Part 2 – The Neolithic burials in the cave

Introduction

In Part 1 I looked at the excavations carried out at Gop Cave in 1886-7, 1908-14, 1920-21 and 1956-57 and talked about the pre-glacial levels of Gop Cave, with its finds of woolly rhino, hyaena and wild horse, and the Mesolithic tools found outside the cave mouth.

In this second part, the cave is still the topic under discussion, with a shift in focus to the Neolithic layers, whilst the cairn on top of Gop Hill is tackled in part 3. During the Neolithic, the cave was used to deposit a number of burials, two thirds of which were contained within a walled-off section of the cave, and the rest within a narrow passage that linked two parts of the cave. These burials are the subject of this post. References used for all three parts are listed in part 1, together with visiting details.

The Excavations

Modern plan of Gop Cave by Cris Ebbs. Source: Cambrian Caving Council Survey 2013

Just to recap briefly on the details from part 1, the earliest excavations in the cave were carried out by Sir William Boyd Dawkins, a well known and respected early archaeologist who excavated the cave site over two seasons in 1887 and 1887, having originally been asked to assess the cairn on top of the hill. The lowest level was barren , but the next contained numerous bones of Pleistocene animals, many of them now extinct. The top two layers contained mainly Neolithic material including human skeletal remains.

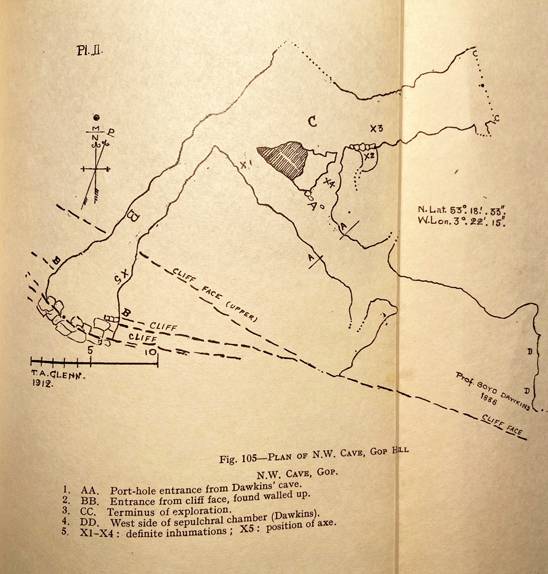

In 1908 John H. Morris began digging at the cave, and was joined by T. Allen Glenn, who took systematic notes and made a plan of the newly uncovered sections of the cave. They opened up a passage missed by Boyd Dawkins, referred to as the northwest passage, which linked to a very small opening just to the east of the main cave entrance. During these excavations a further six partial skeletons were found, two of them children. The skeletal remains in both cases were associated with artefacts and animal bones.

Most of the bone collection collected by Boyd Dawkins, and stored in a pigeon house at Gop Farm, were disposed of in 1913 by the tenant of Gop Farm, who threw them down a local mine shaft – which is particularly sad as Glenn had just received permission to take charge of them. Most of the Morris and Glenn finds, both bones and objects, were sent to the National Museum of Wales. Some finds from Gop Cave are also retained by Manchester Museum and Aura Museum Services, and possibly by the Grosvenor Museum in Chester.

The Neolithic burials at Gop Cave

In total, at least 20 individuals were recorded in Gop Cave. The 14 found by Boyd Dawkins and the 6 found by Morris and Glenn may have been deposited at slightly different times, due to the different character of the deposition. Whereas the individuals discovered by Boyd-Dawkins seem to have been buried whole, Glenn is fairly confident that the ones discovered by himself and Morris in a different part of the cave were only partial when they were interred.

Boyd-Dawkins excavations showing the chamber (feature B) above layer 3 and abutting layer 4, which contained skeletal remains of humans with artefacts. Source: Boyd Dawkins 1901. See other cave plans in part 1.

Dawkins describes how he found a thick layer of charcoal over slabs of limestone at a depth of 4ft (c.1.2m) from the surface, which formed an old hearth. Blackened slabs were found throughout the area excavated, and there were also burnt and broken bones of domestic animals and fragments of pottery. “Intermingled with these were a large quantity of human bones of various ages, lying under slabs of limestone, which formed a continuous packing up to the roof. On removing these a rubble wall became visible, regularly built of courses of limestone.” These limestone blocks made up walls on three sides, with the cave wall itself making up the fourth wall, to form a chamber 4ft 6 by 5ft 4 (c.1.4m x 1.65m). Inside the chamber was what Dawkins describes as “a mass of human skeletons of various ages, more than fourteen in number, closely packed together, and obviously interred at successive times.” Individuals were deposited in a crouched position, “with arms and legs drawn together and folded.” His assessment was that the bodies were buried whole. When the chamber became full, another area of the cave was used as an overflow for new burials, identified on the section plan above as area A. Because layer 3 was found beneath the burial chamber, as well as beneath layer 4, Boyd Dawkins concluded that layer 3 had formed a habitation area prior to the burials, in a similar way to two other cave sites in north Wales.

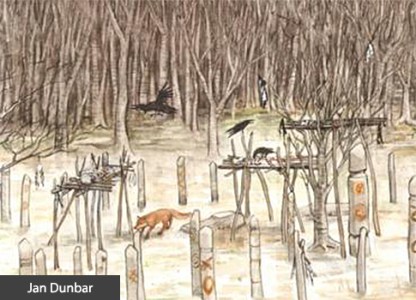

When Morris and Glenn opened up another passage, and found another six individuals, Although the view was confused by rock fall and a very uneven floor, it was thought that limestone slabs may have been used to create a wall around some of the skeletons. Glenn describes the bones as fragmented and partial. Glenn ascribes this to the remains having been brought from somewhere else, rather than having been depleted due to roof fall damage of fragile bones, or the work of the “burrowing animals” that caused disruption in the stratification within the passage. He was methodical and a good observer, so presumably had good grounds for suggesting this, and it is certainly in keeping with other, more recent archaeological evidence for Neolithic burials where partial skeletons are found, apparently due to having died elsewhere and been moved to a particular site for burial. Another possibility is that the body had been excarnated, a practice involving the ceremonial placement of a body in the open air to allow it to be processed naturally so that it was defleshed and partially disarticulated before being collected for interment, which often resulted in the bigger longbones and crania being collected whilst finger and foot bones were left behind.

Having opened the cave out and discovered the second entrance, Morris and Glenn found that it was blocked with limestone slabs, apparently deliberately, although it is by no means certain when this was done. It is not unlike the blocking of entrances to Neolithic burial monuments towards the end of the Neolithic period.

The artefacts associated with the burials

The artefacts associated with both sets of skeletons are all Neolithic in date. Boyd Dawkins assigned them to the Bronze Age on the basis of the pottery, but this has since been re-dated. Both the Boyd Dawkins and the Morris and Glenn excavations produced stone tools, most of which are fairly generic but can be assigned to the Neolithic. One of the Boyd Dawkins discoveries was a long, curved blade, very carefully carved and polished to provide it with smooth surfaces, and showing no signs of usage. He also identified quart pebbles, which he refers to as “luck stones.” Another notable stone tool, this time found by Harris and Glenn in the part of the cave undiscovered by Boyd Dawkins, was a bifacially worked axe head made from Graig Lywyd stone from the well-known Neolithic stone mines at Penmaenmawr, which was apparently unused.

Objects found by Harris and Allen in Gob Cave, including the Graig Lwyd axe at top. Source: Davies 1949.

The pottery was Peterborough ware, and it has been determined that the Gop Cave type was the Mortlake variant of Peterborough ware, which dates to between about 3350 and 2850 BC. All were fragments, and were either grey or black or burnt red.

Pottery found in association with the skeletons by Boyd Dawkins, since identified as Mortlake Ware. Source: Boyd Dawkins 1901

Two unusual items were referred to by Boyd Dawkins as “links,” which he thought were proably used to fasten clothing, and are referred to by some others as belt-sliders. He described them as being made of “jet or Kimmeridge coal,” or “Kimmeridge shale.” As these items are now lost, they cannot be tested (they were last known to be in Manchester Museum, but now cannot be found). He gives the measurements as 54mm L x 22m W and 16mm H; and 70mm L, 22mm W and 27mm H. Boyd Dawkins says that they showed no signs of any usage, and according to Alison Sheriden’s analysis of these object types, this is typical. They appear to have been kept for show rather than being attached to clothing or employed in some other everyday capacity, much like the curved blade and the Graig Lwyd axe head. As jet and Kimmeridge coal come from Yorkshire, and a third of all known sliders have been found in and around Yorkshire, they are certainly exotic goods in northeast Wales, and the rarity of the substance may have endowed it with a particular cachet. Jet has the very unusual property of being electrostatic, so that when it is rubbed it can make one’s hair stand on end! If it was jet, this would certainly have added to its novelty value. 29 of them were known when Sheriden was surveying them in 2012, of which only 6 were certainly of jet, one of which was found in Wales. 12 or 13 were from burial contexts and distribution showed “a marked tendency towards coastal and riverine finds” that are a reminder of the extensive networks that operated in the Neolithic.

Although the objects in the cave are few and far between, some were unused suggesting that they highly valued and retained for special occasions or as prestige items. It is unclear whether any artefacts were associated with any particular individuals, although Boyd-Dawkins describes the the jet sliders and the polished flint flake forming one group together.

Animal remains

Although he does not list numbers, Boyd Dawkins says that the remains of the domesticated species “were greatly in excess of those of the wild animals, and the most abundant were those of sheep.” He also comments that the horse listed under wild fauna may actually be domesticated, and that foxes were using the vicinity of the cave area at the time of the excavation. All bones were found in what he describes as “prehistoric refuse heaps and that nearly all were broken and burnt.

As all the bones were discarded in 1913, none of the identifications can be checked, but Boyd Dawkins was very experienced in the identification of animal remains, giving some confidence that his work reflected the reality of the situation. Sheep and goat are notoriously difficult to tell part, so the question-mark against goat is not surprising. That sheep are dominant is not a surprise, as the area around Gop would be ideal grazing for them. The valley bottom would have been well-suited for cattle and horse.

Dating the skeletons

Although the artefacts found in the cave, loosely associated with the skeletal remains, are indicators of a mid-Neolithic date, as described above, in 2020 Rick Schulting was able to pull together 23 samples from a number of caves for radiocarbon dating, including three samples from Gop Cave, comprising two mandibles and one cranium. Although some samples had been tested previously, an error in the sampling method had led to them being withdrawn in 2007. For Gop, the new dates lie firmly with the Middle-Late Neolithic range, tending towards the middle of the Neolithic (between c.3100 and 2900 BC).

This date range backs up the findings of the Mortlake variants of the Peterborough ware, the jet sliders and the Graig Lwyd axe.

The practice of non-monumental burials

The main form of burial recognized throughout most of the Neolithic Britain is the long barrow or cairn, or the round passage grave. In each case, there was usually an accumulation of burials over time, referred to as collective burials. These were not, however, the only forms of burial during the Neolithic. Although less often found, because of the lack of monumental marker, flat interment cemeteries are known, burials in the ditches of the so-called causewayed enclosures are often recorded and there is some, uncertain data that there may have been burials in rivers. During the later Neolithic, cremation became the norm.

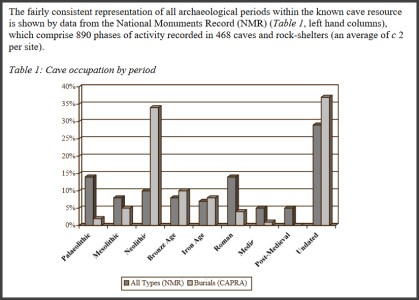

By far the most common non-monumental form of burial, however, is deposition within a cave. Cave burials of various dates are known from all over Britain. In his survey of cave burials in 2020, Rick Schulting noted examples from the Palaeolithic through to the Anglo-Saxon period. From the Neolithic in north Wales, contemporary with Gop Cave, nearby Nanty-Fuach rock shelter above Dyserth produced five burials, all contracted, and without grave goods. Outside the cave there were fragments of Neolithic pottery, a large barbed and tanged arrowhead and, nearby, some Peterborough ware. In the Alyn valley 16 burials were deposited within Perthi Cawarae, and 6 within Rhos Ddigre, the latter associated with a Graig Lwyd axe and pottery fragments, both in the Alyn valley. Other examples are known from Loggerheads and Mostyn with Neolithic flint implements. It is clear that Gop Cave is by no means an isolated example, although the precise arrangement of the skeletal remains within containing walls may be unusual. As many caves were excavated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when excavations lacked today’s precision, it is impossible to know what was missed by excavators. Finally, Schulting notes that there is a gap of “several millennia” between the last Mesolithic cave burial and the first Neolithic ones, indicating that there is no continuity of burial tradition in caves between the two periods.

Meaning in collective burial

Frances Lynch suggests that the use of caves for burial, occurring in many areas at different periods “seems to be a matter of convenience rather than cultural preference” but there are alternative views on the matter. In his book on the materiality of stone – Christopher Tilley does not discuss caves, but he references almost every other aspect of stone as a natural material that becomes objectified by human uses and actions. He comments that social identity requires “specific concrete material points of reference in the form of landscapes, places, artefacts and other persons.” Topographic and other natural features are often used by humans to anchor and fix memory and establish places of meaning in landscapes. Carole Crumley highlights the phenomenological experience of features like caves, mountains and springs, and their role in connecting the mental with the material to create both individual and social identity. In their chapter on the uses of landscape features like caves and springs by the Maya in Mesoamerica, James Brady and Wendy Ashmore describe how caves, eternally damp and dripping water, were connected with the sacred and the ritualization of water. By appropriating and modifying such natural features, people have embedded them with meaning to form bridges between the natural, supernatural and the manufactured, blurring the differences to confer special status on these dark places where the dead might be deposited safely.

Frances Lynch suggests that the use of caves for burial, occurring in many areas at different periods “seems to be a matter of convenience rather than cultural preference” but there are alternative views on the matter. In his book on the materiality of stone – Christopher Tilley does not discuss caves, but he references almost every other aspect of stone as a natural material that becomes objectified by human uses and actions. He comments that social identity requires “specific concrete material points of reference in the form of landscapes, places, artefacts and other persons.” Topographic and other natural features are often used by humans to anchor and fix memory and establish places of meaning in landscapes. Carole Crumley highlights the phenomenological experience of features like caves, mountains and springs, and their role in connecting the mental with the material to create both individual and social identity. In their chapter on the uses of landscape features like caves and springs by the Maya in Mesoamerica, James Brady and Wendy Ashmore describe how caves, eternally damp and dripping water, were connected with the sacred and the ritualization of water. By appropriating and modifying such natural features, people have embedded them with meaning to form bridges between the natural, supernatural and the manufactured, blurring the differences to confer special status on these dark places where the dead might be deposited safely.

Artist’s impression of what an excarnation platform might look like. By Jan Dunbar. Source: BBC

A number of authors have suggested that collective burial of humans, and in particular the mingling of bones rather than maintaining skeletons as delineated individuals, is an indication of the individual being subsumed into a collective identity, privileging the group identity over the authority or status of any one individual. Of course, these collective burials, whether in monument or cave, are representatives of much larger communities, and the criteria used for selecting one person for burial over another are lost. It is possible that in order to transform an individual into a representative of the community, a two-stage process was undertaken whereby an individual is excarnated or buried elsewhere, and then moved to a collective burial site, a transformative process during which the individual member of the community loses their individuality and becomes representative of a communal and ancestral link between the past and the present. With the addition of each new individual to the cemetery, another layer of communal meaning was added to the cave, reinforcing the message that the existing burials already encapsulated.

In the contrast between the brightness of the light-coloured limestone reflecting in the sun, and the darkness of the hidden, secret interior there is a resemblance between the relationship between the visually striking chambered tomb and the sepulchre within. Not forgetting, of course, that there is an enormous cairn on top of the hill, just 43m (141ft) away from the cave, which may in itself have been a marker rather than a grave. The cairn is discussed in part 3.

In the contrast between the brightness of the light-coloured limestone reflecting in the sun, and the darkness of the hidden, secret interior there is a resemblance between the relationship between the visually striking chambered tomb and the sepulchre within. Not forgetting, of course, that there is an enormous cairn on top of the hill, just 43m (141ft) away from the cave, which may in itself have been a marker rather than a grave. The cairn is discussed in part 3.

Final Comments

Gop Cave is often left out of accounts of the Neolithic in Wales, or merely mentioned in passing, which is surprising given both the number of its human occupants and the unusual combination of artefacts found within the cave. Cave burials are given secondary status to monumental constructions, but given the number of them in Wales, it is good to see that they are now being researched as valid contributors to the corpus of knowledge about the Neolithic both in Wales and the rest of Britain.

Graph from Jonathan Last showing the usage of caves at different periods in England (The Archaeology of English Caves and Rock-Shelters: A Strategy Document. Centre for Archaeology Report 2003)

Sources and visiting details are in part 1