions became notoriously dreadful, not tackled until a new reformist superintendent was installed in 1815.

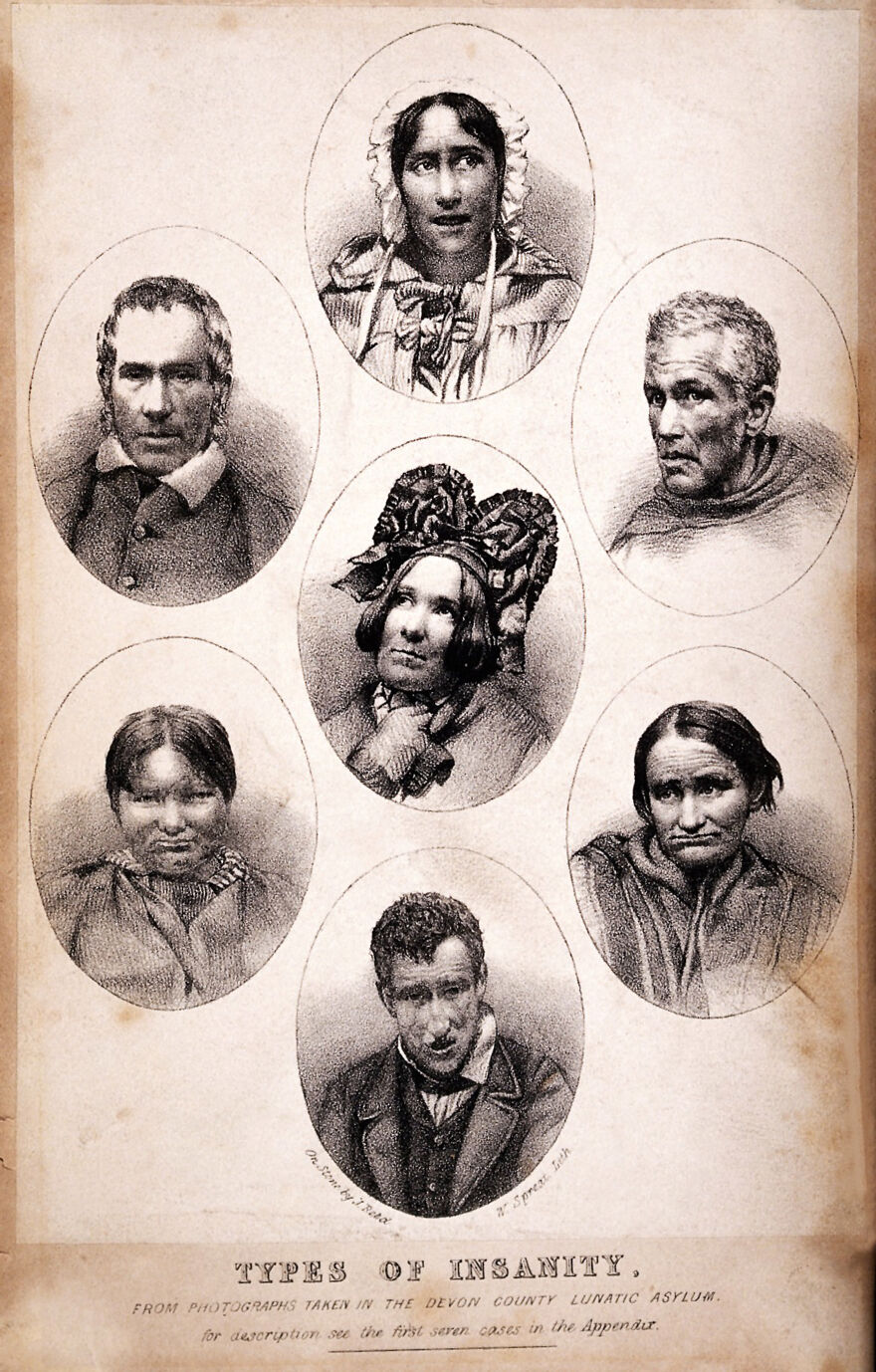

Seven vignettes of people suffering from different types of mental illness. Lithograph by W. Spread and J. Reed, 1858. Source: Wellcome Collection, Ref. 20076i

As the 19th century proceeded, lunacy or madness was interpreted in different ways, both medical and philosophical, drawing together the brain, the body and the mind in new exploratory but untested directions. In Britain, as well as elsewhere, physical examination of the skull (phrenology) and the face (physiognomy) were approaches that attempted to find the source of madness in visible physical details, but there was little attempt to develop a scientific understanding of madness or how to treat it. Britain’s alienist German counterparts, were more closely affiliated with universities and adopted academic approaches, and developed new ideas towards mental illness in laboratory environments where hypotheses formed and tested. It is in Germany that the term “psychiatry” was first coined in the early 19th century, and from where many of the innovations in understanding mental illness started to emerge. In the late 19th century Emil Kraepelin, Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Heidelberg, recognized and described the mental illness dementia praecox, later renamed schizophrenia. This type of research began to influence some British researchers, some of whose own work was recorded in the Journal of Mental Science. Linkages between pathological conditions (such as infectious disease), and mental conditions were only recognized in the later 19th century. For example, the connection between the sexually transmitted infection syphilis and its late-phase symptoms (including mood swings, antisocial behaviour, delusions and seizures) was only recognized in the late 1880s.

There were no medicines available to treat the causes of mental illness. The only medications available were for the treatment of symptoms, not causes. Tranquilizers, a certain amount of pain relief and the treatments for fever were the only available forms of relief for patients. For very violent patients the only measures were sedatives, restraints and isolation.

===

The growth of the lunatic asylum 1751-1834

Sketch of the original plan of the Chester Union Workhouse. Source: Chester – A Virtual Stroll Around the Walls

The Old Poor Law (officially the Act for the Relief of the Poor) of 1601 had been instigated during the reign of Elizabeth I was modified but largely changed until the 1834. It classified paupers as the able-bodied who were unable to find employment, the able-bodied who refused to find employment, and those who due to illness, old age, disability or other infirmities, including lunacy, were unfit for employment and needed relief. In the 18th century the institutional mechanisms available for the mentally ill who had no family assistance were mainly hospitals, workhouses, almshouses, and prisons each set up to cater for different types of problem and accompanying symptoms. Some parishes paid for lunatics to be housed in private house, where they could be confined, but public funding of lunatic confinement was unusual.

The problem of poverty and paupers is well represented by the multitude of poor laws that were introduced throughout the Tudor and Jacobean periods. The church and charitable organizations might assist with payments and household supplies, and even housing for the poor, providing a accommodation and food in return for labour, but such resources were few and far between and did not apply to lunatics. A much more familiar solution for the pauper insane became the workhouse, an early institution initially set up with the laudable intention of helping the poor on a parish by parish basis, partly funded by the “poor rate”, and which also took in the pauper insane. Charitable public lunatic asylums, some raised by subscription, were introduced at the end of the 18th century, and became more important as workhouses became more penal in character, but workhouses were still acknowledged places of detention and safekeeping for the insane and the imbecile well into the 19th century.

The 1713 and 1744 Vagrancy Acts distinguished between lunatics and criminals, imposing much less severe treatment on the former, but providing for their detention. In practice, this meant incarceration in a jail or Bridewell rather than a death sentence. In 1723 the General Workhouse Act, intending to reduce the ongoing costs of maintenance of unemployed paupers, allowed parishes to erect a workhouse, and judge whether those who were out of work should be sent to the workhouse and to labour for their shelter and food. They were built all over Britain in their 100s. Paupers with learning difficulties or mental illnesses were regularly subsumed into the workhouse system due to the lack of any practical alternative. Although anyone could leave, at least in theory, the workhouse was not a place of rehabilitation, and was designed to be sufficiently ghastly to deter people from seeking state help. Some workhouses had a wing for lunatics, but the conditions were very poor. Whilst it probably did lead some to seek work, the system penalized those who were genuinely unable to work.

St Luke’s Hospital, Cripplegate, London: the facade from the east. Engraving after T. H. Shepherd. Source: Wellcome Collection, ref. 26120i

A new model of lunatic asylums is represented by St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics, founded on Old Street in Cripplegate (London), which opened in 1751. The neoclassical façade favoured by was emulated by several later institutions. Its first head physician was Dr William Battie, who set himself up in opposition to the barbaric and punitive regime at Bethlem, and published his Treatise on Madness in 1758, describing his contrasting approach. He distinguished between un-treatable congenital madness and that caused by a social environment, which might be treated. He was unusual in preferring treatment to constraint, and although his methods were interventionist, his belief that mental illness was treatable and even curable was influential. He ran a school at the hospital in the hope that this would disperse his teachings and approaches. Although he took in pauper lunatics, Battie ran the hospital as a profitable commercial venture.

The 1774 Act for Regulating Private Madhouses (and sometimes referred to as the Lunacy Act or the Madhouse Act ) was an early attempt to regulate and manage private madhouses. Public asylums were not regulated by this Act. One of its achievements was the appointment of five Commissioners who were Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians who would inspect private asylums, and although these were only in the London area it was a step towards certification and licencing. Another important measure was designed to ensure that anyone committed required two referrals by qualified doctors to ensure that individuals were not wrongfully confined by their families.

In 1782 The Act for the Relief and Employment of the Poor (also known as Gilbert’s Act) allowed parishes to form themselves into groups for the purpose of building workhouses exclusively for those unable to work. No able-bodied people were to be admitted. Although this was not a successful measure, being entirely optional with a poor take-up, it did acknowledge a real need for providing for the physically and mentally infirm.

As William Battie had demonstrated, real change lay as much in philosophical, ideological and humanitarian ideas as medical and legal ones. The Quaker movement had a strong influence on this idealized way of treating mental illness, and this grew partly out of the death of Quaker Hannah Mills in 1790, less then a month after being admitted to the York Lunatic Asylum (opened 1777), suffering from melancholy. She was one of some 300 inmates who died there in the 37 years between 1777 and 1814. Her case came to the attention of the Quaker and wholesale tea trader William Tuke (1732-1822). Horrified by the facts of the matter, decided to raise funds to build an asylum in which members of the Quaker community suffering from mental health problems could be treated in a new and civilized way. The result was his own asylum called The Retreat, which opened in 1792. His approach, referred to as the “moral” treatment, was altogether more compassionate and empathetic, based on the belief that a positive physical and emotional environment and good food were key to mental recovery. A nurturing and therapeutic approach to care was adopted. Instead of being treated as sub-human or bestial, those who entered the asylum were encouraged to lead lives emulating social norms. Restraint was only used when strictly necessary, and although patients were confined within an institution, the Retreat attempted to reproduced ordinary home living and encouraged socializing amongst patients to help patients to recover. William Tuke’s son also worked at the asylum, and his grandson Samuel Tuke (1784-1847), published a description of The Retreat in 1813, describing the philosophy and activities of the asylum. This publication helped to inform other mental illness reformers.

As William Battie had demonstrated, real change lay as much in philosophical, ideological and humanitarian ideas as medical and legal ones. The Quaker movement had a strong influence on this idealized way of treating mental illness, and this grew partly out of the death of Quaker Hannah Mills in 1790, less then a month after being admitted to the York Lunatic Asylum (opened 1777), suffering from melancholy. She was one of some 300 inmates who died there in the 37 years between 1777 and 1814. Her case came to the attention of the Quaker and wholesale tea trader William Tuke (1732-1822). Horrified by the facts of the matter, decided to raise funds to build an asylum in which members of the Quaker community suffering from mental health problems could be treated in a new and civilized way. The result was his own asylum called The Retreat, which opened in 1792. His approach, referred to as the “moral” treatment, was altogether more compassionate and empathetic, based on the belief that a positive physical and emotional environment and good food were key to mental recovery. A nurturing and therapeutic approach to care was adopted. Instead of being treated as sub-human or bestial, those who entered the asylum were encouraged to lead lives emulating social norms. Restraint was only used when strictly necessary, and although patients were confined within an institution, the Retreat attempted to reproduced ordinary home living and encouraged socializing amongst patients to help patients to recover. William Tuke’s son also worked at the asylum, and his grandson Samuel Tuke (1784-1847), published a description of The Retreat in 1813, describing the philosophy and activities of the asylum. This publication helped to inform other mental illness reformers.

Depiction of “The Retreat,” established by William Tuke in 1792, by George Isaac Sidebottom, a patient at the retreat in the late 19th century. Source: Wellcome Collection RET/2/1/7/5

Following the 1808 County Asylum’s Act known as “Wynn’s Act” after Charles Williams-Wynn, the politician who did much to promote it, Justices of the Peace were given the authority to build county asylums, and to raise finance to do so. This was optional, not compulsory, and local councils were under no obligation to build asylums. Although some new asylums were subsequently built to enable paupers with mental illnesses to be removed from workhouses and placed in appropriate establishments these were slow to arrive. Many who suffered with mental illnesses or learning difficulties continued to be taken into workhouses and prisons. The treatment of the poor continued to be a story of failure to respond to a serious need, whilst the rich were still regularly deposited in private institutions of very variable quality.

York Lunatic Asylum. Source: Wikipedia

In the meantime, the York Lunatic Asylum, first under physician Alexander Hunter, and after his death in 1809 under his assistant Dr Charles Best, continued to take a custodial, punitive and disgustingly neglectful approach to its patients, a fact that Tuke and other York philanthropists attempted to address, partly by reporting cases to the media and partly by infiltrating the board of governors and using this to demand access to the asylum to inspect patient care, finding that although wealthy patients were usually well treated, pauper lunatics were kept in dreadful conditions. Godfrey Higgins, one of a number of social agitators in York at the time, who had taken a particular interest in the treatment of the insane, used his influence to demand an inspection in March 1814. When he found locked doors he insisted that they be opened, threatening to break them down himself. Inside one room he found female patients in what he referred to as “a number of secret cells in a state of filth, horrible beyond description . . . the most miserable objects I ever beheld.” In another part of the asylum he found “more than 100 poor creatures shut up together, unattended and unsuspected by anyone”. The case went to court, and a new committee was appointed in 1814, but problems continued to be reported.

Bethlehem (Bethlem) Hospital by William Henry Toms for William Maitland’s History of London, published 1739. Source: Wikipedia

The dire conditions at Bethlem in Moorfields continued to be a disgrace to London. Even though a decision had been made to replace the Moorfields building with a new one, south of the Thames at Southwark, matters might have gone on as before if not for Edward Wakefield, a Quaker, like the Tukes, an advocate of lunacy reform whose mother had been confined in an asylum. He had visited the Moorfields site in 1814 and reported on the inhuman conditions that he witnessed there. Wakefield’s insights were an important part of the Select Committee investigation of 1815, which reported on the appalling conditions that Wakefield had found.

A sample of Wakefield’s contribution to the 305-page report is as follows, which is by no means the most distressing: In the early 1800s it was determined that the Bethlem Lunatic Asylum building in London was no longer fit for purpose, and it was demolished, replaced by a new building in Southwark (which today houses the Imperial War Museum).

American sailor James (sometimes called William) Norris as found in Bethlem in 1815, where he had been detailed for over a decade. Source: Wikipedia

We first proceeded to visit the women’s galleries: one of the side rooms contained about ten patients, each chained by one arm or leg to the wall; the chain allowing them merely to stand up by the bench or form fixed to the wall, or to sit down on it. The nakedness of each patient was covered by a blanket-gown only; the blanket-gown is a blanket formed something like a dressing-gown, with nothing to fasten it with in front; this constitutes the whole covering; the feet even were naked. One female in this side room, thus chained, was an object remarkably striking; She mentioned her maiden and married names, and stated that she had !been a teacher of languages; the keepers described her as a very accomplished lady, mistress of many languages, and corroborated her account of herself. The Committee can hardly imagine a human being in a more degraded and brutalizing situation than that in which I found this female, who held a coherent conversation with us, and was of course fully sensible of the mental and bodily condition of those wretched

beings, who, equally without clothing, were closely chained to the same wall with herself

. . . .

In the men’s wing in the side room, six patients were chained close to the wall, five handcuffed; and one locked to the wall by the right arm as well as by the right leg; he was very noisy; all were naked, except as to the blanket-gown or a small rug on the shoulders, and without shoes; one complained much of the coldness of his feet; one of us felt them, they were very cold. The patients in this room, except the noisy one, and the poor lad with cold feet, who was lucid when we saw him, were dreadful idiots ; their nakedness and their mode of confinement, gave this room the complete appearance of a dog-kennel.

[First report from the Committee on the State of Madhouses, 1815, p.46]

The new Bethlem of 1815. Source: BBC Culture

===

Wakefield himself was appointed as the new superintendent of the new Bethlem in Southwark and he introduced similar values as those employed by the Tukes at The Retreat. The new Bethlem opened in 1815 with a wing for the criminally insane, the same year as the Select Committee report on the condition of lunatic asylums.

======

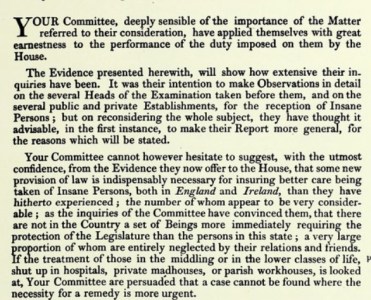

Excerpt from Committee Appointed to Consider of Provision Being Made for the Better Regulation of Madhouses in England, Parliament, House of Commons 1815-16. First report from the Committee on the State of Madhouses. London. Source: Wellcome Collection

The 1815 First report from the Committee on the State of Madhouses of the House of Commons Select Committees highlighted the lack of oversight of lunatics, and the dismal conditions in which patients that pertained in far too many asylums, workhouses and other institutions where lunatics and imbeciles were confined.

The report’s findings are elegantly phrased, but make it abundantly clear that asylums, amongst them some of the most successful institutions of the day violated basic human rights. The conditions for paupers and even those of better social standing who lacked visitors to make complaints were frequently filthy places of restraint, beatings and both physical and mental cruelty, with overcrowding, freezing cold conditions, lack of sufficient attendants, and poor admission procedures. Some of the accounts make for really harrowing reading. The most truly depressing aspect of the report is that although the committee had made heartfelt recommendations for improvements, matters remained largely unchanged because these did not pass into law.

A page from Mitford’s “Crimes and Horrors in the Interior of Warburton’s Private Mad-House at Hoxton.” Source: Internet Archive

Unsurprisingly, matters had not much improved seven years later in 1822 when John Mitford published his eye-opening A Description of the Crimes and Horrors in the Interior of Warburton’s Private Madhouse at Hoxton. Mitford’s assessment of Mr Warburton, unqualified and cruel, concludes that “[on] a careful exposure of this diabolical establishment, I doubt not all will agree with me in opinion, that these ‘lawless houses under the law’ should be done away with entirely, as a disgrace to human nature. The angel of death moves through them with secret and murderous strides.” As with Edward Wakefield’s earlier expose of Bethlem in 1815, it is a truly shocking read.

It took another decade before another Select Committee was appointed in 1827, partly due to a scandal concerning conditions and illegal incarceration at Warburton’s Mad-house in Hoxton, and partly due to campaigning by both social reformers M.P. Lord Anthony Ashley (as from 1851 Lord Shaftesbury), and Dorset magistrate Robert Gordon. This time the Committee’s reports were taken into account and two new acts were passed in 1828. The Act to Regulate the Care and Treatment of Insane Persons in England (also known as The Madhouse Act) appointed a new Commission in Lunacy to improve centralized control over asylums, not merely in London but throughout England and Wales in an attempt to provide consistent oversight. The Act attempted to tighten up the certification required before a person, either private or pauper, could be admitted to a lunatic asylum, and the Commission was given much greater powers to act in respect of private asylums. The admission of pauper lunatics now required certification by a Justice of the Peace as well as a physician. The County Lunatic Asylums (England) Act again encouraged counties to build asylums from ratepayer contributions, and also required that county asylums should send detailed reports on an annual basis to the Home Office. The Act was updated in 1832, again to attempt to improve the certification process and prevent illegal detainment, making false or inaccurate certification a misdemeanour.

Following the 1808 and 1828 Acts, several new county asylums had been built. Early examples were Nottingham, Bedford, Norfolk, Staffordshire, Cornwall, Gloucester and Suffolk all before 1830. It is at this point, to slot it into its chronological context, that the new Cheshire Lunatic Asylum was built, in 1829.

Please click here to go to Part 1.2, the second part of this background to the Cheshire Lunatic Asylum. The Cheshire Lunatic Asylum itself is discussed in Part 2.

===

The Tukes’ Retreat, a private asylum delivering “moral treatment” in York, which opened in 1792. Source: Wikipedia

Chester Lunatic Asylum 1831, a public asylum established for paupers, and a few private patients, which opened in 1829. Source: Wellcome Institute Library

====