Hypocaust in the foreground with, in the background, the wall known as the Old Work, making one side of the former basilica.

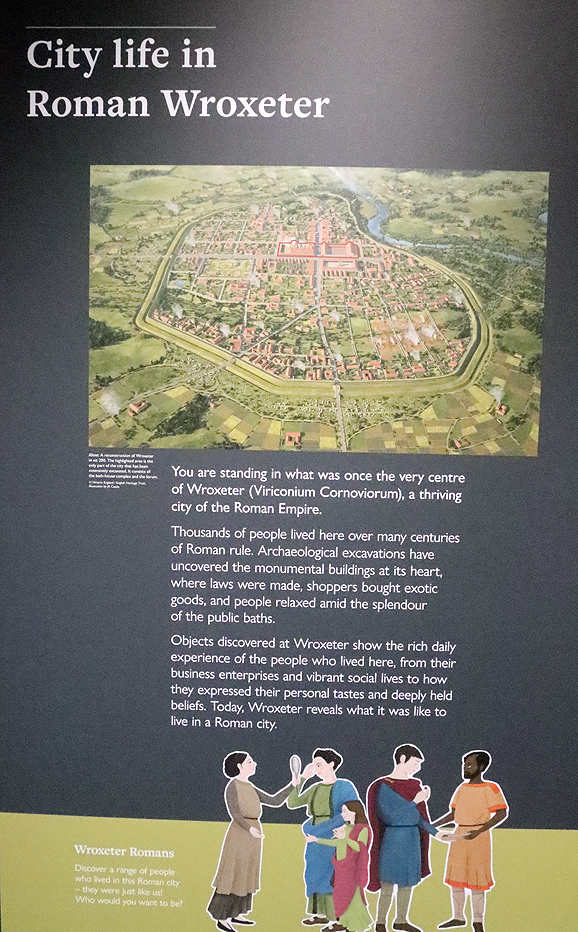

Founded in the mid-1st century AD next to the point of the river Severn where it could be forded, Wroxeter (Viriconium) was built on land farmed by the Iron Age Cornovii. It became a legionary fortress with the capacity to hold 5500 men in the 50s, becoming an urban centre towards the end of the 1st century, eventually becoming Britain’s fourth largest town, four times larger than the the legionary fortress. The remains of the site lie in a rural landscape to the east of Shrewsbury and is managed by Historic England. There is an imaginary reconstruction of a Roman villa. Indoors there is a very nicely presented Visitor Centre with exhibits and displays, as well as a small shop. Visiting details are at the end of this post.

There is little point repeating everything that the fact-filled guide book has to say about Wroxeter and its history, so this is just a short summary of what you can expect to see on a visit.

What remains of the site is a very small section of the original 192 acre (78 hectare) city, consisting of the lowest courses and foundations of the bath-house, part of a market-place and a row of column bases that marks one site of the forum. The road that carries visitors into the town follows the line of the Roman road, Watling Street. The city was surrounded by a 3-mile long circuit of ditches and banks originally topped with a timber palisade, now on farm land and not accessible to the public, but still visible on aerial photographs.

Unlike Chester, York, London and many other Roman urban developments that survived the departure of Rome, Viriconium was one of the Roman towns that were completely abandoned, beginning in the mid-3rd century. Looking out over the surrounding fields towards the Wrekin, after which Viriconium may have been named, it is difficult to imagine a thriving urban mass of public and private buildings connected by a maze of roadways and alleys. A series of archaeological excavations, however, have provided insights into what used to be here, and the visitor centre and guide book do a good job of explaining it.

The town was divided by the mighty Watling Street that connected it to London in the south, and to Whitchurch to the north, where the road forked with one branch going to Chester and the other towards the northeast, York and beyond.

The most conspicuous feature of the site is the single piece of surviving wall, known as the Old Work, shown at the top of this post, which is what remains of what was one of the walls of the basilica, which was shared with the rest of the bath-house. The big opening in the wall marks where there were once double doors. The layers of brick-like stone blocks and tile work were covered in pink plaster, some of which would have been painted with decorative scenes.

Information board showing the main architectural features at the site with the basilica shaded in blue, the shops and marketplace side by side in the foreground and the bath-house taking up the rest of the space.

The bath-house, which has been excavated in its entirety, is the most complete part of the site, with remains of one wall, sections of the the hypocaust (raised heated floor) and the footprint of the baths’ basilica, giving a clear indication of the scale of the original complex. Bath-houses were an important part of Roman life, a component of civilized living and a good place to socialize and network. Even the small industrial base at Prestatyn had a tiny bath-house (posted about here). The Roman visitor to a big bath complex would usually begin in the basilica, a long thin space flanked by columns, where exercise and sports could be carried out in the central area, whilst the side aisles could have been used for personal care activities like massages and hair dressing. At the end of the basilica were two changing rooms.

Then bathers moved through the baths in a sequence from an outdoor cold water plunge pool (heaven help them in this climate!) to an indoor cold water pool (natatio), an unheated room (frigidarium), a warm room (tepidarium), and a number of both wet and dry hot rooms (an alveus, caldarium, and sudatorium). Heat was provided in the warm and hot rooms via a hypocaust, consisting of regularly placed pillars of tiles that once supported a raised floor about 1 metre high, through which hot air was directed from three furnaces. Hollow box-like flue tiles were used to capture the hot air as it rose from below. A piece of decorated ceiling plaster from the hot room has been reconstructed, and copies are kept in both the Visitor Centre and the Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery.

Water from the baths was drained away beneath the bath-house and was used to flush out the latrines, the lower courses of which survive.

Although the rest of the remains today lack the impact of the basilica wall section, mainly consisting of no more than two or three courses of stonework, these too were important parts of the civic quarter of the city, and there are explanatory information boards all over the site that explain what you are looking at and showing helpful artists’ reconstructions of how buildings may have been experienced by the Roman inhabitants.

Next to the bath-house is what remains of a market hall, with two storeys surrounding a central courtyard, containing shops that sold high quality food goods to the wealthy. This building survived into the fifth century AD. Nearby were other shops with open fronts overlooking Watling Street, which may have included food and drink for those using the baths, like modern take-away outlets or bars.

Over the road there is a line of column bases that are the remains of what must have been a very impressive forum, which was once covered 2.5 acres (1 hectare) and measured 80m x 120m (262 x 393ft). This consisted of covered buildings arranged in a square around an open courtyard. The buildings served administrative, legal and mercantile functions, and the ruins represent a colonnade that faced onto Watling Street. The central area was for an open market where stalls could be rented by local traders.

The reconstructed Roman house, a simplified version of excavated building “Site 6,” had a shop facing onto the street with accommodation at the rear. It was built in 2010 for a television programme and provides a good way of visualizing what Watling Street and other areas of Viriconium may have looked like.

Next to the house, but not open to the public, is the model farm built in the mid 19th century by Lord Barnard, and incorporates considerable amounts of Roman stonework in its construction. The farm is no longer in use but is maintained by Historic England.

The visitor centre and the lavishly illustrated guide book provide an excellent overview of the entire city’s history and what was found in archaeological excavations, with more information provided in the Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery.

Visiting

Prices and opening times can be found on the English Heritage website here. There is plenty of parking. The visit begins at the visitor centre, where tickets are purchased and you are given the option of taking an audio guide. I didn’t take one, but plenty of people were using them. There is a small shop where you can purchase a detailed guide book, and although it is impractical to read this as you go around the site, there is a site plan and an aerial photograph with all key features marked, both of which great to have as you walk around. The Visitor Centre is small but excellent, with plenty of helpful information boards and attractive displays of objects found at the site. There is no cafe but there is a picnic area with a few benches.

Prices and opening times can be found on the English Heritage website here. There is plenty of parking. The visit begins at the visitor centre, where tickets are purchased and you are given the option of taking an audio guide. I didn’t take one, but plenty of people were using them. There is a small shop where you can purchase a detailed guide book, and although it is impractical to read this as you go around the site, there is a site plan and an aerial photograph with all key features marked, both of which great to have as you walk around. The Visitor Centre is small but excellent, with plenty of helpful information boards and attractive displays of objects found at the site. There is no cafe but there is a picnic area with a few benches.

The site itself is mostly on the flat, with pathways between all the main buildings and information boards explaining what you are looking at. There was a coach-load of children there at the time I visited and it is clear that for children, the villa was easier to get to grips with than the ruins themselves.

Nearby is St Andrew’s Church, which I very annoyingly missed but is widely recommended with some attractive and unusual features, some dating back to the Norman period. Both the church and the model farm, the latter not open to the public, are described in English Heritage’s Wroxeter guide book.

If you are driving via the A41, both Lilleshall Abbey and Tong’s St Bartholemew’s Church are well worth the visit. Tong is right on the A41, very convenient for a visit en route.

Near to Wroxeter is the 18th century National Trust Attingham Park property. Shrewsbury is not far, and has a really excellent museum and art gallery with a super Roman gallery with finds from Wroxeter. Shrewsbury itself is a lovely and apparently thriving town with a good mixture of architectural styles from the Medieval period onwards, including the vast church of the former Shrewsbury Abbey, some lovely half-timbered buildings and some fine Georgian architecture, as well as some great places to find lunch!

Sources

White, Roger H. 2023. Wroxeter Roman City. English Heritage (also includes St Andrew’s Church, the Victorian model farm and the reconstructed house)

Information displayed in the Wroxeter Visitor Centre

Information displayed in the Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery (Roman gallery)

Discovering Shropshire’s History (website)

Roman Shropshire – (AD 43 – AD 410)

http://www.shropshirehistory.org.uk/html/search/verb/GetRecord/theme:20061122101531

I’ve been thinking about revisiting this place recently, so thanks for whetting my appetite. Also, thanks for clearing up something that was puzzling me. I’d read somewhere about the ceiling mosaic, but couldn’t remember seeing much of a roof there. So it is in fact a reconstruction! That makes much more sense.

LikeLike

Glad that the puzzle is solved Clare! I really did enjoy it. Even knowing one’s way around a basic Roman town plan, there’s enough ambiguity on the ground for the information boards to be needed, and the visitor centre helps too. They have worked really hard to make this understandable as well as physically accessible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was Clare D by the way. Thought i’d logged in🤷🏻♀️. It’s a puzzling world.

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLike