Introduction

At the top of my to-do list for my short break to Shropshire in October was the Jackfield Tile Museum. I wanted to see all the Ironbridge area museums themed around the Industrial Revolution, and managed to do so, but I have a great love of tiles, and since I moved up to this area have been dying to visit the museum in the village of Jackfield, next to the river Severn. It was even better than I had expected. To get the most out of this museum, you have to really love Victorian and Edwardian design, because this is a celebration of the tiles produced during the late 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, but if you do, it is a superb experience.

The museum is beautifully thought out, very well lit, and the tiles are presented in a way that allows them to be appreciated and understood not only as designs, but as the products of specific manufacturing processes, as the result of industrial innovation and as the output of very proficient commercial drive. It is amazing what went in to making tiles and mosaics and turning them into a commercially viable product for both private homes and public buildings.

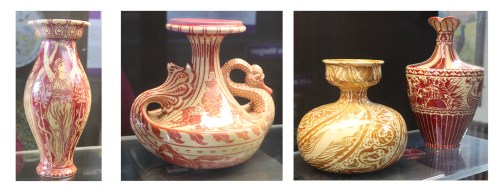

As well as original display cases and tile arrangements that show how the tiles were arranged to show to potential buyers, there are rooms showing development in artistic and craft styles (the Style Gallery) and reconstructions of entire rooms that used tiles as the major component of their decorative schemes. There are also reminders that the tile-works also made plates, vases and other decorative items. The museum also holds the John Scott Collection of tiles.

The impressively long 1872 building, the original Craven Dunnill and Co tile-works, is occupied partly by the museum and partly by a working tile-works. Today’s Craven Dunnill is a successful commercial venture building on the successes of its 19th century predecessors, a very nice link between the building’s heritage and its present manufacturing activities.

Apologies for some of the photographs. There is excellent lighting in the museum, but this sometimes makes it difficult to photograph without reflections, and many of the photographs have big patches of bright light on them. Some of the angles are a bit odd too, as I tried to lean away from the reflections. It didn’t help that I was in a bright fuchsia-pink coat, which reflected in the display cabinet glass!

Visiting details (with links to opening times, ticket prices, and parking details etc) are at the end of the post, as usual.

The length of the building reflects the way in which tiles were produced via a series of stages from east to west, from preparation of the clay to the finished product

The museum is arranged into different themed areas, which explain both different aspects of the Jackfield tile-works itself and the development in the 19th century of tiles and how they were marketed and sold, and what sort domestic, commercial and public locations they adorned.

Introductory Gallery

One of the original 19th century floors of the Craven Dunnill and Co tile-works, where prospective customers entered to view tiles in the trade showroom.

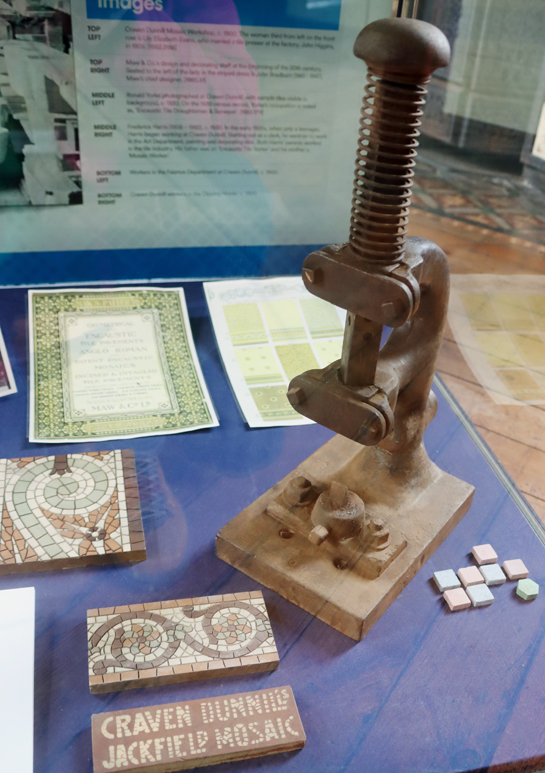

The self-guided tour starts with information boards describing the background to the tile industry and its commercial development from the 17th century, when the area was famous for its clay tobacco pipe manufacturing works at Broseley. By the 1720s there were several small potteries in Jackfield, taking advantage of locally available raw materials and the proximity of the river for power and transportation. There had been a pottery on the Craven and Dunnill site since 1728. The railway arrived in the valley in 1862, with a siding for Jackfield and stops at Coalport and Ironbridge, improving connections and the speed with which products could be shifted to market. The expansion of local industries followed, and two of the largest Victorian tile factories in the world were built next to the railway: Craven, Dunnill and Co in 1875 and Maw and Co in 1883. Tiles were valued not only for their decorative value but, in a period that was just getting to grips with the importance of hygiene, were easy to clean. By 1881 Craven Dunnill and Co had 94 workers including 53 men, 15 women and 25 youths.

The Trade Showroom

The first gallery, The Trade Showroom, is the display area of the Craven Dunnill and Co. tile-works, where architects, interior decorators and their customers could view catalogues, but could also see samples of the company’s tiles wherever they looked. Today’s layout preserves one of the company’s original display cabinets, and the tiles on the walls, including floor and wall tiles, are based on images of this room as it was in the 19th century. Display cabinets in the middle of the room show other aspects of the company’s operations. On this floor there are also reconstructions of the offices that would have existed in the building in the Victorian period, with recordings that you can listen to, capturing accounts of personal memories of the tile-works in the past.

A design book by Owen Gibbons from 1881. Gibbons and his brother taught at the Coalbrookdale School of Art, producing many tile designs

Style Gallery

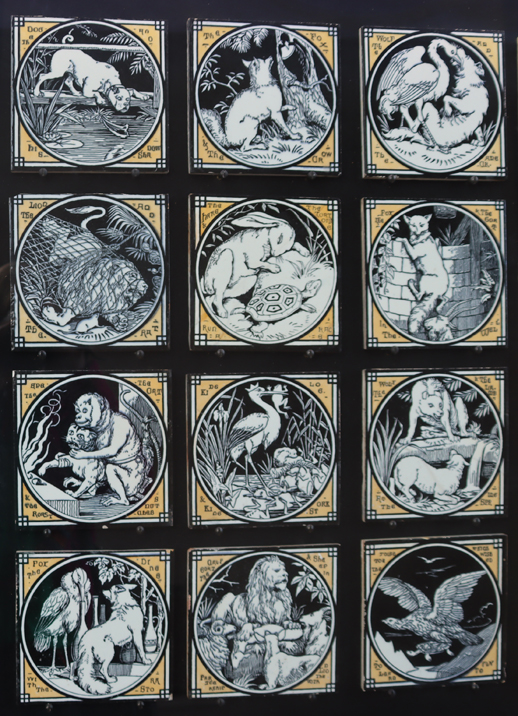

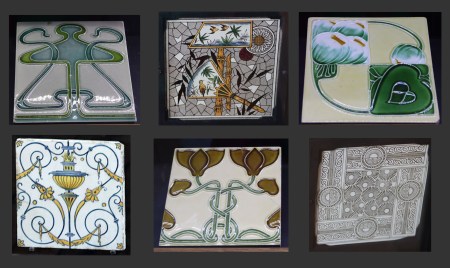

The Style Gallery offers a eye-dazzling view of the sheer number of fashions in tile design that trended during the Victorian period. It is a reflection not only of how the Victorians were interested both in referring to and interpreting the familiar past, and reinventing the present but of how some of these styles employed imagery from the Far East and and the Middle East.

The Style Gallery offers a eye-dazzling view of the sheer number of fashions in tile design that trended during the Victorian period. It is a reflection not only of how the Victorians were interested both in referring to and interpreting the familiar past, and reinventing the present but of how some of these styles employed imagery from the Far East and and the Middle East.

Both companies used well-known designers for some of their output, but much of the design work was done by in-house designers, some of whom were secured from the Coalbrookdale School of Art. This was a rare opportunity for women to enter industry as skilled artisans.

Tiles in Everyday Spaces

This area of the museum is superb, recreating some of the real-world contexts in which tiles manufactured were employed. It was great to see the Covent Garden tube station recreation, because that was my tube station for several years when I worked for a company on Long Acre. And if I could have had a glass or two at that wonderful tiled bar, what a great destination that would have been!

Long Gallery

The Long Gallery is elegantly displayed and beautifully designed, showing both sides of individual tiles, and demonstrating the variety of methods and techniques as well as styles and designs manufactured locally. Each of the displays shows a different decorating technique accompanied by tiles, with both front and back display, that illustrate that particular technique or method.

From the Long Gallery to the John Scott Gallery

Between the Long Gallery and the John Scott Gallery is a corridor with views into the historic mould store, and a panel on the corridor wall consisting of more historic moulds. These all have relief patterns that were drawn on and then hand-carved. To make the tile, the clay was pressed or poured into the mould, and then fired. Once it had cooled it could be glazed, before being fired again. The ones stored here are part of the commercial and industrial heritage of Maw and Co and Dunnill Craven and Co.

John Scott Gallery

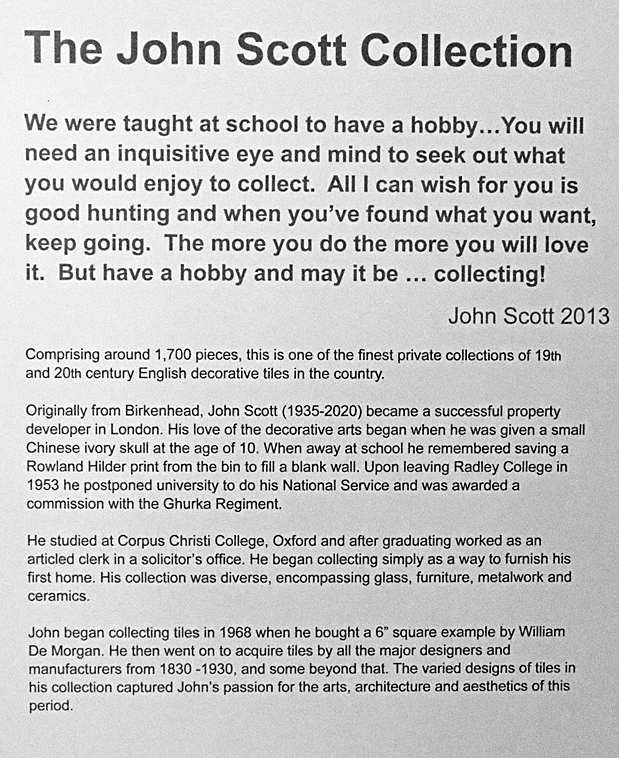

Slightly anomalous, because this is a collection that does not relate specifically to the Ironbridge area, this gallery displays the collection of John Scott, who began collecting tiles in 1968 and continued until he died in 2020. His collection, gifted to the museum in 2013, includes over 1700 pieces, of which an elegant portion are displayed here. I really liked his statement, shown on one of the information panels, that he collected only what he both liked and could afford. He was collecting for his own pleasure, not to build an illustrious collection. By the time he died, his collection had become a remarkable reflection of the history of tile design and manufacturing.

===

Art Nouveau tile panel by John Wadsworth. Minton Works c.1910. The repeat is achieved with just one tile.

Exterior buildings

Once you leave the museum, you will walk out through some of the original buildings that supported the works, including the massive kilns and storage facilities. From here, you can re-enter the museum to visit the gift shop and the cafe before leaving.

When you leave, the church next to the tile-works is well worth a look, with a partially tiled interior.

Final Comments

All of the museums in the immediate Ironbridge area are well thought out and beautifully presented, and I enjoyed them all enormously. The Jackfield Tile Museum was the one that most closely demonstrated domestic and commercial artistic tastes throughout England.

All of the museums in the immediate Ironbridge area are well thought out and beautifully presented, and I enjoyed them all enormously. The Jackfield Tile Museum was the one that most closely demonstrated domestic and commercial artistic tastes throughout England.

The museum offers an impressively detailed insight into multiple aesthetic tastes captured by Victorian tiles and mosaics, showing dozens of them to ensure that visitors are able to appreciate the sheer versatility and exuberance of Victorian taste. Seeing the tiles built into pieces of furniture, and used to create entire spaces like churches, bars, bathrooms and the Covent Garden tube station brought the tiles to life, showing them both as aesthetic decisions and practical architectural applications.

Even though the visual impact of the tiles was always going to steal the show, the museum does not neglect explanations of the really fascinating history of the local tile-works, the development of the manufacturing technologies that went into creating tiles and mosaics, and details about the commercial challenges involved in the marketing and sale of both.

I really loved it.

Visiting

Be careful with the opening days, because when I visited it was closed on Monday and Tuesday, but these days, and the times, change depending on the time of year. If you are intending to visit other museums too, it is worth checking out if they are open at the time of year of your visit. The Broseley clay tobacco pipe works, for example, was closed for the autumn-winter season, which was disappointing. You can find prices and opening times on the museum website here, and if you want to see other museums too there is a page with all the opening times in the related museums here.

Be careful with the opening days, because when I visited it was closed on Monday and Tuesday, but these days, and the times, change depending on the time of year. If you are intending to visit other museums too, it is worth checking out if they are open at the time of year of your visit. The Broseley clay tobacco pipe works, for example, was closed for the autumn-winter season, which was disappointing. You can find prices and opening times on the museum website here, and if you want to see other museums too there is a page with all the opening times in the related museums here.

If you are a member of English Heritage be sure to hand over your card, whether asked for it or not, to obtain a 15% discount.

There’s no guide book, which is a shame.

Jackfield Museum has a car park, which is chargeable via some sort of online arrangement that is loosely described on the website here. I was staying nearby so walked down to the museum and didn’t need to get to grips with the parking system, but I suggest asking at the ticket desk if you have trouble with it.

Nearby there’s an excellent pub called the Black Swan with tables overlooking the Severn outside, and a cosy, friendly interior with excellent pub food. It has a really super, mellow atmosphere and is a two-minute drive away, with plenty of free parking. It has no website but it has a Facebook page and if you Google it, the phone number will come up. It is quite small, so best to book by phone or in person.

==